The Republic of Plato Books I.-V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oecd Development Centre

OECD DEVELOPMENT CENTRE Working Paper No. 137 (Formerly Technical Paper No. 137) A SIMULATION MODEL OF GLOBAL PENSION INVESTMENT by Landis MacKellar and Helmut Reisen Research programme on: Macroeconomic Interdependence and Capital Flows August 1998 CD/DOC(98)7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. 6 RÉSUMÉ .......................................................................................................... 7 SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 7 PREFACE ........................................................................................................ 9 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 11 I. DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS ......................... 13 II. A SIMULATION MODEL ........................................................................... 17 III. SIMULATION RESULTS ........................................................................... 21 IV. CONCLUSION .......................................................................................... 35 NOTES ........................................................................................................... 37 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................. 39 ANNEX 1: THE IIASA MULTIREGIONAL ECONOMIC-DEMOGRAPHIC MODEL ......................................... 41 ANNEX -

Using C-Kermit 2Nd Edition

<< Previous file Chapter 1 Introduction An ever-increasing amount of communication is electronic and digital: computers talking to computers Ð directly, over the telephone system, through networks. When you want two computers to communicate, it is usually for one of two reasons: to interact directly with another computer or to transfer data between the two computers. Kermit software gives you both these capabilities, and a lot more too. C-Kermit is a communications software program written in the C language. It is available for many different kinds of computers and operating systems, including literally hundreds of UNIX varieties (HP-UX, AIX, Solaris, IRIX, SCO, Linux, ...), Digital Equipment Corporation (Open)VMS, Microsoft Windows NT and 95, IBM OS/2, Stratus VOS, Data General AOS/VS, Microware OS-9, the Apple Macintosh, the Commodore Amiga, and the Atari ST. On all these platforms, C-Kermit's services include: • Connection establishment. This means making dialup modem connections or (in most cases) network connections, including TCP/IP Telnet or Rlogin, X.25, LAT, NET- BIOS, or other types of networks. For dialup connections, C-Kermit supports a wide range of modems and an extremely sophisticated yet easy-to-use dialing directory. And C-Kermit accepts incoming connections from other computers too. • Terminal sessions. An interactive terminal connection can be made to another com- puter via modem or network. The Windows 95, Windows NT, and OS/2 versions of C-Kermit also emulate specific types of terminals, such as the Digital Equipment Cor- poration VT320, the Wyse 60, or the ANSI terminal types used for accessing BBSs or PC UNIX consoles, with lots of extras such as scrollback, key mapping, printer con- trol, colors, and mouse shortcuts. -

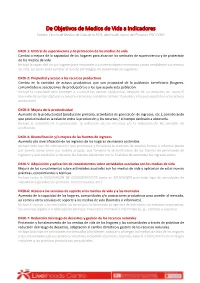

ERC-ECHO. from Objectives to Indicators SP

De Objetivos de Medios de Vida a Indicadores Fuente: Centro de Medios de Vida de la FICR, dentro del marco del Proyecto ERC-ECHO DKOI-1: Umbral de supervivencia y de protección de los medios de vida Cambio o mejora de la capacidad de los hogares para alcanzar los umbrales de supervivencia y de protección de los medios de vida. Incluye la capacidad de los hogares para responder a sus necesidades inmediatas y para restablecer sus medios de vida, así como para cambiar el uso de estrategias de supervivencia negativas. DKOI-2: Propiedad y acceso a los recursos productivos Cambio en la cantidad de activos productivos que son propiedad de la población beneficiaria (hogares, comunidades o asociaciones de producción) o a los que accede esta población. Incluye la capacidad para proteger o sustituir los activos productivos después de un desastre, así como el aumento de su cantidad y/o su mejora o el acceso a mejores activos. Considera el acceso equitativo a los activos productivos. DKOI-3: Mejora de la productividad Aumento de la productividad (producción primaria, actividades de generación de ingresos, etc.), considerando que productividad es la relación entre la producción y los recursos / el tiempo dedicado a obtenerla. Incluye el aumento de la producción, la reducción de los recursos y/o la reducción de las pérdidas de producción. DKOI-4: Diversificación y/o mejora de las fuentes de ingresos Aumento y/o diversificación de los ingresos de los hogares de manera sostenible. Incluye todo tipo de intervención que promueva y fortalezca la creación de empleo formal o informal (tanto por cuenta ajena como por cuenta propia), que fomente la diversificación de las fuentes de generación de ingresos y que estabilice y refuerce las fuentes existentes con la finalidad de aumentar los ingresos netos. -

Lethbridge District 1994 Mar E to M

48 ENCHANT—ETZIKOM Nicko! Geoff Turm 739-2199 TRANSALTA UTIUTIES CORPORATKM G & E INSURANCE SERVICE Nielroer Ronald 739-3759 Vauahan OriicG Nikkei Alvin 739-3761 1301 1 Av N Vauvhos 6S44262 LTD Nofcen Energy Resources Uinited uuIb noiv Plelufo Bullc OltlceCM '0' Orotor(W O"*, : Canadian RQllonsI Alines(tetal 338H<$nw»&vN Piclure Bulls 732-4550 South 739-3966 6 AsS For Zrtll)2211 >«».' 327-9700 Losl LSM 739-2042 Emcrscncy CMS Only 24 Hrs Air Qvtvs CcUc Iradt 739-2230 Northstar Energy Corp 7uHn Cos Vaujhaa OllicB 654-1? asm 235-8165 Gendannerie Royale Du Canada Plant 739-3755 PIclurc Sulle Otflcc-Caa 'IT Op»ki fa AfiFrarrstratKirr 317 2 StN Fo line 739-3777 6Askfor 1921 Mn« MajraA D'S UUAn:^ 329-0355 ptsfilcs 24 Hr 654-2411 TuckerBm ....• AdministrBiiciivlnlD Vaailiss 654-2447 NOVA CORPORATION OF Unruh David 739-^S Geremia B Vajxias 739-2146 Vandcnberg Jacl< b<i«1896 5iSo CANADIAN WESTERN Geremia David - 739-2247 ALBERTA VanNisfelrooy A "''Sh NATURAL GAS GIBSON PETROLEUM ... Wys725-3787 ZA Ht Emcfscrtcy Service VanNistelrooy John H????! GKtespie &ther fArs 739-3774 Cal Co^ct C«HdAry 2S2'8821 Varhaug Henry 739-4144 Gb Serves GBesne G^B B<»1SS4 739-2293 5313SDAvrCcfiscn Tslsr 223-9691 Nova Corporation Of Alberta VAUXHALL DRUGS GOVERNMENT OF ALBERTA 415 2Avtr vauwa 654-2519 AFTBl HOURS EheSGENCV Inlcrmsticn TeW>ons Errjiiry TraversHeiwSieliori 739-3007 CAU. to>arieiie aar-dssi Rile NurrCcr LciMkj^*381-S151 Olson Qifiord 8exldl3 739-3915 VAUXHALL MEAT Si SAUSAGE LTO Olson H®6ld 6cotl83l 739-2162 Central Air Ccndtlonlng r^iorsnliceshc & Tno/Traiuq LeilibnOso 381-5380 403 1 Av S Varinai 6S^Z3X'> Olson Harold Boxissi 739-3930 VmoiA^. -

Syntax of Classical Greek from Homer to Demosthenes

}' (S4^5 SYNTAX OF CLASSICAL GREEK FROM HOMER TO DEMOSTHENES First Part THE SYNTAX OF THE SIMPLE SENTENCE EMBRACING THE DOCTRINE OF THE MOODS AND TENSES BY BASIL LANNEAU GILDERSLEEVE WITH THE CO-OPERATION Op' CHARLES WILLIAM EMIL MILLER OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY NEW YORK •:• CINCINNATI •:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Copyright, iqoo, by B. L. GiLDERSLEHVB. Entered at Stationers' Hall, London. Greek Syntax. W. P. I PREFACE In compliance with the wishes of many of my former pupils, I have determined to pubHsh my Greek Syntax in parts. The framework was planned many years ago, and corresponds in its structure to the scheme of my Latin Grammar, the first edition of which was published in 1867. In fact, the Latin Syntax was based on the MS of the Greek, Doubtless the syntactician of to-day will find ample opportunity to criticise the arrangement, but to refashion the book would require more time than the speeding years will allow me to presume on. Nor will I under- take in this place a vindication of the principles that have guided me in my syntactical studies. A word, however, as to the order of the examples may be deemed appropriate. A catena of syntactical usage would be a memorable achievement, and I do not deny that at one time I thought it possible to organize such a work, for which a large staff of helpers would have been needed; but I have learned to renounce this ambitious scheme, and even the present far more modest undertaking would have been impossible unless I had associated with myself a scholar who is acquainted with* every detail of my syntactical work, publish- ed and unpublished, and who has brought to the task not only a hearty sympathy with my views and methods, but a clearness of judgment and an accuracy in details that have been of great service to me in my own researches. -

The Alberta Gazette

The Alberta Gazette Part I Vol. 101 Edmonton, Friday, April 15, 2005 No. 7 APPOINTMENTS (Provincial Court Act) Supernumerary Judge Re-Appointed April 1, 2005 The Honourable Judge Douglas M. McDonald RESIGNATIONS AND RETIREMENTS (Provincial Court Act) Death of Master March 29, 2005 Master John Peter Floyd ORDERS IN COUNCIL O.C. 121/2005 (Municipal Government Act) Approved and ordered: Norman Kwong Lieutenant Governor. March 8, 2005 The Lieutenant Governor in Council orders that (a) effective January 1, 2005, the land described in Appendix A and shown on the sketch in Appendix B is separated from the Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 and annexed to the Town of Crossfield, (b) any taxes owing to the Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 at the end of December 31, 2004 in respect of the annexed land are transferred to and THE ALBERTA GAZETTE, PART I, APRIL 15, 2005 become payable to the Town of Crossfield together with any lawful penalties and costs levied in respect of those taxes, and the Town of Crossfield upon collecting those taxes, penalties and costs must pay them to the Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44, and (c) the assessor for the Town of Crossfield must assess, for the purpose of taxation in 2005 and subsequent years, the annexed land and the assessable improvements to it. Shirley McClellan, Acting Chair. APPENDIX A DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF THE LANDS SEPARATED FROM THE MUNICIPAL DISTRICT OF ROCKY VIEW NO.44 AND ANNEXED TO THE TOWN OF CROSSFIELD THE NORTHWEST QUARTER OF SECTION TWENTY FOUR (24), TOWNSHIP TWENTY EIGHT (28), RANGE ONE (1), WEST OF THE FIFTH MERIDIAN, WHICH LIES GENERALLY EAST OF THE EXISTING TOWN BOUNDARY, INCLUDING SUBDIVISION PLAN 911 1798, ALL THAT PORTION OF THE GOVERNMENT ROAD ALLOWANCE NORTH OF SAID QUARTER SECTION, THE ROAD WIDENING ALLOWANCE 549 EZ AND THAT PORTION OF ROAD PLAN 741 0378 COMMENCING AT THE SOUTHERN MOST PORTION OF SAID QUARTER SECTION AND PROCEEDING NORTHERLY TO THE NORTHERN MOST PORTION OF SAID QUARTER SECTION. -

Nv Pioneerlocal.Com Xr

Nv pioneerlocal.comxr JANUARY 22, 2009 * A PIONEER PRESS PUBLICATION * $2.00 24/7 COVERAGE SUBURB ODDITIES BLOGS SPORTS DA$LY NEWS FROMYOUR WACKY CROOKS AND ENTERTAINING IDEAS LOOKS HEARD IN THE HALLS LOCAL SOURCE THEIR CRIMES AT POP CULTURE ARTS ATHLETIC BLOG NILES Y'ALD-SPEÇPTOR THIS WEEK FOOD rF4 TOP CHEF Wilmette man competes on Food Network. SEE PIONEERLOCALCOM HOME STAIN PAIN Locas drydeaners share About 100 players participated at the Texas Hold 'em Tournament Sunday at Notre Dame High tips on cleaning WH EN TO School cafeteria to benefit the school's athletic program. Joe Bahi, of South Elgin, Jeff Bagnall1 V of hiles, and Tom Bagnaft, of Chicago were among them. Bagnall wins a hand and gathers his problems. chips. PAGE 5. oîo BY HERB SHENKIN/FOR PIONEER PRESS SEE PIONEERLOCALCOM SERVING OUR READERS SINCE 1951 * YOUR LOCAL SOURCE . Visit Oakton. Come and discover why Oakton is the ideal place to begin or continue your college education. o:t,û9 -lI s1: Wednesday, February 11, at 9:30 a.m. J_ No1:io M 09G9 . Room P103, Skokie campus 4_sra AèJ::f?4Il3Ilafld 9:-1J:N j:;TO OX18fl4 S31XN Reserve your seat atwww.oakton.edu. co!3000 , Oakton OO-3:ijo13O3 Bi94: \ fCommunity College7701 North Lincoln Avenue, Skokie I /a Pionnes Orean Publisolion 50100100' llora l'i,lrhiniroi,io MARINO REALTORS Baild & Warnwr has rw(ocwtdol ours Park Ridge area sales operations to ntuy 5800 Dempster-Morton Grove WY,, 5430-Wo Devise Avenue - 847,823.i.R55, Glenbrook acea sales operations to our ERanston Office (847)967-5500 located sG 2926 Central StreeG - 847.724.1855847.491.1855. -

The Westfield Leader the Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper in Union County

THE WESTFIELD LEADER THE LEADING AND MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPER IN UNION COUNTY JntM I YEAR—No. 9 at WcBtfield. N. J WESTRKLD, NEW JKKSEV 07090. THUfiSDAY. OCTOBER 20. 1966 g» Pledge To Fight Parkway Tolls Thi' Political Scene Candidates7 Views ; Overwhelming Citizen Support l'rc-hnid.r, Walter K 1'liich, On Local Issues j Harry V <.isln>nie .)r. and Kduard H. j Tiller revealed today (liiit thousands | oi area reMilcnls have answered an .Michael Conner KO1IKKT FFJMiUSOlN j advertisement which tiny placed m <»—WAKD 2) lit—WAKI) :)) ; the Wcsllii'lil Lender pledging an all- i Michael Conner. Democratic i'an- Hobcrl ti. Fcraison. Third Ward jmit light against lull.s I,,, i|U. i;,mi], • didale for Town Council troiu 111- .'ouncilriian ninniug for re-election ;VKI Middlesex ('oiiniie.s sections of ! S,'^'i>nc1 W;wd has appointed .hiim j lo a tie IMU year term, today 'ho (.iarden Slate Pkwy. 1 Piiylon Conger, STIi. as his cam-1 described i(i as a "creative year" i paign manager. iin" Council "Much has been accom- "Letters poured in with campaign plished lor Ihe overall benefit of Ihe donations, pledges cir assistance ami j Mr. Conger is a graduate of liar- [ vard College. Hie (ieiieral Thewlogi- town and for Third Ward residents,' vehement lieiinneialion ol <iov. Iticli- Mr. Ferguson declared. iird J. Ilimhes and Now Jersey I cal Seminary in New York and is Democratic senators and assembly | ciitrently studying for his Doctor of Councilman Ferguson spelled out men who attempted lo ftijsl the proj- ]! Philosophy degreg e in Knglisg h a! eight council programs, already in , I'll (in the .shoulders (if tin1 taxpayers | New York University. -

O'zbekiston Respublikasi Oliy Va

O’ZBEKISTON RESPUBLIKASI OLIY VA O’RTA MAXSUS TA`LIM VAZIRLIGI BUXORO MUHANDISLIK - TEXNOLOGIYA INSTITUTI ‘Elektrotexnika va ishlab chiqarishda axborot kommunikatsiya texnologiyalari’ fakulteti ‘Informatika va axborot texnologiyalari’ kafedrasi INFORMATIKA VA AXBOROT TEXNOLOGIYALARI FANIDAN Amaliy ishlar va ularni bajarish uchun USLUBIY KO’RSATMA 1 qism Buxoro – 2015 y. 1 Ushbu uslubiy qo’llanma oliy o’quv yurtlarida turli mutaxassisliklar bo’yicha ta`lim oluvchi talabalar va o’qituvchilar uchun mo’ljallangan. Qo’llanmada yoritilgan materiallardan har bir mutaxassislikka doir ishchi dasturda ko’rsatilgan soatlar asosida kengaytirilib yoki qisqartirilgan holda foydalanish mumkin. Qo’llanmada amaliy ishlarda bajarish uchun turli mavzulardagi __ ta ish keltirilgan. Tuzuvchilar: R.B. Sariev., BuxMTI ‘Informatika va axborot texnologiyalari’ kafedrasi katta o’qituvchisi. S.S. Raxmatov., BuxMTI ‘Informatika va axborot texnologiyalari’ kafedrasi assistenti. Taqrizchilar: f-m.f.n., dots. J. Jumaev, Bux DU ‘Axborot texnologiyasi va tizimlari’ kafedrasi. f.-m. f. n., dots. O.O Yodgorov, BuxMTI ‘Informatika va axborot texnologiyalari’ kafedrasi. 201___ yil ‘___’ ___________ ‘Informatika va axborot texnologiyalari’ kafedrasi umumiy majlisida muhokama qilindi va ma`qullandi. Fakultet o’quv-uslubiy kengashida tasdiqlandi (Bayon № ‘ ___’__________ 201___ y.). Institut o’quv-uslubiy kengashida tasdiqlandi (Bayon № ‘ ___’__________ 201___ y.). 2 Mundarija KIRISH ……………………………………………………..………………….. 4 I. AXBOROT NAZARIYASI VA MA`LUMOTLARNI KODLASH ASOSLARI 1.1. Amaliy ish. Ma`lumotlarni kodlash………………………………….… 5 II. AXBOROT JARAYONLARINING APPARAT TA`MINOTI 2.1. Amaliy ish. Zamonaviy kompyuter qurilmalarining tasnifi …..….. 13 III. AXBOROT JARAYONLARINING DASTURIY TA`MINOTI 3.1. Amaliy ish. Dasturiy ta`minot tahlili …………………………….... 19 IV. OPERATSION TIZIMLAR 4.1. Amaliy ish. Operatsion tizim foydalanuvchi interfeysi va fayl menejeri .……………………………………………………………….. 23 4.2. Amaliy ish. -

Multimédia Szoftver Szabványok

Multimédia szoftver szabványok HEFOP 3.5.1 Korszerű felnőttképzési módszerek kifejlesztése és alkalmazása EMIR azonosító: HEFOP-3.5.1-K-2004-10-0001/2.0 Tananyagfejlesztő: Máté István Lektorálta: Brückler Tamás Felelős kiadó: Dr. Fodor Imréné PRKK 2007 Akkreditációs lajstrom szám: 0013 Nyilvántartási szám: 02-0154-05 Máté István Multimédia szoftver szabványok A modulfüzet alapadatai SZAKMACSOPORT: Informatika SZAKMA: Multimédia fejlesztő MODUL: Multimédia szabványok Bemeneti követelmények: A modulhoz a számítástechnikai és multimédia alapismeretek, az integ- rált irodai programcsomag használata, valamint az internet felhasználói ismeretek modul megtanulása szükséges. A modul célja: A hallgató a multimédia szabványok modul elvégzése után képes legyen multimédiához kapcsolódó adattárolási, adatátviteli, adattömörítési, hardver csatolófelület és a médiumokhoz kapcsolódó egyéb szabványok azonosítására és alkalmazására a gyakorlatban, ismerje és használja a szabványokkal kapcsolatos szakkifejezéseket magyarul és angolul. A modul időtartama: 60 óra A modul során elsajátított kompetenciák: Számítógépek szabványos csatolófelületeinek felismerése, csatlakoztatá- sa. Adattárolási szabványok felismerése, tárolási formátumok használata a gyakorlatban. Adattömörítési szabványok elismerése és alkalmazása a gyakorlatban. Adatátviteli megvalósítása a gyakorlatban. Szöveg médium szabványainak felismerése, átalakítás az egyes formá- tumok között az adott helyzetnek megfelelően. Állókép médium szabványainak felismerése, átalakítás az egyes formá- tumok között -

The David Kim Orchestral Institute of Cairn University Violin & Viola Summit June 17 – 24, 2018

The David Kim Orchestral Institute of Cairn University Violin & Viola Summit June 17 – 24, 2018 Application and Auditions Start Date: January 15, 2018 Application and Auditions Deadline: May 1, 2018 -1- Greetings from David Kim I would like to personally invite you to be a part of the third annual Violin & Viola Summit hosted by the David Kim Orchestral Institute. In order to encourage as many students as possible to apply, I made it a point to create an application process that is easy and simple. I have also created a schedule spanning eight days that is varied, stimulating, and fun. I know that we will have participants of all ages from around the world, creating many new friendships that will last a lifetime! –David Kim Concertmaster of the Philadelphia Orchestra Artistic Director of the David Kim Orchestral Institute of, Cairn University Greetings from the Dean of the School of Music Welcome to the David Kim Orchestral Institute of Cairn University. We are delighted to partner with David Kim to offer the world of orchestral music a place for musical and spiritual refreshment. We are thrilled to have you join us for this adventure in world-class music making. This overview book is designed to give you a sense of what it will be like to be a participant. It includes the details of what the audition process will look like, what it will be like to be a student in the summit, and the overarching goals we have for this year. If you have any questions after reading, feel free to send those questions to [email protected]. -

|^3H :Pmmk.» Gpiftjaldllttd ^

72 CESSFORD McBride J A 566-2478 SCEPTRE RESOURCES LTD McKIUcp William J B^tone 566-2255 Cessford Gas Plant McNeil Doug Sunnynook 566-2209 RRSHanna 566-2184 McWIvenMIke ...-. 566-2421 Environment Council Of Alberta McNiven Peter 566-3964 SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED ' Can '0' Opsfator(No Chatge)& Ask For Zenith 06075 MIckler Dan .... > 566-3780 DISEASE & AIDS Esso Resources Cana& Limited Vetgcr MHIs A 566-3790 (No Chsrgo Dial).. > 1-800-772-2437 Compressor Stn S66-37(S6 MOBIL GIL CANADA SUaL CANADA LTD Agt Matziwin Station 566-3925 Olds Area Office 556-3374 326 7SIE Brooks 362-4441 Finkbelner Stewart 566-3782 Plant 566-3939 TedWaktRes Brooks 362-7i^ Flanagan Bob 566-2340 Mountjoy L 566-3778 Flanagan J A BoxlZ6Dudi«s 566-2351 Ridiard Waid Res Brocks 362^5857' Franldln Elaine 566-3740 Napier K 566-2181 Shepherd E Wardiow ^21:^' Fnberger John Wardiow 566-2158 NesterDon 566-2412 Slorstad Brad Sumynnok 566^23M Nester Les 566-3776 Sloistad S J Bbx21Sunnyncok 566V2131' FYKE'S MUSIC CENTRE(BROOKS) Nester Louis 566-2^ SoDierg J A Sunnynook 556-£(^ mc Neve Harriet Mrs .: 566-2370 SoHierg K VSunnynock 556-2223 Cassils Centre Mat Brooks 362—4188 NEWELL VETERINARY CUNIC SPENCE WATER WELL Garlodc Gordon 566-3799 1103 2StW Brooks 362-3273 Gendarmefe Royale Du Canada DRILUNG... ...: ..566^2293 After Hours t 362-3273 stifle John C Box32Sunnynack........i 566-2108 310 4StW Brooks 362-5535 NEWLAKE RESOURCES LTD Gillesple Cameron Finnisan 566-2374 Stringer Lee Suitnyncok '... 566-2232 GiBespIO Oelbert A Fonegan 566-2186 Compnssor Ptant Wardiow ..566-3730 Stringer Mary E Sunnynook 566-212B CniespteMarstiaa 566-2350 Newton Dean 566-2362 SuKor Murray 566^3906' enmour Tom ffisStone 566-2245 NORCEN ENERGY RESOURCES Suitor Pat Box56Diichess 566-2360 government of alberta UNITED 566-2488 Sunstrum Bruce Box35 566-2224' ' CAU.