Turbofolk Reconsidered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk,Narodne,Starogradske Karaoke

060/3471 - 575 061/30 - 560 - 30 [email protected] Списак Folk-narodnih-starogradskih караока на матрицама : 1. Aj berem grožđe – Zorica Brunclik 66.Ja stalno pijem – Đani 124.Nijedne usne se ne ljube same – Džej 184.Sliku tvoju ljubim - Toma Zdravković 2.Aj po gradini (bv) -Čeda Marković 67.Jedan, dva – Džej 125.Nikad nikom nisam reko – Medeni 185.Snijeg pade – Narodna 3.Aj pa pukni zoro – Montevideo 68.Jesen u mom sokaku – Tozovac mesec 186.Splavovi – Novica Zdravković 4.Al nema nas – Nikola Rokvić 69.Još ovu noć – Šaban Šaulić 126.Nikada više -Radmila Manojlović 187.Srce gori jer te voli – S. Armenulić 5.Anonimna – Slobodan Vasić 70.Još uvek slutim -Milan Stanković 127.Niko ne mora da sluša- N. Vojvodić 188.Srce je moje violina – Lepa Lukić 6.Avlije,avlije – Zorica Brunclik 71.Jovano, Jovanke – Makedonska 128.Nikom nije žao kao meni – Džej 189.Srce od silikona -Darko Lazic 7.Beli zora – Marinko Rokvić 72.Kad bi znali kako mi je – Miloš Bojanić 129.Niška banja – Narodna 190.Stani dušo da te ispratim – Ilda 8.Bez tebe je gorko vino - Duško Kuliš 73.Kad ja pođoh aman -Safet Isović 130.Nikom nije žao kao meni – Džej Šaulić 9.Bež Milane -Viki Miljković 74.Kad te ne volim -Katarina Živković 131.Niška banja – Narodna 191.Stani mome da zaigraš – 10.Biljana – Aca Matić 75.Kafana je moja sudbina – Toma 132.Nosim tugu ko okove – G. Božinovska Makedonska 11.Blago meni -Ana Bekuta Zdravković 133.Osvemu mi pričaj ti -Milan Topalović 192.Sto ću čaša polomiti - Crni 12.Blagujno Dejče – Cune Gojković 76.Kako ti je kako živiš – Šaban & Zorica 134.Obeležena – Viki Miljković 193.Sve moje njeno je – Sanja Đorđević 13.Bolje ona nego ja – R. -

The Trombone Sonatas of Richard A. Monaco Viii

3T7? No. THE TROMBONE SONATAS OF RICHARD A. MONACO DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By John A. Seidel, B.S., M.M. Denton, Texas December, 19 88 Seidel, John A., The Trombone Sonatas of Richard A. Monaco, A Lecture Recital, Together with Three Recitals of Selected Works by J.S. Bach, Paul Creston, G.F. Handel, Paul Hindemith, Vincent Persichetti, and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts in Trombone Performance, December, 1988, 43 pp., 24 musical examples, bibliography, 28 titles. This lecture-recital investigated the music of Richard A. Monaco, especially the two sonatas for trombone (1958 and 1985). Monaco (1930-1987) was a composer, trombonist and conductor whose instrumental works are largely unpublished and relatively little known. In the lecture, a fairly extensive biographical chapter is followed by an examination of some of Monaco's early influences, particularly those in the music of Hunter Johnson and Robert Palmer, professors of Monaco's at Cornell University. Later style characteristics are discussed in a chapter which examines the Divertimento for Brass Quintet (1977), the Duo for Trumpet and Piano (1982), and the Second Sonata for Trombone and Piano (1985). The two sonatas for trombone are compared stylistically and for their position of importance in the composer's total output. The program included a performance of both sonatas in their entirety. Tape recordings of all performances submitted as dissertation requirements are on deposit in the library of the University of North Texas. -

Domaće Pesme

SPISAK KARAOKE PESAMA Domaće pesme Sanja - Sindy 064 / 11 55 735 www.facebook.com/SindyKaraoke www.sindykaraoke.com [email protected] DOMAĆE PESME SINDY KARAOKE Sanja 064/11-55-735 najveći izbor domaćih i stranih karaoke pesama (engleskih, italijanskih, francuskih, španskih, ruskih) IZVOĐAČ PESMA IZVOĐAČ PESMA 187 Nikada nećeš znati Aleksandra Radović Ako nikada Aca i Mira Vrati nam se, druže Aleksandra Radović Čuvaj moje srce * Aca Ilić Lepe oči zelene Aleksandra Radović Jesam te pustila Aca Lukas Bele ruže Aleksandra Radović Još danas Aca Lukas Burbon Aleksandra Radović Kao so u moru Aca Lukas Čaše moje polomljene Aleksandra Radović Karta za jug Aca Lukas Dijabolik Aleksandra Radović Nisi moj Aca Lukas Hiljadu puta Aleksandra Radović Zažmuri Aca Lukas Imate li dušu tamburaši Aleksandra Ristanović Dočekaj me sa osmehom Aca Lukas Ista kao ja Alen Islamović Ispod kaputa Aca Lukas Ja živim sam Alen Slavica Dao sam ti dušu Aca Lukas Jagnje moje Alen Vitasović Bura Aca Lukas Koma Alisa Sanja Aca Lukas Kuda idu ljudi kao ja Alka i Džej Da si sada tu Aca Lukas Lična karta Alka i Stavros Zrak, zemlja, zrak Aca Lukas Na žalost Alka i Vuco Kad bi opet Aca Lukas Ne pitaj Alka Vuica Bolje bi ti bilo Aca Lukas Nešto protiv bolova Alka Vuica Ej, šta mi radiš Aca Lukas Niko jedan, dva i tri Alka Vuica Kriva Aca Lukas Otrov sipala Alka Vuica Laži me Aca Lukas Pao sam na dno Alka Vuica Nek’ ti jutro miriše na mene Aca Lukas Pesma od bola Alka Vuica Od kad te nema Aca Lukas Poljem se širi miris tamjana Alka Vuica Profesionalka Aca Lukas Pustinja -

Final Version

This research has been supported as part of the Popular Music Heritage, Cultural Memory and Cultural Identity (POPID) project by the HERA Joint Research Program (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, DASTI, ETF, FNR, FWF, HAZU, IRCHSS, MHEST, NWO, RANNIS, RCN, VR and The European Community FP7 2007–2013, under ‘the Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities program’. ISBN: 978-90-76665-26-9 Publisher: ERMeCC, Erasmus Research Center for Media, Communication and Culture Printing: Ipskamp Drukkers Cover design: Martijn Koster © 2014 Arno van der Hoeven Popular Music Memories Places and Practices of Popular Music Heritage, Memory and Cultural Identity *** Popmuziekherinneringen Plaatsen en praktijken van popmuziekerfgoed, cultureel geheugen en identiteit Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.A.P Pols and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board The public defense shall be held on Thursday 27 November 2014 at 15.30 hours by Arno Johan Christiaan van der Hoeven born in Ede Doctoral Committee: Promotor: Prof.dr. M.S.S.E. Janssen Other members: Prof.dr. J.F.T.M. van Dijck Prof.dr. S.L. Reijnders Dr. H.J.C.J. Hitters Contents Acknowledgements 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Studying popular music memories 7 2.1 Popular music and identity 7 2.2 Popular music, cultural memory and cultural heritage 11 2.3 The places of popular music and heritage 18 2.4 Research questions, methodological considerations and structure of the dissertation 20 3. The popular music heritage of the Dutch pirates 27 3.1 Introduction 27 3.2 The emergence of pirate radio in the Netherlands 28 3.3 Theory: the narrative constitution of musicalized identities 29 3.4 Background to the study 30 3.5 The dominant narrative of the pirates: playing disregarded genres 31 3.6 Place and identity 35 3.7 The personal and cultural meanings of illegal radio 37 3.8 Memory practices: sharing stories 39 3.9 Conclusions and discussion 42 4. -

Pesma Izvođač a Tebe Nema Zorica

PESMA IZVOĐAČ A TEBE NEMA ZORICA BRUNCLIK A U MEĐUVREMENU OK BEND A AJ IMAM TEBE ROĐA RAIČEVIĆ AFRIKA SLAĐA ALLEGRO AJDE JANO NARODNA IZ SRBIJE ALAJ MI JE VEČERAS PO VOLJI NARODNA IZ SRBIJE ALI PAMTIM JOŠ HANKA PALDUM ANDROVERA CIGANSKA ASPIRIN SEKA ALEKSIĆ AUTOGRAM CECA AVLIJE AVLIJE ZORICA BRUNCLIK BATO BRE INDY BY PASS ACA LUKAS BEKRIJA ANA BEKUTA BELE RUŽE ACA LUKAS BELI SE BISERU LEPA BRENA BELLA CIAO GORAN BREGOVIĆ BELO LICE LJUBAM JAS MAKEDONSKA BEOGRAD CECA BIO MI JE DOBAR DRUG MAJA MARIJANA BISENIJA, KĆERI NAJMILIJA CUNE GOJKOVIĆ BITOLA MAKEDONSKA BIO SI MI DRAG INDIRA RADIĆ BLAGUJNO DEJČE SNEŽANA ĐURIŠIC BOGOVI ZEMLJOM HODE LJUBA ALIČIĆ BOŽANSTVENA ŽENO MIROSLAV ILIĆ BUDI BUDI UVIJEK SREĆNA HALID BEŠLIĆ CIGANI LJUBLJAT PESNI CIGANSKA CIGANIMA SRCE DAĆU BOBAN ZDRAVKOVIĆ CIGANINE SVIRAJ SVIRAJ SILVANA ARMENULIĆ CIGANKA SAM MALA STAROGRADSKA CRNE KOSE HANKA PALDUM CRVEN KONAC ANA BEKUTA CRVEN FESIĆ HANKA PALDUM ČAČAK KOLO KOLO ČARŠIJA AL DINO ČIK POGODI LEPA BRENA ČISTO DA ZNAŠ PEĐA MEDENICA ČOKOLADA JAMI ČUVALA ME MAMA LEPA BRENA ČUDNA JADA OD MOSTARA GRADA MEHO PUZIĆ ČUJEŠ SEKO STAROGRADSKA ĆIRIBU ĆIRIBA GARAVI SOKAK DA BUDEMO NOĆAS ZAJEDNO VESNA ZMIJANAC DA MI JE A NIJE DARKO RADOVANOVIĆ DA RASKINEM SA NJOM CECA DA SE NAĐEMO NA POLA PUTA NEDA UKRADEN DA SE OPET RODIM MIRZA I IVANA SELAKOV DA ZNA ZORA STAROGRADSKA DAJTE VINA HOĆU LOM HARIS DŽINOVIĆ DALEKO NEGDE KO ZNA GDE SLAVKO BANJAC DALEKO SI ACA LUKAS I IVANA SELAKOV DANČE TOZOVAC DELIJA MOMAK SINAN SAKIĆ DOBRO JUTRO LEPI MOJ ANA BEKUTA DODIR NEBA NEDELJKO BAJIĆ BAJA DOĐEŠ -

Besplatan Primerak FORSPILKA

Ako želite da naučite ili da se podsetite foršpila poznatih izvođača narodne i folk muzike onda ste na pravom mestu jer tu je FORŠPILKO !! Šta je FORŠPILKO ? FORŠPILKO je priručnik za početnike kao i za profesionalne muzičare u kome se nalaze notirani foršpili (sa trilerima i harmonijom) poznatih izvođača narodne i folk muzike. Zašto morate da imate FORŠPILKA ? Imate sve foršpile na jednom mestu ! Uvek možete da se podsetite neke pesme koju niste dugo svirali ! Ne morate da provodite vreme pored CD-plejera skidajući neku pesmu jer mi smo je već skinuli i notirali za vas ! Što više pesama znate Više ćete i da zaradite na svirkama.Oni koji se profesionalno bave muzikom to dobro znaju ! FORŠPILKA možete da odštampate tako da ga uvek možete nositi sa sobom na svirke ! Sve pesme su po naslovima klasifikovane po abecednom redu radi bržeg snalaženja ! (Sspisak pesama koje se nalaze u FORŠPILKU br. 1 i br. 2) Kupovinom FORŠPILKA postajete član Foršpilko kluba i automatski stičete pravo na raznorazne poklone (naravno u vidu notnih zapisa) FORŠPILA i NOTIRANIH KOLA ! Pogledaj Demo Verziju FORŠPILKA ! FORŠPILKO A F Anđelija - (Milanče Radosavljević) . 1 Fato mori dušmanke - (Aca Matić) . 3 B I Bekrija - (Ana Bekuta) . 1 Ispod palme - (Toma Zdravković) . 3 C J Ciganine ti što sviraš - (Silvana Armenulić) . 2 Ja znam - (Zorica Brunclik) . 4 Č K Čovek sa srca dva - (Šeki Turković) . 2 Ko ostavlja ruže - (Jelena Broćić) . 4 D M Da zna zora - (Safet Isović) . 3 Miljacka - (Halid Bešlić) . 4 1 FORŠPILKO 2 FORŠPILKO 3 4 Spisak pesama koje se nalaze u FORŠPILKU br. 1 (300 Notiranih Foršpila) 1. -

Dolina Naseg Djetinjstva 4

4 ASA - 24 SATA DNEVNO ALEN NIZETIC - NOCAS SE RASTAJU PRIJATELJI 4 ASA - ANA ALEN NIZETIC - OSTANI TU 4 ASA - DA TE NE VOLIM ALEN SLAVICA - DAO SAM TI DUSU 4 ASA - DIGNI ME VISOKO ALEN VITASOVIC - BURA 4 ASA - DOLINA NASEG DJETINJSTVA ALEN VITASOVIC - GUSTI SU GUSTI 4 ASA - EVO NOCI EVO LUDILA ALEN VITASOVIC - JENU NOC 4 ASA - FRATELLO ALEN VITASOVIC - NE MOREN BEZ NJE 4 ASA - HAJDEMO U PLANINE ALISA - SANJA 4 ASA - JA NISAM KOCKAR ALKA VUICA - EJ STA MI RADIS 4 ASA - LEINA ALKA VUICA - LAZI ME 4 ASA - LIPE CVATU ALKA VUICA - NEK TI JUTRO MIRISE NA MENE 4 ASA - NA ZADNJEM SJEDISTU MOGA AUTA ALKA VUICA - OLA OLA E 4 ASA - NAKON SVIH OVIH GODINA ALKA VUICA - OTKAD TE NEMA 4 ASA - NIKOGA NISAM VOLIO TAKO ALKA VUICA - PROFESIONALKA 4 ASA - OTKAZANI LET ALKA VUICA - VARALICA 4 ASA - RUZICA SI BILA AMADEUS - CIJA SI NISI 4 ASA - STA SI U KAVU STAVILA AMADEUS - TAKO MALO 4 ASA - STAVI PRAVU STVAR NA PRAVO AMADEUS BAND - CIJA SI NISI MJESTO AMADEUS BAND - CRNA VATRENA 4 ASA - SVE OVE GODINE AMADEUS BAND - IZNAD KOLENA 4 ASA - TRI ZELJE AMADEUS BAND - KADA ZASPIS 4 ASA - ZA DOBRA STARA VREMENA AMADEUS BAND - LAZU TE ACA LUKAS - BAY PAS AMADEUS BAND - NJU NE ZABORAVLJAM ACA LUKAS - ZAPISITE MI BROJ AMADEUS BAND - RUSKI RULET ACO PEJOVIC - JELENA AMADEUS BAND - SKINI TU HALJINU ACO PEJOVIC - NE DIRAJ MI NOCI AMADEUS BAND - SVE SAM SUZE ACO PEJOVIC - NEMA TE NEMA AMADEUS BAND - TAKVI KAO JA ACO PEJOVIC - NEVERNA AMADEUS BAND - VECERAS ACO PEJOVIC - OPUSTENO AMADEUS BAND - VOLIM JE ACO PEJOVIC - PET MINUTA AMBASADORI - DODJI U 5 DO 5 ACO PEJOVIC - -

Picture This: Musical Imagery

NASHVILLE SYMPHONY YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERTS PICTURE THIS: MUSICAL IMAGERY GRADES 5-8 TABLETABLE OFOF CONTENTSCONTENTS 3 Letter from the Conductor 4 Concert Program 5 Standard Equivalencies 6 Music Resources 7-9 Lesson Plan #1 10-11 Lesson Plan #2 12-13 Lesson Plan #3 14-26 Teacher Resources 27 Pre-Concert Survey 28 Post-Concert Survey 29 Contact Information 30 Sponsor Recognition LETTER FROM THE CONDUCTOR Dear teachers and parents, Welcome to the Nashville Symphony’s Young People’s Concert: Picture Tis! Music has the power to evoke powerful imagery. It has the power to stir our imaginations, express beautiful landscapes, and create thrilling stories. Tis concert will explore images created by some of the world’s greatest composers including Rossini, Grieg, Stravinsky, Prokofev, and Ravel. Te Education and Community Engagement department has put together these lesson plans to help you prepare your students for the concert. We have carefully designed activities and lessons that will coincide with the concepts we will be exploring during the performance. I encourage you to use this guide before or afer the concert to enhance your students’ musical experience. Trough a partnership with NAXOS, we are also able to ofer free online streaming of music that will be featured in the concert. We hope you enjoy! We look forward to seeing you at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center to hear Nashville’s biggest band! Sincerely, Vinay Parameswaran 3 CONCERTCONCERT PROGRAMPROGRAM YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERTS PICTURE THIS: MUSICAL IMAGERY GRADES 5-8 October 20th at 10:15am and 11:45am Concert Program Edvard Grieg | “Morning Mood” from Peer Gynt Suite Gioachino Rossini | “Overture” from Barber of Seville Sergei Prokofev | “Tröika” from Lt. -

Preventeen 47

PREVENTIVE YOUTH MAGAZINE / ISSN 1840 -2461 | DECEMBER 2019 | YEAR XIII | ISSUE 47 Words in the Movement Photography by Denis Smajić | Title of the photography: Autumn Dance of River Una My name is Denis Smajić. I was born on April 1st in 1994 in Bihać where I also live nowadays. For the past eight years I have been periodically doing a photography work, mostly landscape photography. My initial and basic motivation for the photography work is river Una, which is presented in this photo. I took this photo on the river Una canyon somewhere between Bihać and Bosanska Krupa, and in my opinion, that is one of the most beautiful parts of the Una. The river Una is famous for its frequent, bigger or less big, whirlpools, or water vortex, and this year the autumn leaves decided to play with it. The natural, primordial playground filled with countless movements and hidden from curious eyes. Impressum & Table of Contents Jasmila Talić-Kujundžić, MA in Psychology, Saraje vo From Mayakovsky ....................................................................................................31 Tarik Kovač, MA in construction engineering , Vareš Bait ............................................................................................................................... ............3 Amina Mašić, MA in Communicology, Sarajevo You are the father in front of the shop-window ....................33 Jovana Đurić, graduated psychologist , Belgrade Book Fair in Belgrade – the Culture or Kitsch? ..............................4 Emina Sarajlić, BA in English -

Popular Music and Narratives of Identity in Croatia Since 1991

Popular music and narratives of identity in Croatia since 1991 Catherine Baker UCL I, Catherine Baker, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated / the thesis. UMI Number: U592565 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592565 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis employs historical, literary and anthropological methods to show how narratives of identity have been expressed in Croatia since 1991 (when Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia) through popular music and through talking about popular music. Since the beginning of the war in Croatia (1991-95) when the state media stimulated the production of popular music conveying appropriate narratives of national identity, Croatian popular music has been a site for the articulation of explicit national narratives of identity. The practice has continued into the present day, reflecting political and social change in Croatia (e.g. the growth of the war veterans lobby and protests against the Hague Tribunal). -

"Klapa Movement" – Multipart Singing As a Popular Tradition

Nar. umjet. 45/1, 2008, pp. 125-148, J. Ćaleta, The "Klapa Movement" – Multipart Singing... Original scientific paper Received: 17th Jan. 2008 Accepted: 27nd Feb. 2008 UDK 784.4(497.5) JOŠKO ĆALETA Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research, Zagreb THE "KLAPA MOVEMENT" – MULTIPART SINGING AS A POPULAR TRADITION Over the last 30 years, klapa singing, the well-known multipart singing tradition of the coastal and island part of Dalmatia (Southern Croatia), has simply outgrown the local traditional contexts and has become an interesting music phenomenon – a "movement". Over time, the character, music content, and style of the klapa have been dynamically modified, freely adopting new changes; the phenomenon that started as occasional and informal exclusively older male singing transformed into organized, all age, non-gendered singing. Nowadays, this orga- nized form of singing, because of its manner of presentation, is perceived as a style of popular rather than traditional music. The klapa's popularity is a crucial factor for the endurance and development of the klapa multipart singing style. Popularity, in this case, is the recognition of the specific vocal style of a genre within the local or broader community, in which a particular multipart singing style exists. As seems to be common throughout the Mediterranean basin, one of the multipart singing styles became a synonym for the singing of particular region, island or country. Notions such as popularity, modernity, and movement, as well as the klapa movement, klapa community, klapa world, klapa population, klapa scene – terminology that has not had much in common with the purely sonic musical characteristics of multipart singing – helped to explain the present context and status of klapa singing, the traditional multipart singing that ranges from a singing style to the particular musical movement. -

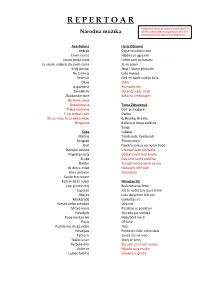

R E P E R T O a R

R E P E R T O A R *Napomena: Pesme označene crvenom bojom ne Narodna muzika sviramo u standardnom programskom delu ali ih možemo odsvirati u dogovoru sa mladencima. Ana Bekuta Haris Džinović Bekrija Dajte vina hoću lom Crven konac Hladno je ugrij me Imam jedan zivot I tebe sam sit kafano Ja nisam rodjena da zivim sama Ja ne pijem Kralj ponoci Jesu l` dunje procvale Ne žalim ja Laže mjesec Veseljak Nek mi bude zadnja čaša Oluja Ođila Uspomene Poznaćeš me Zavoleh te Ostariću neću znati Zlatiborske zore Kako mi nedostaješ Ne živim sama Ostavljena ja Toma Zdravković Treba vremena Da l` je moguce Ti mi trebaš rode Danka Što je moje to je samo moje Ej Branka, Branka Brojanica Kafana je moja sudbina Sanja Ceca Ljiljana Mašina Tamburaši, tamburaši Beograd Pesme moje Brat Navik’o sam ja na noćni život Devojko veštice Umoran sam od života Pogrešan broj Dotak’o sam dno života Bruka Dva smo sveta različita Doktor Svirajte noćas samo za nju Idi dok si mlad Noćas mi srce pati Ime i prezime Tužno leto Kad bi bio ranjen Kažem da te volim Miroslav Ilić Lepi grome moj Božanstvena ženo Lepotan Još te nešto čini izuzetnom Majica Lažu da vreme leči sve Maskarada Luckasta si ti Mesec nebo zvezdice Ova noć Mrtvo more Pozdravi je pozdravi Nevaljala Joj rado joj radmila Popij me kao lek Naljutićeš me ti Poziv Of Jano Pustite me da ga vidim Tebi Nevaljala Polomiću čaše od kristala Tačno je Zoveš me na vino Tražio si sve Smej se smej Turbulentno Šta sam ja u tvom zivotu Volim te Hiljadu suza majko Ljubav fatalna Devojka iz grada Pusti me da raskinem s njom Nije