HISTORY and DEVELOPMENT of FASHION Phyllis G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitably Chic Lynn Willis

Philadelphia University Spring 2007 development of (PRODUCT) RED, a campaign significantly embraced by the fashion community. Companies working with Focus on . Alumni Focus on . Industry News (PRODUCT) RED donate a large percentage of their profits to the Global Fund to fight Lynn Willis Charitably Chic AIDS. For example, Emporio Armani’s line donates 40 percent of the gross profit By Sara Wetterlin and Chaisley Lussier By Kelsey Rose, Erin Satchell and Holly Ronan margin from its sales and the GAP donates Lynn Willis 50 percent. Additionally, American Express, Trends in fashion come and go, but graduated perhaps the first large company to join the fashions that promote important social from campaign, offers customers its RED card, causes are today’s “it” items. By working where one percent of a user’s purchases Philadelphia with charitable organizations, designers, University in goes toward funding AIDS research and companies and celebrities alike are jumping treatment. Motorola and Apple have also 1994 with on the bandwagon to help promote AIDS a Bachelor created red versions of their electronics and cancer awareness. that benefit the cause. The results from of Science In previous years, Ralph Lauren has the (PRODUCT) RED campaign have been in Fashion offered his time and millions of dollars to significant, with contributions totaling over Design. Willis breast cancer research and treatment, which $1.25 million in May 2006. is senior includes the establishment of health centers Despite the fashion industry’s focus on director for the disease. Now, Lauren has taken image, think about what you can do for of public his philanthropy further by lending his someone else when purchasing clothes relations Polo logo to the breast cancer cause with and other items. -

Techniques of Fashion Earrings Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TECHNIQUES OF FASHION EARRINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Deon Delange | 72 pages | 01 Sep 1995 | Eagles View Publishing | 9780943604442 | English | Liberty, Utah, United States Techniques of Fashion Earrings PDF Book These stunning geometric earrings are perfect for a night out on the town or a shopping trip with the girls. And even if you don't go straight over your pencil lines, just kind of go with the flow; let your body feel it as you go. Trends influence what all of us wear to some extent, which is fine. Brendan How to draw human body for fashion design? Do share with us your creations! Two completely different looks, one set of clothe. Spice up some simple silver hoops with this awesome video tutorial for how to make bead earrings. You'll end up losing yourself. My advice? Make a note of the combinations you like if that helps to trigger your memory later. Stringing beads on multiple wires. The days of only wearing one tone of metal is over. When it comes to DIY jewelry, beaded earrings are some of the prettiest patterns out there. As an illustration, one pair of earring contains three hanging flowers: gentle pink, pale purple, and deep purple. Your email address will not be published. Tutorial Features: This beaded Christmas tree pattern will teach you how to make peyote stitch earrings and a peyote stitch necklace. All these bangle styles may be worn in one or each arms relying in your outfit, model and occasion. Eco-friendly jewellery. Try some dangling pearl earrings with a summer print for a fun and flirty look. -

JEWELLERY TREND REPORT 3 2 NDCJEWELLERY TREND REPORT 2021 Natural Diamonds Are Everlasting

TREND REPORT ew l y 2021 STATEMENT J CUFFS SHOULDER DUSTERS GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY GEOMETRIC DESIGNS PRESENTED BY THE NEW HEIRLOOM CONTENTS 2 THE STYLE COLLECTIVE 4 INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 8 STATEMENT CUFFS IN AN UNPREDICTABLE YEAR, we all learnt to 12 LARGER THAN LIFE fi nd our peace. We seek happiness in the little By Anaita Shroff Adajania things, embark upon meaningful journeys, and hold hope for a sense of stability. This 16 SHOULDER DUSTERS is also why we gravitate towards natural diamonds–strong and enduring, they give us 20 THE STONE AGE reason to celebrate, and allow us to express our love and affection. Mostly, though, they By Sarah Royce-Greensill offer inspiration. 22 GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY Our fi rst-ever Trend Report showcases natural diamonds like you have never seen 26 HIS & HERS before. Yet, they continue to retain their inherent value and appeal, one that ensures By Bibhu Mohapatra they stay relevant for future generations. We put together a Style Collective and had 28 GEOMETRIC DESIGNS numerous conversations—with nuance and perspective, these freewheeling discussions with eight tastemakers made way for the defi nitive jewellery 32 SHAPESHIFTER trends for 2021. That they range from statement cuffs to geometric designs By Katerina Perez only illustrates the versatility of their central stone, the diamond. Natural diamonds have always been at the forefront of fashion, symbolic of 36 THE NEW HEIRLOOM timelessness and emotion. Whether worn as an accessory or an ally, diamonds not only impress but express how we feel and who we are. This report is a 41 THE PRIDE OF BARODA product of love and labour, and I hope it inspires you to wear your personality, By HH Maharani Radhikaraje and most importantly, have fun with jewellery. -

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 1 Apply style tape to your dress form to establish the bust level. Tape from the left apex to the side seam on the right side of the dress form. 1 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 2 Place style tape along the front princess line from shoulder line to waistline. 2 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3A On the back, measure the neck to the waist and divide that by 4. The top fourth is the shoulder blade level. 3 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3B Style tape the shoulder blade level from center back to the armhole ridge. Be sure that your guidelines lines are parallel to the floor. 4 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 4 Place style tape along the back princess line from shoulder to waist. 5 Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 1 To find the width of your center front block, measure the widest part of the cross chest, from princess line to centerfront and add 4”. Record that measurement. 6 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 2 For your side front block, measure the widest part from apex to side seam and add 4”. 7 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 3 For the length of both blocks, measure from the neckband to the middle of the waist tape and add 4”. 8 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 4 On the back, measure at the widest part of the center back to princess style line and add 4”. -

Modern Pattern Design by Harriet Pepin

1942—Modern Pattern Design by Harriet Pepin Chapter 1—Pattern Designing Description of Equipment As the doctor, sculptor or artist should understand the purpose of various tools and equipment common to his profession, it is equally important that the patternmaker understands the purpose for which his equipment has been designed. Most of the following articles may be purchased at art supply houses, tailor's supply firms or at the notion departments in retail stores: 1. Triangle: The transparent right triangle is useful in pattern making to "square" a corner. The two smaller points will serve to establish a true bias from a vertical or horizontal line. Diagrams in problems which follow illustrate how this is done. In the study of geometry we learn that a triangle must total 180 degrees. This right triangle has two 45 degree angles and one 90 degree angle. 2. Tracing Wheel: This clever instrument saves hours of needless labor of thread marking. It is used to transfer lines or symbols from one pattern to another or from the final pattern to the muslin or fabric. When the test muslins are being made by the designer, ordinary pencil carbon may be used. When actual garments are being cut, white carbon or chalk boards are used. These markings can be easily removed later. 3. Carbon Boards: A suitable carbon board can be made by purchasing a 24 × 36 sheet of pencil carbon from an art supply house. This should be laid, face upward, upon a similar size piece of heavy cardboard or ply board. Then a length of cheese cloth is laid over and securely fastened to the back of the board with gum tape or thumb tacks. -

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles – c. 1790-1900 1790-1809 – Neoclassicism In the late 18th century, the latest fashions were influenced by the Rococo and Neo-classical tastes of the French royal courts. Elaborate striped silk gowns gave way to plain white ones made from printed cotton, calico or muslin. The dresses were typically high-waisted (empire line) narrow tubular shifts, unboned and unfitted, but their minimalist style and tight silhouette would have made them extremely unforgiving! Underneath these dresses, the wearer would have worn a cotton shift, under-slip and half-stays (similar to a corset) stiffened with strips of whalebone to support the bust, but it would have been impossible for them to have worn the multiple layers of foundation garments that they had done previously. (Left) Fashion plate showing the neoclassical style of dresses popular in the late 18th century (Right) a similar style ball- gown in the museum’s collections, reputedly worn at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball (1815) There was public outcry about these “naked fashions,” but by modern standards, the quantity of underclothes worn was far from alarming. What was so shocking to the Regency sense of prudery was the novelty of a dress made of such transparent material as to allow a “liberal revelation of the human shape” compared to what had gone before, when the aim had been to conceal the figure. Women adopted split-leg drawers, which had previously been the preserve of men, and subsequently pantalettes (pantaloons), where the lower section of the leg was intended to be seen, which was deemed even more shocking! On a practical note, wearing a short sleeved thin muslin shift dress in the cold British climate would have been far from ideal, which gave way to a growing trend for wearing stoles, capes and pelisses to provide additional warmth. -

Get a Taste of Theatre Design with Our Newest Series: the Old Globe Coloring Book! Every Thursday, We'll Post a New Page Featu

Get a taste of theatre design with our newest series: The Old Globe Coloring Book! Every Thursday, we’ll post a new page featuring an original design for costumes, sets, or props from past Globe shows. Along the way, you’ll be treated to design insight from artisans who brought these ideas to life. Color them in however you want (creativity welcome!), and post on your social media and tag @theoldglobe and #globecoloringbook. The following Tuesday, we’ll post some of our favorites, along with the designer’s original rendering and a photo of the final design onstage. It’s time for your vision to take the spotlight! Hamlet: Laertes, a young lord Dashing in a velvet cloak and cap, a richly textured houndstooth doublet (jacket) and breeches (calf length trousers). Cap is decorated with ostrich plumes, often placed on the left side of the cap leaving the right sword arm free to fight. A sword was an essential part of a gentlemen’s dress in the 17th century. Hamlet: In this 2007 production of Hamlet, the costumes were made from silk and wool fabrics in the shades of pale grey. In contrast, the main character, Hamlet, wore both a black and a scarlet suede doublet and breeches. The ladies were dressed in long sumptous gowns with corsets and padded petticoats. Sword fighting and scheming was afoot under the stars on the magical outdoor Lowell Davies Festival Stage. Familiar: Anne, eccentric aunt from Zimbabwe Costumed in grand style in a long colorful floral cotton skirt, blouse with large sleeve ruffles, and matching headdress. -

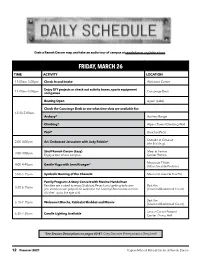

Sample Schedule

Grab a Ramah Darom map and take an audio tour of campus at ramahdarom�org/take-a-tour FRIDAY, MARCH 26 TIME ACTIVITY LOCATION 11:00am-5:00pm Check In and Intake Welcome Center Enjoy DIY projects or check out activity boxes, sports equipment 11:00am-5:00pm Concierge Desk and games Boating Open Agam (Lake) Check the Concierge Desk to see what time slots are available for: 12:30-5:00pm Archery* Archery Range Climbing* Alpine Tower/Climbing Wall Pool* Breicha (Pool) Outside of Omanut 2:00-4:00pm Art: Embossed Jerusalem with Judy Robkin* (Art Building) Stroll Ramah Darom (Easy) Meet at Levine 3:00-4:00pm Enjoy a tour of our campus. Center Portico Mirpesset T'fillah 4:00-4:45pm Gentle Yoga with Jenn Krueger* (Mountainside Pavilion) 5:00-5:15pm Symbolic Burning of the Chametz Medura (Lakeside Fire Pit) Family Program: A Story Concert with Maxine Handelman Families are invited to enjoy Shabbat, Pesach and getting-to-know- Beit Am 5:30-6:15pm you stories as we prepare to welcome the holiday! Recommended for (Covered Basketball Court) children up to the age of 8. Beit Am 6:15-7:15pm Welcome! Mincha, Kabbalat Shabbat and Maariv (Covered Basketball Court) Levine Center Portico/ 6:30-7:30pm Candle Lighting Available Center Dining Hall *See Session Descriptions on pages 40-41. Grey Denotes Preregistration Required! 12 Passover 2021 Kaplan Mitchell Retreat Center at Ramah Darom FRIDAY, MARCH 26 TIME ACTIVITY LOCATION 7:30-9:00pm Shabbat Dinner Chadar Ochel (Dining Hall) The Rabbi, The Witch and The Prevaricator: The Life of Shimon ben Shetach with Maharat Rori Picker Neiss Shimon ben Shetach is well-known for hunting witches. -

Reta Blossom in Corset and Bustle

MARCH 10. 1935. CHICAGO SUNDAY TRIBUNE: n 9 PART 7-PAGE 12. S££SZ$i "'9 . • • reta Blossom Out In Corset and Bustle In Next ilm HOll YWOOD Period Stvles Hollywood Men I Abhor Sartorial HAPPENINGS Revived for RUSSIAN APPEARING Perfection Now Bob Hopkins, comedy writer at DANCER AT M.·G.-M. has bought him a ranch at Russian Tale IN EARLY any actress In Holly· Encino, near Eddie Horton's. He wood would be set pleasurably THE PALACE says he wants some " first run fresh 'GIGOlETTE' a-twitter if she were to be air," I' A n n a Karenma." De- N asked how she achieves that Bob Taylor, leading man in well dressed effect. Yet try asking "Times Square Lady," Is entering mands rwenty-Five Fus- Clark Gable, Bill Powell, Warner Baxter, Robert Montgomery-and his third name, as above. He had sy,Complex Ensembles. they are liable to answer succinctly, two others which proved unlucky . ••Nerts." Any actress will spend the But the third one he's keeping as it whole day in front of a camera tak- seems to be taking him places. By Rosalind Shaffer. ing fashion stills-but try to get a Francis Lederer remarked the OLLYWOOD, Cal. - [Special.] single male star to model any gar- - Greta Garbo will burst ment and he's sure to have a date to other day that, in his opinion, Bette upon her faithful but ott- go duck hunting or something. Davis In her performance in ••Of times startled public in cor- There simply aren't any " best Suzanne Choumetska Human Bondage" merited the acad- set, bustle, and other feminine acces- dressed men" in Hollywood except is prominent in the emy award for which she was not sories to charm in her next film. -

ADDENDUM (Helps for the Teacher) 8/2015

ADDENDUM (Helps for the teacher) 8/2015 Fashion Design Studio (Formerly Fashion Strategies) Levels: Grades 9-12 Units of Credit: 0.50 CIP Code: 20.0306 Core Code: 34-01-00-00-140 Prerequisite: None Skill Test: # 355 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course explores how fashion influences everyday life and introduces students to the fashion industry. Topics covered include: fashion fundamentals, elements and principles of design, textiles, consumerism, and fashion related careers, with an emphasis on personal application. This course will strengthen comprehension of concepts and standards outlined in Sciences, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) education. FCCLA and/or DECA may be an integral part of this course. (Standards 1-5 will be covered on Skill Certification Test #355) CORE STANDARDS, OBJECTIVES, AND INDICATORS Performance Objective 1: Complete FCCLA Step One and/or introduce DECA http://www.uen.org/cte/facs_cabinet/facs_cabinet10.shtml www.deca.org STANDARD 1 Students will explore the fundamentals of fashion. Objective 1: Identify why we wear clothes. a. Protection – clothing that provides physical safeguards to the body, preventing harm from climate and environment. b. Adornment – using individual wardrobe to add decoration or ornamentation. c. Identification – clothing that establishes who someone is, what they do, or to which group(s) they belong. d. Modesty - covering the body according to the code of decency established by society. e. Status – establishing one’s position or rank in comparison to others. Objective 2: Define terminology. a. Common terms: a. Accessories – articles added to complete or enhance an outfit. Shoes, belts, handbags, jewelry, etc. b. Apparel – all men's, women's, and children's clothing c. -

VTE Framework: Fashion Technology

Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education Vocational Technical Education Framework Business & Consumer Services Occupational Cluster Fashion Technology (VFASH) CIP Code 500407 June 2014 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, MA 02148-4906 781-338-3910 www.doe.mass.edu/cte/ This document was prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Mitchell D. Chester, Ed.D. Commissioner Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Members Ms. Maura Banta, Chair, Melrose Ms. Harneen Chernow, Vice Chair, Jamaica Plain Mr. Daniel Brogan, Chair, Student Advisory Council, Dennis Dr. Vanessa Calderón-Rosado, Milton Ms. Karen Daniels, Milton Ms. Ruth Kaplan, Brookline Dr. Matthew Malone, Secretary of Education, Roslindale Mr. James O’S., Morton, Springfield Dr. Pendred E. Noyce, Weston Mr. David Roach, Sutton Mitchell D. Chester, Ed.D., Commissioner and Secretary to the Board The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, an affirmative action employer, is committed to ensuring that all of its programs and facilities are accessible to all members of the public. We do not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, national origin, race, religion, sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Inquiries regarding the Department’s compliance with Title IX and other civil rights laws may be directed to the Human Resources Director, 75 Pleasant St., Malden, MA 02148-4906. Phone: 781-338-6105. © 2014 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Permission is hereby granted to copy any or all parts of this document for non-commercial educational purposes. -

5 Clothing Technology Eng Oc

Content Page 5.1 Garment Ease and Fitting 1 5.1.1 Garment Ease 1 5.1.2 Garment Fitting 3 5.2 Pattern construction 7 5.2.1 Measurement and Sizing 7 5.2.2 Methods of Pattern Construction 13 5.2.3 Individual and Commercial Pattern Construction 21 Process 5.3 Garment Construction 23 5.3.1 Construction of Garment Parts 23 5.3.2 Trimmings and Fastenings 58 5.4 Industrial Technologies 69 5.4.1 Industrial Sewing Machine 69 5.4.2 Laser Technology 72 5.4.3 Automatic Data Collection System 75 5.1 Garment Ease and Fitting 5.1.1 Garment Ease Garments require adequate ease to provide and allow room for movement. Ease is the extra allowance added on the body measurement in pattern construction. Ease is different between garment measurement and body measurement. The exact dimensions of the body are without any addition room for comfort or movement. There are two types of ease: Wearing Ease and Design Ease. The measurement of a garment should consider the measurement of the wearer’s body, wearing ease and design ease. Body Wearing Design Fashion Style + + = Measurement Ease Ease or Silhouette Figure 5.1 The sizing design of a fashion garment Wearing ease Design ease Figure 5.2 Wearing ease – to show the basic ease on the dress for allowing the body to move comfortable. Design ease – extra ease to add into the dress by the designer to change the silhouette. 1 (A) Wearing Ease Wearing ease (comfort ease or fitting ease) must be required in all garments for body movement.