A Po Litical History of the Congress Alliance in South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claiming Independence in 140 Characters. Uses of Metaphor in the Construction of Scottish and Catalan Political Discourses on Twitter

CLAIMING INDEPENDENCE IN 140 CHARACTERS. USES OF METAPHOR IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF SCOTTISH AND CATALAN POLITICAL DISCOURSES ON TWITTER Carlota Maria Moragas Fernández ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. -

African Presses, Christian Rhetoric, and White Minority Rule in South Africa, 1899-1924

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 For the Good That We Can Do: African Presses, Christian Rhetoric, and White Minority Rule in South Africa, 1899-1924 Ian Marsh University of Central Florida Part of the African History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Marsh, Ian, "For the Good That We Can Do: African Presses, Christian Rhetoric, and White Minority Rule in South Africa, 1899-1924" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5539. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5539 FOR THE GOOD THAT WE CAN DO: AFRICAN PRESSES, CHRISTIAN RHETORIC, AND WHITE MINORITY RULE IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1899-1924 by IAN MARSH B.A. University of Central Florida, 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 Major Professor: Ezekiel Walker © 2017 Ian Marsh ii ABSTRACT This research examines Christian rhetoric as a source of resistance to white minority rule in South Africa within African newspapers in the first two decades of the twentieth-century. Many of the African editors and writers for these papers were educated by evangelical protestant missionaries that arrived in South Africa during the nineteenth century. -

A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays. Bonny Ball Copenhaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copenhaver, Bonny Ball, "A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 632. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/632 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis by Bonny Ball Copenhaver May 2002 Dr. W. Hal Knight, Chair Dr. Jack Branscomb Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Russell West Keywords: Gender Roles, Feminism, Modernism, Postmodernism, American Theatre, Robbins, Glaspell, O'Neill, Miller, Williams, Hansbury, Kennedy, Wasserstein, Shange, Wilson, Mamet, Vogel ABSTRACT The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays by Bonny Ball Copenhaver The purpose of this study was to describe how gender was portrayed and to determine how gender roles were depicted and defined in a selection of Modern and Postmodern American plays. -

John Dube Struggle for Freedom(S) in South Africa

SWINGING BETWEEN BILLIGERENCE AND SERVILITY: JOHN DUBE’S STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM(S) IN SOUTH AFRICA Simanga Kumalo Ministry Education and Governance Program, School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu Natal, Scottsville, South Africa Abstract John Langalibalele Mafukuzela Dube left an indelible legacy in South Africa’s political, educational and religious spheres. He was a church leader, veteran politician, journalist, philanthropist and educationist. He was the first President of the African National Congress (ANC) when it was formed in Bloemfontein on January 8, 1912 as the South African National Native Congress (SANNC). Dube was also the founder of the first Zulu newspaper ILanga laseNatali through which he published the experiences of African people under white rule. As the first president of what was to become Africa’s most influential political and liberation movement, Dube served as an ordained minister of the Congregational Church. This important connection helped Dube define church-state relations in colonial South Africa, thus forging the role that African clergy would later need to play in the struggle for South Africa’s freedom and democracy. Although his work influenced various aspects of African people’s lives such as the social, political, educational and economic, he firmly located himself in the church as a pastor and Christian activist whose vocation was to struggle for all the freedoms that were denied to his people, including freedom of religion. This study offers a brief profile of John Dube as a political theologian and highlights his contribution to the struggle of African people for the freedom from colonial and white rule. -

Republic of Guinea Bissau • Zi111bab\Ne ·Na111ibia • South Africa

WINTER. 1975 SOUTHERN AFRICA TODAY •. angola, • IIIOZa111bique ·republic of guinea bissau • zi111bab\Ne ·na111ibia • south africa - the africa fu~ (associated with the American Committee on Africa) 164 Madison Ave. New York, N.Y. 10016 WINTER. 1975 LITERATURE I,IST . ' '~ Please Return Thf.• Order Fo~ With Y~~r Remfttance<,, :J:. $_ Enc:losed is l'lfY remittance (t~C:tudtng 15~ of the total to cover postage and handling charges)· · Please bill us (organf.~t.ions_,_ libraries,. ~kshops) Please send the follOwing --indicate quantity-- 1_ 2 3_ 4_ 5_:_ 6--- 7_ 8~ 9_ 10___ lt_ 12.:.._ 13_ 14_ 15_ 16_ 17 18_ 19_ 20_ 21_ 22 34_ 35_ 36_ 37_ 38_ 39_ 40_ 41 42_ 43_ 44_ 45_ 46 47_ 48_ 49 so_ st_ 52_ 53_ 54 55_ 56_ 57_ 58 59 60 61 62 63_ 64_ 65 66_ 67_ 68_ 69_ 70_ 71_ 72___;_ 73' 74_ 75.;._ 76_ l7.__ 18_;_, 19 80_ 81_ 82_ 83_ 84_ 85_ 86_ 87_ ';., .. To: The Africa Fund 164 Madison Avenue New 'fork, ·NY 10016 · c/o Literature Departaent affiliatioa: ------------------------------------------------- address: _______.__ ________~---------------------~.~"~----~---- city: ___..___....._ _ _.__ state: ------ zip.· cC)cfe: ----- 11: D Enclosed is my contribution of$ ___ for the·work of the committee. ' .,: . The American Committee on Africa, formed in 1953, is the oldest U.S. organization effectively and responsibly supporting African J>eople in th~ir heroic struggie for dignity and freedom. ACO.A is a non-profit organization, ·· with its main purposes being: · · · . • to support policies furthering freedom, self-government and equal rights in Africa • to support projects in Africa promoting these policies • to interpret the meaning of African issues to the American people • to be of assistance to African representatives a,nd students in the U.S. -

Voyages & Travel 1515

Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. CONTENTS Africa . 1 Egypt, The Near East & Middle East . 22 Europe, Russia, Turkey . 39 India, Central Asia & The Far East . 64 Australia & The Pacific . 91 Cover illustration; item 48, Walters . Central & South America . 115 MAGGS BROS. LTD. North America . 134 48 BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON WC1B 3DR Telephone: ++ 44 (0)20 7493 7160 Alaska & The Poles . 153 Email: [email protected] Bank Account: Allied Irish (GB), 10 Berkeley Square London W1J 6AA Sort code: 23-83-97 Account Number: 47777070 IBAN: GB94 AIBK23839747777070 BIC: AIBKGB2L VAT number: GB239381347 Prices marked with an *asterisk are liable for VAT for customers in the UK. Access/Mastercard and Visa: Please quote card number, expiry date, name and invoice number by mail, fax or telephone. EU members: please quote your VAT/TVA number when ordering. The goods shall legally remain the property of the seller until the price has been discharged in full. © Maggs Bros. Ltd. 2021 Design by Radius Graphics Printed by Page Bros., Norfolk AFRICA Remarkable Original Artworks 1 BATEMAN (Charles S.L.) Original drawings and watercolours for the author’s The First Ascent of the Kasai: being some Records of service Under the Lone Star. A bound volume containing 46 watercolours (17 not in vol.), 17 pen and ink drawings (1 not in vol.), 12 pencil sketches (3 not in vol.), 3 etchings, 3 ms. charts and additional material incl. newspaper cuttings, a photographic nega- tive of the author and manuscript fragments (such as those relating to the examination and prosecution of Jao Domingos, who committed fraud when in the service of the Luebo District). -

Fighting Talk, Vol. 10, No. 4, May 1954

Fighting talk, Vol. 10, No. 4, May 1954 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org/. Page 1 of 19 Alternative title Fighting talk Author/Creator Fighting Talk Committee (Johannesburg) Contributor First, Ruth Publisher Fighting Talk Committee (Johannesburg) Date 1954-05 Resource type Newspapers Language Afrikaans, English Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1954 Source Digital Imaging South Africa (DISA) Rights By kind permission of the Fighting Talk Committee. Description Comment. Trade Unions Last Chance, by M. Muller. Poem. Who Will Protect the Protectorates? Red Herrings by Ben Giles. Ray Alexander by J. Podbrey. National Women's Conference by Hilda Watts and Paul Joseph. -

Remembering Ahmed Kathrada, South Africa&

Remembering Ahmed Kathrada, South Africa’s National Liberation Icon Former political prisoner served time for political work alongside Nelson Mandela and others By Abayomi Azikiwe Region: sub-Saharan Africa Global Research, March 31, 2017 Theme: History, Police State & Civil Rights, Poverty & Social Inequality Funeral services were held on March 29 for Ahmed Mohamed “Kathy” Kathrada, a longtime member of the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa. Kathrada died at the age of 87 after undergoing neurosurgery. His memorial was attended by hundreds of family members and friends who paid tribute to the veteran of the decades- long national liberation struggle that brought the ANC to power in 1994. Born on August 21, 1929 to Indian immigrant parents living in the Western Transvaal (now the North West Province), Kathrada was subjected to discriminatory practices of the racist system then dominated by the British with the Boers playing a supplementary role. Coming from the Indian population in the settler-colonial state of the former Union of South Africa, Kathrada played an instrumental role in forming coalitions among the oppressed national groups across the country during the 1940s and 1950s. In 1941, at the age of 12, he joined the Young Communist League, an affiliate of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). He was heavily influenced byDr. Yusuf Dadoo, a leading member of the Indian Congress movement and the Communist Party. Dadoo was an important figure in the Non-European United Front (NEUF) which initially opposed African and Indian involvement in the military services during the early phase of World War II. -

Animal Liberation Currents

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Animal Activism and Interspecies Change Challenging anthropocentrism in politics and liberation activism means understanding animal agency and forms of resistance Meijer, E. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Meijer, E. (Author). (2016). Animal Activism and Interspecies Change: Challenging anthropocentrism in politics and liberation activism means understanding animal agency and forms of resistance. Web publication/site https://www.animalliberationcurrents.com/animal- activism-interspecies-change/ General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep -

National Liquor Authority Register

NATIONAL LIQUOR AUTHORITY REGISTER - 30 JUNE 2013 Registration Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Transfer & (or) Date of Number Permitted Registration Relocations Cancellation RG 0006 The South African Breweries Limited Sab -(Gauteng) M & D 3 Fransen Str, Chamber GP 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0007 Greytown Liquor Distributors Greytown Liquor Distributors D Lot 813, Greytown, Durban KZN 2005/02/25 N/A N/A RG 0008 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Groblersdal) D 16 Linbri Avenue, Groblersdal, 0470 MPU N/A 28/01/2011 RG 0009 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Ga D Stand 14, South Street, Ga-Rankuwa, 0208 NW N/A 27/09/2011 Rankuwa) RG 0010 The South African Breweries Limited Sab (Port Elizabeth) M & D 47 Kohler Str, Perseverence, Port Elizabeth EC 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0011 Lutzville Vineyards Ko-Op Ltd Lutzville Vineyards Ko-Op Ltd M & D Erf 312 Kuils River, Pinotage Str, WC 2008/02/20 N/A N/A Saxenburg Park, Kuils River RG 0012 Louis Trichardt Beer Wholesalers (Pty) Louis Trichardt Beer Wholesalers D Erf 05-04260, Byles Street, Industrial Area, LMP 2005/06/05 N/A N/A Ltd Louis Trichardt, Western Cape RG 0013 The South African Breweries Limited Sab ( Newlands) M & D 3 Main Road, Newlands WC 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0014 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Rustenburg) D Erf 1833, Cnr Ridder & Bosch Str, NW 2007/10/19 02/03/2011 Rustenburg RG 0015 Madadeni Beer Wholesalers (Pty) Ltd Madadeni Beer Wholesalers (Pty) D Lot 4751 Section 7, Madadeni, Newcastle, KZN -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

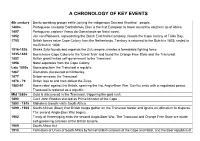

A Chronology of Key Events

A CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS 4th century Bantu speaking groups settle, joining the indigenous San and Khoikhoi people. 1480s Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias is the first European to travel round the southern tip of Africa. 1497 Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama lands on Natal coast. 1652 Jan van Riebeeck, representing the Dutch East India Company, founds the Cape Colony at Table Bay. 1795 British forces seize Cape Colony from the Netherlands. Territory is returned to the Dutch in 1803; ceded to the British in 1806. 1816-1826 Shaka Zulu founds and expands the Zulu empire, creates a formidable fighting force. 1835-1840 Boers leave Cape Colony in the 'Great Trek' and found the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. 1852 British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal. 1856 Natal separates from the Cape Colony. Late 1850s Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic. 1867 Diamonds discovered at Kimberley. 1877 Britain annexes the Transvaal. 1878 - 79 British lose to and then defeat the Zulus 1880-81 Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic. Mid 1880s Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. 1890 Cecil John Rhodes elected as Prime Minister of the Cape 1893 - 1915 Mahatma Gandhi visits South Africa 1899 - 1902 South African (Boer) War British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins. 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire.