Turbo-Folk Music and Cultural Representations of National Identity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

SKALKOTTAS Program 148X21

International Conference Program NOVEMBER 29 TO DECEMBER 1, 2019 Music Library of Greece of the Friends of Music Society at Megaron – the Athens Concert Hall Organised by the Music Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of the Friends of Music Society, Megaron—The Athens Concert Hall, Athens State Orchestra, Greek Composer’s Union, Foundation of Emilios Chourmouzios—Marika Papaioannou, and European University of Cyprus. With the support of the Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Directorate of Modern Cultural Heritage The conference is held under the auspices of the International Musicological Society (IMS) and the Hellenic Musicological Society It is with great pleasure and anticipa- compositional technique. This confer- tion that this conference is taking place ence will give a chance to musicolo- Organizing Committee: Foreword .................................... 3 in the context of “2019 - Skalkottas gists and musicians to present their Thanassis Apostolopoulos Year”. The conference is dedicated to research on Skalkottas and his environ- the life and works of Nikos Skalkottas ment. It is also happening Today, one Alexandros Charkiolakis Schedule .................................... 4 (1904-1949), one of the most important year after the Aimilios Chourmouzios- Titos Gouvelis Greek composers of the twentieth cen- Marika Papaioannou Foundation depos- tury, on the occasion of the 70th anni- ited the composer’s archive at the Music Petros Fragistas Abstracts .................................... 9 versary of his death and the deposition Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of Vera Kriezi of his Archive at the Music Library of The Friends of Music Society to keep Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of The Friends safe, document and make it available for Martin Krithara Biographies ............................. -

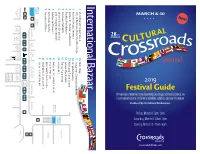

International Bazaar Three Days of Entertainment Featuring Two Stages of Music & Dance, an Three Days of Entertainment Featuring Two 28

S M T USIC A G E MARCH 8-10 free! 28 International Bazaar 1 VL Cultural Productions & 1 0 Tibet Shop City of Bellevue Diversity Advantage 11 Integrated Oriental Medicine 2 Russian Unique Imports 1 2 Simpliful Jewelry 2019 3 Sisters of the Marian Missions 1 3 Alive and Shine Center 4 Pacica Foundation 14 Sahaja Meditation Festival Guide 5 Creature Comforts Trendy Connexion 15 Three days of entertainmentParty City featuring two stages of music & dance, an 6 United States Citizenship Indian Arts 16 and Immigration Services Bed Bath international bazaar, children’s activities, exhibits, and world cuisines A DOLLS OF THE WORLD DISPLAY & Beyond 7 Adefua and Friends Produced by VL Cultural Productions. B CRAFTS FOR KIDS 8 Ann Made Jewelry Hallmark 9 Treasures of Peru C RED CARPET PHOTO AREA D LEGO DISPLAY & PLAYZONE Friday, March 8 · 5pm–9pm D S E LOCAL HISTORY EXHIBIT ANC JoAnn T B Fabrics A G Saturday, March 9 · 10am–9pm E Silver Mini E Creatively Yours A A June Bakery WiggleWorks Dressbarn Palms City Hall Ceramic Studio CSunday, March 10 · 11am–6pm D A E Info 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Hub 12 13 14 15 16 Pier 1 Crossroads Ziti Snip-its Sakkhi Paris Miki Lola Jo’s Tantra Old Navy Ulta Cafe Pasta Kids Style Candy T-Shirts Salon Community Room crossroadsbellevue.com Security SUNDAY MARCH 10 Performance Schedule MUSIC STAGE LOCATED NEAR THE PUBLIC MARKET RESTAURANTS 11:00 – 11:45 Geetanjali Tamil Band Youth Band Performs Tamil Songs FRIDAY MARCH 8 12:00 – 12:45 Dave and the Dalmatians A capella Songs from Croatia, Italy, Corsica & Beyond 12:55 – -

Fabian Stilke, Marketing Director, Universal Music D.O.O

1 Content 2 Foreword – Želimir Babogredac 3 Foreword – Branko Komljenović 4 Next steps 5 Understanding online piracy 7 Record labels in the digital world 8 Croatia Records 9 Menart 10 Dancing Bear 11 Aquarious Records 12 Dallas Records 13 Hit Records 14 Scardona 15 Deezer 16 Online file sharing development 18 Did you know? ABOUT HDU Croatian Phonographic Association (HDU) is a voluntary, non-partisan, non-profit, non-governmental organization which, in accordance with the law, promotes the interests of record labels - phonogram producers, as well as the interests of the Croatian record industry in general. Croatian Phonographic Association was established on 14 June 1995 and was originally founded as an association of individuals dealing with discography and related activities, since at that time this was the only form of association possible under the Law on Associations. Work and affirmation of HDU has manifested mainly in active participation in the implementation of Porin Awards, as well as in various other actions. The HDU is also active with its department for combating piracy that de-lists links from Google, removes pirated content from Web sites and participates in regional initiatives to close the portals that illegally distribute pirated content. Thanks to the successful work, HDU has become an official member of the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) at the beginning of 2007. 2 Foreword Foreword Želimir BabogredacBabogredac, President HDU Branko Komljenović, Vice President HDU The digital era is omnipresent. The Why the first edition of Digital report only work related to the digitization of music now when it is well known that the global experienced a significant upswing, and digital revolution is in full swing in most offer of legal music streaming services world discography markets? and services worldwide increases daily. -

Read the Full Issue

NEW DIVERSITIES An online journal published by the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity Volume 21, No. 1, 2019 New Solidarities: Migration, Mobility, Diaspora, and Ethnic Tolerance in Southeast Europe Guest Editor: Tamara Pavasović Trošt New Solidarities: Migration, Mobility, Diaspora, and Ethnic Tolerance in Southeast Europe 1 by Tamara Pavasović Trošt (University of Ljubljana) Solidarity on the Margins: The Role of Cinema-Related Initiatives in 7 Encouraging Diversity and Inclusivity in Post-1989 Bulgaria by Antonina Anisimovich (Edge Hill University’s Department of Media) Community, Identity and Locality in Bosnia and Herzegovina: 21 Understanding New Cleavages by Marika Djolai (Independent Scholar) In-between Spaces: Dual Citizenship and Placebo Identity at the 37 Triple Border between Serbia, Macedonia and Bulgaria by Mina Hristova (Bulgarian Academy of Science) “Crazy”, or Privileged Enough to Return?: Exploring Voluntary 55 Repatriation to Bosnia and Herzegovina from “the West” by Dragana Kovačević Bielicki Ethnic Solidarities, Networks, and the Diasporic Imaginary: 71 The Case of “Old” and “New” Bosnian Diaspora in the United States by Maja Savić-Bojanić (Sarajevo School of Science and Technology) and Jana Jevtić (Sarajevo School of Science and Technology) Post-war Yugoslavism and Yugonostalgia as Expressions of 87 Multiethnic Solidarity and Tolerance in Bosnia and Herzegovina by Tatjana Takševa (Saint Mary’s University, Canada) Editors: Elena GADJANOVA Julia MARTÍNEZ-ARIÑO Guest Editor: Tamara Pavasović TROŠT Language Editor: Sarah BLANTON Layout and Design: Birgitt SIPPEL Past Issues in 2008-2018: “Contexts of Respectability and Freedom: Sexual Stereotyping in Abu Dhabi”, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018 “The Influence of Ethnic-Specific Networks on Turkish Belgian Women’s Educational and Occupational Mobility”, Vol. -

Introduction Music and Ethnomusicology – Encounters in the Balkans

INTRODUCTION MUSIC AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGY – ENCOUNTERS IN THE BALKANS DANKA LAJIĆ-MIHAJLOVIĆ, JELENA JOVANOVIĆ Abstract: This paper presents an overview of the latest experiences in ethnomusicological research based on the texts incorporated in this col- lection of works. These experiences emanate primarily from the local re- searchers’ works on music of the Balkans, with a heightened theoretical and methodological dimension. The distinctive Balkan musical practices, created through the amalgamation of elements from different cultures, ethnicities, and religions, made this geo-cultural space intriguing not only to researchers from this very region but also to those from other cultural communities. A theoretical framework for interpreting these practices to- gether with the contemporary research methods stem from interactions of local scientific communities’ experiences, sources and practices they deal with, circumstances, ideologies and politics, including the influences of the world’s dominant ethnomusicological communities as well as re- searchers’ individual affinities and choices. A comparison with the re- search strategies applied in similar, transitory geo-cultural spaces contrib- utes to a more complex exploration of the Balkan ethnomusicologists’ experiences. Keywords: the musics of the Balkans, methodologies in ethnomusico- logy, Balkan national ethnomusicologies, fieldwork, interdisciplinarity. Balkan musical practices, as sound images of a geo-cultural space whose distinct identity has been recognized both ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ are incorporated in the perpetual fascination and inspiration of the folklore researchers and eth- nomusicologists. The recognizability that the region has acquired (not only) in ethnomusicology under the term the Balkans,1 along with the motivation of the Balkan scientists to look into its ontology rather than its metaphoric meanings This study appears as an outcome of a research project Identities of Serbian music from a local to global framework: traditions, transitions, challenges, no. -

Final Version

This research has been supported as part of the Popular Music Heritage, Cultural Memory and Cultural Identity (POPID) project by the HERA Joint Research Program (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, DASTI, ETF, FNR, FWF, HAZU, IRCHSS, MHEST, NWO, RANNIS, RCN, VR and The European Community FP7 2007–2013, under ‘the Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities program’. ISBN: 978-90-76665-26-9 Publisher: ERMeCC, Erasmus Research Center for Media, Communication and Culture Printing: Ipskamp Drukkers Cover design: Martijn Koster © 2014 Arno van der Hoeven Popular Music Memories Places and Practices of Popular Music Heritage, Memory and Cultural Identity *** Popmuziekherinneringen Plaatsen en praktijken van popmuziekerfgoed, cultureel geheugen en identiteit Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.A.P Pols and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board The public defense shall be held on Thursday 27 November 2014 at 15.30 hours by Arno Johan Christiaan van der Hoeven born in Ede Doctoral Committee: Promotor: Prof.dr. M.S.S.E. Janssen Other members: Prof.dr. J.F.T.M. van Dijck Prof.dr. S.L. Reijnders Dr. H.J.C.J. Hitters Contents Acknowledgements 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Studying popular music memories 7 2.1 Popular music and identity 7 2.2 Popular music, cultural memory and cultural heritage 11 2.3 The places of popular music and heritage 18 2.4 Research questions, methodological considerations and structure of the dissertation 20 3. The popular music heritage of the Dutch pirates 27 3.1 Introduction 27 3.2 The emergence of pirate radio in the Netherlands 28 3.3 Theory: the narrative constitution of musicalized identities 29 3.4 Background to the study 30 3.5 The dominant narrative of the pirates: playing disregarded genres 31 3.6 Place and identity 35 3.7 The personal and cultural meanings of illegal radio 37 3.8 Memory practices: sharing stories 39 3.9 Conclusions and discussion 42 4. -

Kafana Singers: Popular Music, Gender and Subjectivity in the Cultural Space of Socialist Yugoslavia

Nar. umjet. 47/1, 2010, pp. 141161, A. Hofman, Kafana Singers: Popular Music, Gender Original scienti c paper Received: Dec. 31, 2009 Accepted: March 5, 2010 UDK 78.036 POP:316](497.1)"195/196"(091) 78.036 POP:39](497.1)"195/196"(091) ANA HOFMAN Department for Interdisciplinary Research in Humanities, SRC SASA, Ljubljana KAFANA SINGERS: POPULAR MUSIC, GENDER AND SUBJECTIVITY IN THE CULTURAL SPACE OF SOCIALIST YUGOSLAVIA This article explores the phenomenon of kafana singers in the light of the of cial socialist discourses on popular music and gender during the late 1950s and 1960s in the former Yugoslavia. It seeks to understand how/did the process of estradization along with the socialist gender policy in uence the shift in (self)representation of the female performers in the public realm. By focusing on the dynamic of controversial discourses on folk female singers, the article aims to show how the changes in the of cial discourse helped their profession to become an important resource of their subject actualizations, implicated in the creation of a new sense of social agency. As controversial musical personas, kafana singers personal and professional lives show nuanced interplay between socialist culture policy and its representational strategies. Key words: kafana singers, popular music, socialist culture policy, estradization, gender politics Petar Lukoviþ, a journalist, writes about the folk singer Lepa Lukiþ in his book Bolja prolost: prizori iz muziĀkog ivota Jugoslavije 19401989 [A Better Past: Scenes from Yugoslav Music Life 19401989], making the following observation: In the future feminist debates, Lepa Lukiþ will occupy a special place: before her, women in estrada were more or less objecti ed, primarily treated like disreputable persons. -

Turbofolk Reconsidered

Alexander Praetz und Matthias Thaden – Turbofolk reconsidered Matthias Thaden und Alexander Praetz Turbofolk reconsidered Some thoughts on migration and the appropriation of music in early 1990s Berlin Abstract This paper’s aim is to shed a light on the emergence, meanings and contexts of early 1990s turbofolk. While this music-style has been exhaustively investigated with regard to Yugoslavia and Serbia, its appropriation by Yugoslav labour migrants has hitherto been no subject of particular interest. Departing from this research gap this paper focuses on “Ex-Yugoslav” evening entertainment and music venues in Berlin and the role turbofolk possessed. We hope to contribute to the ongoing research on this music relying on insights we gained from our fieldwork and the interviews conducted in early and mid-2013. After criticizing some suggestions that have been made regarding the construction of group belongings by applying a dichotomous logic with turbofolk representing the supposedly “inferior”, this approach could serve to investigate the interplay between music and the making of everyday social boundaries. Drawing on the gathered interview material we, beyond merely confirming ethnic and national segmentations, suggest the emergence of new actors and the increase of private initiatives and regional solidarity to be of major importance for negotiating belongings. In that regard, turbofolk events – far from being an unambiguous signifier of group loyalty – were indeed capable to serve as a context that bridged both national as well as social cleavages. Introduction The cultural life of migrants from the former Yugoslavia is a subject area that so far has remained to be widely under-researched. -

Traditional Hungarian Romani/Gypsy Dance and Romanian Electronic Pop-Folk Music in Transylvania

Acta Ethnographica Hungarica, 60 (1), pp. 43–51 (2015) DOI: 10.1556/022.2015.60.1.5 TRADITIONAL HUNGARIAN ROMANI/GYPSY DANCE AND ROMANIAN ELECTRONIC POP-FOLK MUSIC IN TRANSYLVANIA Tamás KORZENSZKY Choreomundus Master Programme – International Master in Dance Knowledge, Practice and Heritage Veres Pálné u. 21, H-1053 Budapest, Hungary E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This fi eldwork-based ethnochoreological study focuses on traditional dances of Hungar- ian Romani/Gypsy communities in Transylvania (Romania) practiced to electronic pop-folk music. This kind of musical accompaniment is applied not only to the fashionable Romanian manele, but also to their traditional dances (named csingerálás1, cigányos). Thus Romanian electronic pop-folk music including Romani/Gypsy elements provides the possibility for the survival of Transylvanian Hungarian Romani/ Gypsy dance tradition both at community events and public discoes. The continuity in dance idiom is maintained through changes in musical idiom – a remarkable phenomenon, worthy of further discussion from the point of view of the continuity of cultural tradition. Keywords: csingerálás, pop-folk, Romani/Gypsy, tradition, Transylvania INTRODUCTION This fi eldwork-based ethnochoreological study focuses on traditional dances of a Hungarian Romani/Gypsy2 community at Transylvanian villages (Romania) practiced for Romanian electronic pop-folk music. Besides mahala, manele-style dancing prevailing in Romania in Transylvanian villages, also the traditional Hungarian Romani/Gypsy dance dialect – csingerálás – is practiced (‘fi tted’) for mainstream Romanian pop music, the 1 See ORTUTAY 1977. 2 In this paper, I follow Anca Giurchescu (GIURCHESCU 2011: 1) in using ‘Rom’ as a singular noun, ‘Roms’ as a plural noun, and ‘Romani’ as an adjective. -

In Loving Memory of Milan Yaklich Dennis & Janice Strootman UWM Foundation Non-Profit Slovenian Arts Program Organization 1440 East North Avenue U.S

FALL ISSUE: NOVEMBER 2019 EDITOR: HELEN E. FROHNA NEWSLETTER OF THE UWM SLOVENIAN ARTS COUNCIL SLOVENIAN ARTS PROGRAM How would you describe Slovenian music? President: Christina Carroll Would it be Frankie Yankovic playing his accordion and singing about you and me under the silk umbrella (Židana Marela Polka)? Or would it be the Original Oberkrainer (Ansambel Avsenik) performing Trompetenecho? This is the type of music that most Slovenian-Americans recognize and relate to. When people left their homes and families behind in Slovenia/Austrian Empire to come to America to reinvent their lives in the mines and factories in Michigan’s UP, the Iron Range in Minnesota, and the cities of Cleveland, Chicago, and Milwaukee, they wanted to remember a little bit of “home”. Various singing choirs and musicians organized to replicate the melodies and sounds that they knew when they were growing up. Folk melodies were what they remembered. Over the past 30 years, the UWM Slovenian Arts Council presented various music programs that featured Slovenian performers and/or Slovenian compositions. Not all performers were from Slovenia, not all music sounded like familiar Slovenian folk tunes. Our goal was to showcase various types of music for the enjoyment and enrichment of the Slovenian-American commu- nity and the public at large. Singers and musicians from Slovenia consisted of the Deseti Brat Oktet, Navihanke, Vlado Kreslin, Perpetuum Jazzile, Slovenski Oktet, and the Lojze Slak Ansambel, performing folk, classical, and contemporary compositions. But other programs also featured the Singing Slovenes from Minnesota; from Cleveland, the Jeff Pecon Band, Fantje Na Vasi, and the Fantje’s next generation singers, Mi Smo Mi. -

The Balkans of the Balkans: the Meaning of Autobalkanism in Regional Popular Music

arts Article The Balkans of the Balkans: The Meaning of Autobalkanism in Regional Popular Music Marija Dumni´cVilotijevi´c Institute of Musicology, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] Received: 1 April 2020; Accepted: 1 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: In this article, I discuss the use of the term “Balkan” in the regional popular music. In this context, Balkan popular music is contemporary popular folk music produced in the countries of the Balkans and intended for the Balkan markets (specifically, the people in the Western Balkans and diaspora communities). After the global success of “Balkan music” in the world music scene, this term influenced the cultures in the Balkans itself; however, interestingly, in the Balkans themselves “Balkan music” does not only refer to the musical characteristics of this genre—namely, it can also be applied music that derives from the genre of the “newly-composed folk music”, which is well known in the Western Balkans. The most important legacy of “Balkan” world music is the discourse on Balkan stereotypes, hence this article will reveal new aspects of autobalkanism in music. This research starts from several questions: where is “the Balkans” which is mentioned in these songs actually situated; what is the meaning of the term “Balkan” used for the audience from the Balkans; and, what are musical characteristics of the genre called trepfolk? Special focus will be on the post-Yugoslav market in the twenty-first century, with particular examples in Serbian language (as well as Bosnian and Croatian). Keywords: Balkan; popular folk music; trepfolk; autobalkanism 1.