Black's New Testament Commentary the Epistles of Peter and of Jude Jnd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

Interesting Facts About Jude.Pmd

InterestingInteresting FactsFacts AboutAbout JudeJude AUTHOR: Jude, one of the Lord’s brothers. • Wicked Sodom and Gomorrah TIME WRITTEN: Probable range: A.D. 66-80 I It appears that the purpose of the epistle of Jude was to: POSITION IN THE BIBLE: • 65th Book in the Bible • Condemn the practices of the ungodly libertines who were • 26th Book in the New Testament infesting and corrupting Christians. • 21st and last of 21 Epistle Books • To counsel the readers of the letter to: (Romans - Jude) - Stand firm. • Books to follow it. - Grow in their faith. CHAPTERS: 1 - Contend for the faith. VERSES: 25 WORDS: 613 I Jude alone refers to the dispute between Michael and the OBSERVATIONS ABOUT JUDE: devil about the body of Moses. 9 I Jude: I Jude’s benediction is one of the most beautiful in the Bible. • Was one of the Lord’s brothers. • Was called Judas in Matthew 13:55 and Mark 6:3 • The only other Biblical reference to him is in 1 Corinthians 9:5 where it is stated that “the brothers of the Lord” took their wives along on their missionary journeys. • It may be that the Judas of Acts 15;22, 32 may be another reference to him. • Judas and James are the only two of the Lord’s brothers to write books in the New Testament. “Beloved, while I was very diligent to write I Jude does not direct his epistle to: to you concerning our common salvation, • A stated circle of readers. • A stated geographical region. I found it necessary to write to you I At the beginning of the epistle, Jude focuses on the common salvation that Christians have, and then challenges exhorting you to contend earnestly for the them to contend for the faith. -

Citations in Classics and Ancient History

Citations in Classics and Ancient History The most common style in use in the field of Classical Studies is the author-date style, also known as Chicago 2, but MLA is also quite common and perfectly acceptable. Quick guides for each of MLA and Chicago 2 are readily available as PDF downloads. The Chicago Manual of Style Online offers a guide on their web-page: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html The Modern Language Association (MLA) does not, but many educational institutions post an MLA guide for free access. While a specific citation style should be followed carefully, none take into account the specific practices of Classical Studies. They are all (Chicago, MLA and others) perfectly suitable for citing most resources, but should not be followed for citing ancient Greek and Latin primary source material, including primary sources in translation. Citing Primary Sources: Every ancient text has its own unique system for locating content by numbers. For example, Homer's Iliad is divided into 24 Books (what we might now call chapters) and the lines of each Book are numbered from line 1. Herodotus' Histories is divided into nine Books and each of these Books is divided into Chapters and each chapter into line numbers. The purpose of such a system is that the Iliad, or any primary source, can be cited in any language and from any publication and always refer to the same passage. That is why we do not cite Herodotus page 66. Page 66 in what publication, in what edition? Very early in your textbook, Apodexis Historia, a passage from Herodotus is reproduced. -

Euripides” Johanna Hanink

The Life of the Author in the Letters of “Euripides” Johanna Hanink N 1694, Joshua Barnes, the eccentric British scholar (and poet) of Greek who the next year would become Regius Professor at the University of Cambridge, published his I 1 long-awaited Euripidis quae extant omnia. This was an enormous edition of Euripides’ works which contained every scrap of Euripidean material—dramatic, fragmentary, and biographical —that Barnes had managed to unearth.2 In the course of pre- paring the volume, Barnes had got wind that Richard Bentley believed that the epistles attributed by many ancient manu- scripts to Euripides were spurious; he therefore wrote to Bentley asking him to elucidate the grounds of his doubt. On 22 February 1693, Bentley returned a letter to Barnes in which he firmly declared that, with regard to the ancient epistles, “tis not Euripides himself that here discourseth, but a puny sophist that acts him.” Bentley did, however, recognize that convincing others of this would be a difficult task: “as for arguments to prove [the letters] spurious, perhaps there are none that will convince any person that doth not discover it by himself.”3 1 On the printing of the book and its early distribution see D. McKitterick, A History of Cambridge University Press I Printing and the Book Trade in Cambridge, 1534–1698 (Cambridge 1992) 380–392; on Joshua Barnes see K. L. Haugen, ODNB 3 (2004) 998–1001. 2 C. Collard, Tragedy, Euripides and Euripideans (Bristol 2007) 199–204, re- hearses a number of criticisms of Barnes’ methods, especially concerning his presentation of Euripidean fragments (for which he often gave no source, and which occasionally consisted of lines from the extant plays). -

On the Arrangement of the Platonic Dialogues

Ryan C. Fowler 25th Hour On the Arrangement of the Platonic Dialogues I. Thrasyllus a. Diogenes Laertius (D.L.), Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 3.56: “But, just as long ago in tragedy the chorus was the only actor, and afterwards, in order to give the chorus breathing space, Thespis devised a single actor, Aeschylus a second, Sophocles a third, and thus tragedy was completed, so too with philosophy: in early times it discoursed on one subject only, namely physics, then Socrates added the second subject, ethics, and Plato the third, dialectics, and so brought philosophy to perfection. Thrasyllus says that he [Plato] published his dialogues in tetralogies, like those of the tragic poets. Thus they contended with four plays at the Dionysia, the Lenaea, the Panathenaea and the festival of Chytri. Of the four plays the last was a satiric drama; and the four together were called a tetralogy.” b. Characters or types of dialogues (D.L. 3.49): 1. instructive (ὑφηγητικός) A. theoretical (θεωρηµατικόν) a. physical (φυσικόν) b. logical (λογικόν) B. practical (πρακτικόν) a. ethical (ἠθικόν) b. political (πολιτικόν) 2. investigative (ζητητικός) A. training the mind (γυµναστικός) a. obstetrical (µαιευτικός) b. tentative (πειραστικός) B. victory in controversy (ἀγωνιστικός) a. critical (ἐνδεικτικός) b. subversive (ἀνατρεπτικός) c. Thrasyllan categories of the dialogues (D.L. 3.50-1): Physics: Timaeus Logic: Statesman, Cratylus, Parmenides, and Sophist Ethics: Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Symposium, Menexenus, Clitophon, the Letters, Philebus, Hipparchus, Rivals Politics: Republic, the Laws, Minos, Epinomis, Atlantis Obstetrics: Alcibiades 1 and 2, Theages, Lysis, Laches Tentative: Euthyphro, Meno, Io, Charmides and Theaetetus Critical: Protagoras Subversive: Euthydemus, Gorgias, and Hippias 1 and 2 :1 d. -

The General Epistle of Jude

Jude 1 1 Jude 11 THE GENERAL EPISTLE OF JUDE 1 Jude, the servant of Jesus Christ, and brother of James, to them that are sanctified by God the Father, and preserved in Jesus Christ, and called: 2 Mercy unto you, and peace, and love, be multiplied. 3 Beloved, when I gave all diligence to write unto you of the common salvation, it was needful for me to write unto you, and exhort you that ye should earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints. 4 For there are certain men crept in unawares, who were before of old ordained to this condemnation, ungodly men, turning the grace of our God into lasciviousness, and denying the only Lord God, and our Lord Jesus Christ. 5 I will therefore put you in remembrance, though ye once knew this, how that the Lord, having saved the people out of the land of Egypt, afterward destroyed them that believed not. 6 And the angels which kept not their first estate, but left their own habitation, he hath reserved in everlasting chains under darkness unto the judgment of the great day. 7 Even as Sodom and Gomorrha, and the cities about them in like manner, giving themselves over to fornication, and going after strange flesh, are set forth for an example, suffering the vengeance of eternal fire. 8 Likewise also these filthy dreamers defile the flesh, despise dominion, and speak evil of dignities. 9 Yet Michael the archangel, when contending with the devil he disputed about the body of Moses, durst not bring against him a railing accusation, but said, The Lord rebuke thee. -

Ushaw the UNITY of SECOND PETER

THE UNITY OF SECOND PETER: A RECONSIDERATION our Lord's crucifixion a week later was to be a royal enthronement, a 'lifting up'; and, like the cruciftxion, it drew all men to him: , See,' the priests complain, ' the whole world goes after him.' There, then, John lays before us the life of Christ in its innermost significance. It is limidessly full of meaning. It is not the story pathetic, exciting, edifying-of a great man. It is for all men, for us each day as for the Jews then, a challenge and an appeal, a call to pass judgment: can we see him for what he is? can we see that Jesus is the Christ-that in these historical events the full meaning of life is contained? It is very literally a crucial test; and on the issue depends life or death for each of us. These things are written in order that we may believe, and believing have life in his name. L. JOHNSTON Ushaw THE UNITY OF SECOND PETER: A RECONSIDERATION THERE is no book in the New Testament that indicates its author so clearly as does the Second Episde of Saint Peter. He is Simeon Peter a servant and Aposde of Jesus Christ (I:I); a beloved brother of St Paul (3:I5). With others he was an eyewitness of the Transftgura tion on 'the Holy Mount' (I :I6-I8). His death was foretold by the Lord (I :I3ff.; c£ John 2I :I8ff.). Yet the authenticity of no New Testament writing is in such doubt, perhaps, as that of 2 Peter. -

Myth Matters: Intelligent Imagination in Plato's Phaedo and Phaedrus

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-01-10 Myth Matters: Intelligent Imagination in Plato's Phaedo and Phaedrus Kotow, Emily Claire Kotow, E. C. (2018). Myth Matters: Intelligent Imagination in Plato's Phaedo and Phaedrus. (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/5457 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/106376 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Myth Matters: Intelligent Imagination in Plato's Phaedo and Phaedrus by Emily Claire Kotow A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2018 ©Emily Claire Kotow 2018 Abstract This thesis examines the function of myth in Plato’s Phaedo and Phaedrus. Focusing on the afterlife of Phaedo, and the palinode of Phaedrus, I assert that Plato emphasizes the limits of understanding, and as a consequence, the need for intelligent imagination. Ultimately, myth serves to underscore the essential philosophical project of cultivating self-knowledge and therefore is an integral part of Plato’s philosophical project. ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank the Department of Religious Studies for all of the support it has given me over the many years that I have been studying at the University of Calgary. -

THE LETTER of JUDE's USE of 1 ENOCH: the BOOK of the WATCHERS AS SCRIPTURE LAWRENCE HENRY VANBEEK Submitted in Accordance with T

THE LETTER OF JUDE'S USE OF 1 ENOCH: THE BOOK OF THE WATCHERS AS SCRIPTURE by LAWRENCE HENRY VANBEEK submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject of NEW TESTAMENT at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: Professor J. E. BOTHA November 1997 I declare that The Letter ofJude's Use Of I Enoch: The Book Of The Watchers is my own work and that all of the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated or acknowledged by means of complete references. /f/ri.ll~ Lawrence Henry VanBeek Preface This thesis attempts to show that I Enoch: The Book of the Watchers (BW) was authoritative and therefore canonical literature for both the audience of Jude and for its author. To do this the possibility of some fluctuation in the third part of the canon until the end of the first century AD for groups outside of the Pharisees is examined; then three steps are taken showing that: I. Jubilees and the Qumran literature used BW and considered it authoritative. The Damascus Document and the Genesis Apocryphon both alluded to BW. Qumran also used Jubilees which used BW. 2. The New Testament used BW in several places. The most obvious places are Jude 6, 14 and 2 Peter 2: 4. Jude in particular used a quotation formula which other New Testament passages used to introduce authoritative literature. 3. The Apostolic and Church Fathers recognized that Jude used BW authoritatively. The final chapter deals with the specific arguments of R. -

The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church

Anke Wanger THE-733 1 Student Name: ANKE WANGER Student Country: ETHIOPIA Program: MTH Course Code or Name: THE-733 This paper uses [x] US or [ ] UK standards for spelling and punctuation The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church 1) Introduction The topic of Biblical canon formation is a wide one, and has received increased attention in the last few decades, as many ancient manuscripts have been discovered, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the question arose as to whether the composition of the current Biblical canon(s) should be re-evaluated based on these and other findings. Not that the question had actually been settled before, as can be observed from the various Church councils throughout the last two thousand years with their decisions, and the fact that different Christian denominations often have very different books included in their Biblical Canons. Even Churches who are in communion with each other disagree over the question of which books belong in the Holy Bible. One Church which occupies a unique position in this regard is the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church. Currently, it is the only Church whose Bible is comprised of Anke Wanger THE-733 2 81 Books in total, 46 in the Old Testament, and 35 in the New Testament.1 It is also the biggest Bible, according to the number of books: Protestant Bibles usually contain 66 books, Roman Catholic Bibles 73, and Eastern Orthodox Bibles have around 76 books, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on their belonging to the Greek Orthodox, Slavonic Orthodox, or Georgian -

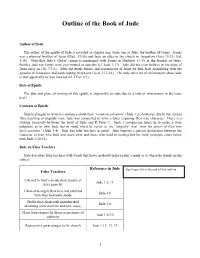

Outline of the Book of Jude

Outline of the Book of Jude Author of Book The author of the epistle of Jude is revealed in chapter one, verse one as Jude: the brother of James. James was a physical brother of Jesus (Matt. 13:55) and later an elder in the church in Jerusalem (Acts 15:13; Gal. 1:18). Note that Jude’s (Judas’) name is mentioned with James in Matthew 13:55 as the brother of Jesus. Neither Jude nor James were ever named as apostles (cf. Jude 1:17). Jude did not even believe in the deity of Jesus early on (Jn. 7:3-6). After the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus we find Jude assembling with the apostles in Jerusalem and participating in prayers (Acts 1:12-14). The only other bit of information about Jude is that apparently he was married (cf. I Cor. 9:5). Date of Epistle The date and place of writing of this epistle is impossible to state due to a lack of information in the letter itself. Contents of Epistle Jude had begun to write his audience about their “ common salvation ” (Jude 1:3); however, due to the current false teaching of ungodly men, Jude was compelled to write a letter exposing their true character. There is a striking similarity between the book of Jude and II Peter 2. Such a comparison helps us to make a clear judgment as to who Jude has in mind when he refers to the “ ungodly ” that “ turn the grace of God into lasciviousness” (Jude 1:4). Jude has false teachers in mind. -

Edmund Burke's German Readers at the End of Enlightenment, 1790-1815 Jonathan Allen Green Trinity Hall, University of Cambridg

Edmund Burke’s German Readers at the End of Enlightenment, 1790-1815 Jonathan Allen Green Trinity Hall, University of Cambridge September 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaborations except as declared in the Declaration and specified in the text. All translations, unless otherwise noted or published in anthologies, are my own. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University of similar institution except as declared in the Declaration and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Declaration and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the Faculty of History Degree Committee (80,000 words). Statement of Word Count: This dissertation comprises 79,363 words. 1 Acknowledgements Writing this dissertation was a challenge, and I am immensely grateful to the many friends and colleagues who helped me see it to completion. Thanks first of all are due to William O’Reilly, who supervised the start of this research during my MPhil in Political Thought and Intellectual History (2012-2013), and Christopher Meckstroth, who subsequently oversaw my work on this thesis.