National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Newsletter 2014-15 April 11, 2014 GOVERNOR CALLS SPECIAL

Newsletter 2014-15 April 11, 2014 GOVERNOR CALLS SPECIAL SESSION TO ADDRESS WAGE BILL, BUDGET ISSUES Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin says he plans to call a special session of the Legislature to correct problems with the minimum wage bill and to address issues with the 2015 fiscal year budget. The session is expected to be in conjunction with the May legislative interim meetings. H.B. 4283, which increases the state’s minimum wage incrementally, from $7.25 per hour to $8 per hour on January 1, 2015 and to $8.75 on January 1, 2016, contained an unintended consequence. As it is currently drafted, the bill prevents West Virginia employers from relying on certain existing overtime exemptions under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The business community, municipal and county governments, higher education institutions and others stated that previously exempt workers will become subject to overtime and maximum hours provisions. Cities and counties alone stated their fire and police budgets would increase hundreds of thousands of dollars. They recommended the governor veto the bill to eliminate the overtime language. Joining Gov. Tomblin in the bill’s signing were Senate President Jeff Kessler and House Speaker Tim Miley. They all pledged to preserve the federal exemptions and overtime provisions when the bill is brought up during the special session. State revenues continue to lag behind estimates. With one quarter left in this fiscal year, the state has a $78 million shortfall in revenues. While personal income tax collections are up, sales taxes are falling behind. (See this week’s Highway Bulletin for State Road Fund revenues). -

Description of the Monterey Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE MONTEREY QUADRANGLE. GEOGRAPHY. York to Alabama, and the lowlands of Tennessee, ing the lesser valleys along the outcrops of the Fork of Cheat River, which has considerable vol Kentucky, and Ohio. Its northwestern boundary softer rocks. These longitudinal streams empty ume at an altitude of 4000 feet and flows north | General relations. The Monterey quadrangle is indefinite, but may be regarded as into a number of larger, transverse rivers, which with moderate declivity, out of the northwestern | embraces the quarter of a square degree which an arbitrary line coinciding with the cross one or the other of the barriers limiting the corner of the quadrangle. I division. lies between parallels. 38° and 38° 30' north lati mlennessee V».Kiver from» northeasti '-*/Mis - valley. In the northern portion of the province The principal mountain ranges of the Monterey j tude and meridians 79° 30' and 80°. It measures sissippi to its mouth, and then crossing the States they form the Delaware, Susquehanna, Potomac, quadrangle are Warm Spring Mountain, Jack | approximately 34.5 miles from north to south and of Indiana and Ohio to western New York. Its James, and Roanoke rivers, each of which passes Mountain, Back Creek Mountain, Little 27.3 miles from east to west, and its area is about eastern boundary is defined by the Allegheny through the Appalachian Mountains in a narrow Mountain, Allegheny Mountain, and 942 square miles. In Virginia it comprises the Front and the Cumberland escarpment. The gap and flows eastward to the sea. In the cen Back Allegheny Mountains. In the greater part of Bath County and the Locationof rocks of this division are almost entirely of sedi tral portion of the province, in Kentucky and southeastern corner of the quadrangle are Chest western portion of Highland County. -

JACKSONKELLY„,C

JACKSONKELLY„,c 500 LEE STREET EAST • SUITE 1600 • P.O. BOX 553 • CHARLESTON. WEST VIRGINIA 25322 • TELEPHONE: 304-340-1000 • TELECOPIER: 304-340-1 1 30. www.jacksonketly.com E-mail Address: [email protected] Writer's Fax No.: 304-340-1272 Direct Dial No.: 304-340-1203 May 21, 2018 VIA ELECTRONIC AND U.S. MAIL Jackie D. Shultz Clerk of the Board Environmental Quality Board 601 57th Street, SE Charleston, WV 25304 Re: Susan Taylor Dropp. et al. v. WVDEP, Appeal No. 18-01-EQB Dear Ms. Shultz: On behalf of Mountaineer Gas Company and the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, enclosed for filing are the original and six (6)) copies of a JOINT MOTION TO DISMISS OR FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT ON CERTAIN CLAIMS OF APPELLANTS in the above-referenced appeal. Sincerely yours, eft-- A/4 CHRISTOPHER M. HUNTER CMH/sbo Enclosure cc: Susanne E. Thompson, w/enc. Rose Monahan, w/enc. Jason Wandling, w/enc. Bridgeport,VVV • Charleston,WV • Martinsburg,VVV • Morgantovm,VVV •Wheeling,WV 4850-8538-3782.v1 Denver, CO • Crawfordsville, IN • Evansville. IN • Lexington, KY •Akron, OH • Pittsburgh, PA •Washington, DC WEST VIRGINIA ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY BOARD CHARLESTON,WEST VIRGINIA SUSAN TAYLOR DROPP and LAURA STEEPLETON, Appellants, v. Appeal No. 18-01-EQB DIRECTOR,DIVISION OF WATER AND WASTE MANAGEMENT,DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION, Appellee, and MOUNTAINEER GAS COMPANY, Proposed Intervenor/Appellee. JOINT MOTION TO DISMISS OR FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT ON CERTAIN CLAIMS OF APPELLANTS I. INTRODUCTION By letter of February 7, 2018, Mountaineer Gas Company ("Mountaineer') obtained approval from the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection("WVDEP") to use a general water pollution control permit for discharges of stormwater associated with Mountaineer's "Eastern Panhandle Expansion Project" ("Project'). -

Appendix 1 – Watershed Tracking

Appendix 1 – Watershed tracking Plan Name Watershed Sub Watershed Sub BMP/Action Unit Goal Implemented TMLD LRs % Pollutant ID Unit LR Watershed Implemented Achieved Deckers Deckers WV Deckers WV M-8 Aggregated BMP Load Reductions Creek Creek Main Deckers Deckers WV Deckers WV M-8 Passive Treatment 1.00 Creek Creek Main Deckers Deckers WV Deep WV M-8-A.7 Passive Treatment 1.00 Creek Creek Hollow Deckers Deckers WV Dilan Creek WV M-8-G Passive Treatment 1.00 Creek Creek Deckers Deckers WV Hartman WV M-8- Passive Treatment 2.00 Creek Creek Run O.5A Deckers Deckers WV Kanes WV M-8-I Aggregated BMP Load Reductions 9,350.00 Metals 52,929.00 Creek Creek Creek (Aluminum) Deckers Deckers WV Kanes WV M-8-I Aggregated BMP Load Reductions 45,471.00 Metals (Iron) 72,119.00 Creek Creek Creek Deckers Deckers WV Kanes WV M-8-I Aggregated BMP Load Reductions Acidity LBS/YR 135,800.00 Creek Creek Creek Deckers Deckers WV Kanes WV M-8-I Constructed Wetland Aerobic INDIVIDUAL 3.00 3.00 100 Creek Creek Creek UNITS Deckers Deckers WV Kanes WV M-8-I Land Reconstruction, Abandoned UNITS 1.00 1.00 100 Creek Creek Creek Mined Land Deckers Deckers WV Kanes WV M-8-I Limestone Doser UNITS 2.00 2.00 100 Creek Creek Creek Deckers Deckers WV Kanes WV M-8-I Limestone Open Channel UNITS 4.00 4.00 100 Creek Creek Creek Deckers Deckers WV Kanes WV M-8-I Sulfate Reducing Bioreactor UNITS 1.00 1.00 100 Creek Creek Creek Deckers Deckers WV Laurel Run WV M-8-H Passive Treatment 1.00 Creek Creek Deckers Deckers WV Slab Camp WV M-8-F Aggregated BMP Load Reductions 4,974.00 Metals -

Morgan County Comprehensive Plan Advisory Committee

MORGAN COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PAGE PURPOSE OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN INT-1 ROLE OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN INT-4 MORGAN COUNTY DESCRIPTION INT-5 HISTORY OF MORGAN COUNTY INT-5 HISTORIC POPULATION INT-6 COMPREHENSIVE POLICIES INT-7 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES INT-9 IMPLEMENTING THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN INT-11 FUNDING OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN INT-12 CHAPTER 1 – LAND USE INTRODUCTION LU-1 EXISTING LAND USE LU-1 LAND USE ZONING REGULATIONS LU-4 POPULATION TRENDS LU-5 BUILDING INTENSITY LU-7 POPULATION PROJECTIONS LU-9 FACTORS AFFECTING GROWTH LU-11 LAND USE PLANNING TOOLS LU-12 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES LU-13 CHAPTER 2 – POPULATION AND HOUSING INTRODUCTION PH-1 DEMOGRAPHICS PH-1 POPULATION PH-3 HOUSING PH-6 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES PH-11 CHAPTER 3 – TRANSPORTATION INTRODUCTION TR-1 ROADS TR-1 BRIDGES TR-4 OTHER ROAD DEFICIENCIES TR-4 MAJOR IMPROVEMENTS TR-5 REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITIES TR-7 SCENIC BYWAYS TR-8 HIKING AND BIKING TRAILS TR-9 RAILROADS TR-10 AIR FACILITIES TR-11 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION TR-11 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES TR-12 CHAPTER 4 – PUBLIC UTILITIES & INFRASTRUCTURE INTRODUCTION INF-1 WATER INF-1 SEWER INF-4 WATER AND SEWER PLAN LIMITATIONS INF-6 CHESAPEAKE BAY INITIATIVE INF-10 SOLID WASTE INF-12 MISCELLANEOUS UTILITIES INF-14 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES INF-14 CHAPTER 5 – PUBLIC SERVICES INTRODUCTION PS-1 EDUCATIONAL FACILITIES PS-1 LIBRARIES PS-5 POLICE PS-6 FIRE AND EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICE PS-7 MEDICAL SERVICES PS-9 HISTORIC AND CULTURAL PS-11 LOCAL GOVERNMENT PS-12 ANIMAL CONTROL PS-13 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES -

RIVER BASIS BULLETIN 3 William A

RIVER BASIS BULLETIN 3 WATER RESOURCES OF THE POTOMAC RIVER BASIN, WEST VIRCXHIA0 William A* Bobbav Jr. 9 Eugene A. Friel; and Jaaea L. holm United States Geological Survey Prepared by the United States Geological Survey in cooperation with the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey and the West Virginia Department of natural Resources Division of Water Resources 1972 ~+ 4 CONTENTS PACK Summary ............................ 1 Introduction ......'................... 7 Purpose and scope . » ........... 11 Water resources ........................ 12 the hydrologic cycle ................... 18 Interrelationships between ground water and surface water 26 * * Gaining and losing streams «......*.*... 32 Streamflow separation ................. 37 Base flow ...................... 42 Surface water ...*...................... 49 Source ........................... 49 average Streamflow ................... 50 Low-flow magnitude and frequency ............. 59 Average 7-day low flow ............... 65 Flood magnitude and frequency ........ «. 68 High-flow frequency ................. 72 Water-supply storage requirements ............ 75 Flow duration ...................... 80 Effects of impoundments on flow duration ...... 85 Time of travel .....*................. 88 Ground water .*.....<, ................ 100 Source .......................... 100 Hydrology ........................ 101 High-relief areas of the Valley and Ridge province 102 ' ... ,; i CONTENTS ; ' Ground water - Continuad ; Hydrology - Continuad High-relief araaa of the Valley and -

Remembering Carla Hardy

West Virginia's Chesapeake Bay Update WV Chesapeake Bay Program Website Summer 2016, Issue 23 Quick Links Rememberiing Carlla Hardy West Virginia Chesapeake Bay Program U.S. EPA's Chesapeake Bay TMDL website What's My Watershed? "What's Your BMP?" Residential Stormwater BMP Reporting Tool In Thiis Issue Carla Hardy passed away unexpectedly on July 13, 2016. As Meet Karen Cladas the Chesapeake Bay Program Manager with the West Virginia Conservation Agency, she was an integral member of West Paddle the Potomac River Virginia's Chesapeake Bay Tributary Team. Carla edited this quarterly newsletter, initiated and carried out countless TMDL public meetings successful environmental projects and workshops, mentored and inspired others, and brought a lot of positive energy to Plant a Tree in Memory of Carla our work and our lives. We miss her! Hardy The diverse events and projects highlighted in this newsletter Rain Garden Volunteer are a testament to the partnerships that Carla fostered. Opportunity Because Carla was a visionary founder of the West Virginia CommuniTree Program, Cacapon Institute has renamed that Chesapeake Watershed Forum program after her, and has also organized a memorial tree planting program (application below) in her honor. The Watershed Celebration Day deadline to apply for this special opportunity is September 14. Applicants may request 1, 2, or 3 trees to plant on public or Save the Dates! private property. Stream Scholars Summer Camp Application for memorial trees Carla Hardy's obituary Eastern Panhandle Conservation -

TMDL) Development Process

West Virginia Draft 2016 Section 303(d) List Listing Rationale Table of Contents Overview .................................................................................................................................................. 2 303(d) Listing Process .............................................................................................................................. 2 West Virginia Water Quality Standards .................................................................................................... 2 Data Management .................................................................................................................................... 4 Assessed Data .............................................................................................................................. 4 Use Assessment Procedures (303(d) Listing Methodology) ................................................................... 4 Numeric water quality criteria .................................................................................................... 4 Segmentation of streams and lakes .............................................................................................. 6 Evaluation of fecal coliform numeric criteria ............................................................................. 6 Narrative water quality criteria – biological impairment data ................................................... 7 Narrative water quality criteria – fi sh consumption advisories ................................................. -

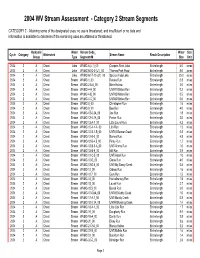

2004 WV Stream Assessment - Category 2 Stream Segments

2004 WV Stream Assessment - Category 2 Stream Segments CATEGORY 2 - Attaining some of the designated uses; no use is threatened; and insufficient or no data and information is available to determine if the remaining uses are attained or threatened. Hydryolic Water Stream Code_ Water Size Cycle Category Watershed Stream Name Reach Description Group Type Segment ## Size Unit 2004 2 A Cheat Lake WVMC-6-(L1)_00 Coopers Rock Lake Entire length 6.0 acres 2004 2 A Cheat Lake WVMC-60-D-3-(L1)_00 Thomas Park Pond Entire length 8.0 acres 2004 2 A Cheat Lake WVMC-60-T-10-(L1)_00 Spruce Knob Lake Entire length 25.0 acres 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-1_00 Rubles Run Entire length 0.8 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-2.5-A_00 Birch Hollow Entire length 2.0 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-4-A_00 UNT#1/Whites Run Entire length 0.2 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-4-B_00 UNT#2/Whites Run Entire length 0.5 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-4-C_00 UNT#3/Whites Run Entire length 0.6 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-8_00 Christopher Run Entire length 1.6 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-9_00 Bee Run Entire length 4.0 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-12-0.3A_00 Joe Run Entire length 1.8 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-12-0.7A_00 Parker Run Entire length 2.0 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-12-A-1_00 Little Laurel Run Entire length 4.2 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-12-A-1-A_00 Lick Run Entire length 1.5 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-12-B-1-B_00 UNT#1/Beaver Creek Entire length 0.8 miles 2004 2 A Cheat Stream WVMC-12-B-2_00 Barnes Run Entire length 4.8 -

Etteer of Virginia

Bulletin No. 232 . Series F, Geography, 40 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIKKCTOR A ETTEER OF VIRGINIA BY HENRY WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 O LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Washington, ]). 0., March 9, 190Jh SIR: I have the honor to transmit herewith, for publication as a bulletin, a gazetteer of Virginia. Very respectful!}7 , HENRY GANNETT, Geographer. Hon. CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Director United States Geological Survey. A GAZETTEER OF VIRGINIA. By HENKY GANNETT. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE STATE. Virginia is one of tho easternmost States of the Union. It lies on the Atlantic seaboard between latitudes 36° 30' and 39° 30' and longi tudes 75° and 84°. Its limits are very irregular, except on the south, and even there the boundary, though nominally a parallel of latitude, is actually by no means such a line. From the Atlantic Ocean, just above the parallel of 38°, the bound ary crosses the peninsula known as the Eastern Shore, which separates Chesapeake Bay from the Atlantic, in a direction south of west. Then, after a sinuous course among islands fringing the west coast of this peninsula, it crosses Chesapeake Bay to a point on the south side of the mouth of Potomac River. It follows the south bank of the Potomac at low-water line up to Harpers Ferry, where the river cuts through the Blue Ridge. Here the boundary leaves the river and makes a generally southwest course, with several jogs to the northwest, to a point near the head of the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy. -

4 South Branch Potomac 5 Upper Kanawha 6 Upper Ohio North 7

1 Cheat River 2 Shenandoah (Jefferson) 3 Shenandoah (Hardy) Group A Group B Group C Group D Group E 4 South Branch Potomac 5 Upper Kanawha 6 Upper Ohio North 7 Youghiogheny 8 Coal 9Elk 10 Lower Kanawha 11 North Branch Potomac 12 Tygard Valley 13 Gauley 14 Lower Guyandotte 15 Middle Ohio North 16 Middle Ohio South 17 Potomac Direct Drains 18 Tug Fork 19 Greenbrier 20 James 21 Little Kanawha 22 Lower New 23 Monongahela 24 Upper New 25 Big Sandy 26 Cacapon 27 Dunkard 28 Lower Ohio 29 Twelvepole 30 Upper Guyandotte 31 Upper Ohio South 32 West Fork DEP NAME HUC8 NAME HUC8 HUC12 NAME HUC12 STATES SQ MILES ACRES South Branch Potomac South Branch Potomac 02070001 Laurel Fork-North Fork South Branch Potomac River 020700010101 VA,WV 163800592.52 40475.85 South Branch Potomac South Branch Potomac 02070001 Big Run 020700010102 WV 75626357.11 18687.61 South Branch Potomac South Branch Potomac 02070001 Red Lick Run-North Fork South Branch Potomac River 020700010103 WV 83347492.84 20595.53 South Branch Potomac South Branch Potomac 02070001 Headwaters Seneca Creek 020700010104 WV 101242748.20 25017.53 South Branch Potomac South Branch Potomac 02070001 Outlet Seneca Creek 020700010105 WV 75159367.82 18572.21 South Branch Potomac South Branch Potomac 02070001 Mill Creek-North Fork South Branch Potomac River 020700010106 WV 116738766.84 28846.66 South Branch Potomac South Branch Potomac 02070001 Zeke Run-North Fork South Branch Potomac River 020700010107 WV 83601026.60 20658.18 South Branch Potomac South Branch Potomac 02070001 Jordan Run-North Fork South