Aftennatb.:Ofassisi • • • • • •• Dom Ermin Vitry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper for Tivoli

Edinburgh Research Explorer Giovanni Maria Nanino and the Roman confraternities of his time Citation for published version: O'Regan, N 2008, Giovanni Maria Nanino and the Roman confraternities of his time. in G Monari & F Vizzacarro (eds), Atti e memorie della Società Tibertina di storia e d’arte: Atti della Giornata internazionale di studio, Tivoli, 26 October 2007. vol. 31, Tivoli, pp. 113-127. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Atti e memorie della Società Tibertina di storia e d’arte Publisher Rights Statement: © O'Regan, N. (2008). Giovanni Maria Nanino and the Roman confraternities of his time. In G. Monari, & F. Vizzacarro (Eds.), Atti e memorie della Società Tibertina di storia e d’arte: Atti della Giornata internazionale di studio, Tivoli, 26 October 2007. (Vol. 31, pp. 113-127). Tivoli. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 GIOVANNI MARIA NANINO AND THE ROMAN CONFRATERNITIES OF HIS TIME NOEL O’REGAN, The University of Edinburgh Giovanni Maria Nanino was employed successively by three of Rome’s major institutions: S. -

Download/Autori C/ Rmcastagnetti-Bonifica.Pdf)

QUELLEN UND FORSCHUNGEN AUS ITALIENISCHEN ARCHIVEN UND BIBLIOTHEKEN BAND 93 QFIAB 93 (2013) QFIAB 93 (2013) QUELLEN UND FORSCHUNGEN AUS ITALIENISCHEN ARCHIVEN UND BIBLIOTHEKEN HERAUSGEGEBEN VOM DEUTSCHEN HISTORISCHEN INSTITUT IN ROM BAND 93 DE GRUYTER QFIAB 93 (2013) Redaktion: Alexander Koller Deutsches Historisches Institut in Rom Via Aurelia Antica 391 00165 Roma Italien http://www.dhi-roma.it ISSN 0079-9068 e-ISSN 1865-8865 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2014 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Druck: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ? Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com QFIAB 93 (2013) V INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Jahresbericht 2012 .................. VII–LXIII Michael Borgolte, Carlo Magno e la sua colloca- zione nella storia globale . ............... 1–26 Marco Leonardi, Gentile Stefaneschi Romano O. P. (†1303) o Gentile Orsini? Il caso singolare di un Domenicano nel Regnum Siciliae tra ricostruzione storica e trasmissione onomastica .......... 27–48 Brigide Schwarz, Die Karriere Leon Battista Alber- tis in der päpstlichen Kanzlei . .......... 49–103 Christiane Schuchard, Die Rota-Notare aus den Diözesen des deutschen Sprachraums 1471–1527. Ein biographisches Verzeichnis . .......... 104–210 Heinz Schilling, Lutero 2017. Problemi con la sua biografia . ....................... 211–225 Andrea Vanni, Die „zweite“ Gründung des Theati- nerordens . ....................... 226–250 Alessia Ceccarelli, Tra sovranità e imperialità. Genova nell’età delle congiure popolari barocche (1623–1637) ....................... 251–282 Nicola D’Elia, Bottais Bericht an den Duce über seine Deutschlandreise vom September 1933 . -

Sistina Crux Ebooklet Th19011

O CRUX BENEDICTA LENT AND HOLY WEEK AT THE SISTINE CHAPEL SISTINE CHAPEL CHOIR | MASSIMO PALOMBELLA O CRUX BENEDICTA LENT AND HOLY WEEK AT THE SISTINE CHAPEL SISTINE CHAPEL CHOIR | MASSIMO PALOMBELLA Palestrina: Popule meus (Chorus I) 2 ASH WEDNESDAY HOLY WEEK GREGORIAN CHANT GIOVANNI PIERLUIGI DA PALESTRINA A Entrance Antiphon: Misereris omnium, Domine 4:30 G Hymn: Vexilla regis prodeunt 7:40 Soloist: Cezary Arkadiusz Stoch Cantus; Altus I; Altus II; Tenor; Bassus Gregorian intonation: Roberto Zangari GABRIEL GÁLVEZ (c 1510–1578) Soloists verse 5: Stefano Guadagnini (Cantus); Enrico Torre (Altus); Roberto Zangari (Tenor) B Responsory: Emendemus in melius 3:24 Cantus; Altus; Tenor I; Tenor II; Bassus ORLANDO DI LASSO (c 1532–1594) H Antiphon: Ave Regina caelorum 1:35 GIOVANNI PIERLUIGI DA PALESTRINA (c 1525–1594) Cantus; Altus; Tenor; Bassus C Offertory Antiphon: Exaltabo te, Domine 2:11 Cantus; Altus; Tenor; Bassus; Quintus THE CHRISM MASS D Hymn: Audi, benigne Conditor 4:28 ANON. (attr. GIOVANNI PIERLUIGI DA PALESTRINA) Cantus; Altus; Tenor I; Tenor II; Bassus I Hymn: O Redemptor 1:35 Gregorian intonation: Marco Severin Cantus; Altus; Tenor; Bassus PALM SUNDAY HOLY THURSDAY: THE LORD’S SUPPER FRANCESCO SORIANO (1548/9–1621) GIOVANNI PIERLUIGI DA PALESTRINA E Hymn: Gloria, laus et honor 1:24 J Antiphon: O sacrum convivium 3:18 Cantus; Altus; Tenor; Bassus Cantus; Altus; Tenor; Bassus; Quintus GIOVANNI PIERLUIGI DA PALESTRINA GOOD FRIDAY F Antiphon: Pueri Hebraeorum 5:18 COSTANZO FESTA (c 1490–1545) Cantus; Altus; Tenor; Bassus K Psalm: -

Sacred Music Volume 118 Number 3

SACRED MUSIC (Fall) 1991 Volume 118, Number 3 Vienna. St. Michael s Church and Square SACRED MUSIC Volume 118, Number 3, Fall 1991 FROM THE EDITORS What is Sacred Music? 4 Sacred Music and the Liturgical Year 5 HOW AND HOW NOT TO SAY MASS 7 Deryck Hanshell, S.J. PALESTRINA 13 Karl Gustav Fellerer INAUGURATING A NEW BASILICA 21 Duane L. C. M. Galles REVIEWS 27 NEWS 28 CONTRIBUTORS 28 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publications: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103. Editorial Board: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, Editor Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Rev. John Buchanan Harold Hughesdon William P. Mahrt Virginia A. Schubert Cal Stepan Rev. Richard M. Hogan Mary Ellen Strapp Judy Labon News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Paul Salamunovich, 10828 Valley Spring Lane, N. Hollywood, Calif. 91602 Paul Manz, 1700 E. 56th St., Chicago, Illinois 60637 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Vice-President Gerhard Track General Secretary Virginia A. Schubert Treasurer Earl D. Hogan Directors Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Mrs. Donald G. Vellek William P. Mahrt Rev. Robert A. Skeris Membership in the CMAA includes a subscription to SACRED MUSIC. Voting membership, $12.50 annually; subscription membership, $10.00 annually; student membership, $5.00 annually. -

Cappella Sistina

Antwerpen, 22-30 augustus Inhoudstafel Woord vooraf | Philip Heylen 7 Laus Polyphoniae 2009 | Dag aan dag 10 Introductie | Bart Demuyt 23 Interview met Philippe Herreweghe 27 Essays De Spaanse furie in de pauselijke kapel 35 De Magistri Caeremoniarum, hoeders en beschermers van de rooms-katholieke liturgie 51 De Lage Landen in de pauselijke kapel 87 Muziekbronnen in het Vaticaan 103 Het Concilie van Trente 121 De Romeinse curie 137 De dagelijkse zangpraktijk in de pauselijke kapel 151 Muziek aan het hof van de Medici-pausen 171 Het groot Westers Schisma (1378-1417) 187 Rituelen bij overlijden en begrafenis van de paus 205 Virtuozen aan de pauselijke kapel 225 De architectuur van de Sixtijnse Kapel 241 Meerstemmige muziekpraktijk en repertoire van de Cappella Sistina 257 De paus en het muzikale scheppingsproces 271 De pausen in Avignon (1305-1377) 295 Van internationaal tot nationaal instituut: de Sixtijnse Kapel in de 17de eeuw 349 Decadentie en verval van de pauselijke kapel 379 Concerten Cursussen, lezing & interview 22/08/09 20.00 Collegium Vocale Gent 39 Polyfonie in de Sixtijnse Kapel, cursus polyfonie voor dummies 97 23.00 Capilla Flamenca & Psallentes 55 Cappella Sistina, themalezing 167 23/08/09 06.00 Capilla Flamenca & Psallentes 61 Philippe Herreweghe en de klassieke renaissancepolyfonie, interview 183 09.00 Capilla Flamenca & Psallentes 65 De Sixtijnse Kapel: geschiedenis, kunst en liturgie, cursus kunstgeschiedenis 221 12.00 Capilla Flamenca & Psallentes 69 Op bezoek bij de paus, muziekvakantie voor kinderen 291 15.00 Capilla -

Flickering of the Flame Exhibition Catalogue

FIS Reformation g14.qxp_Layout 1 2017-09-15 1:07 PM Page 1 FIS Reformation g14.qxp_Layout 1 2017-09-15 1:07 PM Page 2 FIS Reformation g14.qxp_Layout 1 2017-09-15 1:07 PM Page 3 Flickering of the Flame Print and the Reformation Exhibition and catalogue by Pearce J. Carefoote Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library 25 September – 20 December 2017 FIS Reformation g14.qxp_Layout 1 2017-09-15 1:07 PM Page 4 Catalogue and exhibition by Pearce J. Carefoote Editors Philip Oldfield & Marie Korey Exhibition designed and installed by Linda Joy Digital Photography by Paul Armstrong Catalogue designed by Stan Bevington Catalogue printed by Coach House Press Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Carefoote, Pearce J., 1961-, author, organizer Flickering of the flame : print and the Reformation / exhibition and catalogue by Pearce J. Carefoote. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library from September 25 to December 20, 2017. Includes bibliographical references. isbn 978-0-7727-6122-4 (softcover) 1. Printing—Europe—Influence—History—Exhibitions. 2. Books—Europe—History—Exhibitions. 3. Manuscripts—Europe—History—Exhibitions. 4. Reformation—Exhibitions. 5. Europe—Civilization—Exhibitions. I. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library issuing body, host institution II. Title. Z12.C37 2017 686.2'090902 C2017-902922-3 FIS Reformation g14.qxp_Layout 1 2017-09-15 1:07 PM Page 5 Foreword The year 2017 marks the five hundredth anniversary of the Reforma- tion, launched when Martin Luther penned and posted his Ninety- Five Theses to a church door in Wittenberg – or so the story goes. -

Programme, Haydn Probably Had the Toughest Upbringing

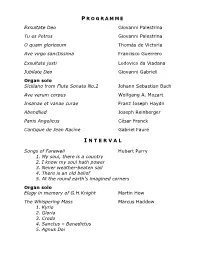

P ROGRAMME Exsultate Deo Giovanni Palestrina Tu es Petrus Giovanni Palestrina O quam gloriosum Thomás de Victoria Ave virgo sanctissima Francisco Guerrero Exsultate justi Lodovico da Viadana Jubilate Deo Giovanni Gabrieli Organ solo Siciliano from Flute Sonata No.2 Johann Sebastian Bach Ave verum corpus Wolfgang A. Mozart Insanae et vanae curae Franz Joseph Haydn Abendlied Joseph Reinberger Panis Angelicus César Franck Cantique de Jean Racine Gabriel Fauré I N T E R V A L Songs of Farewell Hubert Parry 1. My soul, there is a country 2. I know my soul hath power 3. Never weather-beaten sail 4. There is an old belief 5. At the round earth’s imagined corners Organ solo Elegy in memory of G.H.Knight Martin How The Whispering Mass Marcus Haddow 1. Kyrie 2. Gloria 3. Credo 4. Sanctus – Benedictus 5. Agnus Dei Two Motets Giovanni Palestrina (1525-1594) Palestrina’s life and work centred around Rome. He was born in the nearby town of Palestrina, from which he took his name, and his musical training began in Rome as a choirboy at the church of St Maria Maggiore. Over the years, his prodigious musical talents saw him appointed to a number of prominent posts within the Roman church. In 1551, while in his mid-twenties, he became maestro of the Cappella Giulia, the choir of St Peter’s Basilica. For a brief time, he was a member of the choir of the Sistine Chapel, until Pope Paul IV introduced a celibacy rule, and as a married man, Palestrina was dismissed. -

Tridentine Community News April 11, 2010

Tridentine Community News April 11, 2010 Music at the Vatican As a side note, Peter’s Way does not restrict itself to Vatican visits. Their impressive web site lists dozens of possible choir Holy Masses televised from the Vatican at Christmas and Easter performance tour options throughout Europe and North America. time invariably provoke conversations about the quality of the music provided at St. Peter’s Basilica. The general consensus is A Wedding at the Vatican that the choir members do not sing in unison, sound excessively operatic, and in general do not set a proper example of how Readers of this column are blessed to attend Holy Mass at one of professionally-sung liturgical music at the home base of Roman our beautiful historic churches. A wedding in any one of our Catholicism should sound. While the selection of music is quite churches is sure to be memorable and photogenic. But perhaps good, especially in recent years, the performance of it suffers. you’re up for a bigger challenge. You want to have your wedding at the ne plus ultra of churches, something you can talk about for The sound that we know from television is that of the Sistine the rest of your life. As with the choir situation, it’s easy if you Chapel Choir, which sings only for papal celebrations. In fairness, know the tricks of the trade. perhaps the mic’ing of this choir and the audio engineering is as responsible for what we hear as the singers themselves. You can arrange a wedding at St. -

Download Booklet

CORO The Sixteen Edition CORO The Essential Collection 2 CDs The Fairy Queen Handel: Dixit Dominus Henry Purcell (2 CD set) Steffani: Stabat Mater CORO The Sixteen Edition Based on Shakespeare's CORO The Sixteen Edition The Sixteen adds to 2 CDs A Midsummer Night's its stunning Handel Purcell Dream, The Fairy Queen Handel collection with a The Fairy Queen The Fairy Queen Dixit Dominus Ann Murray was composed in 1691/2 brand new recording The Lorna Anderson Gillian Fisher Steffani Michael Chance and remains without of his Dixit Dominus John Mark Ainsley Stabat Mater Ian Partridge Richard Suart doubt one of Purcell's set alongside a little Michael George The Sixteen greatest works adding his The Sixteen know treasure - harry christophers magic, wit and sensuality harry christophers Agostino Steffani’s Sixteen cor16005 to that of the play. cor16076 Stabat Mater. Compilation by: Robin Tyson - podiummusic.co.uk Re-mastering: Matt Howell (Floating Earth) Cover image: The Concert of Angels 1534-36, by Gaudenzio Ferrari (1474/80-1546) detail of fresco in the Sanctuary of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Saronno, Italy Sounds The Bridgeman Art Library Nationality/copyright status: Italian/out of copyright Design: Andrew Giles - [email protected] For further information about recordings on CORO or live performances and tours by Sublime The Sixteen, call +44 (0) 20 7488 2629 or email [email protected] 2009 The Sixteen Productions Ltd. The Voices of © 2009 The Sixteen Productions Ltd. Made in Great Britain The Sixteen To find out more about The Sixteen, concert tours, and to buy CDs visit HARRY CHRISTOPHERS www.thesixteen.com cor16073 Sounds Sublime The Sixteen The Definitive Collection CD1 CD2 1 J. -

GIULIA GALASSO a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of Birmingham City University for the Degree Of

THE MASS COLLECTION OCTO MISSAE (1663) BY FRANCESCO FOGGIA (1603-1688): AN ANALYTICAL STUDY AND CRITICAL EDITION GIULIA GALASSO A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Birmingham City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, The Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, Birmingham City University ABSTRACT Francesco Foggia (1603-1688) was one of the most prominent maestri di cappella of seventeenth-century Rome and an important mass composer. Historically, he has been regarded as one of the last heirs of Palestrina, largely due to the writings of Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni (1657-1743) and Giovanni Battista Martini (1706-1784). More recently, scholars have reassessed his style in his motets, psalms and oratorios. However, his mass style has received little rigorous scholarly attention. This is partly because of the scarcity of critical editions of his works. The present study presents critical editions of five of the masses from his Octo missae (Rome: Giacomo Fei, 1663). In conjunction with the three masses included in Stephen R. Miller‟s recent edition (2017), the entire volume is now available in full score. This enables an informed reassessment of Foggia‟s mass style. The present study analyses his use of features, such as time signatures, full choir and stile concertato, textures, thematic treatment and borrowing procedures. It compares Foggia‟s mass style with those of his predecessors, mainly Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c.1525-1594), Ruggero Giovannelli (c.1560-1625), near predecessor Gregorio Allegri (1582-1652) and contemporaries, Bonifatio Gratiani (1604/5-1664), Orazio Benevoli (1605-1672). -

TOC 0235 CD Booklet.Indd

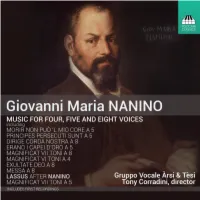

GIOVANNI MARIA NANINO, FORGOTTEN ROMAN MASTER by Maurizio Pastori and Michela Varvaro Giovanni Maria Nanino was one of the most important musicians in the Roman tradition of late-Renaissance polyphony, both as teacher and as composer, but the passage of time and the prominence of Palestrina have combined to cast him into obscurity. Nanino was born in Tivoli, north-east of Rome, in 1544, to a family originally from Vallerano in the province of Viterbo, rather further to the north-west. He probably sang as a child in the cappella of the cathedral in his home town and, afer spending some time in the service of Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (creator of the famous Villa d’Este in Tivoli), probably only in 1562, he sang in the Cappella Giulia in the Vatican (1566–68), and was later maestro di cappella in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore (1569–75) and the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi (1575–77). On 28 October 1577 he was admitted to the College of Papal Singers as a tenor and from 1580 his compositions entered the repertoire of the papal chapel; during his thirty years of activity there he was elected magister cappellae for at least three years (1598, 1604 and 1605, and perhaps also in 1597), his duties involving the management and representation of the College. Nanino took part in the cultural and musical life of late-Renaissance Rome, attending carefully to the mirabili concerti – sacred concerts for the period of Lent – which were held at Trinità dei Pellegrini; he was a singer and maestro di cappella of the music for several confraternities1 and took part in the creation of the Confraternita de’ musici di Roma sotto l’invocazione di Santa Cecilia, the original nucleus of the present Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. -

Renovatio Urbis

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository renovatio urbis Architecture, Urbanism and Ceremony in the Rome of Julius II Nicholas Temple 1 Agli amici di Antognano, Roma (Accademia Britannica) e Lincoln 2 Contents Illustration Credits Acknowledgements Introduction Chapter 1 - SIGN-POSTING PETER AND PAUL The Tiber’s Sacred Banks Peripheral Centres “inter duas metas” Papal Rivalries Chigi Chapel Chapter 2 - VIA GIULIA & PAPAL CORPORATISM The Politics of Order The Julian ‘Lapide’ Via Giulia The Legacy of Sixtus IV Quartière dei Banchi Via del Pellegrino, via Papale and via Recta Solenne Possesso and via Triumphalis Papal Corporatism Pons Neronianus and Porta Triumphalis Early Christian Precedents 3 Meta-Romuli and Serlio’s Scena Tragica Crossing Thresholds: Peter and Caesar The Papal ‘Hieroglyph’ and the Festa di Agone Chapter 3 - PALAZZO DEI TRIBUNALI and the Meaning of Justice sedes Iustitiae The Four Tribunals The Capitol and Communal/Cardinal’s Palace St Blaise and Justice Iustitia Cosmica Caesar and Iustitia pax Romana Chapter 4 – CORTILE DEL BELVEDERE, VIA DELLA LUNGARA and vita contemplativa “The Beautiful View” via suburbana/via sanctus Passage and Salvation Chapter 5 - ST. PETER’S BASILICA Orientation and Succession Transformations from Old to New Territorium Triumphale Sixtus IV and the Cappella del Coro Julius II and Caesar’s Ashes Janus and Peter 4 Janus Quadrifrons The Tegurium Chapter 6 - THE STANZA DELLA SEGNATURA A Testimony to a Golden Age Topographical and Geographical Connections in facultatibus Triune Symbolism Conversio St Bonaventure and the Itinerarium Mentis in Deum Justice and Poetry Mapping the Golden Age Conclusion - pons/facio: POPES AND BRIDGES The Julian ‘Project’ Pontifex Maximus Corpus Mysticum Raphael’s Portrait Notes Bibliography Index 5 Illustration Credits The author and publishers gratefully acknowledge the following for permission to reproduce images in the book.