Protest and Marginalized Urban Space. 1968 in West Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aircraft Noise in Berlin Affects Quality of Life Even Outside the Airport Grounds

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Eibich, Peter; Kholodilin, Konstantin; Krekel, Christian; Wagner, Gert G. Article Aircraft noise in Berlin affects quality of life even outside the airport grounds DIW Economic Bulletin Provided in Cooperation with: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Suggested Citation: Eibich, Peter; Kholodilin, Konstantin; Krekel, Christian; Wagner, Gert G. (2015) : Aircraft noise in Berlin affects quality of life even outside the airport grounds, DIW Economic Bulletin, ISSN 2192-7219, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin, Vol. 5, Iss. 9, pp. 127-133 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/107601 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu AIRCRAFT NOISE AND QUALITY OF LIFE Aircraft Noise in Berlin Affects Quality of Life Even Outside the Airport Grounds By Peter Eibich, Konstantin Kholodilin, Christian Krekel and Gert G. -

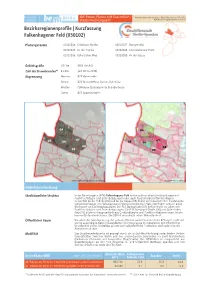

Kurzfassung Falkenhagener Feld

Abt. Bauen, Planen und Gesundheit | Kontakt: Karsten Kruse (Bau 2 Stapl A8) | (030) 90279-2191 | Stadtentwicklungsamt [email protected] Bezirksregionenprofile | Kurzfassung Falkenhagener Feld (050102) Planungsräume 05010204 Griesinger Straße 05010207 Darbystraße 05010205 An der Tränke 05010208 Germersheimer Platz 05010206 Gütersloher Weg 05010209 An der Kappe Gebietsgröße 697 ha (RBS-Fläche) Zahl der Einwohnenden* 41.435 (am 30.06.2018) Abgrenzung Norden: BZR Hakenfelde Süden: BZR Brunsbütteler Damm, Bahnlinie Westen: Falkensee (Landesgrenze Brandenburg) Osten: BZR Spandau Mitte 04 04 05 07 07 06 05 06 08 08 09 09 Digitale farbige Orthophotos 2017 (FIS-Broker) Ausschnitt ÜK50 (FIS-Broker) Gebietsbeschreibung Stadträumliche Struktur In der Bezirksregion (BZR) Falkenhagener Feld finden sich vor allem Großsiedlungen mit Punkthochhäuser und Zeilenbebauungen aber auch freistehende Einfamilienhäuser. In den PLR An der Tränke (05) und An der Kappe (09) finden sich hauptsächlich freistehende Einfamilienhäuser. Im Planungsraum (PLR) Germersheimer Platz (08) finden sich vor allem Blockrand- und Zeilenbebauungen. Der PLR Darbystraße (07) definiert sich vor allem mit Punkthochhäuser und Zeilenbebauungen. Die PLR Griesinger Straße (04) und Gütersloher Weg (06) bestehen hauptsächlich aus Großsiedlungen und Punkthochhäusern sowie freiste- henden Einfamilienhäusern. Die BZR ist ein nahezu reiner Wohnstandort. Öffentlicher Raum Vor allem der Spektegrünzug, der sich von Westen nach Osten durch die BZR zieht, stellt mit seinen ausgiebigen -

“More”? How Store Owners and Their Businesses Build Neighborhood

OFFERING “MORE”? HOW STORE OWNERS AND THEIR BUSINESSES BUILD NEIGHBORHOOD SOCIAL LIFE Vorgelegt von MA Soz.-Wiss. Anna Marie Steigemann Geboren in München, Deutschland von der Fakultät VI – Planen, Bauen, Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie in Soziologie - Dr. phil - Genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzende: Prof. Dr. Angela Million Gutachterin I: Prof. Dr. Sybille Frank Gutachter II: Prof. Dr. John Mollenkopf Gutachter III: Prof. Dr. Dietrich Henckel Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 10. August 2016 Berlin 2017 Author’s Declaration Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis and that this thesis and the work presented in it are my own and have been generated by me as the result of my own original research. In addition, I hereby confirm that the thesis at hand is my own written work and that I have used no other sources and aids other than those indicated. The author herewith confirms that she possesses the copyright rights to all parts of the scientific work, and that the publication will not violate the rights of third parties, in particular any copyright and personal rights of third parties. Where I have used thoughts from external sources, directly or indirectly, published or unpublished, this is always clearly attributed. All passages, which are quoted from publications, the empirical fieldwork, or paraphrased from these sources, are indicated as such, i.e. cited or attributed. The questionnaire and interview transcriptions are attached in the version that is not publicly accessible. This thesis was not submitted in the same or in a substantially similar version, not even partially, to another examination board and was not published elsewhere. -

Kma 2 Kma 1 Interbau 7

WHO IS WHO? — WHO IS WHERE? LANDESDENKMALAMT 65 Dr. Christoph Rauhut 9 Landeskonservator und Leiter des Landesdenkmalamtes 1 Sabine Ambrosius, Referentin für Weltererbe – Altes Stadthaus, Klosterstraße 47, 10179 Berlin, 030 / 90259-3600 [email protected] 50 9 1 2 FRIEDRICHSHAIN 65 KMA 1 9 MIETERBEIRAT Karl-Marx-Allee vom Strausberger Platz 1 bis zur Proskauer und Niederbarnimstraße Vorsitzender: Norbert Bogedein, [email protected] – 61 STALINBAUTEN E.V. 1. Vorsitzender: Achim Bahr, 0160 / 91844921 9 1 [email protected], www.stalinbauten.de KMA UNTERE DENKMALSCHUTZBEHÖRDE FRIEDRICHSHAIN-KREUZBERG VON BERLIN, GEBIET FRIEDRICHSHAIN Till Peter Otto, 030 / 90298 8035, [email protected] FACHBEREICH STADTPLANUNG FRIEDRICHSHAIN-KREUZBERG VON BERLIN Leiter: Matthias Peckskamp, 030 / 90298 2234 [email protected] BEZIRKSSTADTRAT FÜR BAUEN, PLANEN UND FACILITY MANAGEMENT Florian Schmidt, 030 / 90298 3261, [email protected] INTERBAU 1957 – HANSAVIERTEL MITTE KRIEG ARCHITEKTUR UND KALTER BÜRGERVEREIN HANSAVIERTEL E.V. 1. Vorsitzende: Dr. Brigitta Voigt, [email protected], www.hansaviertel.berlin 7 5 UNTERE DENKMALSCHUTZBEHÖRDE MITTE VON BERLIN, ORTSTEILE MOABIT, 9 HANSAVIERTEL UND TIERGARTEN Leiter: Guido Schmitz, 030 / 9018 45887, [email protected] 1 FACHBEREICH STADTPLANUNG MITTE VON BERLIN 59 Leiterin: Kristina Laduch, [email protected] 9 1 STELLVERTRETENDER BEZIRKSBÜRGERMEISTER UND BEZIRKSSTADTRAT FÜR STADTENTWICKLUNG, – SOZIALES UND GESUNDHEIT 57 Ephraim Gothe, 030 / 9018 44600, [email protected] 9 1 INTERBAU 1957 – CORBUSIERHAUS CHARLOTTENBURG BERLIN FÖRDERVEREIN CORBUSIERHAUS BERLIN E.V. Vorsitzender: Marcus Nitschke, 030 / 89742310, [email protected] INTERBAU UNTERE DENKMALSCHUTZBEHÖRDE CHARLOTTENBURG-WILMERSDORF, ORTSTEIL WESTEND Herr Kümmritz, 030 / 9029 15127 [email protected] FACHBEREICH STADTPLANUNG Komm. -

1/5 Bezirksamt Mitte Von Berlin Datum

Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin Datum: 30.12.2019 Stadtentwicklung, Soziales und Gesundheit Tel.: 44600 Bezirksamtsvorlage Nr. 998 zur Beschlussfassung - für die Sitzung am Dienstag, dem 07.01.2020 1. Gegenstand der Vorlage: Beschluss zur Festsetzung der Verordnung über die Erhaltung der städtebaulichen Eigenart aufgrund der städtebaulichen Gestalt für das Gebiet Hansaviertel im Bezirk Mitte von Berlin gemäß § 172 Abs. 1 Satz 1 Nr. 1 BauGB 2. Berichterstatter/in: Bezirksstadtrat Gothe 3. Beschlussentwurf: I. Das Bezirksamt beschließt: Die Verordnung über die Erhaltung der städtebaulichen Eigenart aufgrund der städtebaulichen Gestalt für das Gebiet Hansaviertel im Bezirk Mitte von Berlin gem. § 172 Abs. 1 Satz 1 Nr. 1 BauGB wird festgesetzt. Die Verordnung gilt für das in der anliegenden Karte (Anlage 2) im Maßstab 1:6.000 mit einer Linie eingegrenzte Gebiet. Die Karte ist Bestandteil dieser Verordnung. II. Eine Vorlage an die Bezirksverordnetenversammlung ist nicht erforderlich. III. Mit der Durchführung des Beschlusses wird die Abteilung Stadtentwicklung, Soziales und Gesundheit beauftragt. IV. Veröffentlichung: ja V. Beteiligung der Beschäftigtenvertretungen: nein a) Personalrat: b) Frauenvertretung: c) Schwerbehindertenvertretung: d) Jugend- und Auszubildendenvertretung: 4. Begründung: I. Rechtsverordnung (siehe Anlage) II. Plan mit Geltungsbereich (siehe Anlage) III. Begründung 1/5 1. Beschlussfassung politischer Gremien Das Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin hat in seiner Sitzung am 20.12.2018 die Aufnahme des „Hansaviertels“ in die städtebauliche Förderkulisse (hier: Städtebaulicher Denkmalschutz) beschlossen (Drucksache Nr. 1614/V). Um ein geeignetes städtebauliches Instrument zum Erhalt des „Hansaviertels“ und damit zum Schutz vor baulichen Veränderungen des „Hansaviertels“ zu schaffen, soll eine Verordnung über die Erhaltung der städtebaulichen Eigenart auf Grund der städtebaulichen Gestalt für das Gebiet „Hansaviertel“ beschlossen werden. -

Integriertes Entwicklungskonzept Für Das Gebiet Falkenhagener Feld West (Quartiersbeauftragte: Gesop Mbh)

Entwicklungskonzept Falkenhagener Feld – West Oktober 2005 Anlage 1 j Integriertes Entwicklungskonzept für das Gebiet Falkenhagener Feld West (Quartiersbeauftragte: GeSop mbH) 1. Kurzcharakteristik des Gebiets Die Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld wurde aufgrund ihrer Größenordnung durch das Stadtteilmanagementverfahren in zwei Teilgebiete unterteilt. Aus diesem Grund gibt es vielfach Statistiken/Daten, die über die Abgrenzung der Teilgebiete hinausgehen. Die Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld – West befindet sich beidseitig der Falkenseer Chaussee, westlich der Zeppelinstraße, östlich des „Kiesteiches“, südlich der Pionierstraße und nördlich der Spektewiesen. Bebauungsstruktur Seit dem Jahre 1963 (Baubeginn) wurde auf dem Gebiet des ehemaligen Kleingartenlandes eine Großsiedlung gebaut mit Großsiedlungseinheiten der frühen 60er und 70er Jahre, aus Zeilenbauten, Einzelhäusern und bis zu siebzehngeschossigen Punkthochhäusern. Ab 1990 wurde das Falkenhagener Feld durch Geschosswohnungsbau nachverdichtet; die großzügigen grünen Zwischenräume reduzierten sich. Neben dem Geschosswohnungsbau erstrecken sich auch Siedlungseinheiten aus Einfamilienhäusern durch das gesamte Gebiet. Heute ist die Siedlung (Bereich Ost und West)) mit 56 EW/ha (Vergleich: Spandau 23,5 EW/ha) ein dicht besiedeltes Gebiet, verfügt aber auf Grund der Gesamtgröße, dem relativ hohen Grünanteil und trotz der Nachverdichtung über aufgelockerte Baustrukturen. Mit rund 10 000 Wohneinheiten und knapp 20 000 Einwohnern ist die gesamte Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld nach dem Märkischen Viertel und der Gropiusstadt die drittgrößte Großsiedlung in Berlin (West). Die Siedlung wird durch die Osthavelländische Eisenbahn in die beiden Bereiche Falkenhagener Feld Ost und West geteilt, die jeweils als eigenständige Gebiete für das Stadtteilmanagementverfahren ausgewiesen wurden. Wohnungsbestand Das Falkenhagener Feld West verfügt im Geschosswohnungsbau über knapp 4000 Wohneinheiten. Dieser Bestand hat sich in den letzten Jahren massiv verringert. Durch den Verkauf von Wohnungen sind Eigentumswohnungen entstanden. -

Einwohnerinnen Und Einwohner Im Land Berlin Am 30. Juni 2014

statistik Statistischer Berlin Brandenburg Bericht A I 5 – hj 1 / 14 Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner im Land Berlin am 30. Juni 2014 Alter Geschlecht Familienstand Migrationshintergrund Staatsangehörigkeit Religionsgemeinschaftszugehörigkeit Wohnlage Bezirk Ortsteil LOR-Bezirksregion Anteil Kinder und Jugendlicher mit Migrationshintergrund an allen Personen unter 18 Jahren in Berlin am 30. Juni 2014 nach Ortsteilen in Prozent Anteil in % Berlin: 44,7 unter 25 25 bis unter 50 50 bis unter 75 75 und mehr 0 5 10 km Grünflächen Gewässer Impressum Statistischer Bericht A I 5 – hj 1 / 14 Erscheinungsfolge: halbjährlich Erschienen im September 2014 Herausgeber Zeichenerklärung Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg 0 weniger als die Hälfte von 1 Behlertstraße 3a in der letzten besetzten Stelle, 14467 Potsdam jedoch mehr als nichts [email protected] – nichts vorhanden www.statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de … Angabe fällt später an ( ) Aussagewert ist eingeschränkt Tel. 0331 8173 - 1777 / Zahlenwert nicht sicher genug Fax 030 9028 - 4091 • Zahlenwert unbekannt oder geheim zu halten x Tabellenfach gesperrt p vorläufige Zahl r berichtigte Zahl s geschätzte Zahl Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg, Potsdam, 2014 Dieses Werk ist unter einer Creative Commons Lizenz vom Typ Namensnennung 3.0 Deutschland zugänglich. Um eine Kopie dieser Lizenz einzusehen, konsultieren Sie http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/de/ statistik Statistischer Bericht A I 5 – hj 1 / 14 Berlin BrandenburgBerlin Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Seite Vorbemerkungen 4 3 Deutsche und ausländische Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner in Berlin seit 2003 nach Grafiken Bezirken ................................................................. 7 4 Durchschnittsalter der Einwohnerinnen und 1 Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner mit Migra- Einwohner in Berlin seit 2003 nach Bezirken tionshintergrund in Berlin am 30.06.2014 in Jahren ............................................................... -

Bericht Zur Bevölkerungsprognose Für Berlin Und Die Bezirke 2018 – 2030

Bevölkerungsprognose für Berlin und die Bezirke 2018 – 2030 Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen Ref. I A – Stadtentwicklungsplanung in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg Berlin, 10. Dez. 2019 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Vorbemerkungen und Ergebnisübersicht ……………………………………2 2. Ergebnisse für die Gesamtstadt und die Bezirke ……………………………………7 3. Prognoseannahmen und -varianten …………………………………..14 4. Anhang – Kartenmaterial …………………………………..37 1 1. Vorbemerkungen und Ergebnisübersicht 1.1 Vorbemerkung Mit der „Bevölkerungsprognose für Berlin und die Bezirke 2018 – 2030“ wird zum siebenten Mal durch die Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen eine Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Berlin vorgelegt. Das Wissen über künftige Tendenzen der Bevölkerungsentwicklung ist unerlässlich für die Ausrichtung von Stadtentwicklungspolitik. Hierbei dient die Prognose als Arbeitsgrundlage und Orientierungshilfe für Fachleute aus Planung und Politik. Die Bevölkerungsprognose ist sowohl auf das gesamtstädtische Planungsgeschehen ausgerichtet als auch Planungsgrundlage auf bezirklicher Ebene und für kleinere Gebietseinheiten mit spezifischen sozioökonomischen Gegebenheiten. Der zukünftige Bedarf an benötigter sozialer und technischer Infrastruktur hängt wesentlich von den demografischen Entwicklungen in einem Gebiet ab. Die damit befassten Verwaltungen und Institutionen greifen auf die Bevölkerungsprognose als Bestandteil der Planungsgrundlagen zurück. Die Prognose weist daher Ergebnisse auf Ebene der Gesamtstadt als Grundlage -

Familienzentren in Spandau

Familienzentren in Spandau Stand März 2019 Grußwort -Familienzentren- Liebe Familien, mit dieser kleinen Broschüre erhalten Sie eine Übersicht der in Spandau vorhandenen Familienzentren und deren vielfältigen Angeboten. Die Idee, ein niedrigschwelliges und jederzeit verfügbares Hilfsangebot insbesondere für Familien einzurichten, ist vor rund zehn Jahren entstanden und hat inzwischen einen festen Platz im bezirklichen Angebot für Jugend und Familie. Aus den anfänglich drei Einrichtungen wurde mit Hilfe der zuständigen Ämter, vieler freier Träger und nicht zuletzt mit vielen ehrenamtlich tätigen Bürgerinnen und Bürgern ein Netz aus jetzt neun Familienzentren gebildet. Die gute Resonanz zeigt, wie wichtig und richtig diese Bemühungen waren. Ich hoffe, dass die Familienzentren auch weiterhin gut genutzt werden und danke allen Beteiligten für Ihren Einsatz. Schauen Sie doch mal vorbei! Ihr Stephan Machulik Bezirksstadtrat für Bürgerdienste, Ordnung und Jugend Familienzentrum Villa Nova Rauchstr. 66, 13587 Berlin FiZ Falkenhagener Feld West Wasserwerkstr. 3, 13589 Berlin FiZ Falkenhagener Feld Ost Hermann-Schmidt-Weg 5, 13589 Berlin Familienzentum Kita Lasiuszeile Lasiuszeile 6, 13585 Berlin Familienzentrum Stresow Grunewaldstr. 7, 13597 Berlin Familienzentrum Rohrdamm Voltastr. 2, 13629 Berlin Familienzentrum Hermine Räcknitzer Steig 12, 13593 Berlin Familientreff Staaken Obstallee 22d, 13593 Berlin Familienzentrum Wilhelmine Weverstr 72, 13595 Berlin Ortsteil Familienzentrum Träger E-Mail Hakenfelde Villa Nova Kompaxx e.V. [email protected] Falkenhagener FiZ Humanistischer fiz-wasserwerkstrasse@ Feld Falkenhagener Feld West Verband Deutschlands humanistischekitas.de FiZ FiPP e.V. [email protected] Falkenhagener Feld Ost Familienzentrum familienzentrum-lasius@ Mitte Juwo – Kita gGmbH Kita Lasiuszeile jugendwohnen-berlin.de Familienzentrum Ev. Kirchengemeinde s.schimke@familienzentrum- Stresow St. Nikolai stresow.de Siemensstadt Familienzentrum Kompaxx e.V. -

A Interbau E a Requalificação Moderna Do Oitocentista Hansaviertel Em Berlim - 1957

A INTERBAU E A REQUALIFICAÇÃO MODERNA DO OITOCENTISTA HANSAVIERTEL EM BERLIM - 1957 Mara Oliveira Eskinazi FORMAÇÃO E FILIAÇÃO ACADÊMICA: Arquiteta e Urbanista, formada em 2003/02 pela Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). Mestranda desde 2005/02 do Programa de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura (PROPAR) da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). ENDEREÇO: Rua Gen. Florêncio Ygartua, 491/23 Bairro Rio Branco CEP: 90.430-010 Porto Alegre – RS – Brasil telefones: (51) 3332-3576/ (51) 9126-7668 fax: (51) 3222-4246 e-mail: [email protected] A INTERBAU E A REQUALIFICAÇÃO MODERNA DO OITOCENTISTA HANSAVIERTEL EM BERLIM – 1957 RESUMO O Hansaviertel, bairro oitocentista cuja formação original era bastante integrada ao tecido urbano tradicional predominante na cidade de Berlim, foi em grande parte destruído com os bombardeios da II Guerra Mundial. De localização extremamente central na cidade, o que de fato é hoje dele conhecido é o resultado de uma requalificação arquitetônica e urbanística realizada na década de 50 em decorrência da Interbau (Internationale Bauausstellung) - primeira Exposição Internacional de Arquitetura ocorrida após a II Guerra Mundial. A exposição, que trouxe para a paisagem do parque Tiergarten projetos de edifícios residenciais que expressam valores políticos como a liberdade e o pluralismo, utilizou-se do lema conhecido como “a cidade do amanhã” (die Stadt von Morgen) entre suas premissas básicas para a criação de uma área habitacional modelo do Movimento Moderno. Em 1953, o Senado de Berlim estabelece que a reconstrução do bairro Hansaviertel seja ligada a uma exposição internacional de arquitetura moderna. -

Hollywood Im Hansaviertel 2020

BÜRGERVEREIN HANSAVIERTEL E.V. Wir halten das Verzeichnis zum kostenlosen Download bereit: https://hansaviertel.berlin/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Hollywood-im-Hansaviertel.pdf Die „Stadt von morgen“ als Inhalt: Filmset. Ein Gastbeitrag I. Vorbemerkung II. Das Hansaviertel in Film und Fernsehen III. Angaben zur Benutzung IV. Achtung, wir drehen! Die Filme im Hansaviertel © 2021 Michael Stemmer, Berlin V. Nicht verifizierbare Produktionen im Hansaviertel VI. Wer hier spielte (Auswahl) Kleines Personenregister der Darsteller und Darstellerinnen von Film und Fernsehen in alphabetischer Reihenfolge, die im Hansaviertel auftraten VII. Schöne Aussicht auf die Stars Das ehemalige Kino „Bellevue“ Kino Kongreßhalle VIII. Wo sie wohnten … Kleiner Straßenführer zu den Domizilen bekannter Persönlichkeiten aus Film und Fernsehen im alten und neuen Hansaviertel Wo sie wohnen IX. Motivliste Hansaviertel (Bauten der „Interbau 57“) Was sieht man wo On Location im alten Hansa-Viertel X. Bildhinweis XI. Der Autor 1 Die Hauptstadtregion ist Deutschlands beliebtester Film- und Fernsehschauplatz. Martin Pallgen, Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt 2016 I. VORBEMERKUNG Berlin ist bekanntermaßen eine Metropole im steten Fortschritt und nichts bekundet diese ewige Umgestaltung besser als die Wandelbarkeit seiner Baukunst, verewigt in Filmen aus der und über die Hauptstadt. Deren Kulisse dient immer öfter als begehrtes Szenenbild für zahllose Kino- oder Fernsehfilme. Seit der Er- findung der Kinomatografie surren hier die Kameras. Nicht umsonst macht ein aufgelockertes, mit viel Grün durchzogenes Quartier mit 36 Einzelbauten oder En- sembles des südöstlichen, zwischen Stadtbahnviadukt und Tiergarten gelegenen Teils des im Zweiten Weltkrieg fast vollständig zerbombten gutbürgerlichen Han- saviertels noch heute eines der hervorstechendsten Denkmale des Architektur und Städtebaus der 1950er Jahre aus, das gleich nach seinem Entstehen von Mo- tiv-Suchern der Filmindustrie als inspirierender Drehort entdeckt wurde. -

Office Market Profile Berlin Berlin: Sobering Second Quarter in the Berlin Office Letting Market

Q2 | July 2021 Research Germany Office Market Profile Berlin Berlin: Sobering second quarter in the Berlin office letting market There was a total take-up of around 365,800 sqm in the Development of Main Indicators Berlin office letting market over the first six months of 2021. This is a rise of around 6% compared to the same period the previous year. The second quarter contri buted 148,000 sqm, which means that an average first quarter was followed by a weak second quarter. The market uncertainties as a result of the COVID19 pande- mic have left their mark on demand. Nevertheless, there were three lettings concluded in the >10,000 sqm size category over the last three months. The most active tenant was Bundesanstalt für Immobilienaufgaben (BIMA, Institute for Federal Real Estate) which leased 19,400 sqm in the submarkets Northern Suburb and 14,800 sqm Eastern Suburb. The most active sectors over the first half of the year were the public sector and 3.9%. The combination of a lack of highly priced lettings banks and financial services providers, which together and the increase in the number of lowpriced transac- accounted for around 30% of takeup. The lack of de- tions has resulted in a slight fall in the weighted average mand and the increasing number of unlet newly com- rent from €26.47/sqm/month to €26.26/sqm/month. The pleted properties are now noticeable from the steady prime rent has remained stable at €38.00/sqm/month. rise in the vacancy rate, which increased by 0.5% points compared to the previous quarter to its current level