Sacpbk1977resizedopt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Guinea Bissau • Zi111bab\Ne ·Na111ibia • South Africa

WINTER. 1975 SOUTHERN AFRICA TODAY •. angola, • IIIOZa111bique ·republic of guinea bissau • zi111bab\Ne ·na111ibia • south africa - the africa fu~ (associated with the American Committee on Africa) 164 Madison Ave. New York, N.Y. 10016 WINTER. 1975 LITERATURE I,IST . ' '~ Please Return Thf.• Order Fo~ With Y~~r Remfttance<,, :J:. $_ Enc:losed is l'lfY remittance (t~C:tudtng 15~ of the total to cover postage and handling charges)· · Please bill us (organf.~t.ions_,_ libraries,. ~kshops) Please send the follOwing --indicate quantity-- 1_ 2 3_ 4_ 5_:_ 6--- 7_ 8~ 9_ 10___ lt_ 12.:.._ 13_ 14_ 15_ 16_ 17 18_ 19_ 20_ 21_ 22 34_ 35_ 36_ 37_ 38_ 39_ 40_ 41 42_ 43_ 44_ 45_ 46 47_ 48_ 49 so_ st_ 52_ 53_ 54 55_ 56_ 57_ 58 59 60 61 62 63_ 64_ 65 66_ 67_ 68_ 69_ 70_ 71_ 72___;_ 73' 74_ 75.;._ 76_ l7.__ 18_;_, 19 80_ 81_ 82_ 83_ 84_ 85_ 86_ 87_ ';., .. To: The Africa Fund 164 Madison Avenue New 'fork, ·NY 10016 · c/o Literature Departaent affiliatioa: ------------------------------------------------- address: _______.__ ________~---------------------~.~"~----~---- city: ___..___....._ _ _.__ state: ------ zip.· cC)cfe: ----- 11: D Enclosed is my contribution of$ ___ for the·work of the committee. ' .,: . The American Committee on Africa, formed in 1953, is the oldest U.S. organization effectively and responsibly supporting African J>eople in th~ir heroic struggie for dignity and freedom. ACO.A is a non-profit organization, ·· with its main purposes being: · · · . • to support policies furthering freedom, self-government and equal rights in Africa • to support projects in Africa promoting these policies • to interpret the meaning of African issues to the American people • to be of assistance to African representatives a,nd students in the U.S. -

A3393-E5-01-Jpeg.Pdf

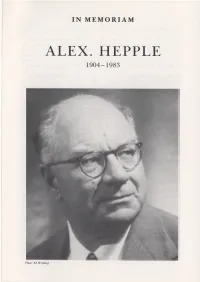

IN MEMORIAM ALEX. HEPPLE 1904-1983 Photo: Eli Weinberg And we, shall we too, crouch and quail, Ashamed, afraid o f strife, And lest our lives untimely fail Embrace the death in life? Nay; cry aloud, and have no fear, We few against the world; Awake, arise! the hope we bear Against the curse is hurled. William Morris, No Master ALEX. HEPPLE 1904-1983 Alex. Hepple died peacefully in Canterbury on 16 November 1983, aged 79. He was leader o f the South African Labour Party (1953—58), founder and chairman o f the Treason Trial Defence Fund (1956—61), and o f the South African Defence and Aid Fund (1960—64). With his wife, Girlie, who was his close comrade in all his activities, he established the International Defence and Aid Fund’s Information Service in 1967 in London, and together they managed the Service until their retirement at the end o f 1972. He was the author o f Verwoerd (Pelican, 1967) and South Africa: a political and economic history (Pall Mall, 1966) as well as numerous pamphlets and articles on political and trade union affairs in South Africa. Alex. Hepple was born in Johannesburg on 28 August 1904. His father, an immigrant from Sunderland, was a militant member and branch secretary o f the Amalgamated Society o f Engineers, and his mother was a strong supporter o f the suffragettes. They were founding members o f the Labour Party, o f which Alex, became a lifelong member in South Africa and later, Britain. Among the formative experiences o f his youth were the victimisation o f his father for his part in the 1913 and 1914 Rand strikes, and the sight o f workers being fired on by Smuts’ troops during the general strike in 1922. -

A3393-E6-5-5-01-Jpeg.Pdf

^HK,fLRS UNbER l\?hKXtfe\ D INTERNATIONAL LABOUR REVIEW Published monthly by the International Labour Office ,e 100 November 1969 Number 5 BOOKS RECEIVED General H epple, Alex. South Africa: workers under apartheid. Published for the International Defence and Aid Fund. London, Christian Action Publica tions Ltd, 1969. vi+86 pp. Tables, bibliographical references. 6s. This pamphlet on the application of the policy of apartheid in the labour field covers essentially the same ground as the ILO’s Special Reports on apartheid. It provides a good general introduction to the subject and includes particularly useful data on wages, job reservation and trade unionism in the Republic of South Africa. The first part outlines the political background of the Government’s policy. This is followed by three parts dealing respectively with the labour force, its racial grading and the various laws designed to control African labour; the labour laws applying to collective bar gaining, wage fixing, the right to strike and the reservation of jobs on a racial basis; and trade unionism and the methods used to curb the unionisation of Africans. The final part refers to the steps taken by the ILO and the United Nations to deal with the labour and trade union situation in the Republic of South Africa. 'TUs- /<J2x/ve^. /t/y/Cf _ Labour dilemma for S may be known, Hepple entitled “South A certain jobs in South Africa: Workers under Africa are reserved for apartheid” and pub whites only—particularly lished by th e Inter racists skilled jobs. But the national Defence and trouble is that there is Aid Fund at six shillings. -

African South Vol. 4, No. 2

African South Vol. 4, No. 2 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.ASJAN60 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org African South Vol. 4, No. 2 Alternative title Africa South Author/Creator Ronald M. Segal; David Marais; Senator Dr. the Hon Leslie Rubin; Stanley Uys; Professor Leo Kuper; Anthony Delius; John Nieuwenhuysen; Phyllis Ntantala; Alex. Hepple; David Miller; Arnold Benjamin; Terence Ranger; John Reed; Vella Pillay; J. M. Nazareth, M.L.C; Philippee Decraene; Lord Altrincham; James Cameron; Dr. A. C. Jordan; Miriam Koshland; -

Class of Their Own: the Bantu Education Act (1953) Revisited

IN A CLASS OF THEIR OWN: THE BANTU EDUCATION ACT (1953) REVISITED. by NADINE LAUREN MOORE Submitted as requirement for the degree MAGISTER HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTIAE (HISTORY) in the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Pretoria 2015 Supervisor: Professor Karen L. Harris Abstract Various political parties, civil rights groups, ministerial spokespeople and columnists support the view that one of South Africa's leading challenges is overcoming the scarring legacy that the Bantu Education Act of 1953 left on the face of the country. In the light of this a need arises to revisit the position and place of Bantu Education in the current contested interpretation of its legacy. It is apparent from the vast literature on this topic that academics are not in agreement about whether or not the 1953 education legislation was the watershed moment for ensuring a cheap labour force. On the one hand it would seem that the general consensus is that 1953 was indeed a turning point in this regard – thus a largely traditional view. However, on the other hand, another school of thought becomes apparent, which states that securing a cheap, unskilled labour force was already on the agenda of the white electorate preceding the formalisation of the Bantu Education Act. This latter school of academics propose that their theory be coined as a “Marxist” one. In examining these two platforms of understanding, traditional and Marxist, regarding Bantu Education and the presumption that it was used as a tool to ensure a cheap, unskilled labour force, the aim of this study is two-fold. First, to contextualise these two stances historically; and second to examine the varying approaches regarding the rationalisation behind Bantu Education respectively by testing these against the rationale apparent in the architects of the Bantu Education system. -

Interview with Hilda Watts and Rusty Bernstein Part 1

Ruth First Papers project I Interview with Hilda Watts and Rusty Bernstein part 1 An interview conducted by Don Pinnock c. 1992. Part of a series carried out at Grahamstown University and held at the UWC/Robben Island Mayibuye Archive. Republished in 2012 by the Ruth First Papers Project www.ruthfirstpapers.org.uk RB: ... that's right, I saw that term - somebody wrote an article about the when-we's that I was reading recently. Can't remember where. HW: Yes, there was a wonderful little play about Rhodesians on the television. I can't remember the name of the man who wrote it. RB: It was called something Road ... Salisbury Road. HW: Salisbury Road, that's right. It was about a white Rhodesian left in his job when the when-we's have gone because he's older and hasn't any real alternatives, and a black boss is appointed above him. He and his - one son has left the country, and the other son was killed or something – RB: The other son was called up for military service at the end of the play and refused to go. HW: No, he was the one who left ... DP: I want to put this together this morning. I wanted to get a feeling of when you were involved in the CP so I know how far back to ask you questions. Before the war, or during? RB: Before the war. I think Hilda probably earlier than me. HW: Ja, I joined the Communist Party in 1935 in Britain. I went to South Africa about 1937. -

The African Patriots, the Story of the African National Congress of South Africa

The African patriots, the story of the African National Congress of South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The African patriots, the story of the African National Congress of South Africa Author/Creator Benson, Mary Publisher Faber and Faber (London) Date 1963 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 968 B474a Description This book is a history of the African National Congress and many of the battles it experienced. -

Africa South Vol. 1, No. 1

Africa South Vol. 1, No. 1 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.ASOCT56 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Africa South Vol. 1, No. 1 Alternative title Africa South Author/Creator Ronald M. Segal; Right Rev. R. A. Reeves, Bishop of Johannesburg; J. P. Du P. Basson, M.P.; Vicky; Dr. Helen Hellmann; Alex Hepple, M.P.; J. W. Macquarrie; Leo L. Sihlali; Dr. H. J. Simons; Stanley Uys; Jordan K. Nguhane; Patrick Duncan; Dr. George W. Shepherd, Jr.; Fenner Brockway, M.P.; Desmond Buckle; John Hatch; Harry Bloom; Guy Butler Date -

A3393-E6-7-3-2-01-Jpeg.Pdf

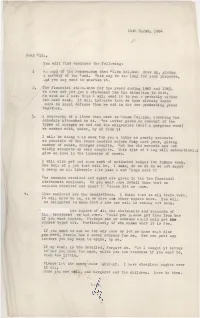

14th Marsh, 1964 Dear -^ili, You will find enclosed the following: 1 An copy of the Memorandum that ^lien Heilman drew up, giving a history of the ^'und. i-his may be too long for your purposes, and you may want to shorten it. 2. The financial statements for the years ending 1962 and 1963. We have not yet got a statement for the situation to date. As soon as I have this will send it to you - probably within the next week. It will indicate that we have already spent more on legal defence than we did in the two predeeding years together. 3. A near—copy of a ltter that went to Danon ^olxins, covering the schedule attanched to it. 1he letter gives an account of the types of charges we had and the exigencies (what a gorgeous word) we worked with, under, by or from \\ I will be doing tc.is week for you a table as nearly accurate as possible of the cases handled before Juhy last year, giving number of cases, charges results, ^ut the old records are not wildly accurate or very complete. This type of t ing will automatically give an idea in the increase of cases. I will also get out some sort of estimated budget for future work. One heli of a job that will be. I mean, do we do do we not expct a swoop on alx Liberals this yeqr - and ■‘•"rogs next ?? II he amounts received and spent are given in the two finaicial statements enclosed. Do you want more detail than that on amounts received and spent ? Please let me snow. -

Richard Ambrose Reeves: Bishop of Johannesburg, 1949 to 1961

RICHARD AMBROSE REEVES: BISHOP OF JOHANNESBURG, 1949 TO 1961 by FRANK DONALD PHILLIPS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR G C CUTHBERTSON JOINT SUPERVISOR: PROF A L HARINGTON JUNE 1995 Student number: 436-180-6 I declare that * .. ii.ICHA ?..D AI-I:BkWS~ REEVES:. BISHO] _QF .. _JOI'L'il-:H~S::::-URJ, 1949 . ..TO. I9.6I...................... is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ... :~ ..r:J/ 1.Y. /1.9.~. sZP.fa(~.{+. · DATE (REV F D PHILLIPS) * The exact wording of the title as it appears on the copies of your dissertation, submitted for examination purposes, should be indicated in the open space. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements i summary ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 BEFORE JOHANNESBURG 22 CHAPTER 2 THE GOD-PERSON RELATIONSHIP 51 CHAPTER 3 SOCIAL AND POLITICAL RECONCILIATION 74 CHAPTER 4 THE OPPONENT OF APARTHEID 97 CHAPTER 5 BANTU EDUCATION DEFIED 126 CHAPTER 6 SOCIAL ACTION: HOUSING AND THE TREASON TRIAL 147 CHAPTER 7 REEVES AND SHARPEVILLE 175 CONCLUSION 209 SOURCE LIST 216 Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the untiring help given me by Anna Cunningham, Michele Pickover, and the staff at the Church of the Province Archives housed in the William Cullen Library of the University of the Witwatersrand. Joy Leslie-Smith of the Alan Paton Centre of the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg has been wonderfully supportive in my project. -

Vol. 2 No. 1 Oct.-Dec.195

SOUTH Vol. 2 No. 1 Oct.-Dec.195: Special Features THE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE By Harry Bloom THE PRESS: STRIJDOM'S LAST BARI By George Clay and Stanley Uys THE CHALLENGE OF FEDERATION By The Rt. Hon. A. Creech Jones, P.C, M.P. THE UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA 3/9 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 75c GREAT BRITAIN AND AFRICA 4/- INDIA AND CEYLON Rs. 2.50 ISBKHBHHBnnBIWl VOL. 2 No. 1 EDITOR: RONALD M. SEGAL OCT.—DEC. 1957 CONTENTS THE PRISONERS by Gerard Sekoto _____ Frontispiece SEX AND SEDITION __-__-__ i THE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE by Harry Bloom - 8 CARTOON by David Marais - - - - - - - 19 THE PRESS: STRIJDOM'S "LAST BARRIER" by George Clay and Stanley Uys 21 RACE ZONING IN CLOUD CUCKOO LAND by Leo Kuper - - 33 THE GHETTO ACT by Yusuf Cachalia - - - - - - 39 THE SCHIZOPHRENIC HEART by Dr. 0. D. Wollheim 45 THE TRIAL TAKES SHAPE by Tony CTDowd - - - - - ci A DAY TO REMEMBER by Christopher Gell ----- 5-4 PORTRAIT OF A SUBURB: HILLBROW by Arnold Benjamin - - 57 SOUTH WEST AFRICA by Jariretundu Kozonguizi - - - - 64 THE CHALLENGE OF FEDERATION by the Rt. Hon. A. Creech Jones, P.C., M.V. 73 KAMPALA DIARY by M. M. Carlin - - - - - - 84 ISKAEL AND AFRICA by E. Ben-Horin - - - - - - 90 TOWARDS AN AFRICAN LITERATURE (II) by Dr. A. C. Jordan 97 ANGLO-SAXON DREAMS by Michael Picardie - - - - - 106 HIGH FENCE by Michael Fisher - - - - - - 107 TENNANT STREET, CAPE TOWN by William Papas - - - 117 OUT OF THE DARKNESS by Alex La Guma - - - - -118 BOOK REVIEWS by Julius Lewin, Ray Alexander, J. D. -

91 Hendrik Verwoerd and the Leipzig School of Psychology in 1926

Historia 58, 2, November 2013, pp 91-118 Hendrik Verwoerd and the Leipzig School of Psychology in 1926 Christoph Marx In his groundbreaking book The Rise of Afrikanerdom, the sociologist Dunbar Moodie claims that a number of young Afrikaner intellectuals, and Hendrik Verwoerd in particular, were imbued with “neo-Fichtean” nationalism while at university in Germany in the 1920s. Moodie traces German radical cultural nationalism back to the teachings of the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, especially to his Reden an die Deutsche Nation (Addresses to the German nation), delivered during the wars against Napoleon.1 Although never actually substantiated by Moodie, this claim has been treated as an established fact ever since.2 However, my research has shown that there is no evidence of this and until such time as new documentary evidence is found, Moodie’s claim will remain nothing more than a plausible-sounding theory. Moreover, even if traces of such influence were to be found, they would only confirm that Verwoerd was a nationalist from his school days, long before his arrival in Germany.3 It is not self-evident that he would have been exposed to radical nationalism during his stay in Germany. The Weimar Republic was in a phase of political stabilisation in 1926 and not on the verge of collapse, as alleged by Alex Hepple, nor was the Nazi dictatorship foreseeable.4 It is necessary to take a close look at where, when and with whom Verwoerd studied in Germany. The University of Witwatersrand psychiatrist, Alban Burke, has gone so far as to name certain racist academics and eugenics specialists that Verwoerd allegedly met and communicated with during his stay in Germany but provides no evidence for this.5 My own research in the archives has produced nothing to corroborate Burke’s allegations – on the contrary.