Ushaw the UNITY of SECOND PETER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interesting Facts About Jude.Pmd

InterestingInteresting FactsFacts AboutAbout JudeJude AUTHOR: Jude, one of the Lord’s brothers. • Wicked Sodom and Gomorrah TIME WRITTEN: Probable range: A.D. 66-80 I It appears that the purpose of the epistle of Jude was to: POSITION IN THE BIBLE: • 65th Book in the Bible • Condemn the practices of the ungodly libertines who were • 26th Book in the New Testament infesting and corrupting Christians. • 21st and last of 21 Epistle Books • To counsel the readers of the letter to: (Romans - Jude) - Stand firm. • Books to follow it. - Grow in their faith. CHAPTERS: 1 - Contend for the faith. VERSES: 25 WORDS: 613 I Jude alone refers to the dispute between Michael and the OBSERVATIONS ABOUT JUDE: devil about the body of Moses. 9 I Jude: I Jude’s benediction is one of the most beautiful in the Bible. • Was one of the Lord’s brothers. • Was called Judas in Matthew 13:55 and Mark 6:3 • The only other Biblical reference to him is in 1 Corinthians 9:5 where it is stated that “the brothers of the Lord” took their wives along on their missionary journeys. • It may be that the Judas of Acts 15;22, 32 may be another reference to him. • Judas and James are the only two of the Lord’s brothers to write books in the New Testament. “Beloved, while I was very diligent to write I Jude does not direct his epistle to: to you concerning our common salvation, • A stated circle of readers. • A stated geographical region. I found it necessary to write to you I At the beginning of the epistle, Jude focuses on the common salvation that Christians have, and then challenges exhorting you to contend earnestly for the them to contend for the faith. -

The General Epistle of Jude

Jude 1 1 Jude 11 THE GENERAL EPISTLE OF JUDE 1 Jude, the servant of Jesus Christ, and brother of James, to them that are sanctified by God the Father, and preserved in Jesus Christ, and called: 2 Mercy unto you, and peace, and love, be multiplied. 3 Beloved, when I gave all diligence to write unto you of the common salvation, it was needful for me to write unto you, and exhort you that ye should earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints. 4 For there are certain men crept in unawares, who were before of old ordained to this condemnation, ungodly men, turning the grace of our God into lasciviousness, and denying the only Lord God, and our Lord Jesus Christ. 5 I will therefore put you in remembrance, though ye once knew this, how that the Lord, having saved the people out of the land of Egypt, afterward destroyed them that believed not. 6 And the angels which kept not their first estate, but left their own habitation, he hath reserved in everlasting chains under darkness unto the judgment of the great day. 7 Even as Sodom and Gomorrha, and the cities about them in like manner, giving themselves over to fornication, and going after strange flesh, are set forth for an example, suffering the vengeance of eternal fire. 8 Likewise also these filthy dreamers defile the flesh, despise dominion, and speak evil of dignities. 9 Yet Michael the archangel, when contending with the devil he disputed about the body of Moses, durst not bring against him a railing accusation, but said, The Lord rebuke thee. -

THE LETTER of JUDE's USE of 1 ENOCH: the BOOK of the WATCHERS AS SCRIPTURE LAWRENCE HENRY VANBEEK Submitted in Accordance with T

THE LETTER OF JUDE'S USE OF 1 ENOCH: THE BOOK OF THE WATCHERS AS SCRIPTURE by LAWRENCE HENRY VANBEEK submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject of NEW TESTAMENT at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: Professor J. E. BOTHA November 1997 I declare that The Letter ofJude's Use Of I Enoch: The Book Of The Watchers is my own work and that all of the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated or acknowledged by means of complete references. /f/ri.ll~ Lawrence Henry VanBeek Preface This thesis attempts to show that I Enoch: The Book of the Watchers (BW) was authoritative and therefore canonical literature for both the audience of Jude and for its author. To do this the possibility of some fluctuation in the third part of the canon until the end of the first century AD for groups outside of the Pharisees is examined; then three steps are taken showing that: I. Jubilees and the Qumran literature used BW and considered it authoritative. The Damascus Document and the Genesis Apocryphon both alluded to BW. Qumran also used Jubilees which used BW. 2. The New Testament used BW in several places. The most obvious places are Jude 6, 14 and 2 Peter 2: 4. Jude in particular used a quotation formula which other New Testament passages used to introduce authoritative literature. 3. The Apostolic and Church Fathers recognized that Jude used BW authoritatively. The final chapter deals with the specific arguments of R. -

The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church

Anke Wanger THE-733 1 Student Name: ANKE WANGER Student Country: ETHIOPIA Program: MTH Course Code or Name: THE-733 This paper uses [x] US or [ ] UK standards for spelling and punctuation The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church 1) Introduction The topic of Biblical canon formation is a wide one, and has received increased attention in the last few decades, as many ancient manuscripts have been discovered, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the question arose as to whether the composition of the current Biblical canon(s) should be re-evaluated based on these and other findings. Not that the question had actually been settled before, as can be observed from the various Church councils throughout the last two thousand years with their decisions, and the fact that different Christian denominations often have very different books included in their Biblical Canons. Even Churches who are in communion with each other disagree over the question of which books belong in the Holy Bible. One Church which occupies a unique position in this regard is the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church. Currently, it is the only Church whose Bible is comprised of Anke Wanger THE-733 2 81 Books in total, 46 in the Old Testament, and 35 in the New Testament.1 It is also the biggest Bible, according to the number of books: Protestant Bibles usually contain 66 books, Roman Catholic Bibles 73, and Eastern Orthodox Bibles have around 76 books, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on their belonging to the Greek Orthodox, Slavonic Orthodox, or Georgian -

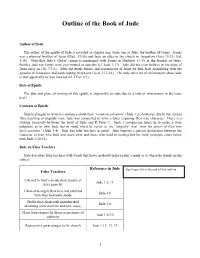

Outline of the Book of Jude

Outline of the Book of Jude Author of Book The author of the epistle of Jude is revealed in chapter one, verse one as Jude: the brother of James. James was a physical brother of Jesus (Matt. 13:55) and later an elder in the church in Jerusalem (Acts 15:13; Gal. 1:18). Note that Jude’s (Judas’) name is mentioned with James in Matthew 13:55 as the brother of Jesus. Neither Jude nor James were ever named as apostles (cf. Jude 1:17). Jude did not even believe in the deity of Jesus early on (Jn. 7:3-6). After the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus we find Jude assembling with the apostles in Jerusalem and participating in prayers (Acts 1:12-14). The only other bit of information about Jude is that apparently he was married (cf. I Cor. 9:5). Date of Epistle The date and place of writing of this epistle is impossible to state due to a lack of information in the letter itself. Contents of Epistle Jude had begun to write his audience about their “ common salvation ” (Jude 1:3); however, due to the current false teaching of ungodly men, Jude was compelled to write a letter exposing their true character. There is a striking similarity between the book of Jude and II Peter 2. Such a comparison helps us to make a clear judgment as to who Jude has in mind when he refers to the “ ungodly ” that “ turn the grace of God into lasciviousness” (Jude 1:4). Jude has false teachers in mind. -

The Epistle of Jude

The Epistle of Jude Table of Contents Introduction........................................................................................................2 Outline of the Epistle.........................................................................................3 Chapter 1..........................................................................................................5 This booklet prepared by Richard Thetford April 2006 www.thetfordcountry.com The Epistle of Jude 1 The Epistle of Jude Introduction Author The writer identifies himself as a “brother of James” (1). James was a leader in the Jerusalem church (Acts 15:13-21; Gal 1:19; 2:9). Since James was one of the brothers of Jesus, Jude was likewise one of His brothers (Matt 13:55; Mark 6:3). “Judas” in both places in the NIV indicates that Jesus had a brother by that name. Six other Judes or Judases are referred to in the New Testament, but the writer of this epistle is not to be confused with any of them. He differentiated himself from others of the same name by the mention of his brother, rather than his father. Jude was not an apostle, as indicated by the omission of the apostolic title. Almost nothing is known about the life of Jude. He was apparently convinced of the deity of Christ after the resurrection. The Recipients of the Letter A comparison of this epistle with the Second Epistle of Peter indicates they were addressed to Christians in general with a common problem. Peter predicted that false teachers would come (2 Pet 2:1-3), Jude says they have already come (4, 8, 10-13, 16). The readers are to remember what the apostles had said about “scoffers” (compare vs 18 with 2 Pet 3:3). Jude emphasizes the importance of “contending for the faith” (3). -

Jude's Use of the Pseudepigraphal Book of 1 Enoch

Jude's Use of the Pseudepigraphal Book of 1 Enoch Cory D. Anderson IT HAS BEEN RIGHTLY STATED that the Epistle of Jude is the most neglected book in the New Testament.1 Such an assertion was made in 1975 by Douglas Rowston, who noticed that, "[w]ith the exception of G. B Stevens, New Testament theologians have ignored the book and, apart from Friedrich Spitta and J. B. Mayor, modern New Testament scholars have not treated the book except in a series of commentaries."2 Since Rowston's provoking comments twenty-six years ago, a plethora of articles and new commentaries have been produced.3 Unfor- 1. Douglas J. Rowston, "The Most Neglected Book In The New Testament." New Tes- tament Studies 21 (July 1975): 554. This observation was made first by William Barclay in 1960 (William Barclay, The Letters of John and Jude [Edinburgh, Scotland: The Saint Andrew Press], 183). 2. Rowston, "Most Neglected Book," 554. 3. For recent articles and commentaries on the epistle of Jude see: Richard J. Bauck- ham, Word Biblical Commentary: Jude, 2 Peter (Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1983); J. Daryl Charles, " 'Those' and 'These.' The use of the Old Testament in The Epistle of Jude," Journal for the Study of the New Testament 38 (February 1990): 109-124; J. Daryl Charles, "Jude's Use of Pseudepigraphical Source Material as Part of a Literary Strategy," New Testament Studies 37, no. 1 (January 1991): 130-145; J. Daryl Charles, "Literary Artifice in the Epistle of Jude," Zeitschrift fur die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der alteren Kirche 82, no. -

Notes on Introduction

Notes on Jude 2003 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Traditionally the writer of this epistle was Judas, the half-brother of Jesus Christ (Matt. 13:55; Mark 6:3) and the brother of James (Jude 1; Acts 15:13). Some scholars have challenged this identification in recent years, but they have not proved it incorrect. As such, Jude (Gr. Judas, Heb. Judah, "praise") was a Jewish Christian. Like James he was a Hellenized Galilean Jew who wrote with a cultivated Greek style.1 Jesus' physical brothers did not believe in Him while He was ministering (John 7:5). James became a believer after Jesus' resurrection (1 Cor. 15:7), and we may assume that Jude did too. Jesus' brothers were part of the praying group that awaited the coming of the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:14). They were well known in the early church (1 Cor. 9:5). Jude's many allusions to the Old Testament suggest that his original readers were very familiar with it. While this could have been true of any Christians, it would have been particularly true of Jewish Christians. Consequently many commentators believe Jude addressed this epistle to Jewish Christians primarily. ". we should not see it as a 'catholic letter' addressed to all Christians, but as a work written with a specific, localized audience in mind."2 "A predominantly, but not exclusively, Jewish Christian community in a Gentile society seems to account best for what little we can gather about the recipients of Jude's letter."3 The time of writing is very difficult to ascertain. -

God's Word Is His Revealed, Written, and Complete Revelation

WCF2 Proposition: God’s Word is His revealed, written, and complete revelation. II. Under the name of Holy Scripture, or the Word of God written, are now contained all the books of the Old and New Testament, which are these: Of the Old Testament: Of the New Testament: Genesis The Gospels according to Ecclesiastes The Epistle to the Hebrews Exodus Matthew The Song of The Epistle of James Leviticus Mark Songs Numbers Luke Isaiah The Epistles of Peter Deuteronomy John Jeremiah I Peter Joshua The Acts of the Apostles Lamentations II Peter Judges Ezekiel Ruth Paul's Epistles to Daniel The Epistles of John I Samuel Romans Hosea I John II Samuel I Corinthians Joel II John I Kings II Corinthians Amos III John II Kings Galatians Obadiah I Chronicles Ephesians Jonah The Epistle of Jude II Chronicles Philippians Micah Ezra Colossians Nahum The Revelation of John Nehemiah I Thessalonians Habakkuk Esther II Thessalonians Zephaniah Job Haggai I Timothy Psalms Zechariah II Timothy Proverbs Malachi Titus Philemon All which are given by inspiration of God to be the rule of faith and life.7 7 Luke 16:29 Abraham saith unto him, They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them. 31 And he said unto him, If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded, though one rose from the dead. Ephesians 2:20 And are built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ himself being the chief corner stone. Revelation 22:18 For I testify unto every man that heareth the words of the prophecy of this book, If any man shall add unto these things, God shall add unto him the plagues that are written in this book: 19 And if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book. -

A Brief Study Author: in Jude 1 the Auth

A Brief Study on the Epistle of Jude, Page 1 The Epistle of St. Jude to the Church – A Brief Study Author: In Jude 1 the author identifies himself as “Jude, of Jesus Christ servant, and brother of James.” A more specific identification is not offered. Clearly Jude is well enough known to the original recipients of the epistle that no further introduction was necessary. The name Jude or Judas is derived from the name of the fourth son of Jacob by Leah, who also gave his name to the tribe of Israelites (hd'Why> Genesis 35:23), through whom the Messiah was to come (Genesis 49:8-12, Matthew 1:2-3) In the Greek the name is VIou,daj, which we would transliterate Judas. Judas was a common name in Palestine in the first century. Five prominent men in the New Testament bear the name Judas. The first is Judas Iscariot, the betrayer, who dies in the Gospel account of St. Matthew (Matthew 27:5; Acts 1:15-20). The second is Barsabbas, a believer, who was one of four to carry the written dictates of the first Apostolic council, and had been suggested as a replacement for Stephen (Acts 15:22, Acts 1:23). The third is Judas, the brother of Jesus Christ (Matthew 13:54-56; Mark 6:3). The fourth is Judas the Galilean, who led a revolt and was killed (Acts 5:37). The last is Judas son of James, one of the Twelve (Luke 6:12-16, Acts 1:13). Of these men, the only one matches the description “Jude … brother of James”: the third, Judas, the brother of Jesus. -

How the Epistle of Jude Illustrates Gnostic Ties with Jewish Apocalypticism Through Early Christianity

JUDE IN THE MIDDLE: HOW THE EPISTLE OF JUDE ILLUSTRATES GNOSTIC TIES WITH JEWISH APOCALYPTICISM THROUGH EARLY CHRISTIANITY _______________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY _______________________________________________________ by Boyd A. Hannold May, 2009 i ABSTRACT Jude in the Middle: How the Epistle of Jude Illustrates Gnostic Ties with Jewish Apocalypticism through Early Christianity Boyd A. Hannold Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Vasiliki Limberis Ph.D. In the mid 1990’s, Aarhus University's Per Bilde detailed a new hypothesis of how Judaism, Christianity and Gnosticism were connected. Bilde suggested that Christianity acted as a catalyst, propelling Jewish Apocalypticism into Gnosticism. This dissertation applies the epistle of Jude to Per Bilde’s theory. Although Bilde is not the first to posit Judaism as a factor in the emergence of Gnosticism, his theory is unique in attempting to frame that connection in terms of a religious continuum. Jewish Apocalypticism, early Christianity, and Gnosticism represent three stages in a continual religio-historical development in which Gnosticism became the logical conclusion. I propose that Bilde is essentially correct and that the epistle of Jude is written evidence that the author of the epistle experiences the phenomena. The author of Jude (from this point on referred to as Jude) sits in the middle of Bilde’s progression and may be the most perceptive of New Testament writers in responding to the crisis. He looks behind to see the Jewish association with the Christ followers and seeks to maintain it. -

Notes on Introduction

Notes on Jude 2015 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction HISTORICAL BACKGROUND According to tradition, the writer of this epistle was "Judas" (Jude), who was both the half-brother of Jesus Christ (Matt. 13:55; Mark 6:3) and a brother of James, the leader of the Jerusalem church (Jude 1; Acts 15:13). Some scholars have challenged this identification in recent years, but they have not proved it incorrect.1 As such, Jude (Gr. Judas, Heb. Judah, "praise") was a Jewish Christian. Like James, he was a Hellenized Galilean Jew who wrote with a cultivated Greek style. As we might expect, Jude normally alluded to the Hebrew Scriptures rather than to the Septuagint, unlike many of the New Testament writers. Jesus' physical brothers did not believe in Him while He was ministering (John 7:5). James became a believer after Jesus' resurrection (1 Cor. 15:7), and we may assume that Jude did too.2 Jesus' brothers were part of the praying group that awaited the coming of the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:14). They were well known in the early church (1 Cor. 9:5). Jude's many allusions to the Old Testament suggest that his original readers were very familiar with it. While this could have been true of many Christians, it would have been particularly true of Jewish Christians. Consequently many commentators believe Jude addressed this epistle primarily to Jewish Christians. ". we should not see it as a 'catholic letter' addressed to all Christians, but as a work written with a specific, localized audience in mind."3 "A predominantly, but not exclusively, Jewish Christian community in a Gentile society seems to account best for what little we can gather about the recipients of Jude's letter."4 The time of writing is very difficult to ascertain.