Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

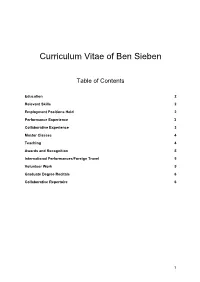

Curriculum Vitae of Ben Sieben

Curriculum Vitae of Ben Sieben Table of Contents Education 2 Relevant Skills 2 Employment Positions Held 2 Performance Experience 3 Collaborative Experience 3 Master Classes 4 Teaching 4 Awards and Recognition 5 International Performances/Foreign Travel 5 Volunteer Work 5 Graduate Degree Recitals 6 Collaborative Repertoire 6 1 BEN SIEBEN [email protected] | 979-479-1197 | 61 San Jacinto St., Bay City, TX, 77414 Education Master of Music in Collaborative Piano 2017 University of Colorado Boulder Primary instructors: Margaret McDonald and Alexandra Nguyen Master of Music in Piano Performance 2012 University of Utah Primary instructor: Heather Conner Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance 2010 Houston Baptist University Primary instructor: Melissa Marse Relevant Skills 25 years of classical piano sight reading improvisation open-score reading transposition jazz and rock styles basso-continuo harpsichord music theory score arranging transcription by ear reading lead sheets keyboard/synthesizer proficiency Italian, German, French, and English diction fluent conversational Spanish Employment Positions Held Emerging Musical Artist-in-Residence, Penn State Altoona 2017 Vocal coach and accompanist for private voice students Graduate Assistant, University of Colorado Boulder 2015-2017 Collaborative pianist, pianist for instrumental students, vocal students, orchestra, opera, and opera scenes classes Choral Accompanist, Texas A&M University 2012-2015 Accompanist for Century Singers and Women’s Chorus Choral Accompanist, Brazos Valley Chorale -

Bassoon Solo List

If you do not see your solo: Solo level request form New Jersey Youth Symphony Solo Audition Requirements 2019-2020 Bassoon Solo List LEVEL ONE 07501 Bach,J.S. Polonaise 07502 Bach,J.S. Bourree I & II (Both) 07503 Bach,J.S./Krane,C. Bach for Bassoon (Any I) 07504 Baines,F. Introduction & Hornpipe 07505 Bakaleinikov,V. Three Pieces (Nos.1&3) 07506 Beethoven,L. Sonatina Anh.5, No. I 07507 Boyce,W./Vedeski,A. Gavotte Symphony No.4 07508 Cacavas,J. Poem 07509 Couperin,F. La Bouffonne 07510 Debussy,C./Paine,H. Sarabande 07511 Duport,J. Romance 07512 Gounod,C./Walters,H. March of a Marionette 07513 Handel Bouree from Fllute Sonata HWY 363b 07514 Haydn,J. Minuet 07515 Haydn,J. Minuet 07516 Lamb,J.(ed.) Classic Festival Solos, Vol.1 07517 Lamb,J.(ed.) Classic Festival Solos, Vol.2 (Either) 07518 Lully,J./Post,S. Gavotte in Rondeau 07519 Marcello,B./Merriman,L. Largo & Allegro 07520 Marcello,B./Merriman,L. Adagio & Allegro 07521 Massenet,J./Johnson,C. Elegy 07522 Paine,H. Scherzo 07523 Pearson,B./ Elledge,M. Standard of Excellence Festival Solos, Bk.2 (Any I) 07524 Pergolesi,G./Barnes,C. Canzona 07525 Pergolesi,G./Elkan,H. Se Tu M'ami. 07526 Phillips,H.(ed.) Eight Bel Canto Songs (Any 2) 07527 Poldini,E./Simpson,W. Poupec Valsante 07528 Ponce,M./Simpson,W. Estrellita 07529 Purcell,H./Dishinger,R. Gavotte and Hornpipe 07530 Purcell,H.Nedeski,A. Gavotte Harpsichord Suite No.5 07531 Rathaus,K. Polichinelle 07532 Ravel,M./Dishinger,R. Pavane pour une infante defunte 07533 Rose,M. -

The Trombone Sonatas of Richard A. Monaco Viii

3T7? No. THE TROMBONE SONATAS OF RICHARD A. MONACO DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By John A. Seidel, B.S., M.M. Denton, Texas December, 19 88 Seidel, John A., The Trombone Sonatas of Richard A. Monaco, A Lecture Recital, Together with Three Recitals of Selected Works by J.S. Bach, Paul Creston, G.F. Handel, Paul Hindemith, Vincent Persichetti, and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts in Trombone Performance, December, 1988, 43 pp., 24 musical examples, bibliography, 28 titles. This lecture-recital investigated the music of Richard A. Monaco, especially the two sonatas for trombone (1958 and 1985). Monaco (1930-1987) was a composer, trombonist and conductor whose instrumental works are largely unpublished and relatively little known. In the lecture, a fairly extensive biographical chapter is followed by an examination of some of Monaco's early influences, particularly those in the music of Hunter Johnson and Robert Palmer, professors of Monaco's at Cornell University. Later style characteristics are discussed in a chapter which examines the Divertimento for Brass Quintet (1977), the Duo for Trumpet and Piano (1982), and the Second Sonata for Trombone and Piano (1985). The two sonatas for trombone are compared stylistically and for their position of importance in the composer's total output. The program included a performance of both sonatas in their entirety. Tape recordings of all performances submitted as dissertation requirements are on deposit in the library of the University of North Texas. -

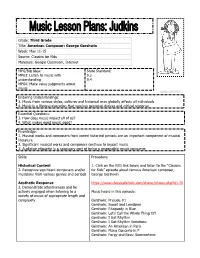

Grade: Third Grade Title: American Composer: George Gershwin Week: May 11-15 Source: Classics for Kids Materials: Google Classroom, Internet

Grade: Third Grade Title: American Composer: George Gershwin Week: May 11-15 Source: Classics for Kids Materials: Google Classroom, Internet MPG/Big Idea: State Standard: MPG3: Listen to music with 9.2 understanding 9.4 MPG4: Make value judgments about music Enduring Understandings: 3. Music from various styles, cultures and historical eras globally affects all individuals 4. Music is a lifelong avocation that requires personal choices and critical response Essential Questions: 3. How does music impact all of us? 4. What makes good music good? Knowledge: 1. Musical works and composers from varied historical periods are an important component of musical literature 3. Significant musical works and composers continue to impact music 3. Audience etiquette is a necessary part of being a responsible music consumer Skills: Procedure: Historical Context 1. Click on the RED link below and listen to the “Classics 2. Recognize significant composers and/or for Kids” episode about famous American composer, musicians from various genres and periods George Gershwin Aesthetic Response https://www.classicsforkids.com/shows/shows.php?id=70 3. Demonstrate attentiveness and be actively engaged when listening to a Music heard in this episode: variety of music of appropriate length and complexity Gershwin: Prelude #1 Gershwin: Sweet and Lowdown Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue Gershwin: Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off Gershwin: I Got Rhythm Gershwin: I Got Rhythm Variations Gershwin: An American in Paris Gershwin: Piano Concerto in F Gershwin: Porgy and Bess: Summertime 2. When finished complete the assignment on the Google Form below Assessment: Answer the multiple-choice questions by using the BLUE link below to open the Google form: https://forms.gle/VMryZf38P3rTPYL8A George Gershwin was born in a. -

EMR 30514 Concerto in F Minor Händel Trombone & Piano

Concerto in F Minor + Trombone ( ) & Piano / Organ Arr.:> Ted Barclay Georg Friedrich Händel EMR 30514 Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter ≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch Concerto in F Minor | Photocopying Georg Friedrich Händel is illegal! (1685 - 1759) original - Concerto for Oboe Arr.: Ted Barclay Grave e = 80 Trombone Organ / Piano f 3 6 mf a piacere mp fp colla parte mp mp 9 cresc. p cresc. p EMR 30514 © COPYRIGHT BY EDITIONS MARC REIFT CH-3963 CRANS-MONTANA (SWITZERLAND) www.reift.ch ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT SECURED 4 12 f 15 A tempo p a piacere ten. p fp colla parte p ten. 18 p p -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

The Trumpet As a Voice of Americana in the Americanist Music of Gershwin, Copland, and Bernstein

THE TRUMPET AS A VOICE OF AMERICANA IN THE AMERICANIST MUSIC OF GERSHWIN, COPLAND, AND BERNSTEIN DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Kriska Bekeny, M.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Professor Charles Waddell _________________________ Dr. Margarita Ophee-Mazo Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The turn of the century in American music was marked by a surge of composers writing music depicting an “American” character, via illustration of American scenes and reflections on Americans’ activities. In an effort to set American music apart from the mature and established European styles, American composers of the twentieth century wrote distinctive music reflecting the unique culture of their country. In particular, the trumpet is a prominent voice in this music. The purpose of this study is to identify the significance of the trumpet in the music of three renowned twentieth-century American composers. This document examines the “compositional” and “conceptual” Americanisms present in the music of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, focusing on the use of the trumpet as a voice depicting the compositional Americanisms of each composer. The versatility of its timbre allows the trumpet to stand out in a variety of contexts: it is heroic during lyrical, expressive passages; brilliant during festive, celebratory sections; and rhythmic during percussive statements. In addition, it is a lead jazz voice in much of this music. As a dominant voice in a variety of instances, the trumpet expresses the American character of each composer’s music. -

Instruments of the Orchestra

INSTRUMENTS OF THE ORCHESTRA String Family WHAT: Wooden, hollow-bodied instruments strung with metal strings across a bridge. WHERE: Find this family in the front of the orchestra and along the right side. HOW: Sound is produced by a vibrating string that is bowed with a bow made of horse tail hair. The air then resonates in the hollow body. Other playing techniques include pizzicato (plucking the strings), col legno (playing with the wooden part of the bow), and double-stopping (bowing two strings at once). WHY: Composers use these instruments for their singing quality and depth of sound. HOW MANY: There are four sizes of stringed instruments: violin, viola, cello and bass. A total of forty-four are used in full orchestras. The string family is the largest family in the orchestra, accounting for over half of the total number of musicians on stage. The string instruments all have carved, hollow, wooden bodies with four strings running from top to bottom. The instruments have basically the same shape but vary in size, from the smaller VIOLINS and VIOLAS, which are played by being held firmly under the chin and either bowed or plucked, to the larger CELLOS and BASSES, which stand on the floor, supported by a long rod called an end pin. The cello is always played in a seated position, while the bass is so large that a musician must stand or sit on a very high stool in order to play it. These stringed instruments developed from an older instrument called the viol, which had six strings. -

A B C a B C D a B C D A

24 go symphonyorchestra chica symphony centerpresent BALL SYMPHONY anne-sophie mutter muti riccardo orchestra symphony chicago 22 september friday, highlight season tchaikovsky mozart 7:00 6:00 Mozart’s fiery undisputed queen ofviolin-playing” ( and Tchaikovsky’s in beloved masterpieces, including Rossini’s followed by Riccardo Muti leading the Chicago SymphonyOrchestra season. Enjoy afestive opento the preconcert 2017/18 reception, proudly presents aprestigious gala evening ofmusic and celebration The Board Women’s ofthe Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Gala package guests will enjoy postconcert dinner and dancing. rossini Suite from Suite 5 No. Concerto Violin to Overture C P s oncert reconcert Reception Turkish The Sleeping Beauty Concerto. The SleepingBeauty William Tell conducto The Times . Anne-Sophie Mutter, “the (Turkish) William Tell , London), performs London), , media sponsor: r violin Overture 10 Concerts 10 Concerts A B C A B 5 Concerts 5 Concerts D E F G H I 8 Concerts 5 Concerts E F G H 5 Concerts 6 Conc. 5 Concerts THU FRI FRI SAT SAT SUN TUE 8:00 1:30 8:00 2017/18 8:00 8:00 3:00 7:30 ABCABCD ABCDAAB Riccardo Muti conductor penderecki The Awakening of Jacob 9/23 9/26 Anne-Sophie Mutter violin tchaikovsky Violin Concerto schumann Symphony No. 2 C A 9/28 9/29 Riccardo Muti conductor rossini Overture to William Tell 10/1 ogonek New Work world premiere, cso commission A • F A bruckner Symphony No. 4 (Romantic) A Alain Altinoglu conductor prokoFIEV Suite from The Love for Three Oranges Sandrine Piau soprano poulenc Gloria Michael Schade tenor gounod Saint Cecilia Mass 10/5 10/6 Andrew Foster-Williams 10/7 C • E B bass-baritone B • G Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe chorus director 10/26 10/27 James Gaffigan conductor bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront James Ehnes violin barber Violin Concerto B • I A rachmaninov Symphonic Dances Sir András Schiff conductor mozart Serenade for Winds in C Minor 11/2 11/3 and piano bartók Divertimento for String Orchestra 11/4 11/5 A • G C bach Keyboard Concerto No. -

Instrument Descriptions

RENAISSANCE INSTRUMENTS Shawm and Bagpipes The shawm is a member of a double reed tradition traceable back to ancient Egypt and prominent in many cultures (the Turkish zurna, Chinese so- na, Javanese sruni, Hindu shehnai). In Europe it was combined with brass instruments to form the principal ensemble of the wind band in the 15th and 16th centuries and gave rise in the 1660’s to the Baroque oboe. The reed of the shawm is manipulated directly by the player’s lips, allowing an extended range. The concept of inserting a reed into an airtight bag above a simple pipe is an old one, used in ancient Sumeria and Greece, and found in almost every culture. The bag acts as a reservoir for air, allowing for continuous sound. Many civic and court wind bands of the 15th and early 16th centuries include listings for bagpipes, but later they became the provenance of peasants, used for dances and festivities. Dulcian The dulcian, or bajón, as it was known in Spain, was developed somewhere in the second quarter of the 16th century, an attempt to create a bass reed instrument with a wide range but without the length of a bass shawm. This was accomplished by drilling a bore that doubled back on itself in the same piece of wood, producing an instrument effectively twice as long as the piece of wood that housed it and resulting in a sweeter and softer sound with greater dynamic flexibility. The dulcian provided the bass for brass and reed ensembles throughout its existence. During the 17th century, it became an important solo and continuo instrument and was played into the early 18th century, alongside the jointed bassoon which eventually displaced it. -

The Source Spectrum of Double-Reed Wood-Wind Instruments

Dept. for Speech, Music and Hearing Quarterly Progress and Status Report The source spectrum of double-reed wood-wind instruments Fransson, F. journal: STL-QPSR volume: 8 number: 1 year: 1967 pages: 025-027 http://www.speech.kth.se/qpsr MUSICAL ACOUSTICS A. THE SOURCE SPECTRUM OF DOUBLE-REED WOOD-VIIND INSTRUMENTS F. Fransson Part 2. The Oboe and the Cor Anglais A synthetic source spectrum for the bassoon was derived in part 1 of the present work (STL-GPSR 4/1966, pp. 35-37). A synthesis of the source spectrum for two other representative members of the double-reed family is now attempted. Two oboes of different bores and one cor anglais were used in this experiment. Oboe No. 1 of the old system without marking, manufactured in Germany, has 13 keys; Oboe No. 2, manufactured in France and marked Gabart, is of the modern system; and the Cor Anglais No. 3 is of the old system with 13 keys and made by Bolland & Wienz in Hannover. Measurements A mean spectrogram for tones within one octave covering a frequen- cy range from 294 to 588 c/s was produced for the oboes by playing two scrics of tones. One serie was d4, e4, f4, g4, and a and the other 4 serie was g 4, a4, b4, c 5' and d5. Both series were blown slurred ascending and descending in rapid succession, recorded and combined to a rather inharmonic duet on one loop. The spectrograms are shown in Fig. 111-A- 1 whcre No. 1 displays the spectrogram for the old sys- tem German oboe and No. -

A Study of Selected Contemporary Compositions for Bassoon by Composers Margi Griebling-Haigh, Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich and Libby

A STUDY OF SELECTED CONTEMPORARY COMPOSITIONS FOR BASSOON BY COMPOSERS MARGI GRIEBLING-HAIGH, ELLEN TAAFFE-ZWILICH AND LIBBY LARSEN by ELIZABETH ROSE PELLEGRINI JENNIFER L. MANN, COMMITTEE CHAIR DON FADER TIMOTHY FEENEY JONATHAN NOFFSINGER THOMAS ROBINSON THEODORE TROST A MANUSCRIPT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the School of Music in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2018 Copyright Elizabeth Rose Pellegrini 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT In my final DMA recital, I performed Sortilège by Margi Griebling-Haigh (1960), Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra by Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich (1939), and Concert Piece by Libby Larsen (1950). For each of these works, I give a brief biography of the composer and history of the piece. I contacted each of these composers and asked if they would provide further information on their compositional process that was not already available online. I received responses from Margie Griebling-Haigh and Libby Larsen and had to research information for Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich. I assess the contribution of these works to the body of bassoon literature, summarize the history of the literature, discuss the first compositions for bassoon by women, and discuss perceptions of the instrument today. I provide a brief analysis of these works to demonstrate how they contribute to the literature. I also offer comments from Nicolasa Kuster, one of the founders of the Meg Quigley Vivaldi Competition. Her thoughts as an expert in this field offer insight into why these works require our ardent advocacy. ii DEDICATION This manuscript is dedicated, first and foremost, to all the women over the years who have inspired me.