Medicinal Plant Fact Sheet: Cypripedium: Lady's Slipper Orchids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cypripedium Candidum Muhl

Cypripedium candidum Muhl. ex Willd. small white lady’s-slipper State Distribution Best Survey Period Photo by Susan R. Crispin Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Status: State threatened clonal clumps. This relatively small lady’s-slipper averages about 20 cm in height, each stem producing several Global and state rank: G4/S2 strongly-ribbed, sheathing leaves that are densely short-hairy. Stems are usually terminated by a single Other common names: white lady-slipper flower (occasionally there may be two) characterized Family: Orchidaceae (orchid family) by its ivory-white pouch (the lip or lower petal) which may be faintly streaked with purple veins toward the Total range: This principally upper Midwestern species bottom and slightly purple-spotted around the pouch ranges eastward to New Jersey and New York, extending opening. The lateral petals, which are similar to the west through southern Michigan to Minnesota, the eastern sepals, are pale yellow-green and spirally twisted. Dakotas, and southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan. To the Cypripedium candidum is known to hybridize with two south it ranges to Nebraska, Missouri, and Kentucky. It is well-known varieties of yellow lady’s-slipper, C. calceolus considered rare in Iowa (S1), Illinois (S3), Indiana (S2), var. pubescens and C. calceolus var. parviflora, producing Kentucky (S1), Michigan (S2), Minnesota (S3), North C. Xfavillianum and C. Xandrewsii, respectively. These Dakota (S2S3), New York (S1), Ohio (S1), South Dakota hybrids are the only taxa that small white lady-slipper is (S1), Wisconsin, and Manitoba. In Pennsylvania and likely to be confused with. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

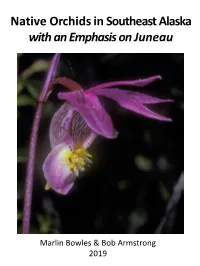

Native Orchids in Southeast Alaska with an Emphasis on Juneau

Native Orchids in Southeast Alaska with an Emphasis on Juneau Marlin Bowles & Bob Armstrong 2019 Acknowledgements We are grateful to numerous people and agencies who provided essential assistance with this project. Carole Baker, Gilbette Blais, Kathy Hocker, John Hudson, Jenny McBride and Chris Miller helped locate and study many elusive species. Pam Bergeson, Ron Hanko, & Kris Larson for use of their photos. Ellen Carrlee provided access to the Juneau Botanical Club herbarium at the Alaska State Museum. The U.S. Forest Service Forestry Sciences Research Station at Juneau also provided access to its herbarium, and Glacier Bay National Park provided data on plant collections in its herbarium. Merrill Jensen assisted with plant resources at the Jensen-Olson Arboretum. Don Kurz, Jenny McBride, Lisa Wallace, and Mary Willson reviewed and vastly improved earlier versions of this book. About the Authors Marlin Bowles lives in Juneau, AK. He is a retired plant conservation biologist, formerly with the Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL. He has studied the distribution, ecology and reproductionof grassland orchids. Bob Armstrong has authored and co-authored several books about nature in Alaska. This book and many others are available for free as PDFs at https://www.naturebob.com He has worked in Alaska as a biologist, research supervisor and associate professor since 1960. Table of Contents Page The southeast Alaska archipellago . 1 The orchid plant family . 2 Characteristics of orchids . 3 Floral anatomy . 4 Sources of orchid information . 5 Orchid species groups . 6 Orchid habitats . Fairy Slippers . 9 Eastern - Calypso bulbosa var. americana Western - Calypso bulbosa var. occidentalis Lady’s Slippers . -

Thuja Occidentalis) Swamps in Northern New York: Effects and Interactions of Multiple Variables

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-16-2017 Plant Species Richness and Diversity of Northern White-Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) Swamps in Northern New York: Effects and Interactions of Multiple Variables Robert Smith SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds Recommended Citation Smith, Robert, "Plant Species Richness and Diversity of Northern White-Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) Swamps in Northern New York: Effects and Interactions of Multiple Variables" (2017). Dissertations and Theses. 7. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds/7 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PLANT SPECIES RICHNESS AND DIVERSITY OF NORTHERN WHITE-CEDAR (Thuja occidentalis) SWAMPS IN NORTHERN NEW YORK: EFFECTS AND INTERACTIONS OF MULTIPLE VARIABLES by Robert L. Smith II A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Syracuse, New York November 2017 Department of Environmental and Forest Biology Approved by: Donald J. Leopold, Major Professor René H. Germain, Chair, Examining Committee Donald J. Leopold, Department Chair S. Scott Shannon, Dean, The Graduate School ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Donald J. Leopold, for his great advice during our many meetings and email exchanges. In addition, his visit to my study site and recommended improvements to my thesis were very much appreciated. -

Germination in the Cypripedium/Paphiopedilum Alliance

Germination in the Cypripedium/Paphiopedilum Alliance The colourful temperate ladyslippers including Cypripedium acaule, calceolus and reginae have attracted the attention of many investigators attempting to solve the problem of germinating the recalcitrant seeds (Arditti, 1967; Arditti et al, 1982; Curtis, 1942; Oliva and Arditti, 1984; Stoutamire, 1974, 1983; Withner, 1953). Germination of Cyp. reginae seed has perhaps attracted the most attention given that this species is particularly showy. Harvais (1973, 1974, 1980, and 1982) was the first Canadian investigator to approach the problem of axenic culture. He succeeded not only in germinating the seeds of Cyp. reginae but also in producing leafy seedlings. His death in 1982 cut short a promising research program and was a great loss. Frosch (1986) outlined a procedure to asymbiotically germinate and grow Cyp. reginae to flower in three years. More recently, Ballard (1987), has presented detailed results of his experiments in the sterile propagation of the same species, using seeds taken at early stages of development and at maturity. Of particular interest was his discovery that dormancy in Cyp. reginae seeds can be broken by refrigeration of the seeds at 5/C for two to three months prior to incubation at room temperature. He has achieved from 19–98% germination after three to four months using Knudson's “C” medium (Knudson, 1946) with seed taken 42 to 60 days after pollination. Cypripedium calceolus is a particularly attractive species, native to both North America and Europe. Carlson (1940) examined the formation of the seed of Cyp. parviflorum to gain a better understanding of the problems involved in germination. -

On the Fringe Journal of the Native Plant Society of Northeastern Ohio

On The Fringe Journal of the Native Plant Society of Northeastern Ohio ANNUAL DINNER Friday, October 22 2004 At the Cleveland Museum of Natural History Socializing and dinner: 5:30 Lecture by Dr. Kathryn Kennedy at 7:30 “Twenty Years of Recovering America’s Vanishing Flora” This speaker is co-sponsored by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History Explorer Series. Tickets: Dinner and lecture: $20.00. Send checks to Ann Malmquist, 6 Louise Drive., Chagrin Falls, OH 44022; 440-338-6622 Tickets for the lecture only: $8.00, purchased through the Museum TICKETS ARE LIMITED, SO MAKE YOUR RESERVATIONS EARLY Annual Dinner Speaker Mark your calendars now! Come and enjoy hearing Dr. Kathryn Kennedy, President of the Center for about the detective work that goes into finding and Plant Conservation, will speak at the Annual Dinner on identifying rare plants and the exciting experimentation Twenty Years of Recovering America’s Vanishing of reproducing them for posterity. Remember: Flora. Extinction is forever. The CPC was begun because our native plants are declining at an alarming rate. Among them are some of Ohio Botanical Garden the most beautiful and useful species on earth. The On July 12th Jane Rogers and I were privileged to be implications of this trend are stunning. The importance guests of Ohio’s First Lady, Hope Taft, at the of plants to life on Earth is immeasurable. The Governor’s Residence in Columbus. Mrs. Taft, an landscapes we cherish, the food we eat, even the very NPSNEO member, was giving us a guided tour of the air we breathe is connected to plant life. -

Willi Orchids

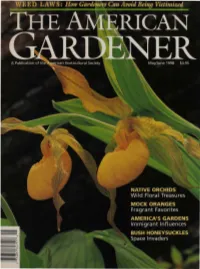

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

Extrapolating Demography with Climate, Proximity and Phylogeny: Approach with Caution

! ∀#∀#∃ %& ∋(∀∀!∃ ∀)∗+∋ ,+−, ./ ∃ ∋∃ 0∋∀ /∋0 0 ∃0 . ∃0 1##23%−34 ∃−5 6 Extrapolating demography with climate, proximity and phylogeny: approach with caution Shaun R. Coutts1,2,3, Roberto Salguero-Gómez1,2,3,4, Anna M. Csergő3, Yvonne M. Buckley1,3 October 31, 2016 1. School of Biological Sciences. Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science. The University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia. 2. Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Western Bank, Sheffield, UK. 3. School of Natural Sciences, Zoology, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland. 4. Evolutionary Demography Laboratory. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. Rostock, DE-18057, Germany. Keywords: COMPADRE Plant Matrix Database, comparative demography, damping ratio, elasticity, matrix population model, phylogenetic analysis, population growth rate (λ), spatially lagged models Author statement: SRC developed the initial concept, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RSG helped develop the initial concept, provided code for deriving de- mographic metrics and phylogenetic analysis, and provided the matrix selection criteria. YMB helped develop the initial concept and advised on analysis. All authors made substantial contributions to editing the manuscript and further refining ideas and interpretations. 1 Distance and ancestry predict demography 2 ABSTRACT Plant population responses are key to understanding the effects of threats such as climate change and invasions. However, we lack demographic data for most species, and the data we have are often geographically aggregated. We determined to what extent existing data can be extrapolated to predict pop- ulation performance across larger sets of species and spatial areas. We used 550 matrix models, across 210 species, sourced from the COMPADRE Plant Matrix Database, to model how climate, geographic proximity and phylogeny predicted population performance. -

Review of Selected Species Subject to Long- Standing Import Suspensions

UNEP-WCMC technical report Review of selected species subject to long- standing import suspensions Part II: Asia and Oceania (Version edited for public release) Review of selected species subject to long-standing import suspensions. Part II: Asia and Oceania Prepared for The European Commission, Directorate General Environment, Directorate E - Global & Regional Challenges, LIFE ENV.E.2. – Global Sustainability, Trade & Multilateral Agreements, Brussels, Belgium Prepared February 2016 Copyright European Commission 2016 Citation UNEP-WCMC. 2016. Review of selected species subject to long-standing import suspensions. Part II: Asia and Oceania. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge. The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) is the specialist biodiversity assessment of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organization. The Centre has been in operation for over 30 years, combining scientific research with policy advice and the development of decision tools. We are able to provide objective, scientifically rigorous products and services to help decision- makers recognize the value of biodiversity and apply this knowledge to all that they do. To do this, we collate and verify data on biodiversity and ecosystem services that we analyze and interpret in comprehensive assessments, making the results available in appropriate forms for national and international level decision-makers and businesses. To ensure that our work is both sustainable and equitable we seek to build the capacity of partners -

Orchids of Lakeland

a field guide to OrchidsLakeland Provincial Park, Provincial Recreation Area and surrounding region Written by: Patsy Cotterill Illustrated by: John Maywood Pub No: I/681 ISBN: 0-7785-0020-9 Printed 1998 Sepal Sepal Petal Petal Seed Sepal Lip (labellum) Ovary Finding an elusive (capsule) orchid nestled away in Sepal the boreal forest is a Scape thrilling experience for amateur and Petal experienced naturalists alike. This type Petal of recreation has become a passion for Column some and, for many others, a wonder- ful way to explore nature and learn Ovary Sepal (capsule) more about the living world around us. Sepal But, we also need to be careful when Lip (labellum) looking at these delicate plants. Be mindful of their fragile nature... keep Spur only memories and take only photo- graphs so that others, too, can enjoy. Corm OrchidsMany people are surprisedin Alberta to learn that orchids grow naturally in Alberta. Orchids are typically associated with tropical rain forests (where indeed, many do grow) or flower-shop purchases for special occasions, exotic, expensive and highly ornamental. Wild orchids in fact are found world-wide (except in Antarctica). They constitute Roots Tuber the second largest family of flowering plants (the Orchidaceae) after the Aster family, with upwards of 15,000 species. In Alberta, there are 26 native species. Like all Roots orchids from north temperate regions, these are terrestrial. They grow in the ground, in contrast to the majority of rain forest species which are epiphytes, that is, they grow attached to trees for support but do not derive nourishment from them. -

Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society of London

I 3 2044 105 172"381 : JOURNAL OF THE llopl lortimltoal fbck EDITED BY Key. GEORGE HEXSLOW, ALA., E.L.S., F.G.S. rtanical Demonstrator, and Secretary to the Scientific Committee of the Royal Horticultural Society. VOLUME VI Gray Herbarium Harvard University LOXD N II. WEEDE & Co., PRINTERS, BEOMPTON. ' 1 8 8 0. HARVARD UNIVERSITY HERBARIUM. THE GIFT 0F f 4a Ziiau7- m 3 2044 i"05 172 38" J O U E N A L OF THE EDITED BY Eev. GEOEGE HENSLOW, M.A., F.L.S., F.G.S. Botanical Demonstrator, and Secretary to the Scientific Committee of the Royal Horticultural Society. YOLUME "VI. LONDON: H. WEEDE & Co., PRINTERS, BROMPTON, 1 8 80, OOUITOIL OF THE ROYAL HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY. 1 8 8 0. Patron. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN. President. The Eight Honourable Lord Aberdare. Vice- Presidents. Lord Alfred S. Churchill. Arthur Grote, Esq., F.L.S. Sir Trevor Lawrence, Bt., M.P. H. J". Elwes, Esq. Treasurer. Henry "W ebb, Esq., Secretary. Eobert Hogg, Esq., LL.D., F.L.S. Members of Council. G. T. Clarke, Esq. W. Haughton, Esq. Colonel R. Tretor Clarke. Major F. Mason. The Rev. H. Harpur Crewe. Sir Henry Scudamore J. Denny, Esq., M.D. Stanhope, Bart. Sir Charles "W. Strickland, Bart. Auditors. R. A. Aspinall, Esq. John Lee, Esq. James F. West, Esq. Assistant Secretary. Samuel Jennings, Esq., F.L S. Chief Clerk J. Douglas Dick. Bankers. London and County Bank, High Street, Kensington, W. Garden Superintendent. A. F. Barron. iv ROYAL HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY. SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE, 1880. Chairman. Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, K.C.S.I., M.D., C.B.,F.R.S., V.P.L.S., Royal Gardens, Kew. -

The General Status of Alberta Wild Species 2000 | I Preface

Pub No. I/023 ISBN No. 0-7785-1794-2 (Printed Edition) ISBN No. 0-7785-1821-3 (On-line Edition) For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre – Publications Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 - 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 - 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-3362 OR Visit our website at www.gov.ab.ca/env/fw/status/index.html (available on-line Fall 2001) Front Cover Photo Credits: OSTRICH FERN - Carroll Perkins | NORTHERN LEOPARD FROG - Wayne Lynch | NORTHERN SAW-WHET OWL - Gordon Court | YELLOW LADY’S-SLIPPER - Wayne Lynch | BRONZE COPPER - Carroll Perkins | AMERICAN BISON - Gordon Court | WESTERN PAINTED TURTLE - Gordon Court | NORTHERN PIKE - Wayne Lynch ASPEN | gordon court prefacepreface Alberta has long enjoyed the legacy of abundant wild species. These same species are important environmental indicators. Their populations reflect the health and diversity of the environment. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development The preparation and distribution of this report is has designated as one of its core business designed to achieve four objectives: goals the promotion of fish and wildlife conservation. The status of wild species is 1. To provide information on, and raise one of the performance measures against awareness of, the current status of wild which the department determines the species in Alberta; effectiveness of its policies and service 2. To stimulate broad public input in more delivery. clearly defining the status of individual Central to achieving this goal is the accurate species; determination of the general status of wild 3.