Time to Rein in Tunisia's Police Unions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Kirkpatrick, David D. "Moderate Islamist Party Heads Toward Victory in Tunisia."

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Kirkpatrick, David D. "Moderate Islamist Party Heads toward Victory in Tunisia." NY Times, New York Times, 24 Oct. 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/10/25/world/africa/ennahda-moderate-islamic-party-makes-stro ng-showing-in-tunisia-vote.html. Accessed 8 Jan. 2020. This article was especially helpful for information about the results of Tunisia's election. It mentioned how the modern Islamic group is very proud that they managed to win control of a country using fair elections. This article is trustworthy because it was published by the New York Times, which is a mainstream source that has minimal bias. "Report: 338 Killed during Tunisia Revolution." AP News, 12 May 2012, apnews.com/f91b86df98c34fb3abedc3d2e8accbcf. Accessed 14 Feb. 2020. I used this source to find more specific numbers for the deaths and injuries that happened due to the Tunisian Arab Spring. This article was issued by AP News which is considered to have accurate news and minimal bias. Ritfai, Ryan. "Timeline: Tunisia's Uprising." Al-jazeera, 23 Jan. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/spotlight/tunisia/2011/01/201114142223827361.html. Accessed 14 Feb. 2020. I used this source to affirm descriptive details such as the exact dates for important events. Al-Jazeera published this article and is considered accurate, liable, and unbiased. Ryan, Yasmine. "The Tragic Life of a Street Vendor." Al-jazeera, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2011/01/201111684242518839.html. Accessed 6 Ahmad 1 Feb. 2020. I used this source to find out if Ben Ali visited Bouazizi in the hospital. This article was published by Al-Jazeera which is a fact reporting and unbiased source. -

Political Transition in Tunisia

Political Transition in Tunisia Alexis Arieff Analyst in African Affairs April 15, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21666 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Political Transition in Tunisia Summary On January 14, 2011, President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled the country for Saudi Arabia following weeks of mounting anti-government protests. Tunisia’s mass popular uprising, dubbed the “Jasmine Revolution,” appears to have added momentum to anti-government and pro-reform sentiment in other countries across the region, and some policy makers view Tunisia as an important “test case” for democratic transitions elsewhere in the Middle East. Ben Ali’s departure was greeted by widespread euphoria within Tunisia. However, political instability, economic crisis, and insecurity are continuing challenges. On February 27, amid a resurgence in anti-government demonstrations, Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi (a holdover from Ben Ali’s administration) stepped down and was replaced by Béji Caïd Essebsi, an elder statesman from the administration of the late founding President Habib Bourguiba. On March 3, the interim government announced a new transition “road map” that would entail the election on July 24 of a “National Constituent Assembly.” The Assembly would, in turn, be charged with promulgating a new constitution ahead of expected presidential and parliamentary elections, which have not been scheduled. The protest movement has greeted the road map as a victory, but many questions remain concerning its implementation. Until January, Ben Ali and his Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD) party exerted near-total control over parliament, state and local governments, and most political activity. -

Complete TF Final Word

THE HENRY M. JACKSON SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ! CAN NATO REACT TO THE ARAB SPRING? DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, & THE RULE OF LAW February 27, 2012 The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington TASK FORCE 2012 Can NATO React to the Arab Spring?: Democracy, Human Rights, and the Rule of Law Task Force Advisor: Professor Christopher Jones Task Force Evaluator: Dr. Bates Gill, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Task Force Members: Andrea Banel Armando Cortes Alice Jacobson Jake Lustig Pavel Mantchev Morgan McAllister Kelsey Miller Margaret Moore (Editor) Francis Ramoin (Editor) Alyson Singh (Secretary) Hae Suh (Editor) Josiah Surface Samantha Thomas-Nadler Jasmine Zhang (Editor) ! TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tunisia [2-49] 1 INSTITUTIONS & DEMOCRACY BUILDING IN TUNISIA 2 1.1 Mohamed Ghannouchi and the Transition 1.2 The Justice System 6 1.3 The Election 7 1.4 Democracy Building in Tunisia and Iraq 10 1.5 NATO 12 2 THE MILITARY & FOREIGN INFLUENCE IN THE DOMESTIC AFFAIRS 16 OF TUNISIA 2.1 Background and Role of the Army in Society 17 2.2 Foreign Interests and Assistance to the Local Army 20 2.2.a United States 2.2.b Europe 22 2.3 Army in the Revolution and the Government Transition 25 2.4 Foreign Reactions to the Revolution 27 2.4.a Europe 2.4.b France 29 2.4.c United States 30 2.5 Post-Revolution Role of the Army 32 2.6 NATO 3 ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY? 36 3.1 The Theoretical Framework of Islamic Democracy 38 3.2 Shari’a Law 43 3.3 The History of Islamism -

The Initiators of the Arab Spring, Tunisia's Democratization Experience

The Initiators of the Arab Spring: Tunisia's Democratization Experience Uğur Pektaş Tunisia is seen as the birthplace of the Arab Spring, which is described as pro-democracy popular protests aimed at eliminating authoritarian governments in various Arab countries. The protests in Tunisia, which started with Mohamed Bouazizi's burning on December 17, 2010, ended without causing violence with the effect of Zine el Abidine Ben Ali’s departure from the country on January 14th. With its relatively low level of violence, Tunisia achieved the most successful outcome among the countries where the Arab Spring protests took place. In the decade after the authoritarian leader Ben Ali fled the country, significant progress has been made on the way to democracy in Tunisia. However, it can be said that the country's transition to democracy is still in limbo. Although 10 years have passed, Tunisians barely gained some political rights, but a backward economy and deterioration of the political fabric prevented these protests from reaching their goals. In the last 10 years, protesters took to the streets from time to time. If we take a general look at what happened in Tunisia in the last decade, it may be easier to understand the situation in question. An emergency was declared on January 14, 2011, following ongoing street protests. It has been announced that the government has dissolved and that general elections will be held within six months. Even this development did not end the protests and Ben Ali left the country. Fouad Mebazaa, the former spokesperson of the lower wing of the Tunisian Assembly, became the temporary president. -

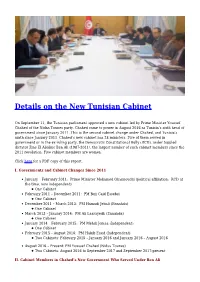

Details on the New Tunisian Cabinet

Details on the New Tunisian Cabinet On September 11, the Tunisian parliament approved a new cabinet led by Prime Minister Youssef Chahed of the Nidaa Tounes party. Chahed came to power in August 2016 as Tunisia’s sixth head of government since January 2011. This is the second cabinet change under Chahed, and Tunisia’s ninth since January 2011. Chahed’s new cabinet has 28 ministers. Five of them served in government or in the ex-ruling party, the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD), under toppled dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali (1987-2011), the largest number of such cabinet members since the 2011 revolution. Five cabinet members are women. Click here for a PDF copy of this report. I. Governments and Cabinet Changes Since 2011 January – February 2011: Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi (political affiliation: RCD at the time, now independent) One Cabinet February 2011 – December 2011: PM Beji Caid Essebsi One Cabinet December 2011 – March 2013: PM Hamadi Jebali (Ennahda) One Cabinet March 2013 – January 2014: PM Ali Laarayedh (Ennahda) One Cabinet January 2014 – February 2015: PM Mehdi Jomaa (Independent) One Cabinet February 2015 – August 2016: PM Habib Essid (Independent) Two Cabinets: February 2015 – January 2016 and January 2016 – August 2016 August 2016 – Present: PM Youssef Chahed (Nidaa Tounes) Two Cabinets: August 2016 to September 2017 and September 2017-present II. Cabinet Members in Chahed’s New Government Who Served Under Ben Ali Radhouane Ayara – Minister of Transportation Political affiliation: Nidaa Tounes New position, -

1 Tunisia: Igniting Arab Democracy

TUNISIA: IGNITING 1 ARAB DEMOCRACY By Dr. Laurence Michalak, 2013 ota Bene: At the time of publication, Tunis is experiencing large protests N calling for the resignation of the current moderate Islamist Ennahdha government. The demonstrations follow on the six-month anniversary of the still- unsolved assassination of Chokry Belaid, and in the wake of the killing in late July 2013 of a second secular leftist politician, Mohamed Brahmi. The national labour union, Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail (UGTT), has called on its hundreds of thousands of members to join the rally. Work on a new constitution and election law have been suspended. The constituent assembly has been suspended pending negotiations between the government and opposition, after 70 members withdrew in protest over Brahmi’s murder. The demonstrations are the largest of their kind since the ouster of Zine El Abine Ben Ali in January 2011. Elections are scheduled for December 2013. Tunisia is an instructive case study in democracy development because the uprising that began there in December 2010 has ignited an ongoing movement in the Arab world. Tunisia’s movement is still evolving, but a summary of events to date is as follows: • The Tunisian uprising was essentially homegrown, illustrating that democracy cannot be imported but must, in each country, emerge from the people themselves. • France, the most powerful diplomatic presence in Tunisia, gave almost unqualifed support to the autocratic President Ben Ali for nearly a quarter century, although the French Socialist government elected in May 2012 supports Tunisia’s democratic development. • The US supported President Ben Ali until the George W. -

Judicial Power in Transitional Regimes: Tunisia and Egypt Since the Arab Spring

JUDICIAL POWER IN TRANSITIONAL REGIMES: TUNISIA AND EGYPT SINCE THE ARAB SPRING A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Frederick Harris Setzer, January 2017 © 2017 Frederick Harris Setzer JUDICIAL POWER IN TRANSITIONAL REGIMES: TUNISIA AND EGYPT SINCE THE ARAB SPRING Frederick Harris Setzer, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2017 The dissertation examines the question of why political authorities assign different powers to courts during political transitions through the cases of Egypt and Tunisia following the 2011 uprisings. In Egypt, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces allowed the Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC) to continue exercising its power of constitutional review throughout the transition. In Tunisia, the transitional Ben Achour Commission dissolved the Constitutional Council and suspended constitutional review for the duration of the transition. The dissertation argues that the formal powers of courts after 2011 were determined by a two step process that hinges on ideas about the judicial role: first, relations between the courts and the old regime produced a set of ideas about the judicial role; second, these ideas constrained the political authorities that designed the transitional institutions following the 2011 revolutions. The dissertation considers two alternative explanations. First, the powers of courts may have been determined by the interests of political authorities for or against majority rule. Second, courts may have drawn support from civil society. If courts have allies in civil society, they are more able to claim additional formal powers. The dissertation rejects these explanations based on evidence from interviews with judges, lawyers and political parties, and a study of judicial decisions and transitional documents. -

Tunisia's Volatile Transition to Democracy

Tunisia’s Volatile Transition to Democracy November 6, 2015 POMEPS Briefings 27 Contents 2014 parliamentary and presidential elections Tunisian elections bring hope in uncertain times . 6 By Lindsay Benstead, Ellen Lust, Dhafer Malouche and Jakob Wichmann The richness of Tunisia’s new politics . .. 8 By Laryssa Chomiak Tunisia’s post-parliamentary election hangover . 10 By Danya Greenfield Three remarks on the Tunisian elections . 13 By Benjamin Preisler Tunisia opts for an inclusive new government . .. 15 By Monica Marks What happens when Islamists lose an election? . 19 By Rory McCarthy Economic, security and political challenges Tunisia’s golden age of crony capitalism . 22 By Bob Rijkers, Caroline Freund and Antonio Nucifora Why some Arabs don’t want democracy . 24 By Lindsay Benstead Tunisia’s economic status quo . 26 By Antonio Nucifora and Erik Churchill Tunisian voters balancing security and freedom . 27 By Chantal Berman, Elizabeth R. Nugent and Radhouane Addala Will Tunisia’s fragile transition survive the Sousse attack? . 30 By Rory McCarthy Comparative analysis and regional context What really made the Arab uprisings contagious? . 34 By Merouan Mekouar Why is Tunisian democracy succeeding while the Turkish model is failing? . 36 By Yüksel Sezgin Arab transitions and the old elite . 38 By Ellis Goldberg Why Tunisia didn’t follow Egypt’s path . 43 Sharan Grewal How Egypt’s coup really affected Tunisia’s Islamists . 46 By Monica Marks When it comes to democracy, Egyptians hate the player but Tunisians hate the game . 50 By Michael Robbins What the Arab protestors really wanted . 52 By Mark R. Beissinger, Amaney Jamal and Kevin Mazur Reflection on the National Dialogue Quartet’s Nobel Prize Could Tunisia’s National Dialogue model ever be replicated? . -

Model Arab League

Samuel Adelson, May 2013 Model Arab League Annotated Bibliography for Tunisia ncusar.org/modelarableague Model Arab League Research Resources: Tunisia Page 1 Samuel Adelson, May 2013 This annotated bibliography was created to serve as a research resource for students taking part in the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations’ Model Arab League Program. With the understanding that research can be intimidating and time consuming, an effort was made to find a set of scholarly articles that give a detailed background and thorough account of the current situation for this League of Arab States member. Included are annotations designed to give a description of the source with the intention of students completing the research on their own. There has been an attempt to focus on more contemporary scholarship, specifically post- 9/11 and post-2011 (so-called “Arab Spring”) where possible, as these are two phenomena that fundamentally changed politics in the Arab world. These sources should provide students with a solid basis for understanding the country they are representing in both regionally and globally significant issues as well as the interests of other countries within the League of Arab States. 1. Zouheir A. Maalej, “The 'Jasmine Revolt' has made the 'Arab Spring': A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Last Three Political Speeches of the Ousted President of Tunisia,” Discourse Society, Volume 23, Number 6, November 2012, pp. 679-700. •• Before Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali (former president of Tunisia) fled the country, he famously gave three speeches. Besides the fact that these speeches were conducted as an emergency response to the spreading Tunisian revolution, detailed analysis of the language Ben Ali used in each speech demonstrates critical changes in political posture and power. -

Tunisia Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Tunisia Country Report Status Index 1-10 5.74 # 60 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 5.80 # 64 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 5.68 # 62 of 129 Management Index 1-10 4.58 # 77 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Tunisia Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Tunisia 2 Key Indicators Population M 10.8 HDI 0.712 GDP p.c. $ 9794.6 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.0 HDI rank of 187 94 Gini Index 36.1 Life expectancy years 74.8 UN Education Index 0.646 Poverty3 % 4.3 Urban population % 66.5 Gender inequality2 0.261 Aid per capita $ 87.4 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary After President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali left the country on 14 January 2011, transitional governments under Mohamed Ghannouchi (17 January – 27 February 2011), Beji Caid Essebsi (27 February – 24 December 2011) and Hamadi Jebali (24 December 2011 – 19 February 2013) embarked on a transition process toward the establishment of a constitutionally based and democratically legitimized system of power relationships. -

The Civil Society in the Transition Souhayr BELHASSEN Interview

The civil society in the transition Souhayr BELHASSEN Interview with UNDP Civil society played a prominent and remarkable role in the institutional and democratic transition triggered by the departure of Zine el Abidine Ben Ali on 14 January 2011. The reason why stakeholders independent of the State and separate from any political group were able to be involved in this process from the start was that all the conditions for them to exist and act were in place, despite the constraints under previous regimes. The national movement had, from the beginning, been defined by the notion of Destour: the Constitution. Destour thought takes the Law as its basis and is rooted in the reformist movement, which significantly pre-dates independence and whose efforts to transform society relied on laws and the strengthening of State institutions. The fundamental choices of the first President of the independent Tunisian Republic, Habib Bourguiba, were decisive in shaping that transformation. His ascent to power marked the victory of the movement he embodied – a movement that was modern and open to the West, particularly France – over that of his opponent, Salah Ben Yousef, a nationalist, conservative current focused on the Arab and Muslim world. The change in women's status and the universal implementation of coeducation would, along with judicial reforms (in particular the dissolution of Sharia courts), be the levers Bourguiba used to make Tunisian society different from that of any other state in the Arab world. The Personal Status Code promulgated on 13 August 1956, before the 1959 Constitution had even been adopted, abolished polygamy and legalized divorce. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit „Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion“ Verfasserin Daniela Christiana Bichiou angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im Oktober 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 300 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Politikwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Otmar Höll Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion Seite 2 Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion Je vous remercie. Seite 3 Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion Seite 4 Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion Inhalt ABKÜRZUNGSVERZEICHNIS .............................................................................................................................. 7 VORWORT ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 1. EINLEITUNG ............................................................................................................................................ 10 2. THEORETISCHE GRUNDLAGE ..................................................................................................................