African South Vol. 4, No. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Throughout the 1950S the Liberal Party of South Africa Suffered Severe Internal Conflict Over Basic Issues of Policy and Strategy

Throughout the 1950s the Liberal Party of South Africa suffered severe internal conflict over basic issues of policy and strategy. On one level this stemmed from the internal dynamics of a small party unequally divided between the Cape, Transvaal and Natal, in terms of membership, racial composftion and political traditon. This paper and the larger work from which it is taken , however, argue inter alia that the conflict stemmed to a greater degree from a more fundamental problem, namely differing interpretations of liberalism and thus of the role of South African liberals held by various elements within the Liberal Party (LP). This paper analyses the political creed of those parliamentary and other liberals who became the early leaders of the LP. Their standpoint developed in specific circumstances during the period 1947-1950, and reflected opposition to increasingly radical black political opinion and activity, and retreat before the unfolding of apartheid after 1948. This particular brand of liberalism was marked by a rejection of extra- parliamentary activity, by a complete rejection of the univensal franchise, and by anti-communism - the negative cgaracteristics of the early LP, but also the areas of most conflict within the party. The liberals under study - including the Ballingers, Donald Molteno, Leo Marquard, and others - were all prominent figures. All became early leaders of the Liberal Party in 1953, but had to be *Ihijackedffigto the LP by having their names published in advance of the party being launched. The strategic prejudices of a small group of parliamentarians, developed in the 1940s, were thus to a large degree grafted on to non-racial opposition politics in the 1950s through an alliance with a younger generation of anti-Nationalists in the LP. -

The Referendum in FW De Klerk's War of Manoeuvre

The referendum in F.W. de Klerk’s war of manoeuvre: An historical institutionalist account of the 1992 referendum. Gary Sussman. London School of Economics and Political Science. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and International History, 2003 UMI Number: U615725 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615725 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h e s e s . F 35 SS . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract: This study presents an original effort to explain referendum use through political science institutionalism and contributes to both the comparative referendum and institutionalist literatures, and to the political history of South Africa. Its source materials are numerous archival collections, newspapers and over 40 personal interviews. This study addresses two questions relating to F.W. de Klerk's use of the referendum mechanism in 1992. The first is why he used the mechanism, highlighting its role in the context of the early stages of his quest for a managed transition. -

Republic of Guinea Bissau • Zi111bab\Ne ·Na111ibia • South Africa

WINTER. 1975 SOUTHERN AFRICA TODAY •. angola, • IIIOZa111bique ·republic of guinea bissau • zi111bab\Ne ·na111ibia • south africa - the africa fu~ (associated with the American Committee on Africa) 164 Madison Ave. New York, N.Y. 10016 WINTER. 1975 LITERATURE I,IST . ' '~ Please Return Thf.• Order Fo~ With Y~~r Remfttance<,, :J:. $_ Enc:losed is l'lfY remittance (t~C:tudtng 15~ of the total to cover postage and handling charges)· · Please bill us (organf.~t.ions_,_ libraries,. ~kshops) Please send the follOwing --indicate quantity-- 1_ 2 3_ 4_ 5_:_ 6--- 7_ 8~ 9_ 10___ lt_ 12.:.._ 13_ 14_ 15_ 16_ 17 18_ 19_ 20_ 21_ 22 34_ 35_ 36_ 37_ 38_ 39_ 40_ 41 42_ 43_ 44_ 45_ 46 47_ 48_ 49 so_ st_ 52_ 53_ 54 55_ 56_ 57_ 58 59 60 61 62 63_ 64_ 65 66_ 67_ 68_ 69_ 70_ 71_ 72___;_ 73' 74_ 75.;._ 76_ l7.__ 18_;_, 19 80_ 81_ 82_ 83_ 84_ 85_ 86_ 87_ ';., .. To: The Africa Fund 164 Madison Avenue New 'fork, ·NY 10016 · c/o Literature Departaent affiliatioa: ------------------------------------------------- address: _______.__ ________~---------------------~.~"~----~---- city: ___..___....._ _ _.__ state: ------ zip.· cC)cfe: ----- 11: D Enclosed is my contribution of$ ___ for the·work of the committee. ' .,: . The American Committee on Africa, formed in 1953, is the oldest U.S. organization effectively and responsibly supporting African J>eople in th~ir heroic struggie for dignity and freedom. ACO.A is a non-profit organization, ·· with its main purposes being: · · · . • to support policies furthering freedom, self-government and equal rights in Africa • to support projects in Africa promoting these policies • to interpret the meaning of African issues to the American people • to be of assistance to African representatives a,nd students in the U.S. -

SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE of RACE RELATIONS 79Th ANNUAL

SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS 79th ANNUAL REPORT 1st JANUARY TO 31st DECEMBER 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS, 9th FLOOR, RENAISSANCE CENTRE, GANDHI SQUARE, 16–20 NEW STREET SOUTH, JOHANNESBURG, 2001 SOUTH AFRICA COMPANY REGISTRATION NUMBER: 1937/010068/08 NON-PROFIT REGISTRATION NUMBER: 000-709-NPO PUBLIC BENEFIT ORGANISATION NUMBER: 930006115 Private Bag X13, Marshalltown, 2107 South Africa Telephone: (011) 492-0600 Telefax: (011) 492-0588 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.sairr.org.za ISBN 978-1-86982-580-5 PD 11/2009 Printed by Ince (Pty) Ltd Cover design by lime design Our front cover, using a photograph from the Sunday Times (photogra - pher James Oatway), depicts the chief justice, Judge Pius Nkonzo Langa, administering the oath of office to President Jacob Zuma dur - ing his inauguration at the Union Buildings in Pretoria on 9th May 2009. The back cover features Mrs Helen Suzman taken in 1990 in her study at home. The photograph is from Gallo Images (South Photographs). COUNCIL President : Professor Jonathan Jansen Immediate Past President : Professor Sipho Seepe Vice Presidents : Professor Hermann Giliomee Professor Lawrence Schlemmer Dr Musa Shezi Chairman of the Board of Directors : Professor Charles Simkins Honorary Treasurer : Mr Brian Hawksworth Honorary Legal Adviser : Mr Derek Bostock Representatives of Members: Honorary Life : Mr Benjy Donaldson Professor Elwyn Jenkins Individual Gauteng : Mr Francis Antonie Mr Jack Bloom MPL Professor Tshepo Gugushe Mr Peter Joubert -

A History of the Progressive Federal Party, 1981 - 1989

STRUCTURAL CRISIS AND LIBERALISM: A HISTORY OF THE PROGRESSIVE FEDERAL PARTY, 1981 - 1989 DAVID SHANDLER Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Economic History, Faculty of Arts, University of Cape Town, January 1991 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. .ABSTRACT Whereas an extensive literature has developed on the broad conditions of crisis in South Africa in the seventies and eighties, and on the dynamic of state and popular responses to it, little focus has fallen .on the reactions . of the other key elements among the dominating classes. It is the aim of this dissertation to attempt to address an aspect of this lacuna by focussing on the Progressive Federal Party's responses from 1981 until 1989. The thesis develops an understanding of the period as one entailing conditions of organ.le crisis. It attempts to show the PFP' s behaviour in the context of structural and conjunctural crises. The thesis periodises the Party's policy and strategic responses and makes an effort to show its contradictory nature. An effort is made to understand this contradictory character in terms of the party's class location with respect to the white dominating classes and leading elements within it; in relation to the black dominated classes; as well as in terms of the liberal tradition within which the Party operated. -

![The Preview Edition [PDF] Here](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6005/the-preview-edition-pdf-here-1066005.webp)

The Preview Edition [PDF] Here

Humanistic Judaism Magazine Helen Suzman 2021–2022 Humanistic Jewish Role Model Diagnosis: Casteism by Rabbi Jeffrey Falick Challenging the Phrase "Judeo-Christian Values" by Lincoln Dow A Woman of Valor for the Ages by Marilyn Boxer Community News and much more Spring 2021 Table of Contents From the Editor Tributes, Board of Directors, p. 3 Communities p. 21–22 Humanism Can Lead to the Future Acceptance of Tolerance and Human Unity p. 4, 20 Contributors I Marilyn J. Boxer is secretary and program co-chair at by Professor Mike Whitty Kol Hadash in Berkeley, California. She is also professor emerita of history and former vice-president/provost at San Helen Suzman Francisco State University. p. 5–6 I Lincoln Dow is the Community Organizer of Jews for a Secular Democracy, a pluralistic initiative of the Society for A Woman of Valor for the Ages Humanistic Judaism. He studies politics and public policy by Marilyn Boxer at New York University. I Rachel Dreyfus is the Partnership & Events Coordinator “I Was Just Doing My Job” for the Connecticut CHJ. I Jeffrey Falick is the Rabbi of The Birmingham Temple, p. 7–8 Congregation for Humanistic Judaism. Interviews with Paul Suzman and Frances Suzman Jowell I K. Healan Gaston is Lecturer on American Religious by Dan Pine History and Ethics at Harvard Divinity School and the author of Imagining Judeo-Christian America: Religion, Imagining Judeo-Christian America Secularism, and the Redefinition of Democracy (University of Chicago Press, 2019). She is currently completing p. 9, 18 Beyond Prophetic Pluralism: Reinhold and H. Richard Book Excerpt by K. -

Colin Eglin, the Progressive Federal Party and the Leadership of the Official Parliamentary Opposition, 1977‑1979 and 1986‑1987

Journal for Contemporary History 40(1) / Joernaal vir Eietydse Geskiedenis 40(1): 1‑22 © UV/UFS • ISSN 0285‑2422 “ONE OF THE ARCHITECTS OF OUR DEMOCRACY”: COLIN EGLIN, THE PROGRESSIVE FEDERAL PARTY AND THE LEADERSHIP OF THE OFFICIAL PARLIAMENTARY OPPOSITION, 1977‑1979 AND 1986‑1987 FA Mouton1 Abstract The political career of Colin Eglin, leader of the Progressive Federal Party (PFP) and the official parliamentary opposition between 1977‑1979 and 1986‑1987, is proof that personality matters in politics and can make a difference. Without his driving will and dogged commitment to the principles of liberalism, especially his willingness to fight on when all seemed lost for liberalism in the apartheid state, the Progressive Party would have floundered. He led the Progressives out of the political wilderness in 1974, turned the PFP into the official opposition in 1977, and picked up the pieces after Frederik van Zyl Slabbert’s dramatic resignation as party leader in February 1986. As leader of the parliamentary opposition, despite the hounding of the National Party, he kept liberal democratic values alive, especially the ideal of incremental political change. Nelson Mandela described him as, “one of the architects of our democracy”. Keywords: Colin Eglin; Progressive Party; Progressive Federal Party; liberalism; apartheid; National Party; Frederik van Zyl Slabbert; leader of the official parliamentary opposition. Sleutelwoorde: Colin Eglin; Progressiewe Party; Progressiewe Federale Party; liberalisme; apartheid; Nasionale Party; Frederik van Zyl Slabbert; leier van die amptelike parlementêre opposisie. 1. INTRODUCTION The National Party (NP) dominated parliamentary politics in the apartheid state as it convinced the majority of the white electorate that apartheid, despite the destruction of the rule of law, was a just and moral policy – a final solution for the racial situation in the country. -

Professional Historians and Political Biography of South African Parliamentary Politics, 1910-1990

“THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY”: PROFESSIONAL HISTORIANS AND POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF SOUTH AFRICAN PARLIAMENTARY POLITICS, 1910-1990 FA Mouton1 Abstract Biography strengthens the historian’s attempts to decipher the behaviour of individuals and also provides a historical window on a certain era, contributing to our knowledge and understanding of the past. Biographical studies of those who were involved in parliamentary politics between 1910 and 1990, the prime ministers, presidents, cabinet ministers, party leaders, humble backbenchers and unsuccessful parliamentary candidates can help to explain why the white minority, after decades of acquiescing the abuse of South Africa’s limited democratic tradition, decided to peacefully surrender its political power. And yet, despite the proven value of political biography in the United States and Britain, the library shelves of South African universities are bare of biographies on pre-1990 parliamentary politicians by professional historians. This article explains the reasons for this dearth of biographies, as well as the reasons why it is essential for professional historians to write them and concludes with a recommendation on how such biographies should be written. 1. INTRODUCTION By deciphering the behaviour of individuals, providing in the process a historical window on societies of the past, the historian as biographer plays a crucial role to convey knowledge and understanding of our history to the reading public. Biographical studies of the lives and careers of parliamentary politicians between 1910 and 1990 are for example essential to comprehend South African history in the twentieth century. And yet, despite the internationally proven value of biography, the library shelves of South African universities are bare of biographies by professional historians on pre-1990 parliamentary history. -

A3393-E5-01-Jpeg.Pdf

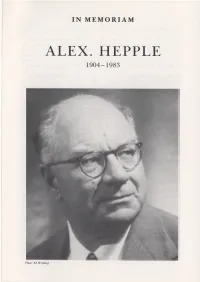

IN MEMORIAM ALEX. HEPPLE 1904-1983 Photo: Eli Weinberg And we, shall we too, crouch and quail, Ashamed, afraid o f strife, And lest our lives untimely fail Embrace the death in life? Nay; cry aloud, and have no fear, We few against the world; Awake, arise! the hope we bear Against the curse is hurled. William Morris, No Master ALEX. HEPPLE 1904-1983 Alex. Hepple died peacefully in Canterbury on 16 November 1983, aged 79. He was leader o f the South African Labour Party (1953—58), founder and chairman o f the Treason Trial Defence Fund (1956—61), and o f the South African Defence and Aid Fund (1960—64). With his wife, Girlie, who was his close comrade in all his activities, he established the International Defence and Aid Fund’s Information Service in 1967 in London, and together they managed the Service until their retirement at the end o f 1972. He was the author o f Verwoerd (Pelican, 1967) and South Africa: a political and economic history (Pall Mall, 1966) as well as numerous pamphlets and articles on political and trade union affairs in South Africa. Alex. Hepple was born in Johannesburg on 28 August 1904. His father, an immigrant from Sunderland, was a militant member and branch secretary o f the Amalgamated Society o f Engineers, and his mother was a strong supporter o f the suffragettes. They were founding members o f the Labour Party, o f which Alex, became a lifelong member in South Africa and later, Britain. Among the formative experiences o f his youth were the victimisation o f his father for his part in the 1913 and 1914 Rand strikes, and the sight o f workers being fired on by Smuts’ troops during the general strike in 1922. -

Helen Zille and the Struggle for Liberation

POLITICS © TNA ManufaCTURING FONG-KONG HISTORY Helen Zille and the Struggle for Liberation Zille’s distortions are founded on a theory conveniently crafted to inflate the importance of the DA and exaggerate the contribution of conservative liberals to the struggle for freedom. By Eddy Maloka he public anger over the abuse She cited what the PP’s first leader, lines of the Freedom Charter: “We, of history by the Democratic Jan Steytler, once said in 1959: “In the People of South Africa, declare for TAlliance (DA) is expected. But future, colour and colour alone should all our country and the world to know DA leader Helen Zille has been in the not be the yardstick by which people that South Africa belongs to all who business of manufacturing fong-kong are judged”; and made a startling claim: live in it, black and white, and that no history of the struggle for some time; “In the iron grip of apartheid, this was government can justly claim authority it’s only that she has gotten away with radical, subversive even, coming from unless it is based on the will of all the this in the past. An example is her a white South African. In fact, today we people”. speech delivered in November 2009 at look back on Jan Steytler's words and Furthermore, what Zille failed a function to commemorate the 50th realise that he was more than 50 years to mention about the PP is that it anniversary of the Progressive Party ahead of his time”. represented a conservative brand of (PP) which is full of distortions and in This is not true. -

Helen Suzman, the Liberal Member of the Old South African Parliament

Helen suzman AN AppreciatIoN Helen Suzman, the liberal member of the old South African parliament, renowned for her courageous and unrelenting fight for human rights and justice, died peacefully in her home in Johannesburg in the small hours of New Year’s Day 2009. Her Liberalism was more than a political creed; it was a state of mind, a way of life, a responsibility towards others. Colin Eglin, a co-founder of the anti- apartheid Progressive Party, recalls her. 32 Journal of Liberal History 66 Spring 2010 Helen suzman AN AppreciatIoN he expressions of grief judiciary, transparent governance, invested in land, property and at her death, of respect and an open society in which other businesses for her person, and of individuals would be free to make Samuel Gavronsky, wanting gratitude for her life choices. She campaigned for the the best available schooling for his and her service that abolition of the death penalty. She two daughters, arranged for Helen Tcame from all sections of the fought for human rights. and her sister Gertrude to go to South African people and from During the dark days of apart- Parktown Convent, a Catholic representatives all political par- heid she did more than any other school for girls. Upon complet- ties were testimony to the impact person to keep liberal values ing her schooling Helen enrolled she had made on the politics of alive. Indeed, South Africa’s new at Witwatersrand University to South Africa and on the lives of its democratic constitution, with the study for the degree of Bachelor of citizens. -

A3393-E6-5-5-01-Jpeg.Pdf

^HK,fLRS UNbER l\?hKXtfe\ D INTERNATIONAL LABOUR REVIEW Published monthly by the International Labour Office ,e 100 November 1969 Number 5 BOOKS RECEIVED General H epple, Alex. South Africa: workers under apartheid. Published for the International Defence and Aid Fund. London, Christian Action Publica tions Ltd, 1969. vi+86 pp. Tables, bibliographical references. 6s. This pamphlet on the application of the policy of apartheid in the labour field covers essentially the same ground as the ILO’s Special Reports on apartheid. It provides a good general introduction to the subject and includes particularly useful data on wages, job reservation and trade unionism in the Republic of South Africa. The first part outlines the political background of the Government’s policy. This is followed by three parts dealing respectively with the labour force, its racial grading and the various laws designed to control African labour; the labour laws applying to collective bar gaining, wage fixing, the right to strike and the reservation of jobs on a racial basis; and trade unionism and the methods used to curb the unionisation of Africans. The final part refers to the steps taken by the ILO and the United Nations to deal with the labour and trade union situation in the Republic of South Africa. 'TUs- /<J2x/ve^. /t/y/Cf _ Labour dilemma for S may be known, Hepple entitled “South A certain jobs in South Africa: Workers under Africa are reserved for apartheid” and pub whites only—particularly lished by th e Inter racists skilled jobs. But the national Defence and trouble is that there is Aid Fund at six shillings.