SUFAM Spring2010 19Th Century Costume Treasures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Cunning Isobel Meets Nanny”

© 2015 Angela M. Bauer All Rights Reserved Isobel Chapter 3 “Cunning Isobel Meets Nanny” Fiction by Angela Bauer Once Valery and Isobel were towel-dried after their Sunday night bath, their mommy Sylvia had them sit on their potties. Isobel produced nothing, but Valery managed to void a significant amount of pee and a moderate-size soft stool. They were wiped, diapered, given pacifiers and tucked into their cribs. During the night Sylvia checked and found Isobel’s diaper was nearly saturated, so she changed her older daughter. Then she decided to prophylactically change Valery’s diaper. Monday morning she let her girls sleep late in the nursery. Shortly before 8:00 A.M. she carried Valery and led Isobel downstairs while they were still wearing their night diapers and Onesies. She had just buckled the girls into their highchairs when the tallish and beautiful twenty-six year-old Nanny Carmen arrived. Sylvia had a bowl of the Pablum/Metamucil mixture in each hand. Hurriedly she put those on the respective highchair trays so she could properly greet Nanny Carmen. What impressed Carmen was that without fuss the smaller Valery picked up her own spoon and began eating her mixture. The far larger Isobel stared at her. After an exchange of greetings Sylvia hurried to bring Valery a Sippy cup of milk and a baby bottle of milk to Isobel. Only after holding that so Isobel could eagerly suckle a couple of ounces of milk did her mother begin to spoon-feed her the mixture. Page 1 © 2015 Angela M. -

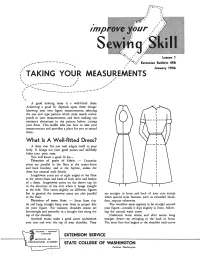

Taking Your Measurements \ I / \ I / ' ------/ / ' ,,,__

• 1mp s __ ...,... ___ _. _____ ___ ,,. -, Bulletin 498 / January 1956 / ' : TAKING YOUR MEASUREMENTS \ I / \ I / ' ------ / / ' ,,,__..... --- ------- ./ _,."' / / --- --- 1 -------------- \ \ ' A good looking dress is a well-fitted dress. Achieving a good fit depends upon three things: knowing your own figure measurements, selecting the size and type pattern which most nearly corres ponds to your measurements, and then making any necessary alterations in the pattern before cutting your dress. This leaflet tells you how to take your measurements and provides a place for you to record them. What Is A Well-fitted Dress? A dress that fits you well adapts itself to your body. Ir brings out your good points and skillfully hides your poor ones. You will know a good fit by- Direction of grain of fabric. - Crosswise yarns are parallel to the floor at the center-front and back busdine, and at the hipline, unless the dress has unusual style details. lengthwise yarns are at right angles to the floor at the center-front and back of both skirt and bodice of a dress. lengthwise yarns on the sleeve cap lie in the direction of the arm when it hangs straight at the side . This varies slightly on different figures but in general the crosswise yarns are also parallel are straight in front and back of your arm except to the floor. when special style features, such as extended shoul Direction of seam lines. - Seam lines that ders, requir.e otherwise. lie and hang straight keep your dress in proper li~e The waistline seam appears to be straight around on your figure. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

“The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space”: the Rise and Fall of The

Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ University of North Carolina Asheville “The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space”: The Rise and Fall of the Paper Dress in 1960s American Fashion A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History In Candidacy for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History By Virginia Knight Asheville, North Carolina November 2014 1 A woman stands in front of a mirror in a dressing room, a sales assistant by her side. The sales assistant, with arms full of clothing and a tape measure around her neck, beams at the woman, who is looking at her reflection with a confused stare. The woman is wearing what from the front appears to be a normal, knee-length floral dress. However, the mirror behind her reveals that the “dress” is actually a flimsy sheet of paper that is taped onto the woman and leaves her back-half exposed. The caption reads: “So these are the disposable paper dresses I’ve been reading about?” This newspaper cartoon pokes fun at one of the most defining fashion trends in American history: the paper dress of the late 1960s.1 In 1966, the American Scott Paper Company created a marketing campaign where customers sent in a coupon and shipping money to receive a dress made of a cellulose material called “Dura-Weave.” The coupon came with paper towels, and what began as a way to market Scott’s paper products became a unique trend of American fashion in the late 1960s. -

Cora Ginsburg Catalogue 2015

CORA GINSBURG LLC TITI HALLE OWNER A Catalogue of exquisite & rare works of art including 17th to 20th century costume textiles & needlework 2015 by appointment 19 East 74th Street tel 212-744-1352 New York, NY 10021 fax 212-879-1601 www.coraginsburg.com [email protected] NEEDLEWORK SWEET BAG OR SACHET English, third quarter of the 17th century For residents of seventeenth-century England, life was pungent. In order to combat the unpleasant odors emanating from open sewers, insufficiently bathed neighbors, and, from time to time, the bodies of plague victims, a variety of perfumed goods such as fans, handkerchiefs, gloves, and “sweet bags” were available for purchase. The tradition of offering embroidered sweet bags containing gifts of small scented objects, herbs, or money began in the mid-sixteenth century. Typically, they are about five inches square with a drawstring closure at the top and two to three covered drops at the bottom. Economical housewives could even create their own perfumed mixtures to put inside. A 1621 recipe “to make sweete bags with little cost” reads: Take the buttons of Roses dryed and watered with Rosewater three or foure times put them Muske powder of cloves Sinamon and a little mace mingle the roses and them together and putt them in little bags of Linnen with Powder. The present object has recently been identified as a rare surviving example of a large-format sweet bag, sometimes referred to as a “sachet.” Lined with blue silk taffeta, the verso of the central canvas section contains two flat slit pockets, opening on the long side, into which sprigs of herbs or sachets filled with perfumed powders could be slipped to scent a wardrobe or chest. -

Catalogue of the Famous Blackborne Museum Collection of Laces

'hladchorvS' The Famous Blackbome Collection The American Art Galleries Madison Square South New York j J ( o # I -legislation. BLACKB ORNE LA CE SALE. Metropolitan Museum Anxious to Acquire Rare Collection. ' The sale of laces by order of Vitail Benguiat at the American Art Galleries began j-esterday afternoon with low prices ranging from .$2 up. The sale will be continued to-day and to-morrow, when the famous Blackborne collection mil be sold, the entire 600 odd pieces In one lot. This collection, which was be- gun by the father of Arthur Blackborne In IS-W and ^ contmued by the son, shows the course of lace making for over 4(Xi ye^rs. It is valued at from .?40,fX)0 to $oO,0()0. It is a museum collection, and the Metropolitan Art Museum of this city would like to acciuire it, but hasnt the funds available. ' " With the addition of these laces the Metropolitan would probably have the finest collection of laces in the world," said the museum's lace authority, who has been studying the Blackborne laces since the collection opened, yesterday. " and there would be enough of much of it for the Washington and" Boston Mu- seums as well as our own. We have now a collection of lace that is probablv pqual to that of any in the world, "though other museums have better examples of some pieces than we have." Yesterday's sale brought SI. .350. ' ""• « mmov ON FREE VIEW AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK FROM SATURDAY, DECEMBER FIFTH UNTIL THE DATE OF SALE, INCLUSIVE THE FAMOUS ARTHUR BLACKBORNE COLLECTION TO BE SOLD ON THURSDAY, FRIDAY AND SATURDAY AFTERNOONS December 10th, 11th and 12th BEGINNING EACH AFTERNOON AT 2.30 o'CLOCK CATALOGUE OF THE FAMOUS BLACKBORNE Museum Collection of Laces BEAUTIFUL OLD TEXTILES HISTORICAL COSTUMES ANTIQUE JEWELRY AND FANS EXTRAORDINARY REGAL LACES RICH EMBROIDERIES ECCLESIASTICAL VESTMENTS AND OTHER INTERESTING OBJECTS OWNED BY AND TO BE SOLD BY ORDER OF MR. -

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes: I created this pattern as a companion for my women’s 1914 Afternoon Dress pattern. At right is an illustration from the 1914 Home Pattern Company catalogue. This is, essentially, what this pattern looks like if you make it up with an overskirt and cap sleeves. To get this exact look, you’d embroider the overskirt (or use eyelet), add a ruffle around the neckline and put cuffs on the straight sleeves. But the possibilities are as limitless as your imagination! Styles for little girls in 1914 had changed very little from the early Edwardian era—they just “relaxed” a bit. Sleeves and skirt styles varied somewhat over the years, but the basic silhouette remained the same. In the appendix of the print pattern, I give you several examples from clothing and pattern catalogues from 1902-1912 to show you how easy it is to take this basic pattern and modify it slightly for different years. Skirt length during the early 1900s was generally right at or just below the knee. If you make a deep hem on this pattern, that is where the skirt will hit. However, I prefer longer skirts and so made the pattern pieces long enough that the skirt will hit at mid-calf if you make a narrow hem. Of course, I always recommend that you measure the individual child for hem length. Not every child will fit exactly into one “standard” set of pattern measurements, as you’ll read below! Before you begin, please read all of the instructions. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

HISTORY and DEVELOPMENT of FASHION Phyllis G

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF FASHION Phyllis G. Tortora DOI: 10.2752/BEWDF/EDch10020a Abstract Although the nouns dress and fashion are often used interchangeably, scholars usually define them much more precisely. Based on the definition developed by researchers Joanne Eicher and Mary Ellen Roach Higgins, dress should encompass anything individuals do to modify, add to, enclose, or supplement the body. In some respects dress refers to material things or ways of treating material things, whereas fashion is a social phenomenon. This study, until the late twentieth century, has been undertaken in countries identified as “the West.” As early as the sixteenth century, publishers printed books depicting dress in different parts of the world. Books on historic European and folk dress appeared in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By the twentieth century the disciplines of psychology, sociology, anthropology, and some branches of art history began examining dress from their perspectives. The earliest writings about fashion consumption propose the “ trickle-down” theory, taken to explain why fashions change and how markets are created. Fashions, in this view, begin with an elite class adopting styles that are emulated by the less affluent. Western styles from the early Middle Ages seem to support this. Exceptions include Marie Antoinette’s romanticized shepherdess costumes. But any review of popular late-twentieth-century styles also find examples of the “bubbling up” process, such as inner-city African American youth styles. Today, despite the globalization of fashion, Western and non-Western fashion designers incorporate elements of the dress of other cultures into their work. An essential first step in undertaking to trace the history and development of fashion is the clarification and differentiation of terms. -

Diana's Favorite Things

Diana’s Favorite Things By Trail End State Historic Site Curator Dana Prater; from Trail End Notes, March 2000 “Girls in white dresses with blue satin sashes ... “ Although we didn’t find a blue satin sash, we recently discovered something even better. While cataloging items from the Manville Kendrick Estate collection, we had the pleasure of examining some fantastic dresses that belonged to Manville’s wife, Diana Cumming Kendrick. Fortunately for us, Diana saved many of her favorite things, and these dresses span almost sixty years of fashion history. Diana Cumming (far right) and friends, c1913 (Kendrick Collection, TESHS) Few things reveal as much about our personalities and lifestyles as our clothing, and Diana Kendrick’s clothes are no exception. There are two silk taffeta party dresses dating from around 1914-1916 and worn when Diana was a young teenager. The pink one is completely hand sewn and the rounded neckline and puffy sleeves are trimmed with beaded flowers on a net background. Pinked and ruched fabric ribbons loop completely around the very full skirt, which probably rustled delightfully when she danced. The pale green gown consists of an overdress with a shorter skirt and an underdress - almost like a slip. The skirt of the slip has the same pale green fabric and extends out from under the overskirt. Both skirt layers have a scalloped hem. A short bertha (like a stole) is attached at the back of the rounded neckline and wraps around the shoulders, repeating the scalloped motif and fastening at the front. This dress even includes a mini-bustle of stiff buckram to add fullness in the back. -

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 1 Apply style tape to your dress form to establish the bust level. Tape from the left apex to the side seam on the right side of the dress form. 1 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 2 Place style tape along the front princess line from shoulder line to waistline. 2 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3A On the back, measure the neck to the waist and divide that by 4. The top fourth is the shoulder blade level. 3 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3B Style tape the shoulder blade level from center back to the armhole ridge. Be sure that your guidelines lines are parallel to the floor. 4 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 4 Place style tape along the back princess line from shoulder to waist. 5 Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 1 To find the width of your center front block, measure the widest part of the cross chest, from princess line to centerfront and add 4”. Record that measurement. 6 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 2 For your side front block, measure the widest part from apex to side seam and add 4”. 7 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 3 For the length of both blocks, measure from the neckband to the middle of the waist tape and add 4”. 8 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 4 On the back, measure at the widest part of the center back to princess style line and add 4”. -

Ajsl ,QJI 8Ji)9

ajsL ,QJI 8jI)9 MINSTRY OF SOCIAL AFFAIRS L",uitom cz4 /ppaLf ('"oduaDon P'"zuocz1 Volume 2 TAILORING //, INTEGRATED SOCIAL SERVICES PROJECT aLSioJ 8jsto!*14I 3toj3JI J54o 4sjflko MINSTRY OF SOCIAL AFFAIRS cwitom c92/I/2a'LEf ?'oduation 57P/D 0 E15 ('uvzicul'um JoL CSPP nstzucto~ Volume 2 TAILORING g~jji~JI 6&= z#jJEi l tl / INTEGRATED SOCIAL SERVICES PROJECT wotsoi stoim 1oj3jw jsi.Lo 6suJf PREFACE The material which follows is .J l.a ,,h &*.aJIL& . part of a five volume series assem bled by the faculty and students of . 3aJ e~- t.l. -, r'- ,tY.. the University of North Carolina at L_:J q L--, X4 0-j VO Greensboro, Department of Clothing and Textiles, CAPP Summer Program. The CAPP, Custom Appar,1 Production LFJI L,4.," ,'"i u .U. J l Process, Program was initiated in Egypt as a part of the Integrated Social Services Project, Dr. Salah L-,S l k e. L C-j,,. El Din El Hommossani, Project Direc- - L0 C...J L'j tor, and under the sponsorship of 4 " r th Egyptian Ministry of Social !.Zl ij1.,1,,.B= r,L..,J1....J Affairs and the U.S. Agency for - .Jt , . -t. International Development. These materials were designed for use in . J L.Jt CSziJtAJI #&h* - L*J training CAPP related instructors t .L-- -- J and supervisors for the various programs of the Ministry of Social ._ . , .. .. Affairs and to provide such person- L , *i. l I-JL-j 6 h nel with a systematica,'ly organized und detailed curriculum plan which JL61tJ J..i..- J" could be verbally transferred to O| ->.