INDO 21 0 1107106963 65 84.Pdf (1.113Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Indonesian Islam?

M. Laffan, draft paper prepared for discussion at the UCLA symposium ‘Islam and Southeast Asia’, May 15 2006 What is Indonesian Islam? Michael Laffan, History Department, Princeton University* Abstract This paper is a preliminary essay thinking about the concept of an Indonesian Islam. After considering the impact of the ideas of Geertz and Benda in shaping the current contours of what is assumed to fit within this category, and how their notions were built on the principle that the region was far more multivocal in the past than the present, it turns to consider whether, prior to the existance of Indonesia, there was ever such a notion as Jawi Islam and questions what modern Indonesians make of their own Islamic history and its impact on the making of their religious subjectivities. What about Indonesian Islam? Before I begin I would like to present you with three recent statements reflecting either directly or indirectly on assumptions about Indonesian Islam. The first is the response of an Australian academic to the situation in Aceh after the 2004 tsunami, the second and third have been made of late by Indonesian scholars The traditionalist Muslims of Aceh, with their mystical, Sufistic approach to life and faith, are a world away from the fundamentalist Islamists of Saudi Arabia and some other Arab states. The Acehnese have never been particularly open to the bigoted "reformism" of radical Islamist groups linked to Saudi Arabia. … Perhaps it is for this reason that aid for Aceh has been so slow coming from wealthy Arab nations such as Saudi Arabia.1 * This, admittedly in-house, piece presented at the UCLA Colloquium on Islam and Southeast Asia: Local, National and Transnational Studies on May 15, 2006, is very much a tentative first stab in the direction I am taking in my current project on the Making of Indonesian Islam. -

TEUNGKU MUHAMMAD DAUD BEUREUEH DAN REVOLUSI DI ACEH (1945-1950) Bambang Satriya, Suwirta, Ayi Budi Santosa Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia

FACTUM: JURNAL SEJARAH DAN PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH, VOL. 7 NO. 1, 2018 ISSN: 2302-9889, E.ISSN: 2615-515X TEUNGKU MUHAMMAD DAUD BEUREUEH DAN REVOLUSI DI ACEH (1945-1950) Bambang Satriya, Suwirta, Ayi Budi Santosa Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia ABSTRACT ABSTRAK This research was distributed by attractions of Penelitian ini dilatarbelakangi oleh ketertarikan authors to Teungku Muhammad Daud Beureueh penulis kepada sosok Teungku Muhammad the leader with big influence when the revolution Daud Beureueh yang memiliki pengaruh besar happened in Aceh. The main issues studied in this ketika berlangsungnya masa revolusi di Aceh. research is “How was Teungku Muhammad Daud Permasalahan utama yang dibahas adalah adalah Beureueh’s role in defending the independence of “Bagaimana peran Teungku Muhammad Daud Indonesian Republic in Aceh 1945-1950?”. This Beureueh dalam mempertahankan kemerdekaan study uses historical method which includes four Republik Indonesia di Aceh tahun 1945-1950?”. steps: 1) Heuristics, 2) Criticism, 3) Interpretation, Penelitian ini menggunakan metode historis 4) Historiography. Based on the result, the political dengan empat tahapan, yaitu: 1) Heuristik, 2) and socio-economic conditions in Aceh after the Kritik, 3) Interpretasi, dan 4) Historiografi. independence of Indonesian Republic was unstable. Adapun hasil penelitian yang diperoleh bahwa The role of Teungku Muhammad Daud Beureueh kondisi politik dan sosial ekonomi di Aceh pasca in Peristiwa Cumbok gave the awareness to local kemerdekaan tidak stabil. Kemudian, Teungku government to give more attention in this horizontal Muhammad Daud Beureueh berperan penting conflict and he instructing to mobilize the troops dalam Peristiwa Cumbok dengan memberikan to attack the uleebalang clan in Pidie. He also penyadaran terhadap pemerintah daerah agar stopped the Tentara Perjuangan Rakyat (TPR) memerhatikan konflik horizontal yang sedang movement who headed by Husin Al Mujahid. -

NO Store Address Store Location Phone No 1 Gandaria City Jl Sultan Iskandar Muda, Kebayoran Lama, Jakarta. 2Nd Floor, Island Un

NO Store Address Store Location Phone No 2nd Floor, Island Unit Gandaria Jl Sultan Iskandar Muda, Kebayoran #202, In Front of 1 City Lama, Jakarta. Celebrity Fitness 0877 7501 8199 Food Society Ground Floor unit#18, Beside of Kota Jl Raya Casablanca kav.88, Tebet, Remboelan Restaurant / 2 Kasablanka Jakarta Selatan. Levi's Store 0818 885 393 Lotte Lower Ground Floor Shopping Jl Prof Dr. Satrio kav.3-5 Karet unit#39, beside of 3 Avenue Kuningan, Jakarta Selatan Auntie Anne's or BACCO 0817 4848 802 World Trade Basement Floor (next to 4 Center 6 Jl Jend Sudirman kav. 29, Jakarta Dunkin Donuts) 0817 6799 583 Ground Floor unit#15, Jl. Boulevard Jend Sudirman 1110, near to Parking Area / 5 MaxxBox Lippo Village, Tangerang Primo Supermarket 0818 885 395 Lower Ground Floor unit#LG-A, in front of Pacific Jl Jend Sudirman kav. 52- 53, SCBD KemChicks or The Body 6 Place Jakarta, Jakarta Selatan Shop 0817 0116 805 Mall Alam Jl Jalur Sutera Barat kav.16, Pinang, Ground Floor, Island 7 Sutera Alam Sutera, Tangerang Unit#06 0877 7501 8197 Kuningan Jl Prof Dr. Satrio kav.18, Karet Lower Ground Floor Pop 8 City Kuningan, Jakarta Selatan Up Stall I no.2 0811 - 8711302 Gedung Oakwood, Jl Lingkar Mega Kuningan blok E4.2 beside of Grha XL 9 Oakwood no.1, Mega Kuningan, Jakarta Building, First Floor 0817 4848 799 West Mall, Lower Ground (ifo BCA kantor kas Grand Jl MH Thamrin no.1, Menteng, Jakarta Cabang Grand Indonesia 10 Indonesia Pusat / Food Hall), WM-LG-IC-C 0817 4848 803 Rumah Sakit Puri Jl. -

The Punishment of Islamic Sex Crimes in a Modern Legal System the Islamic Qanun of Aceh, Indonesia

CAMMACK.FINAL3 (DO NOT DELETE) 6/1/2016 5:02 PM THE PUNISHMENT OF ISLAMIC SEX CRIMES IN A MODERN LEGAL SYSTEM THE ISLAMIC QANUN OF ACEH, INDONESIA Mark Cammack The role of Islamic law as state law was significantly reduced over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This decline in the importance of Islamic doctrine has been attributed primarily to the spread of European colonialism. The western powers that ruled Muslim lands replaced much of the existing law in colonized territories with laws modeled after those applied in the home country. The trend toward a narrower role for Islamic law reversed itself in the latter part of the twentieth century. Since the 1970s, a number of majority Muslim states have passed laws prescribing the application of a form of Islamic law on matters that had long been governed exclusively by laws derived from the western legal tradition. A central objective of many of these Islamization programs has been to implement Islamic criminal law, and a large share of the new Islamic crimes that have been passed relate to sex offenses. This paper looks at the enactment and enforcement of recent criminal legislation involving sexual morality in the Indonesian province of Aceh. In the early 2000s, the provincial legislature for Aceh passed a series of laws prescribing punishments for Islamic crimes, the first such legislation in the country’s history. The first piece of legislation, enacted in 2002, authorizes punishment in the form of imprisonment, fine, or caning for acts defined as violating Islamic orthodoxy or religious practice.1 The 2002 statute also established an Islamic police force called the Wilayatul Hisbah charged 1. -

Curbing Corruption in Tsunami Relief Operations

Curbing Corruption in Tsunami Relief Operations Proceedings of the Jakarta Expert Meeting organized by the ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia and the Pacific and Transparency International, and hosted by the Government of Indonesia Jakarta, Indonesia 7–8 April 2005 Asian Development Bank Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Transparency International 05-4168CurbingPrelim.pmd 1 27/08/2005, 1:53 PM © 2005 Asian Development Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Transparency International All rights reserved This publication was prepared by the Secretariat of the ADB-OECD Anti- Corruption Initiative for Asia-Pacific comprising staff of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and by Transparency International (TI). The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in it do not necessarily represent the views of ADB or those of its member governments, of the OECD and its member countries, or of Transparency International and its member chapters. ADB, OECD, and TI do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accept no responsibility whatsoever for any consequences of their use. The term “country” does not imply any judgment by ADB, OECD, and TI as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. ISBN 971-561-594-5 Publication Stock No. 080705 Published by the Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980 Manila, Philippines 05-4168CurbingPrelim.pmd 2 27/08/2005, 1:53 PM Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms v Foreword vii Meeting Conclusions and Framework for Action 1 Summary of Proceedings 7 Issue Papers 1. -

Perancangan Buku Ilustrasi Laksamana Keumalahayati

PERANCANGAN BUKU ILUSTRASI LAKSAMANA KEUMALAHAYATI Laporan Tugas Akhir Ditulis sebagai syarat untuk memperoleh gelar Sarjana Desain (S.Ds.) Nama : Nadya Chandra NIM : 00000010581 Program Studi : Desain Komunikasi Visual Fakultas : Seni & Desain UNIVERSITAS MULTIMEDIA NUSANTARA TANGERANG 2019 KATA PENGANTAR Puji syukur yang penulis dapat panjatkan kepada Tuhan Yang Maha Esa atas selesainya Proposal Perancangan Tugas Akhir ini. Besar harapan penulis untuk dapat berperan bagi bangsa dengan mengabadikan jasa salah satu Pahlawan Nasional Wanita Indonesia yaitu Laksamana Keumalahayati yang atas keberanian dan kecerdasannya sempat memporakporandakan dan membuat gentar angkatan laut para penjajah tanah air di bumi Aceh. Melihat fakta bahwa jasa beliau masih kurang dikenang di masyarakat, penulis berkeinginan besar untuk menulis informasi berupa buku ilustrasi untuk khalayak, khususnya untuk anak-anak sekolah dasar yang memiliki keingintahuan yang tinggi. Semoga melalui perancangan tugas akhir ini dapat memberikan inspirasi bagi para pembaca, baik dari laporan maupun hasil karya akhir dan dapat mengingatkan kembali pentingnya untuk mengabadikan sejarah tanah air kita. Terima kasih kepada orang-orang yang telah membantu proses Tugas Akhir penulis, yakni sebagai berikut: 1. Mohammad Rizaldi, S.T., M.Ds., selaku Ketua Program Studi Desain Komunikasi Visual Universitas Multimedia Nusantara. 2. Prima Murti Rane, M.Ds., selaku Dosen Pembimbing. 3. Endang Moerdopo selaku penulis buku Laksamana Keumalahayati serta Bu Retno selaku In-Chief Editor Elex Media Komputindo 4. Donny Djuanda, Nina Chandra, dan Aldo Sebastian Chandra selaku keluarga dan Aditya Satyagraha, S.Sn., M.Ds., Dennis Vincentius, iv ABSTRAKSI Pahlawan Nasional merupakan gelar penghargaan tingkat tertinggi di Indonesia dan gelar tersebut diberikan kepada seseorang atas tindakan yang heroic dan sejauh ini terdapat 173 orang Pahlawan Nasional di Indonesia, yaitu terdiri dari 160 pria dan 13 wanita menurut Menteri Sosial, Khofifah Indar Parawansa. -

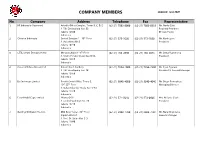

COMPANY MEMBERS Updated: June 2020 2019 No

COMPANY MEMBERS Updated: June 2020 2019 No. Company Address Telephone Fax Representative 1 BP Indonesia (Upstream) Arkadia Office Complex, Tower B, C, D, E (62-21) 7883-8000 (62-21) 7883-8333 Mr. Nader Zaki Jl. T.B. Simatupang Kav. 88 Regional President Jakarta 12520 BP Asia Pacific Indonesia 2 Chevron Indonesia Sentral Senayan 1 - 18th Floor (62-21) 573-1020 (62-21) 573-1030 Mr. Kevin Lyon Jl. Asia Afrika No.8 President Jakarta 10270 Indonesia 3 CITIC Seram Energy Limited Menara Citibank - 6th Floor (62-21) 766-2840 (62-21) 766-2845 Mr. Deng Yuanzhong Jl. Metro Pondok Indah Kav. II BA President Jakarta 12310 Indonesia 4 ConocoPhillips (Grissik) Ltd. Ratu Prabu 2 Building (62-21) 7854-1000 (62-21) 7854-2680 Mr. Bijan Agarwal Jl. T.B. Simatupang Kav. 1B President & General Manager Jakarta 12560 Indonesia 5 Eni Indonesia Limited Pondok Indah Office Tower 3, (62-21) 3040-4000 (62-21) 3040-4040 Mr. Diego Portoghese 19th-22nd Floor Managing Director Jl. Sultan Iskandar Muda Kav. V-TA Jakarta 12310 Indonesia 6 ExxonMobil Cepu Limited Wisma GKBI (62-21) 571-5010 (62-21) 574-0606 Mrs. Melanie Cook Jl. Jendral Sudirman No. 28 President Jakarta 10210 Indonesia 7 Genting Oil Kasuri Pte. Ltd. DBS Bank Tower -16th Floor, (62-21) 2988-7700 (62-21) 2988-7701 Mr. Nara Nilandaroe Ciputra World 1 General Manager Jl. Prof. Dr. Satrio Kav. 3-5 Jakarta 12940 Indonesia COMPANY MEMBERS Updated: June 2020 2019 8 Harpindo Mitra Kharisma, PT Graha Kapital 1 Unit S 303A, 3rd Floor (62-21) 718-0785 (62-21) 719-9613 Mr. -

Eunuchs and Concubines in the History of Islamic Southeast Asia

EUNUCHS AND Moreover, they were always of servile CONCUBINES IN THE status, as the holy law demanded. In Southeast Asia, in contrast, concubines HISTORY OF ISLAMIC (gundik) were sometimes free, and SOUTHEAST ASIA eunuchs (sida-sida) mysteriously dis- appeared around 1700. William Gervase Clarence- 1 Unfortunately, the nature of these Smith practices in Islamic Southeast Asia is hard to unravel, as they are covered by a veil of silence. Servitude itself is seen as highly Abstract embarrassing (Salman 2001). 'Sexual aberrations' merely compound the In the early 17th century, male servant embarrassment, and outsiders writing eunuchs were common, notably at the about such matters easily attract Persianised Acehnese court of Iskandar accusations of 'Orientalism' and Muda. By mid-century, the castration of 'voyeurism.' This is unfortunate, because a male slaves mysteriously disappeared. study of these topics helps to illuminate Concubinage, however, lasted much historical specificities pertaining to both longer. While there were sporadic Islam and sexuality in the region. attempts to stamp out abuses, for example sexual relations with pre-pubescent slave Concubinage in Islam girls, and possibly, clitoridectomy, a reasoned rejection of the institution of Across Islamdom, the ulama accepted that concubinage on religious grounds failed a man could have an unlimited number of to emerge. This paper discusses the sexual servile concubines. Quranic references to treatment of slaves across Islamic 'those whom your right hand possesses' Southeast Asia, a subject which sheds seemed to justify the institution, and the important light on historical specificities Prophet himself was believed to have pertaining to both Islam and sexuality in owned two concubines in the latter stages the region, yet which continues to be of his life (Ruthven 2000: 57, 62-3, Awde treated with silence, embarrassment or 2000: 10, Zaidi 1935). -

Islamic Law and Social Change

ISLAMIC LAW AND SOCIAL CHANGE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE INSTITUTIONALIZATION AND CODIFICATION OF ISLAMIC FAMILY LAW IN THE NATION-STATES EGYPT AND INDONESIA (1950-1995) Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Joko Mirwan Muslimin aus Bojonegoro (Indonesien) Hamburg 2005 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Rainer Carle 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Olaf Schumann Datum der Disputation: 2. Februar 2005 ii TABLE OF RESEARCH CONTENTS Title Islamic Law and Social Change: A Comparative Study of the Institutionalization and Codification of Islamic Family Law in the Nation-States Egypt and Indonesia (1950-1995) Introduction Concepts, Outline and Background (3) Chapter I Islam in the Egyptian Social Context A. State and Islamic Political Activism: Before and After Independence (p. 49) B. Social Challenge, Public Discourse and Islamic Intellectualism (p. 58) C. The History of Islamic Law in Egypt (p. 75) D. The Politics of Law in Egypt (p. 82) Chapter II Islam in the Indonesian Social Context A. Towards Islamization: Process of Syncretism and Acculturation (p. 97) B. The Roots of Modern Islamic Thought (p. 102) C. State and Islamic Political Activism: the Formation of the National Ideology (p. 110) D. The History of Islamic Law in Indonesia (p. 123) E. The Politics of Law in Indonesia (p. 126) Comparative Analysis on Islam in the Egyptian and Indonesian Social Context: Differences and Similarities (p. 132) iii Chapter III Institutionalization of Islamic Family Law: Egyptian Civil Court and Indonesian Islamic Court A. The History and Development of Egyptian Civil Court (p. 151) B. Basic Principles and Operational System of Egyptian Civil Court (p. -

List of Participating Interest (Pi)

LIST OF PARTICIPATING INTEREST (PI) 2014 Information on the technical and financial criteria for license transfers CONTRACTORS THAT TRANSFER INTEREST CONTRACTORS THAT ACCEPT INTEREST NAME OF OPERATOR KKKS APPROVAL DATE OF TRANSFER WORKING AREA NAME ADDRESS NAME2 ADDRESS2 NAME3 ADDRESS3 % TRANSFER (DEED OF ASSIGNMENT) PONDOK INDAH OFFICE TOWER PONDOK INDAH OFFICE TOWER 3, LT.19-22 3, LT.19-22 1 ARGUNI I, WEST PAPUA ENI ARGUNI I LIMITED JL. SULTAN ISKANDAR MUDA GDF SUEZ E&P ARGUNI B.V. - ENI ARGUNI I LIMITED JL. SULTAN ISKANDAR MUDA 4-Aug-2014 20% KAV. V-TA KAV. V-TA JAKARTA 12310 JAKARTA 12310 JL. CIOMAS II NO.1 JL. CIOMAS II NO.1 2 BATANGHARI, JAMBI CNOOC BATANGHARI LTD. - PT GREGORY GAS PERKASA KEBAYORAN BARU PT GREGORY GAS PERKASA 9-May-2014 87% KEBAYORAN BARU JAKARTA 12160 JAKARTA 12160 WORLD TRADE CENTER II, WORLD TRADE CENTER II, BENGKULU-I MENTAWAI, 3 TOTAL E&P INDONESIE MENTAWAI B.V. METROPOLITAN COMPLEX, MUBADALA PETYROLEUM (BENGKULU - TOTAL E&P INDONESIE MENTAWAI B.V. METROPOLITAN COMPLEX, 17-Jul-2014 20% OFF. BENGKULU JL. JEND. SUDIRMAN KAV. 29-31 MENTAWAI) LIMITED JL. JEND. SUDIRMAN KAV. 29-31 JAKARTA 12920 JAKARTA 12920 ARTHA GRAHA BUILDING, LT.26 ARTHA GRAHA BUILDING, LT.26 DISTRICT-LOT 25, DISTRICT-LOT 25, 4 BONE, SOUTH SULAWESI MITRA ENERGY (INDONESIA BONE) LIMITED AZIMUTH INDONESIA LTD. MITRA ENERGY (INDONESIA BONE) LIMITED 28-Mar-2014 40% JL. JEND. SUDIRMAN KAV.52-53 JL. JEND. SUDIRMAN KAV.52-53 JAKARTA 12190 JAKARTA 12190 SENTRAL SENAYAN TOWER II, SENTRAL SENAYAN TOWER II, CENDRAWASIH BAY III, 5 NIKO RESOURCES (OVERSEAS XXIII) LTD. -

SULTAN ISKANDAR MUDA Pendahuluan Hampir Dalam

SULTAN ISKANDAR MUDA Pendahuluan Hampir dalam seluruh aspek kehidupan menunjukkan bahwa zaman Sultan Iskandar muda merupakan masa kegemilangan Aceh. Dia tidak hanya mampu menyusun dan menetapkan berbagai konsep qanun (undang-undang dan peraturan) yang adil dan universal, tetapi juga telah mampu melaksanakan secara adil dan universal pula. Sebagai seorang yang masih sangat muda menduduki tahta kerajaan (usia 18-19 tahun), kesuksesan Sultan Iskandar Muda sebagai penguasa Kerajaan Aceh Darussalam telah mendapat pengakuan bukan hanya dari rakyatnya, tetapi dari musuh-musuhnya dan bangsa asing di seluruh dunia. Sultan Iskandar Muda telah berhasil menyatukan seluruh wilayah semenanjung tanah Melayu di bawah panji kebesaran Kerajaan Aceh Darussalam. Dia juga telah berhasil menjalin hubungan diplomasi perdagangan dengan berbagai bangsa Asing, sehingga secara internasional Aceh tidak hanya dikenal sebagai sebuah negeri yang sangat kaya dengan berbagai sumber daya a!amnya, tetapi kekayaan itu benar-benar dapat dinikmati secara bersama oleh rakyatnya. Dalam bidang ilmu pengetahuan dan pendidikan, dia telah menempatkan para ulama dan kaum cerdik pandai pada posisi yang paling mulia dan istimewa. Sehingga pada masa pemerintahannya, Kerajaan Aceh Darussalam benar-benar menjadi salah satu pusat ilmu pengetahuan dan tamaddun di Asia Tenggara yang paling banyak dikunjungi oleh para kaum pelajar dari seluruh dunia. Selama lebih kurang 30 tahun masa pemerintahannya, yaitu (1606 - 1636 M) dia telah berhasil membawa Kerajaan Aceh Darussalam ke atas puncak kejayaannya, hingga mencapai peringkat kelima di antara kerajaan Islam terbesar di dunia. Silsilah, Kelahiran dan Masa Kecil Sultan Iskandar Muda Sampai saat ini belum diketahui secara pasti mengenai tahun kelahiran Sultan Iskandar Muda. Namun dari hasil identifikasi atas beberapa sumber yang ada menegaskan bahwa dia lahir sekitar tahun 1583. -

LAMPIRAN : KEPUTUSAN MENTERI PERTANIAN NOMOR : 69/Kpts/HK

LAMPIRAN : KEPUTUSAN MENTERI PERTANIAN NOMOR : 69/Kpts/HK.310/8/2001 TANGGAL : 1 AGUSTUS 2001 TENTANG : TEMPAT-TEMPAT PEMASUKAN DAN PENGELUARAN MEDIA PEMBAWA ORGANISME PENGGANGGU TUMBUHAN KARANTINA I. Tempat-tempat Pemasukan (Impor) Media Pembawa Organisme Pengganggu Tumbuhan Karantina ke Dalam Wilayah Negara Republik Indonesia. A. Bandar Udara: 1. Polonia - Medan 13. Sepinggan – Balikpapan 2. Tabing - Padang 14. Supadio - Pontianak 3. Hang Nadim – Batam 15. Juwata – Tarakan 4. St Mahmud Badaruddin II - palembang 16. Sam ratulangi – Menado 5. Halim Perdana Kusuma – Jakarta 17. Hasanuddin – Makassar 6. Soekarno-Hatta – Cengkareng 18. Patimura – Ambon 7. Husein Sastranegara – Bandung 19. Frans Kaisiepo – Biak 8. Adi Sumarmo – Solo 20. Tembaga Pura – Timika 9. Juanda – Surabaya 21. Sentani – Jayapura 10. Ngurah Rai – Denpasar 22. St Iskandar Muda -Banda Aceh 11. Selaparang – Mataram 23. St Syarif Kasim II – Pekanbaru 12. EI Tari - Kupang 24. Kijang – Tanjung Pinang B. Pelabuhan Laut dan Pelabuahn Sungai : 1. Malahayati/Krueng Raya-Banda Aceh 31. 2. Sabang – Sabang 32. Waingapu - Waingapu 3. Lhokseumawe – Lhokseumawe 33. Pontianak- Pontianak 4. Meulaboh – Meulaboh 34. Banjarmasin – Banjarmasin 5. Sinabang – Sinabang 35. Balikpapan – Balikpapan 6. Tj Balai Asahan – Tj Balai Asahan 36. Lingkas- Tarakan 7. Belawan – Medan 37. Samarinda – Samarinda 8. Sibolga – Sibolga 38. Nunukan – Nunukan 9. Teluk Bayur – Padang 39. Sebatik – Sebatik 10. Dumai – Bengkalis 40. Bontang – Bontang 11. Pekanbaru – Pekanbaru 41. Makassar – Makassar 12. Tanjung Pinang – Tanjung Pinang 42. Malili – Ujung Pandang 13. Batu Ampar – Batam 43. Pare – Pare 14. Sekupang – Batam 44. Nusantara – Kendari 15. Tj Balai Karimun-Tj Balai Karimun 45. Pantoloan –Pantoloan 16. Lagoi – Lagoi 46. Ambon – Ambon 17. Panjang – Bandar Lampung 47.