Historic Medical Perspectives of Corseting and Two Physiologic Studies with Reenactors Colleen Ruby Gau Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

CBU Student Handbook

DELIVERY OF INSTRUCTION California Baptist University expects to deliver instruction to its students through its traditional in-person and online formats. By attending the University, students acknowledge this expectation and understand that the University may be compelled to modify course instruction formats due to circumstances or events beyond the University’s reasonable control such as acts of God, acts of government, war, disease, social unrest, and accidents. As such, students attending the University assume the risk that circumstances may arise that mandate the closure of the campus or place restrictions upon the University’s delivery of instruction. By attending the University, each student understands and agrees that they will not be entitled to a refund or price adjustment for the cost of course instruction if their courses are required to be provided in a modified format which the University deems appropriate under such circumstances. 2021-2022 Student Handbook i California Baptist University | 09.24.21 TABLE OF CONTENTS Delivery of Instruction .................................................................................................................................................................................... i Personnel Directory ....................................................................................................................................................................................... ix Administration .................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

![Water-Cures [Moss-2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2187/water-cures-moss-2-122187.webp)

Water-Cures [Moss-2]

Fountains ofYouth NEW JERSEY’S WATER-CURES his is a story about the bustling medical by Sandra W. marketplace in nineteenth-century New Moss M.D., M.A. T Jersey, and, in particular, the establishments known as water-cures. What we now call alternative, complementary, or holistic medicine was once referred to as sectarian medicine and its Sandra Moss. M.D., M.A. (History) practitioners as irregulars. Most regular or orthodox is a retired internist and past president of the Medical History Society of New Jersey. Dr. Moss writes and speaks physicians, often called "allopaths" by their critics, about the history of medicine in New Jersey. viewed the endless parade of irregular sectarian Acknowledgements: This paper is dedicated to the memory practitioners as either ignorant quacks or educated, of Professor David L. Cowen (1909-22006), New Jersey’s premier medical historian. Archivist Lois Densky-WWolff, but deluded, quacks. In order to get our bearings, Special Collections, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, provided expert research assistance, as did we must look briefly at botanical and homeopathic the staff at Rutgers University Archives and Special sects before turning to the hydropaths, hygeio- Collections. therapists, and naturopaths. Fountains of Youth O Sandra W. Moss, MD, MA O GardenStateLegacy.com Issue 2 O December 2008 FROM JERSEY TEA struggling to make a living. Repeatedly TO JERSEY CURE stymied in its efforts to control Botanical medicine was a mainstay in practice through state licensing, the New Jersey from colonial times. “Herb regular medical establishment dithered “Water” and root” doctors and genuine (or for decades over the problem of by A.S.A. -

Phrenology Head

What’s on your mind? This is a classic picture stimulus that never fails to engage interest and generate dialogue. It works with young people from Key Stage Three right through to adults. Both the idea of phrenology and the image of a phrenology head are rich in possibilities, but this picture is extra rich because it shows the cover of a popular nineteenth century phrenological journal, and this has slogans like ‘Home Truths for Home Consumption’ and ‘Know Thyself’. Here’s one way to use this stimulus. 1. Provoke some discovery thinking It can go up on the screen, but its good to print off copies so small groups can gather around the image for a couple of minutes to try to make sense of it. It is beneficial to let them struggle and then have them feed back to the whole class with their first impressions. It is also useful to prompt some of this discovery thinking with questions like ‘What are we looking at?’, ‘Any clues about who this is aimed at?’, ‘What might the compartments be?’, ‘What is a journal?’ 2. Convey some information about phrenology 2.1. Phrenology was a very popular nineteenth century practice. 2.2. It was based on the idea that the mind has distinct functions that are located in different parts of the brain. 2.3. People believed that the more developed a particular function is, the bigger that part of the brain is. 2.4. They also believed that the shape of the person’s skull was determined by the relative development of each part of their brain . -

Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino: Full Transcript of the Interview

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH FASHION Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino C1046/09 IMPORTANT Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 [0]20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. THE NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION INTERVIEW SUMMARY SHEET Ref. No.: C1046/09 Playback No.: F15198-99; F15388-90; F15531-35; F15591-92 Collection title: An Oral History of British Fashion Interviewee’s surname: Savage Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: Percy Sex: Occupation: Date of birth: 12.10.1926 Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Date(s) of recording: 04.06.2004; 11.06.2004; 02.07.2004; 09.07.2004; 16.07.2004 Location of interview: Name of interviewer: Linda Sandino Type of recorder: Marantz Total no. of tapes: 12 Type of tape: C60 Mono or stereo: stereo Speed: Noise reduction: Original or copy: original Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Interview is open. Copyright of BL Interviewer’s comments: Percy Savage Page 1 C1046/09 Tape 1 Side A (part 1) Tape 1 Side A [part 1] .....to plug it in? No we don’t. Not unless something goes wrong. [inaudible] see well enough, because I can put the [inaudible] light on, if you like? Yes, no, lovely, lovely, thank you. -

A Peak Inside a Pumpkin Yellow Corset

Corset ca. 1900s. Ryerson FRC2013.05.001. Donated by Ingrid Mida. Photograph by Millie Yates, 2015. A PEEK INSIDE A PUMPKIN YELLOW CORSET By FRC Team This under bust corset (FRC 2013.05.001), dated 1900, is made of a rich pumpkin coloured woven jacquard cotton with a motif of staggered flower May 2, 2016 buds and stems (Note 1). The corset is lavishly trimmed with lace threaded with a similar yellow toned satin ribbon along the busk, and top and bottom edges. The centre front closes with metal slot and studs that are unmarked. The spoon busk measures 12 ¾ inches, with hand-stitching visible at the openings for surrounding each of the slots of the busk. The closed waist measures 23 inches, and there is notable discolouration along the panels along the waistline of the corset, as well as signs of wear including small stains and discolouration. Looking closely, there appears to have been four separate remnants of stitching resembling the shape of a dart, located respectively on each side of the front and back of the corset. There are 12 pairs of metal eyelets on the back to lace the corset; however the original laces are not present. The corset is lightly boned with 5 flexible bones placed directly beside each other, on each side of the corset, as well as one bone on either side of the eyelets at the back. One of the bones located on the back pokes out of the casing at revealing what appears to be ¼ inch flat white metal bone. The garment appears to have been sewn by machine; however the stitching is noticeably lacking fluidity and accuracy. -

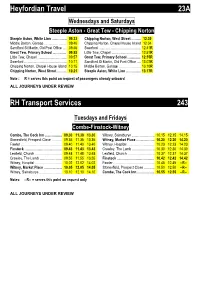

Timetables for Bus Services Under Review

Heyfordian Travel 23A Wednesdays and Saturdays Steeple Aston - Great Tew - Chipping Norton Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 09.33 Chipping Norton, West Street ……… 12.30 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 09.40 Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 12.34 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 09.46 Swerford ………………………………… 12.41R Great Tew, Primary School ………… 09.53 Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 12.51R Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 09.57 Great Tew, Primary School ………… 12.55R Swerford ………………………………… 10.11 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 13.02R Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 10.15 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 13.10R Chipping Norton, West Street ……... 10.21 Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 13.17R Note : R = serves this point on request of passengers already onboard ALL JOURNEYS UNDER REVIEW RH Transport Services 243 Tuesdays and Fridays Combe-Finstock-Witney Combe, The Cock Inn ………........ 09.30 11.30 13.30 Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.15 12.15 14.15 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 09.35 11.35 13.35 Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.20 12.20 14.20 Fawler ……………………………….. 09.40 11.40 13.40 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.23 12.23 14.23 Finstock ……………………………. 09.43 11.43 13.43 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 10.30 12.30 14.30 Leafield, Church ………………........ 09.48 11.48 13.48 Leafield, Church ………………........ 10.37 12.37 14.37 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 09.55 11.55 13.55 Finstock ……………………………. 10.42 12.42 14.42 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.02 12.02 14.02 Fawler ……………………………….. 10.45 12.45 --R-- Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.05 12.05 14.05 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 10.50 12.50 --R-- Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.10 12.10 14.10 Combe, The Cock Inn ………....... -

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes: I created this pattern as a companion for my women’s 1914 Afternoon Dress pattern. At right is an illustration from the 1914 Home Pattern Company catalogue. This is, essentially, what this pattern looks like if you make it up with an overskirt and cap sleeves. To get this exact look, you’d embroider the overskirt (or use eyelet), add a ruffle around the neckline and put cuffs on the straight sleeves. But the possibilities are as limitless as your imagination! Styles for little girls in 1914 had changed very little from the early Edwardian era—they just “relaxed” a bit. Sleeves and skirt styles varied somewhat over the years, but the basic silhouette remained the same. In the appendix of the print pattern, I give you several examples from clothing and pattern catalogues from 1902-1912 to show you how easy it is to take this basic pattern and modify it slightly for different years. Skirt length during the early 1900s was generally right at or just below the knee. If you make a deep hem on this pattern, that is where the skirt will hit. However, I prefer longer skirts and so made the pattern pieces long enough that the skirt will hit at mid-calf if you make a narrow hem. Of course, I always recommend that you measure the individual child for hem length. Not every child will fit exactly into one “standard” set of pattern measurements, as you’ll read below! Before you begin, please read all of the instructions. -

HISTORY and DEVELOPMENT of FASHION Phyllis G

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF FASHION Phyllis G. Tortora DOI: 10.2752/BEWDF/EDch10020a Abstract Although the nouns dress and fashion are often used interchangeably, scholars usually define them much more precisely. Based on the definition developed by researchers Joanne Eicher and Mary Ellen Roach Higgins, dress should encompass anything individuals do to modify, add to, enclose, or supplement the body. In some respects dress refers to material things or ways of treating material things, whereas fashion is a social phenomenon. This study, until the late twentieth century, has been undertaken in countries identified as “the West.” As early as the sixteenth century, publishers printed books depicting dress in different parts of the world. Books on historic European and folk dress appeared in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By the twentieth century the disciplines of psychology, sociology, anthropology, and some branches of art history began examining dress from their perspectives. The earliest writings about fashion consumption propose the “ trickle-down” theory, taken to explain why fashions change and how markets are created. Fashions, in this view, begin with an elite class adopting styles that are emulated by the less affluent. Western styles from the early Middle Ages seem to support this. Exceptions include Marie Antoinette’s romanticized shepherdess costumes. But any review of popular late-twentieth-century styles also find examples of the “bubbling up” process, such as inner-city African American youth styles. Today, despite the globalization of fashion, Western and non-Western fashion designers incorporate elements of the dress of other cultures into their work. An essential first step in undertaking to trace the history and development of fashion is the clarification and differentiation of terms. -

The Corset and the Crinoline : a Book of Modes and Costumes from Remote Periods to the Present Time

THE CORSET THE CRINOLINE. # A BOOK oh MODES AND COSTUMES FROM REMOTE PERIODS TO THE PRESENT TIME. By W. B. L. WITH 54 FULL-PAGE AND OTHER ENGRAVINGS. " wha will shoe my fair foot, Aud wha will glove my han' ? And wha will lace my middle jimp Wi' a new-made London ban' ?" Fair Annie of L&hroyan. LONDON: W A R D, LOCK, AND TYLER. WARWICK HOUSE, PATERNOSTER ROW. LOS DOS PRINTKD BY JAS. WAOE, TAVISTOCK STREET, COVBSI GARDEN 10 PREFACE. The subject which we have here treated is a sort of figurative battle-field, where fierce contests have for ages been from time to time waged; and, notwithstanding the determined assaults of the attacking hosts, the contention and its cause remain pretty much as they were at the commencement of the war. We in the matter remain strictly neutral, merely performing the part of the public's " own correspondent," making it our duty to gather together such extracts from despatches, both ancient and modern, as may prove interesting or important, to take note of the vicissitudes of war, mark its various phases, and, in fine, to do our best to lay clearly before our readers the historical facts—experiences and arguments—relating to the much-discussed " Corset question" As most of our readers are aware, the leading journals especially intended for the perusal of ladies have been for many years the media for the exchange of a vast number of letters and papers touching the use of the Corset. The questions relating to the history of this apparently indispensable article of ladies' attire, its construction, application, and influence on the figure have become so numerous of late that we have thought, by embodying all that we can glean and garner relating to Corsets, their wearers, and the various costumes worn by ladies at different periods, arranging the subject-matter in its due order as to dates, and at the same time availing ourselves of careful illustration when needed, that an interesting volume would result. -

Tithe Barn Jericho Farm • Near Cassington • Oxfordshire • OX29 4SZ a Spacious and Exceptional Quality Conversion to Create Wonderful Living Space

Tithe Barn Jericho Farm • Near Cassington • Oxfordshire • OX29 4SZ A spacious and exceptional quality conversion to create wonderful living space Oxford City Centre 6 miles, Oxford Parkway 4 miles (London, Marylebone from 56 minutes), Hanborough Station 3 miles (London, Paddington from 66 minutes), Woodstock 4.5 miles, Witney 7 miles, M40 9/12 miles. (Distances & times approximate) n Entrance hall, drawing room, sitting room, large study kitchen/dining room, cloakroom, utility room, boiler room, master bedroom with en suite shower room, further 3 bedrooms and family bathroom n Double garage, attractive south facing garden n In all about 0.5 acres Directions Leave Oxford on the A44 northwards, towards Woodstock. At the roundabout by The Turnpike public house, turn left signposted Yarnton. Continue through the village towards Cassington and then, on entering Worton, turn right at the sign to Jericho Farm Barns, and the entrance to Tithe Barn will be will be seen on the right after a short distance. Situation Worton is a small hamlet situated just to the east of Cassington with easy access to the A40. Within Worton is an organic farm shop and cafe that is open at weekends. Cassington has two public houses, a newsagent, garden centre, village hall and primary school. Eynsham and Woodstock offer secondary schooling, shops and other amenities. The nearby historic town of Woodstock provides a good range of shops, banks and restaurants, as well as offering the World Heritage landscaped parkland of Blenheim Palace for relaxation and walking. There are three further bedrooms, family bathroom, deep eaves storage and a box room.