For Immediate Release: 5:00Am Aug 7, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kings Lake From: Utah Place Names

Kings Lake from: Utah Place Names KINGS LAKE (Duchesne County) is in the central Uinta Mountains on the southwest slopes of Kings Peak. See the peak below for name source. >T4N,R4W,USM; 11,416' (3,480m). KINGS PEAK (Duchesne County) is in the south central section of the Uinta Mountains between the headwaters of the Uinta and Yellowstone rivers. Kings Peak is the highest point in Utah. The peak was named for Clarence King, an early director of the U.S. Geological Survey. >13,528' (4,123m). Bibliography: Layton, Stanford J. "Fort Rawlins, Utah: A Question of Mission and Means." Utah Historical Quarterly 42 (Winter 1974): 68-83. Marsell, Ray E. "Landscapes of the North Slopes of the Uinta Mountains." A Geological Guidebook of the Uinta Mountains, 1969. Utah's Geography and Counties. Salt Lake City: Author, 1967. Stegner, Wallace. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1954.Utah, A Guide to the State. Work Projects Administration. Comp. by Utah State Institute of Fine Arts, Salt Lake County Commission. New York: Hastings House, 1941. U.S. Board on Geographic Names, Decision List, No. 6602. EXPLANATION OF SYMBOLS... 1. An asterisk (*) following a place name indicates past or present inhabitation. 2. When a series of letters and numbers are present towards the end of an entry after the ">" symbol, the first group indicates section/township/range as closely as can be pinpointed (i.e., S12,T3S,R4W,SLM, or USM). A section equals approximately one square mile, reflecting U.S. Geological Survey topographic map sections. Because Utah is not completely mapped, some entries are incomplete. -

Eriophorum Scheuchzeri Hoppe (White Cottongrass): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Eriophorum scheuchzeri Hoppe (white cottongrass): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project March 2, 2006 Juanita A. R. Ladyman, Ph.D. JnJ Associates LLC 6760 S. Kit Carson Circle East Centennial, CO 80122 Peer Review Administered by Society of Conservation Biology Ladyman, J.A.R. (2006, March 2). Eriophorum scheuchzeri Hoppe (white cottongrass): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/ projects/scp/assessments/eriophorumscheuchzeri.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The time spent and help given by all the people and institutions mentioned in the reference section are gratefully acknowledged. I value the information provided by Jacques Cayouette, with Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, and thank him for his help. I also appreciate the access to files and the assistance given to me by Andrew Kratz, USDA Forest Service Region 2, and Chuck Davis, US Fish and Wildlife Service, both in Denver, Colorado. The information sent from Bonnie Heidel, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database; Teresa Prendusi, USDA Forest Service Region 4; Thomas A. Zanoni, New York Botanical Garden; Rusty Russell, United States National Herbarium; Ronald Hartman and Joy Handley, Rocky Mountain Herbarium at the University of Wyoming; Alan Batten, University of Alaska Museum of the North; Mary Barkworth and Michael Piep, the Intermountain Herbarium; Jennifer Penny and Marta Donovan, British Columbia Conservation Data Centre; John Rintoul, Alberta Natural Heritage Information Center; and Ann Kelsey, Garrett Herbarium, are also very much appreciated. I would also like to thank Deb Golanty, Helen Fowler Library at Denver Botanic Gardens, for her persistence in retrieving some rather obscure articles. -

Interpreting the Timberline: an Aid to Help Park Naturalists to Acquaint Visitors with the Subalpine-Alpine Ecotone of Western North America

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1966 Interpreting the timberline: An aid to help park naturalists to acquaint visitors with the subalpine-alpine ecotone of western North America Stephen Arno The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Arno, Stephen, "Interpreting the timberline: An aid to help park naturalists to acquaint visitors with the subalpine-alpine ecotone of western North America" (1966). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6617. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6617 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEKFRETING THE TIMBERLINE: An Aid to Help Park Naturalists to Acquaint Visitors with the Subalpine-Alpine Ecotone of Western North America By Stephen F. Arno B. S. in Forest Management, Washington State University, 196$ Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Forestry UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1966 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners bean. Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP37418 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

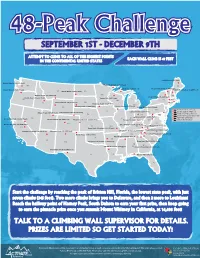

PRINT 48-Peak Challenge

48-Peak Challenge SEPTEMBER 1ST - DECEMBER 9TH ATTEMPT TO CLIMB TO ALL OF THE HIGHEST POINTS EACH WALL CLIMB IS 47 FEET IN THE CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES Katahdin (5,268 feet) Mount Rainier (14,411 feet) WA Eagle Mountain (2,301 feet) ME Mount Arvon (1,978 feet) Mount Mansfield (4,393 feet) Mount Hood (11,239 feet) Mount Washington (6,288 feet) MT White Butte (3,506 feet) ND VT MN Granite Peak (12,799 feet) NH Mount Marcy (5,344 feet) Borah Peak (12,662 feet) OR Timms Hill (1,951 feet) WI NY MA ID Gannett Peak (13,804 feet) SD CT Hawkeye Point (1,670 feet) RI MI Charles Mount (1,235 feet) WY Harney Peak (7,242 feet) Mount Davis (3,213 feet) PA CT: Mount Frissell (2,372 feet) IA NJ DE: Ebright Azimuth (442 feet) Panorama Point (5,426 feet) Campbell Hill (1,549 feet) Kings Peak (13,528 feet) MA: Mount Greylock (3,487 feet) NE OH MD DE MD: Backbone Mountain (3360 feet) Spruce Knob (4,861 feet) NV IN NJ: High Point (1,803 feet) Boundary Peak (13,140 feet) IL Mount Elbert (14,433 feet) Mount Sunflower (4,039 feet) Hoosier Hill (1,257 feet) WV RI: Jerimoth Hill (812 feet) UT CO VA Mount Whitney (14,498 feet) Black Mountain (4,139 feet) KS Mount Rogers (5,729 feet) CA MO KY Taum Sauk Mountain (1,772 feet) Mount Mitchell (6,684 feet) Humphreys Peak (12,633 feet) Wheeler Peak (12,633 feet) Clingmans Dome (6,643 feet) NC Sassafras Mountain (3,554 feet) Black Mesa (4,973 feet) TN Woodall Mountain (806 Feet) OK AR SC AZ NM Magazine Mountain (2,753 feet) Brasstown Bald (4,784 feet) GA AL Driskill Mountain (535MS feet) Cheaha Mountain (2,405 feet) Guadalupe Peak (8,749 feet) TX LA Britton Hill (345 feet) FL Start the challenge by reaching the peak of Britton Hill, Florida, the lowest state peak, with just seven climbs (345 feet). -

National Geographic's National Conservation Lands 15Th

P ow ear Pt. Barr d B 5 ay Bellingham Ross Lake E ison Bay Harr PACIFIC NORT S HWES Cape Flattery t San Juan T N ra Islands AT i I LisburneCape N o t SAN JUAN ISLANDS ONAL S r t h S l o p e of CE P Ju N IC a NATIONAL MONUMENT T e F N 9058 ft KMt. Isto Cape Alava n R CANADA KCopper Butte n 61 m d A l . lvill 27 e a L B o e F I d F U.S. C u L 7135 ft t M o Central Arctic c o d R a 2175 m O K h i r l g Management o e r k k e O E Priest o a e 2 C Area G t d O 101 i L. e r K N l . A n S P S R l 95 as K i e r E a 93 Ma o ot Central Arctic a i p z a L i e l b Management KGlacier Pk. Lake E a 97 b W IS A 15 ue Mt. Olympus K l N r Area STEESE 10541 ft D S Chelan m o CANADA 7965 ft i 89 Cape Prince NATIONAL 3213 m C 2 u uk 2428 m 2 u n k Franklin D. l L Lake Elwell d CONSERVATION U.S. s A of Wales u r R R Roosevelt o K oy AREA Y Bureau of Land Management e C h K u L lle N I ei h AT 191 Seward k Lake 2 Or s ION IC TRAIL 2 o A d R 395 Pen i A O L. -

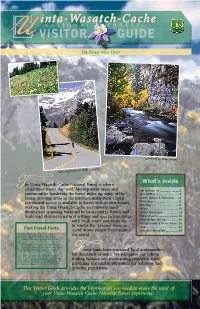

Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest Is Where Civilization Meets the “Wild.” Metropolitan Areas and Get to Know Us

inta-Wasatch-Cache NATIONAL FOREST U VISITOR GUIDE The Forest Next Door Logan River (© Mike Norton) Nebo Loop Road (© Willie Holdman) What’s Inside he Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest is where civilization meets the “wild.” Metropolitan areas and Get»to»Know»Us»......................... 2 Tcommunities bordering the forest make up some of the Special»Places»...........................3 fastest growing areas in the Intermountain West. Quick, Scenic»Byways»&»Backways»......4 convenient access is available to forest visitors year-round, Wilderness».................................6 Activities».................................... 8 making the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache an intensely used Hiking».......................................»10 destination spanning backyard to backcountry. Roads and Winter»Recreation....................»12 trails lead visitors to natural settings and spectacular vistas Flora»&»Fauna»..........................»14 with fresh water and clean air. Know»Before»You»Go.................16 Campgrounds»&»Picnic»Areas...18 In winter, the “Greatest Snow on Fast Forest Facts Maps»........................................»24 Earth” draws people from around Contact»Information»................»28 »» Size:»2.1»million»acres,»from» the world. desert»to»high»mountain»peaks.» »» The»oldest»exposed»rocks»in»Utah» can»be»seen»in»outcrops»near»the» mouth»of»Farmington»Canyon.» orest lands have sustained local communities »» The»Jardine»Juniper»tree»is»over» for thousands of years. We recognize our role in 1,500»years»old»and»is»one»of»the» F finding balance and maintaining relevance, while oldest»living»trees»in»the»Rocky» Mountains. providing sustainable recreation for a diverse and growing population. This Visitor Guide provides the information you need to make the most of your Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest experience. G et to Know Us History s “The Forest Next Door,” the Uinta-Wasatch- y the1890s many of the range and timber resources of ACache National Forest has long been sought after for its Bthe Uinta and Wasatch Mountains were seriously depleted. -

Comment on Recommended Wilderness!

Comment on Recommended Wilderness! A primer for writing your own comments to the Forest Service OVERVIEW The Salmon-Challis National Forest is the largest forest in the state, and contains some of its wildest remaining unroaded areas, such as the Lost River Range, Pioneer Mountains, and Lemhi Range. Forest planning is the process through which the Forest Service determines which areas have the highest and best wilderness value and thus should be considered by Congress for future conservation. The Forest Service would like to know if you think that any specific areas on the Salmon-Challis should be recommended for formal wilderness protection. Federally designated wilderness remains the gold standard for protecting wild places on our public lands! HOW YOU CAN HELP: SPEAK UP TODAY! If you have 5 minutes... Use the webmap commenting tool to write a quick comment linked to a particular area, or write a general comment in support of recommended wilderness through the ICL Take Action center. If you have 15 minutes... Write multiple comments through the webmap tool or a longer comment through the Take Action page where you share a meaningful experience you’ve had in the wilderness evaluation areas. If you have 30 minutes... Write a more detailed comment that shares personal stories and touches upon several areas under consideration for recommended wilderness. Submit via email ([email protected]). COMMENT WRITING TIPS ● Make it personal. Personal stories are more powerful because they show that you have a tangible connection to these places. Draw upon your own experiences to express why certain places are important to you and why they should be recommended as wilderness. -

ASHLEY National Forest

INTERMOUNTAIN REGION ASHLEY National Forest AT A GLANCE he Ashley National Forest is home to the highest peak in The Ashley National Forest spans the T Ute Mountain Lookout northeastern part of Utah (1,287,909 acres) and Utah, Kings Peak, and is best known Tower on the Ashley a portion of western Wyoming for the Flaming Gorge National National Forest was (96,223 acres). Recreation Area. It also includes the rededicated in 2014. Sheep Creek Geological Area, the High Uinta Wilderness Area, and the Green River. The Ashley sees many visitors from the Wasatch Front and Denver areas. ASHLEY NF Some discover it while en route from Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon via Highway 191. The Ashley National Forest provides numerous recreational trails for activities like hiking and cross- country skiing. Some are marked with interpretive signs to educate visitors about the Forest. Other trails lead to Wilderness areas or are designated for snowmobiling and TOTAL ACRES IN UTAH 90% OHV (off-highway vehicle) use. 1.4 M IN WYOMING 10% The Forest has emphasis areas in recreation, grazing, and timber. It has also focused on the issues of OHV management and stabilizing irrigation reservoirs in Wilderness areas. FOREST LANDSCAPE THE FOREST RECIEVES ABOUT The Ashley’s landscape ranges from high desert country to high mountain areas. 295 THOUSAND The elevation varies from about 6,000 to 13,528 feet above sea level at the summit VISITORS EACH YEAR of Kings Peak. The Forest provides healthy habitat for deer, elk, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, and trophy-sized trout. The Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, Green River, High Uintas Wilderness, and Sheep Creek National Geological Area are just some of the popular attractions. -

2019 Annual the ALPINE CLUB of CANADA

The Alpine Club of Canada • Vancouver Island Section Island Bushwhacker 2019 Annual THE ALPINE CLUB OF CANADA VANCOUVER ISLAND SECTION ISLAND BUSHWHACKER ANNUAL VOLUME 47 – 2019 Cover Image: Braiding the slopes at Hišimýawiƛ Opposite Page: Clarke Gourlay skiing at 5040 (Photo by Gary Croome) Mountain (see Page 16) (Photo by Chris Istace) VANCOUVER ISLAND SECTION OF THE ALPINE CLUB OF CANADA Section Executive 2019 Chair Catrin Brown Secretary David Lemon Treasurers Clarke Gourlay Garth Stewart National Rep Christine Fordham Education Alois Schonenberger Education Colin Mann Membership Kathy Kutzer Communication Brianna Coates Communication/Website Jes Scott Communication/Website Martin Hofmann Communication/Schedule Karun Thanjuvar Island Bushwhacker Annual Rob Macdonald Newsletter Mary Sanseverino Leadership Natasha Salway Member at Large Anya Reid Access and Environment Barb Baker Hišimýawiƛ (5040 Hut) Chris Jensen Equipment Mike Hubbard Kids and Youth Programme Derek Sou Summer Camp Liz Williams Library and Archives Tom Hall ACC VI Section Website: accvi.ca ACC National Website: alpineclubofcanada.ca ISSN 0822 - 9473 Contents REPORT FROM THE CHAIR 1 NOTES FROM THE SECTION 5 Trail Rider Program 6 Wild Women 7 Exploring the back country in partnership with the ICA Youth and Family Services program 8 Happy Anniversary: Hišimy̓ awiƛ Celebrates Its First Year 10 Clarke Gourlay 1964 - 2019 16 VANCOUVER ISLAND 17 Finding Ice on Della Falls 17 Our Surprise Wedding at the Summit of Kings Peak 21 Mount Sebalhal and Kla-anch Peaks 24 Mt Colonel Foster – Great West Couloir 26 Climbing the Island’s Arch 36 Reflection Peaks At Last 39 Climbs in the Lower Tsitika Area: Catherine Peak, Mount Kokish, Tsitika Mountain and Tsitika Mountain Southeast 42 A Return to Triple Peak 45 Rockfall on Victoria Peak 48 Mt Mariner: A Journey From Sea to Sky 51 Beginner friendly all women Traverse of the Forbidden Plateau 54 It’s not only beautiful, its interesting! The geology of the 5040 Peak area 57 Myra Creek Watershed Traverse 59 Mt. -

DOCUMENT RESUME Elevations and Distances in the United

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 241 333 SE 044 120 TITLE Elevations and Distances in the United States. INSTITUTION Geological Survey (Dept. of Interior), Reston, Va. PUB DATE 80 NOTE 13p.; Photographs may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Geographic Materials (133) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Charts; *Distance; Earth Science; *Geographic Location; Geography; *Height; Instructional Materials; Physical Divisions (Geographic); *Physical Geography; *Proximity; Secondary Education; Tables (Data); Topography; Urban Areas IDENTIFIERS PF Project; Rocky Mountains; *United States ABSTRACT One of a series of general interest publications on science topics, the booklet proviees those interested in elevations and distances with a nontechnical introduction to the subject. The entire document consists of statistical charts depicting the nation's 50 largest cities, extreme and mean elevations, elevations of named summits over 14,000 feet above sea level, elevations of selected summits east of the Rocky Mountains, distances from extreme points to geographic centers, and lengths of United States boundaries. The elevations of features and distances between pbints in the United States were determined from surveys and topographic maps of the U.S. Geological Survey. (LH) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** . r Mee Notion's principal conservation agency, the Department AIthe *hider hoe responsibility for most of our nationally owned -MOM lends sad n,.twal ammo. This includes fostering the Elevations 'MN* Use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and ilitillie,:ermervinj the emoironmentsi and cultural values of our and Distances Malone parks sad.historlcM places, and providing for the enjoy- s _meat of life tha.: oh outdoor recrecion. -

Topography of the Southwestern US

Chapter 4: Topography of the topography • the landscape Southwestern US of an area, including the presence or absence of hills and the slopes between high and low areas. Does your region have rolling hills? Mountainous areas? Flat land where you never have to bike up a hill? The answers to these questions can help others understand the basic topography of your region. The term topography is used to describe the shape of the land surface as measured by how elevation— geologic time scale • a height above sea level—varies over large and small areas. Over geologic standard timeline used to time, topography changes as a result of weathering and erosion, as well as describe the age of rocks and fossils, and the events that the type and structure of the underlying bedrock. It is also a story of plate formed them. tectonics, volcanoes, folding, faulting, uplift, and mountain building. The Southwest’s topographic zones are under the influence of the destructive surface processes of weathering and erosion. Weathering includes both the plate tectonics • the process mechanical and chemical processes that break down a rock. There are two by which the plates of the types of weathering: physical and chemical. Physical weathering describes the Earth’s crust move and physical or mechanical breakdown of a rock, during which the rock is broken interact with one another at their boundaries. into smaller pieces but no chemical changes take place. Water, ice, and wind all contribute to physical weathering, sculpting the landscape into characteristic forms determined by the climate. In most areas, water is the primary agent of erosion. -

2013 – Salt Lake City, UT

SALT LAKE CITY 2013 AAPG-RMS SEPTEMBER 22-24 2013 AAPG Rocky Mountain Section Meeting Hosted by the Utah Geological Association The Program is sponsored by Newfield Exploration Company Thank you to our generous sponsors Mt. Elbert (CO) - 14,440 ft - >$5,000 Gannett Peak (WY) - 13,804 ft - $2,000 - $5,000 Kings Peak (UT) - 13,528 ft - $1,000 - $2,000 Wheeler Peak (NM) - 13,167 ft - $100 - $1,000 1 SALT LAKE CITY 2013 AAPG-RMS SEPTEMBER 22-24 WE WELCOME YOU TO SALT LAKE CITY On behalf of the Rocky Mountain Section of AAPG and the Utah Geological Association, we welcome you to Salt Lake City. The 2013 organizing committee has worked hard to prepare an excellent conference with diverse field trips, comprehen- sive short courses, and a technical program that highlights the latest research on a wide variety of geoscience topics. Don’t forget to check out the core posters, located in the exhibit hall, representing several major reservoir types in the Rockies. There are still tickets available for the private party at the new Natural History Museum of Utah on Monday evening. Located on the east bench, with panoramic views of the Salt Lake Valley, this 163,000-square-foot facility is one of the finest Natural History Museums in the country. The entire museum will be yours to explore and enjoy, along with dinner, drinks, and live music by the local folk band Otter Creek. The All-Convention Luncheon on Tuesday will step away from the traditional petroleum discussion and look to the heavens.