The Trombone Sonatas of Richard A. Monaco Viii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bassoon Solo List

If you do not see your solo: Solo level request form New Jersey Youth Symphony Solo Audition Requirements 2019-2020 Bassoon Solo List LEVEL ONE 07501 Bach,J.S. Polonaise 07502 Bach,J.S. Bourree I & II (Both) 07503 Bach,J.S./Krane,C. Bach for Bassoon (Any I) 07504 Baines,F. Introduction & Hornpipe 07505 Bakaleinikov,V. Three Pieces (Nos.1&3) 07506 Beethoven,L. Sonatina Anh.5, No. I 07507 Boyce,W./Vedeski,A. Gavotte Symphony No.4 07508 Cacavas,J. Poem 07509 Couperin,F. La Bouffonne 07510 Debussy,C./Paine,H. Sarabande 07511 Duport,J. Romance 07512 Gounod,C./Walters,H. March of a Marionette 07513 Handel Bouree from Fllute Sonata HWY 363b 07514 Haydn,J. Minuet 07515 Haydn,J. Minuet 07516 Lamb,J.(ed.) Classic Festival Solos, Vol.1 07517 Lamb,J.(ed.) Classic Festival Solos, Vol.2 (Either) 07518 Lully,J./Post,S. Gavotte in Rondeau 07519 Marcello,B./Merriman,L. Largo & Allegro 07520 Marcello,B./Merriman,L. Adagio & Allegro 07521 Massenet,J./Johnson,C. Elegy 07522 Paine,H. Scherzo 07523 Pearson,B./ Elledge,M. Standard of Excellence Festival Solos, Bk.2 (Any I) 07524 Pergolesi,G./Barnes,C. Canzona 07525 Pergolesi,G./Elkan,H. Se Tu M'ami. 07526 Phillips,H.(ed.) Eight Bel Canto Songs (Any 2) 07527 Poldini,E./Simpson,W. Poupec Valsante 07528 Ponce,M./Simpson,W. Estrellita 07529 Purcell,H./Dishinger,R. Gavotte and Hornpipe 07530 Purcell,H.Nedeski,A. Gavotte Harpsichord Suite No.5 07531 Rathaus,K. Polichinelle 07532 Ravel,M./Dishinger,R. Pavane pour une infante defunte 07533 Rose,M. -

Turbofolk Reconsidered

Alexander Praetz und Matthias Thaden – Turbofolk reconsidered Matthias Thaden und Alexander Praetz Turbofolk reconsidered Some thoughts on migration and the appropriation of music in early 1990s Berlin Abstract This paper’s aim is to shed a light on the emergence, meanings and contexts of early 1990s turbofolk. While this music-style has been exhaustively investigated with regard to Yugoslavia and Serbia, its appropriation by Yugoslav labour migrants has hitherto been no subject of particular interest. Departing from this research gap this paper focuses on “Ex-Yugoslav” evening entertainment and music venues in Berlin and the role turbofolk possessed. We hope to contribute to the ongoing research on this music relying on insights we gained from our fieldwork and the interviews conducted in early and mid-2013. After criticizing some suggestions that have been made regarding the construction of group belongings by applying a dichotomous logic with turbofolk representing the supposedly “inferior”, this approach could serve to investigate the interplay between music and the making of everyday social boundaries. Drawing on the gathered interview material we, beyond merely confirming ethnic and national segmentations, suggest the emergence of new actors and the increase of private initiatives and regional solidarity to be of major importance for negotiating belongings. In that regard, turbofolk events – far from being an unambiguous signifier of group loyalty – were indeed capable to serve as a context that bridged both national as well as social cleavages. Introduction The cultural life of migrants from the former Yugoslavia is a subject area that so far has remained to be widely under-researched. -

Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2011 Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra Timothy Patrick Cooper [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Timothy Patrick, "Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/964 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Timothy Patrick Cooper entitled "Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Kenneth A. Jacobs, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Brendan P. McConville, Daniel R. Cloutier Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Concerto For Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra A Thesis Presented for the Master of Music Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Timothy Patrick Cooper August 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Timothy Cooper. All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements Several individuals deserve credit for their assistance in this project. -

Senior Recital: Shelby Jones, Bassoon

Kennesaw State University School of Music Senior Recital Shelby Jones, bassoon Benjamin Wadsworth, piano Tuesday, December 8, 2015 5:00 p.m. Music Building Recital Hall Sixty-first Concert of the 2015-16 Concert Season program ALEXANDRE TANSMAN (1897-1986) Sonatine for Bassoon and Piano I. Allegro con moto II. Aria III. Scherzo ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Bassoon Concerto in A minor, RV 497 I. Allegro molto II. Andante molto III. Allegro GYORGY LIGETI (1923-2006) Six Bagatelles for Wind Quintet I. Allegro con spirito II. Rubato. Lamentoso III. Allegro grazioso IV. Presto ruvido V. Adagio. Mesto - Belá Bartók in memoriam VI. Molto vivace. Capriccioso CAMILLE SAINT-SAENS (1835-1921) Bassoon Sonata I. Allegro moderato II. Allegro scherzando CARL MARIA VON WEBER (1786-1826) Andante e Rondo Ungarese This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree Bachelor of Music in Performance. Ms. Jones studies bassoon with Laura Najarian. program notes Sonatine for Bassoon and Piano | Alexandre Tansman Born in Poland, Alexandre Tansman spent most of his musical career in France where he moved after attending school in Poland. He received a degree from the Lodz Conservatory, while he also got his doctoral degree in law from the University of Warsaw. Tansman preferred to call himself a Polish composer, although his music was highly influenced by neoclassical and French composers; two mentors in particular impacted his music indefinitely- Maurice Ravel and Igor Stravinsky. Although Tansman's music was not as popular as most famous composers, his solo piano performances were sought after internationally. Written in 1952, the Sonatine for Bassoon and Piano is a precise example of how his music combines both neoclassical and French elements of music. -

Picture This: Musical Imagery

NASHVILLE SYMPHONY YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERTS PICTURE THIS: MUSICAL IMAGERY GRADES 5-8 TABLETABLE OFOF CONTENTSCONTENTS 3 Letter from the Conductor 4 Concert Program 5 Standard Equivalencies 6 Music Resources 7-9 Lesson Plan #1 10-11 Lesson Plan #2 12-13 Lesson Plan #3 14-26 Teacher Resources 27 Pre-Concert Survey 28 Post-Concert Survey 29 Contact Information 30 Sponsor Recognition LETTER FROM THE CONDUCTOR Dear teachers and parents, Welcome to the Nashville Symphony’s Young People’s Concert: Picture Tis! Music has the power to evoke powerful imagery. It has the power to stir our imaginations, express beautiful landscapes, and create thrilling stories. Tis concert will explore images created by some of the world’s greatest composers including Rossini, Grieg, Stravinsky, Prokofev, and Ravel. Te Education and Community Engagement department has put together these lesson plans to help you prepare your students for the concert. We have carefully designed activities and lessons that will coincide with the concepts we will be exploring during the performance. I encourage you to use this guide before or afer the concert to enhance your students’ musical experience. Trough a partnership with NAXOS, we are also able to ofer free online streaming of music that will be featured in the concert. We hope you enjoy! We look forward to seeing you at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center to hear Nashville’s biggest band! Sincerely, Vinay Parameswaran 3 CONCERTCONCERT PROGRAMPROGRAM YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERTS PICTURE THIS: MUSICAL IMAGERY GRADES 5-8 October 20th at 10:15am and 11:45am Concert Program Edvard Grieg | “Morning Mood” from Peer Gynt Suite Gioachino Rossini | “Overture” from Barber of Seville Sergei Prokofev | “Tröika” from Lt. -

Sonata for Bassoon and Cello in Bb Major K 292 196C Sheet Music

Sonata For Bassoon And Cello In Bb Major K 292 196c Sheet Music Download sonata for bassoon and cello in bb major k 292 196c sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of sonata for bassoon and cello in bb major k 292 196c sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3752 times and last read at 2021-09-29 06:23:06. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of sonata for bassoon and cello in bb major k 292 196c you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Bassoon, Cello Ensemble: Mixed Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Koch Trio Sonata No 1 In D Major Koch Trio Sonata No 1 In D Major sheet music has been read 3510 times. Koch trio sonata no 1 in d major arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 14:41:50. [ Read More ] Quantz Trio Sonata In A Major Qv 2 Anh 32 Quantz Trio Sonata In A Major Qv 2 Anh 32 sheet music has been read 5138 times. Quantz trio sonata in a major qv 2 anh 32 arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 01:32:02. [ Read More ] Koch Trio Sonata No 3 In A Major Koch Trio Sonata No 3 In A Major sheet music has been read 3477 times. -

Chronicling the Developments of the Double Reed

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Honors Theses Student Scholarship Spring 2016 Chronicling the Developments of The oubleD Reed Jenna Sehmann Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Sehmann, Jenna, "Chronicling the Developments of The oubD le Reed" (2016). Honors Theses. 345. https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses/345 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern Kentucky University Chronicling the Developments of The Double Reed Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of HON 420 Spring 2016 By Jenna Sehmann Mentor Dr. Christine Carucci Music Department Abstract Chronicling the Developments of The Double Reed Jenna Sehmann Dr. Christine Carucci, Music Department Abstract Description: This study examines scholarly articles in thirty-eight years of periodical journals, The Double Reed, published by the International Double Reed Society. Research articles were coded to fit into twelve prominent categories: career-related, composition, extended techniques/modern practices, health, historical, instrument, interview, pedagogy, performance practice, performer profile, reeds, and other. After an analysis of journal articles (N =935) from The Double Reed, results indicated historical articles, interviews, and composition-related articles were the most prominent categories. There was a fairly even dispersion between oboe and bassoon articles, while the majority of published material was generated from American authors. Additional trends are noted to inform and advance the double reed community. -

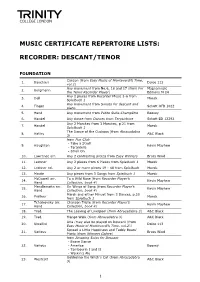

Music Certificate Repertoire Lists: Recorder: Descant

MUSIC CERTIFICATE REPERTOIRE LISTS: RECORDER: DESCANT/TENOR FOUNDATION Canzon (from Easy Music of Monteverdi’s Time, 1. Banchieri Dolce 113 vol.2) Any movement from No.6, 16 and 17 (from For Magnamusic 2. Bergmann the Tenor Recorder Player) Editions M 24 Any 2 pieces from Recorder Music 1-6 from 3. Dell Moeck Spielbuch 1 Any movement from Sonata for descant and 4. Finger Schott OFB 1022 piano 5. Hand Any movement from Petite Suite Champêtre Boosey 6. Handel Any dance from Dances from Terpsichore Schott ED 12292 Any 2 Marches from 3 Marches, p.21 from 7. Handel Moeck Spielbuch 1 The Dance of the Cuckoos (from Abracadabra 8. Hatley A&C Black 3) from Fun Club - Take a Stroll 9. Haughton Kevin Mayhew - Tarantella - Stroll On 10. Lawrence arr. Any 2 contrasting pieces from Easy Winners Brass Wind 11. Lechner Any 2 pieces from 6 Pieces from Spielbuch 1 Moeck 12. Lechner ed. Any 2 or more pieces 19 - 48 from Spielbuch Moeck 13. Maute Any pieces from 3 Songs from Spielbuch 1 Moeck McDowell arr. To a Wild Rose (from Recorder Player’s 14. Kevin Mayhew Hand Collection, book 4) Mendlessohn arr. On Wings of Song (from Recorder Player’s 15. Kevin Mayhew Hand Collection, book 4) March and either Minuet from 3 Dances, p.20 16. Prelleur Moeck from Spielbuch 1 Tchaikovsky arr. Chanson Triste (from Recorder Player’s 17. Kevin Mayhew Hand Collection, book 4) 18. Trad. The Leaving of Liverpool (from Abracadabra 3) A&C Black 19. Trad. Mango Walk (from Abracadabra 3) A&C Black Aria (may also be played on Descant (from 20. -

Catalog of Recent Digital Downloads Spring 2021

Catalog of Recent Digital Downloads Spring 2021 Come, Thou Fount : For SATB and Piano / arr. Eric Nelson [Download]. $1.95 St. Louis: Morning Star Music Publ. ©2018 MSM50-9770 Score - Download http://www.tfront.com/p-498415-come-thou-fount-for-satb-and-piano-arr-eric-nelson.aspx Down In The Valley : For TTBB and Piano / arr. George Mead [Download]. $1.95 Boston: Galaxy Music ©1948 1.1716 Score - Download http://www.tfront.com/p-498417-down-in-the-valley-for-ttbb-and-piano-arr-george-mead.aspx Gratitude and Praise : Organ Music by Jewish-American Composers [Download]. $16.95 Pullman: Harbach Music Publishing ©1994 HMP307 Score; 30 cm.; 28 p. http://www.tfront.com/p-23440-gratitude-and-praise-organ-music-by-jewish-american-composers-[download].aspx Let Us Break Bread Together : For SATB and Piano / arr. Gwyneth Walker [Download]. $2.35 Boston: E.C. Schirmer Music ©2017 8646 Score - Download http://www.tfront.com/p-498419-let-us-break-bread-together-for-satb-and-piano-arr-gwyneth-walker.aspx Organ Music By Women Composers Before 1800 / Edited By Calvert Johnson [Download]. $14.95 Pullman: Harbach Music Publishing ©1993 HMP303 Score; 30 cm.; 20 p. http://www.tfront.com/p-5310-organ-music-by-women-composers-before-1800-edited-by-calvert-johnson.aspx Toccatas and Fugues On Hymns by European Women Composers : For Solo Organ [Download]. $18.95 St. Louis, MO: Harbach Music HMP354 Score; 28 p. Publishing http://www.tfront.com/p-471580-toccatas-and-fugues-on-hymns-by-european-women-composers-for-solo-organ.aspx Tum Balalayke : For SATB A Cappella / arr. -

BULLETIN of the INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL

BULLETIN of the INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL No. XXIII April, 1963 NEWSLETTER AND RADIO NOTES No. 7 INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL 35, PRINCESS COURT, QUEENSWAY, LONDON, W.2 CONTENTS PAGE ZOLTAN K O D A L Y ................................................................................................... 1 M a r iu s B a r b e a u ...................................................................................................2 ZOLTAN KODALY D e a t h s ............................................................................................................................ 2 The following tribute to our President, Professor Dr. Zoltan A nnouncements : Kodaly, was published in Hungarian in a special number of the Sixteenth Annual Conference, Israel....................................... 3 musicological journal Magyar Zene (December, 1962): The Folk Dance Com m ission.................................................3 On behalf of its members throughout the world, the Executive Board of the Directory of Folk Music Organizations 4 International Folk Music Council offers homage to Zoltan Kodaly on his eightieth birthday. We cannot speak for our President, because happily it is I nternational O rganizations : our President whom we are addressing and to whom, through the channel of International Music C o u n c il.................................................5 this journal, we would convey our reverence, affection and gratitude. Inter-American Music Council.................................................5 * * * * International -

Department of Music Programs 2011 - 2012 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet School of Music: Performance Programs Music 2012 Department of Music Programs 2011 - 2012 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, "Department of Music Programs 2011 - 2012" (2012). School of Music: Performance Programs. 45. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog/45 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music: Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of Music 2011-2012 Program s | OLIVET NAZAKENE UNIVERSITY presents Tim Zimmerman a n d th e King’s Brass featuring Ollid Youflfl S' nday, June 5, 2011 Betty and Kenneth Hawkins A Jun. Centennial Chapel A free will offering will be taken. MEMBERS OF THE 2011-2012 KING’S BRASS TOUR | TIM ZIMMERMAN - Director of The King’s Brass, Tim received his graduate degree from the Peabody Conservatory of Music of the Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, Md. He has been a member of the Annapolis Symphony Orchestra and often assists with the Ft. Wayne Philharmonic. For thirteen years, Tim served as artist-in-residence and chairman of the music department at Grace College in Winona Lake, Ind. Presently, he teaches at Indiana Wesleyan University in Marion, Ind. He and his wife, Gina, and their three college-aged children live in Ft. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 28, 2004 I, Eric Stomberg, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Bassoon Performance It is entitled: The Bassoon Sonatas of Victor Bruns: An analytical and performance perspective (with an annotated bibliography of works for bassoon) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: William Winstead Robert Zierolf Mary Sue Morrow The Bassoon Sonatas of Victor Bruns: An analytical and performance perspective (with an annotated bibliography of works for bassoon) A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music May 28, 2004 by Eric Stomberg B.M., University of Kansas, 1994 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1996 Advisor: William Winstead Abstract Sonata repertoire for bassoon and piano is rather narrow in scope and quantity when compared to sonata repertoire of other woodwind instruments. Outside of the sonatas for bassoon and piano of Etler, Hindemith, Hurlstone, Saint-Säens, and Wilder, works are relatively few and rarely played. Representative works from the mid-to-late twentieth century are often difficult even to locate. Fortunately, a substantial body of sonata repertoire lies in the three sonatas for bassoon and piano by Victor Bruns (1904- 96). Bruns was one of many bassoonist-composers, most of whom were professors at the Paris Conservatory, who added to the relatively small amount of repertoire for the instrument, yet his works are relatively unknown.