Mapping Equitable Availability of Open Space in Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Appraisal

Serial No.: N86 Historic Building Appraisal Old Quarry Site Structures Lei Yue Mun, Kwun Tong, Kowloon Hong Kong has been well favoured with its building stones. The high quality, Historical fine-grained granite was commonly used in construction by the time the island of Interest Hong Kong was taken over by the British in 1841. This situation continued after the British arrival, with quarries stretching along the northern coastline of the Island, ranging from Shek Tong Tsui (䞛⠀) in the western part to Quarry Bay (殪欂㴴) and A Kung Ngan (旧℔ⱑ) in the east. There were many new colonial buildings and structures which, at this date, were rich in local granite. Surviving examples include Flagstaff House and St John’s Cathedral. The general topography of the villages of Lei Yue Mun (歱欂攨), Ngau Tau Kok (䈃柕奺), Sai Cho Wan (勄勱䀋) and Cha Kwo Ling (勞㝄ⵢ) in Kowloon was quite hilly, offering little arable land for crop growing, but they were rich in granite. They were well known for the production of stones, and thus got the name of ‘Si Shan’ (⚃Ⱉ, ‘Four Hills’). The Qing government appointed a ‘Tau Yan’ (柕Ṣ) (headman) in each of the ‘Four Hills’ to manage the quarries. There was a ‘Sze Shan Kung So’ (⚃Ⱉ℔, Communal Hall of Four Hills) to discuss matters relating to stone business. The famous Canton Cathedral (⺋ⶆ䞛⭌) was built with granite cut in the “Four Hills”. The British takeover of Kowloon and the New Territories led to a greater demand of stone for construction. At the time, the more prominent stone-cutting stores in Lei Yue Mun included Tung Li Tong (⎴⇑➪) owned by Ip Wa-shing (叱厗⊅) (1844-1914), Tung Tai Tong (⎴㲘➪) owned by Tsang Lam-on (㚦㜿 ⬱) and Tung Fuk Tong (⎴䤷➪) owned by Ip Fuk (叱䤷). -

LC Paper No. CB(1)531/20-21(05)

LC Paper No. CB(1)531/20-21(05) For discussion on 23 February 2021 Legislative Council Panel on Development Progress of Work by the Sustainable Lantau Office (SLO), and Staffing Proposals of SLO, Planning Department and Railway Development Office of Highways Department for Taking Forward and Implementation of Development and Conservation Projects related to Lantau PURPOSE The paper aims to brief members on: (a) the proposal of the Sustainable Lantau Office (SLO) of the Civil Engineering and Development Department (CEDD) to retain four supernumerary directorate posts, and create two supernumerary directorate posts up to 31 March 2025 to provide directorate support for the implementation of new and on-going development and conservation initiatives in Lantau (details at Enclosure 1); (b) the proposal of the Planning Department to create one supernumerary directorate post of Chief Town Planner up to 31 March 2025 to provide high-level steer for various strategic planning tasks for the sustainable development of Lantau (details at Enclosure 2); (c) the proposal of the Railway Development Office of the Highways Department to create one supernumerary directorate post of Chief Engineer up to 31 March 2025 to provide technical support for the planning and implementation of the proposed priority rail links and the possible rail links for the longer term under the “Studies related to Artificial Islands in the Central Waters” (details at Enclosure 3); and (d) the progress of work made by SLO of CEDD (details at Enclosure 4). ADVICE SOUGHT 2. Members are invited to comment on the above staffing proposals1. After soliciting Members’ comments, we intend to submit the proposals to the Establishment Subcommittee for consideration and to the Finance Committee for approval at the soonest opportunity. -

3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 3.1 Scope of the Project 3.2 South Apron

3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 3.1 Scope of the Project 3.1.1.1 Further to the recommendations of the Option Assessment and subsequent alignment developments detailed in Section 2 of this report, the preferred Trunk Road T2 is shown in Figure 3.1 and will comprise: • a dual two-lane trunk road of approximately 3.0km long with about 2.7km of the trunk road in form of tunnel; • ventilation and administration buildings and a traffic control and surveillance system; and • associated civil, electrical, mechanical, landscaping and environmental protection and mitigation works. 3.1.1.2 The works for the Trunk Road T2 project are grouped under the following major geographical headings: a) The South Apron Section – all works for the Trunk Road T2 Project located at the South Apron of the former Kai Tak Airport, including a ventilation building, a section of at-grade road, a section of depressed road, a section of cut and cover tunnel, a vertical launching shaft for the tunnel boring machines (TBM), a section of twin TBM tunnel and ancillary works. b) The Subsea Tunnel Section – all works for the Trunk Road T2 project in the sea between the South Apron and Cha Kwo Ling, including twin subsea TBM tunnels. c) The Cha Kwo Ling Section – all works for the Trunk Road T2 project located at the former Cha Kwo Ling Public Cargo Works Area (PCWA), including a section of cut and cover tunnel, a vertical receiving shaft for the TBMs, a section of twin TBM tunnels, a ventilation building and an administration building located inside the Lam Tin Interchange. -

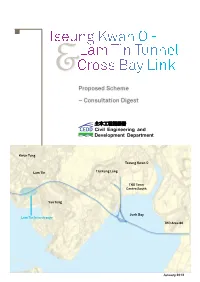

Tseung Kwan O - 及 Lam Tin Tunnel Cross Bay Link

Tseung Kwan O - 及 Lam Tin Tunnel Cross Bay Link Proposed Scheme – Consultation Digest Kwun Tong Tseung Kwan O Lam Tin Tiu Keng Leng TKO Town Centre South Yau Tong Junk Bay Lam Tin Interchange TKO Area 86 January 2012 Project Information Legends: Benefits Proposed Interchange • Upon completion of Route 6, the new road • The existing Tseung Kwan O Tunnel is operating Kai Tak Tseung Kwan O - Lam Tin Tunnel network will relieve the existing heavily near its maximum capacity at peak hours. The trafficked road network in the central and TKO-LT Tunnel and CBL will relieve the existing Kowloon Bay Cross Bay Link eastern Kowloon areas, and hence reduce travel traffic congestion and cater for the anticipated Kwun Tong Trunk Road T2 time for vehicles across these areas and related traffic generated from the planned development Yau Ma Tei Central Kowloon Route environmental impacts. of Tseung Kwan O. To Kwa Wan Lam Tin Tseung Kwan O Table 1: Traffic Improvement - Kwun Tong District Yau Tong From Yau Tong to Journey Time West Kowloon Area (Peak Hour) Current (2012) 22 min. Schematic Alignment of Route 6 and Cross Bay Link Via Route 6 8 min. Traffic Congestion at TKO Tunnel The Tseung Kwan O - Lam Tin Tunnel (TKO-LT Tunnel) At present, the existing Tseung Kwan O Tunnel is towards Kowloon in the morning is a dual-two lane highway of approximately 4.2km the main connection between Tseung Kwan O and Table 2: Traffic Improvement - Tseung Kwan O long, connecting Tseung Kwan O (TKO) and East urban areas of Kowloon. -

Electoral Affairs Commission Report

i ABBREVIATIONS Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) Cap 541F (District Councils) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Particulars Relating to Candidates on Ballot Papers Cap 541M (Legislative Council) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Cap 541N Legislative Council Elections) (Application and Payment Procedure) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 APIs announcements in public interest APRO, APROs Assistant Presiding Officer, Assistant Presiding Officers ARO, AROs Assistant Returning Officer, Assistant Returning Officers Cap, Caps Chapter of the Laws of Hong Kong, Chapters of the Laws of Hong Kong CAS Civil Aid Service CC Complaints Centre CCC Central Command Centre CCm Complaints Committee CE Chief Executive CEO Chief Electoral Officer CMAB Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau (the former Constitutional and Affairs Bureau) D of J Department of Justice DC, DCs District Council, District Councils DCCA, DCCAs DC constituency area, DC constituency areas DCO District Councils Ordinance (Cap 547) ii DO, DOs District Officer, District Officers DPRO, DPROs Deputy Presiding Officer, Deputy Presiding Officers EAC or the Commission Electoral Affairs Commission EAC (EP) (DC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) (District Councils) Regulation (Cap 541F) EAC (FA) (APP) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Legislative Council Elections and District Council Elections) (Application and Payment -

Authorization for Temporary Closure

RAILWAYS ORDINANCE (Chapter 519) (Order under section 22(1)) SOUTH ISLAND LINE (EAST) AUTHORIZATION FOR TEMPORARY CLOSURE OF THE OPEN SPACE OF THE SITTING-OUT AREA ON THE SOUTHERN SIDE OF WONG CHUK HANG ROAD NEAR WONG CHUK HANG ROAD GARDEN; PART OF THE OPEN SPACE IN WONG CHUK HANG ROAD GARDEN; PART OF THE OPEN SPACE IN ABERDEEN SPORTS GROUND; A SECTION OF OCEAN PARK ROAD; A FOOTPATH NEAR THE JUNCTION OF ABERDEEN TUNNEL APPROACH ROAD AND THE SLIP ROAD FROM WONG CHUK HANG ROAD TO ABERDEEN TUNNEL; A FOOTPATH ON THE NORTHERN SIDE OF WONG CHUK HANG ROAD GARDEN; SECTIONS OF WONG CHUK HANG ROAD, ABERDEEN TUNNEL APPROACH ROAD, NAM FUNG ROAD, SLIP ROADS NEAR ABERDEEN TUNNEL APPROACH ROAD, HEUNG YIP ROAD; THE OPEN SPACE IN NAM LONG SHAN ROAD SITTING-OUT AREA, NAM LONG SHAN ROAD CHILDREN’S PLAYGROUNDAND REST GARDEN; SECTIONS OF POLICE SCHOOL ROAD, NAM LONG SHAN ROAD, YIP KAN STREET, TONG BIN LANE, YIP FAT STREET, WELFARE ROAD AND SHUM WAN ROAD; A FOOTPATH BETWEEN WONG CHUK HANG ROAD AND HEUNG YIP ROAD; A FOOTPATH BETWEEN YIP KAN STREET AND WONG CHUK HANG ROAD; A FOOTPATH BETWEEN NAM LONG SHAN ROAD COOKED FOOD MARKET AND TAI WONG YE TEMPLE; PART OF THE OPEN SPACE IN KWUN HOI PATH SITTING-OUT AREA; AND SECTIONS OF KWUN HOI PATH AND ABERDEEN PRAYA ROAD In exercise of the powers delegated by the Secretary for Transport and Housing, I, by this order made under section 22(1)(a) of the Railways Ordinance (Chapter 519), authorize – (I) the temporary closure of the open space of the Sitting-out Area on the southern side of Wong Chuk Hang Road near Wong Chuk -

Designated 7-11 Convenience Stores

Store # Area Region in Eng Address in Eng 0001 HK Happy Valley G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0009 HK Quarry Bay Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0028 KLN Mongkok G/F., Comfort Court, 19 Playing Field Rd., Kln 0036 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0077 KLN Kowloon City Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0084 HK Wan Chai G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 HK Sheung Wan G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0094 HK Causeway Bay Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0102 KLN Jordan G/F, 11 Nanking Street, Kln 0119 KLN Jordan G/F, 48-50 Bowring Street, Kln 0132 KLN Mongkok Shop 16, G/F., 60-104 Soy Street, Concord Bldg., Kln 0150 HK Sheung Wan G01 Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Rd C, HK-Macau Ferry Terminal, HK 0151 HK Wan Chai Shop 2, 20 Luard Road, Wanchai, HK 0153 HK Sheung Wan G/F., 88 High Street, HK 0226 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, Cheung King Mansion, 144 Austin Road, Kln 0253 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui East Shop 1, Lower G/F, Hilton Tower, 96 Granville Road, Tsimshatsui East, Kln 0273 HK Central G/F, 89 Caine Road, HK 0281 HK Wan Chai Shop A, G/F, 151 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, HK 0308 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Hart Avenue Plaza, 5-9A Hart Avenue, TST, Kln 0323 HK Wan Chai Portion of shop A, B & C, G/F Sun Tao Bldg, 12-18 Morrison Hill Rd, HK 0325 HK Causeway Bay Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0327 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 7, G/F Star House, 3 Salisbury Road, TST, Kln 0328 HK Wan Chai Shop C, G/F, Siu Fung Building, 9-17 Tin Lok Lane, Wanchai, HK 0339 KLN Kowloon Bay G/F, Shop No.205-207, Phase II Amoy Plaza, 77 Ngau Tau Kok Road, Kln 0351 KLN Kwun Tong Shop 22, 23 & 23A, G/F, Laguna Plaza, Cha Kwo Ling Rd., Kwun Tong, Kln. -

GEO REPORT No. 146

FACTUAL REPORT ON HONG KONG RAINFALL AND LANDSLIDES IN 2001 GEO REPORT No. 146 T.T.M. Lam GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING OFFICE CIVIL ENGINEERING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION FACTUAL REPORT ON HONG KONG RAINFALL AND LANDSLIDES IN 2001 GEO REPORT No. 146 T.T.M. Lam This report was originally produced in May 2002 as GEO Special Project Report No. SPR 2/2002 - 2 - © The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region First published, July 2004 Prepared by: Geotechnical Engineering Office, Civil Engineering and Development Department, Civil Engineering and Development Building, 101 Princess Margaret Road, Homantin, Kowloon, Hong Kong. - 3 - PREFACE In keeping with our policy of releasing information which may be of general interest to the geotechnical profession and the public, we make available selected internal reports in a series of publications termed the GEO Report series. The GEO Reports can be downloaded from the website of the Civil Engineering and Development Department (http://www.cedd.gov.hk) on the Internet. Printed copies are also available for some GEO Reports. For printed copies, a charge is made to cover the cost of printing. The Geotechnical Engineering Office also produces documents specifically for publication. These include guidance documents and results of comprehensive reviews. These publications and the printed GEO Reports may be obtained from the Government’s Information Services Department. Information on how to purchase these documents is given on the last page of this report. R.K.S. Chan Head, Geotechnical Engineering Office July 2004 - 4 - FOREWORD This report presents the factual information on rainfall and landslides in Hong Kong in 2001. -

Corporate 1 Template

Vigers Hong Kong Property Index Series • As a complement to the existing property information related to the Hong Kong property market • To better inform public of the ever-changing residential market as Vigers has selected residential districts or areas which will be impacted by the Objectives territories’ infrastructure project, i.e. the MTR network expansion • To continually get updates from the property market 2 Hedonic model of price measurement Assumption Asset’s value can be derived from the value of its different characteristics Home Price Dependence on the values that buyers have placed on both qualitative and quantitative attributes Hedonic Estimation of the implicit market value of each Regression attributes of a property by comparing sample home prices with their associated characteristics, on a monthly basis Logarithm of transaction price will be used as independent variable for the regression model, whilst logarithm of dependent variables, such as building’s age, floor numbers, floor areas, and regional, district and estate building names will be selected in the model as controls for quality mix, apart from the time dummy variables (which are the most important part of the model), being employed. Methodology 3 The “Vigers Hong Kong Property Price Index Series” provides a perspective to understand movements in the Hong Kong private housing prices, based on the types or locations of properties. By applying the “Hedonic Regression Model”, the Index Series calculate property price changes relative to a base period at January 2017 (Level 100). Every published index represents an average of its latest six individual monthly indexes. All property attributes such as Building Age, Floor Number, Net Floor Size and Estates / Districts used in these calculations are consistent. -

Chung Fun Steven Hung

The Historical Comparative Analysis of the Development and Transformation of Lei Yue Mun and Cha Kwo Ling with Their Tin Hau Temples Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong ABSTRACT Today, Lei Yue Mun and Cha Kwo Ling are still the nearby urban areas and the urban fringe areas respectively. They are squatter areas and both suffer from environmental hygiene problems and lack proper man- agement. The historical development of Cha Kwo Ling exerted superi- ority in the long-term. If compared to Lei Yue Mun, its economic, so- cietal and cultural development performed better. Therefore, the ad- ministrative-governed centers, namely, the ‘Communal Office of the Four Hills’ and the ‘Communal School of the Four Hills’ were devel- oped in Cha Kwo Ling. After the Second World War, Cha Kwo Ling had some nearby local developments, for example, there were built several oil depots and quarry sites next to it. This made Cha Kwo Ling become even more prosperous. This statement can be strengthened by the massive and spectacular occasion of the ‘Tin Hau Festival.’ This grand event is the most popular and large-scale in the urban area. Coincidentally, Lei Yue Mun underwent certain transformations in the 1960s. It became a tourist hot spot for eating seafood. Up to now it is internationally famous which helps maintaining its prosperity. In con- trast, the economic development of Cha Kwo Ling started to deterio- rate because of the urban developments. But there is a sharp differ- ence if residents' sentiments are taken into account. With the success- ful economic development in Lei Yue Mun, its residents become more cold-blooded and snobbish. -

Directors and Parties Involved in the Global Offering

DIRECTORS AND PARTIES INVOLVED IN THE GLOBAL OFFERING HK Electric Investments HK Electric Investments, as constituted by the Trust Deed in A1A1 Hong Kong Company HK Electric Investments Limited A1A1 Trustee-Manager HK Electric Investments Manager Limited, in its capacity as trustee-manager of HK Electric Investments TRUSTEE-MANAGER DIRECTORS AND COMPANY DIRECTORS The Trust Deed requires that: (a) the board of directors of the Trustee-Manager shall at all times comprise the same individuals who serve as directors of the Company; (b) no person shall serve as a director of the Trustee-Manager unless he also serves as a director of the Company at the same time; and (c) no person shall serve as a director of the Company unless he also serves as a director of the Trustee-Manager at the same time. Accordingly, the compositions of the Trustee-Manager Board and the Company Board are the same. The Trust Deed also requires that the memberships of the Company Audit Committee and the Trustee-Manager Audit Committee must be the same. —79— DIRECTORS AND PARTIES INVOLVED IN THE GLOBAL OFFERING The members of each Board are as follows: Name Address Nationality Executive Directors A1A41 CO Sch 3 para 6 Mr. FOK Kin Ning, Canning 10/F, 1 King Tak Street British (Chairman) Kowloon Hong Kong Mr. WAN Chi Tin Flat A, 15/F, Block 10 Chinese (Chief Executive Officer) Braemar Hill Mansions 33 Braemar Hill Road North Point Hong Kong Mr. CHAN Loi Shun Flat A, 16/F, Tower 1 Chinese Island Crest 8 First Street Hong Kong Mrs. -

Report on the 2019 District Council Ordinary Election

ELECTORAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION REPORT ON THE 2019 DISTRICT COUNCIL ORDINARY ELECTION Submitted to the Honourable Mrs Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China 24 February 2020 i ABBREVIATIONS APIs announcements of public interest APRO, APROs Assistant Presiding Officer, Assistant Presiding Officers ARO, AROs Assistant Returning Officer, Assistant Returning Officers BPSS, BPSSs Ballot Paper Sorting Station, Ballot Paper Sorting Stations CC Complaints Centre CCC Central Command Centre CE Chief Executive CEO Chief Electoral Officer CFI Court of First Instance CMAB Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau CMC Crisis Management Committee CSD Correctional Services Department DoJ Department of Justice DC, DCs District Council, District Councils DCC, DCCs designated collection centre, designated collection centres DCCA, DCCAs District Council constituency area, District Council constituency areas DCO District Councils Ordinance (Cap 547) DO, DOs District Officer, District Officers ii DPRO, DPROs Deputy Presiding Officer, Deputy Presiding Officers DPS, DPSs Dedicated Polling Station, Dedicated Polling Stations EA, EAs election advertisement, election advertisements EAC Electoral Affairs Commission EAC (EP) (DC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) (District Councils) Regulation (Cap 541F) EAC (NAC) (DC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Nominations Advisory Committees (District Councils)) Regulation (Cap 541E) EAC (ROE) (GC) Reg Electoral Affairs