Report of Thomas Moore's 1820 Potomac River Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix M: Aquatic Biota Monitoring Table

NATURAL RESOURCES TECHNICAL REPORT APPENDIX M: AQUATIC BIOTA MONITORING TABLE Final – May 2020 Aquatic Habitat, BIBI, and FIBI Scores and Rankings for Monitoring Sites within the Vicinity of the I-495 & I-270 Managed Lanes Study Corridor Aquatic Habitat BIBI FIBI MDE 12-digit Watershed Site Waterway Source Site I.D. Year Narrative Narrative Narrative Name Coordinates Method Score Score Score Ranking Ranking Ranking Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2008 -- -- -- 19.1 Very Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2009 -- -- -- 15.5 Very Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2010 -- -- -- 30.5 Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2011 -- -- -- 29.7 Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2012 -- -- -- 13.3 Very Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2013 -- -- -- 12.5 Very Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2014 -- -- -- 38 Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2015 -- -- -- 27.7 Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 Dead Run FCDPWES -77.176163 1646305 2016 -- -- -- 27.4 Poor -- -- Fairfax County Middle 38.959552, Potomac Watersheds1 -

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

02070001 South Branch Potomac 01605500 South Branch Potomac River at Franklin, WV 01606000 N F South Br Potomac R at Cabins, WV 01606500 So

Appendix D Active Stream Flow Gauging Stations In West Virginia Active Stream Flow Gauging Stations In West Virginia 02070001 South Branch Potomac 01605500 South Branch Potomac River At Franklin, WV 01606000 N F South Br Potomac R At Cabins, WV 01606500 So. Branch Potomac River Nr Petersburg, WV 01606900 South Mill Creek Near Mozer, WV 01607300 Brushy Fork Near Sugar Grove, WV 01607500 So Fk So Br Potomac R At Brandywine, WV 01608000 So Fk South Branch Potomac R Nr Moorefield, WV 01608070 South Branch Potomac River Near Moorefield, WV 01608500 South Branch Potomac River Near Springfield, WV 02070002 North Branch Potomac 01595200 Stony River Near Mount Storm,WV 01595800 North Branch Potomac River At Barnum, WV 01598500 North Branch Potomac River At Luke, Md 01600000 North Branch Potomac River At Pinto, Md 01604500 Patterson Creek Near Headsville, WV 01605002 Painter Run Near Fort Ashby, WV 02070003 Cacapon-Town 01610400 Waites Run Near Wardensville, WV 01611500 Cacapon River Near Great Cacapon, WV 02070004 Conococheague-Opequon 01613020 Unnamed Trib To Warm Spr Run Nr Berkeley Spr, WV 01614000 Back Creek Near Jones Springs, WV 01616500 Opequon Creek Near Martinsburg, WV 02070007 Shenandoah 01636500 Shenandoah River At Millville, WV 05020001 Tygart Valley 03050000 Tygart Valley River Near Dailey, WV 03050500 Tygart Valley River Near Elkins, WV 03051000 Tygart Valley River At Belington, WV 03052000 Middle Fork River At Audra, WV 03052450 Buckhannon R At Buckhannon, WV 03052500 Sand Run Near Buckhannon, WV 03053500 Buckhannon River At Hall, WV 03054500 Tygart Valley River At Philippi, WV Page D 1 of D 5 Active Stream Flow Gauging Stations In West Virginia 03055500 Tygart Lake Nr Grafton, WV 03056000 Tygart Valley R At Tygart Dam Nr Grafton, WV 03056250 Three Fork Creek Nr Grafton, WV 03057000 Tygart Valley River At Colfax, WV 05020002 West Fork 03057300 West Fork River At Walkersville, WV 03057900 Stonewall Jackson Lake Near Weston, WV 03058000 West Fork R Bl Stonewall Jackson Dam Nr Weston 03058020 West Fork River At Weston, WV 03058500 W.F. -

Part 2 Markings Colonial -1865, Which, While Not Comprehen- Sive, Has the Advantage of Including Postal Markings As by Len Mcmaster Well As Early Postmasters6

38 Whole Number 242 Hampshire County West Virginia Post Offices Part 2 Markings Colonial -1865, which, while not comprehen- sive, has the advantage of including postal markings as By Len McMaster well as early postmasters6. Previously I discussed a little of the history of Hamp- Thus I have attempted to identify the approximate shire County, described the source of the data and the location and dates of operation of the post offices es- conventions used in the listings, and began the listing of tablished in Hampshire County, explaining, where pos- the post offices from Augusta through Green Valley sible, the discrepancies or possible confusion that ex- Depot. The introduction is repeated here. ists in the other listings. Because of the length of the material, it has been broken up into three parts. This Introduction part will include the balance of the Hampshire county Several people have previously cataloged the Hamp- post office descriptions starting with Hainesville, and shire County West Virginia post offices, generally as the third part will include descriptions of the post of- part of a larger effort to list all the post offices of West fices in Mineral County today that were established in Virginia. Examples include Helbock’s United States Post Hampshire County before Mineral County was split off, Offices1 and Small’s The Post Offices of West Vir- and tables of all the post offices established in Hamp- ginia, 1792-19772. Confusing this study is that Hamp- shire County. shire County was initially split off from Virginia with Individual Post Office Location the establishment of many early post offices appearing in studies of Virginia post offices such as Abelson’s and History of Name Changes 3 Virginia Postmasters and Post Offices, 1789-1832 Hainesville (Haines Store) and Hall’s “Virginia Post Offices, 1798-1859”4; and that Hampshire County was itself eventually split into all or Hainesville was located near the crossroads of Old parts of five West Virginia counties, including its present Martinsburg Road (County Route 45/9) and Kedron day boundaries. -

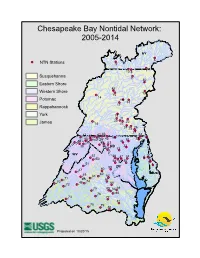

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014 NY 6 NTN Stations 9 7 10 8 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 Western Shore 12 15 14 Potomac 16 13 17 Rappahannock York 19 21 20 23 James 18 22 24 25 26 27 41 43 84 37 86 5 55 29 85 40 42 45 30 28 36 39 44 53 31 38 46 MD 32 54 33 WV 52 56 87 34 4 3 50 2 58 57 35 51 1 59 DC 47 60 62 DE 49 61 63 71 VA 67 70 48 74 68 72 75 65 64 69 76 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: All Stations NTN Stations 91 NY 6 NTN New Stations 9 10 8 7 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 12 Western Shore 92 15 16 Potomac 14 PA 13 Rappahannock 17 93 19 95 96 York 94 23 20 97 James 18 98 100 21 27 22 26 101 107 24 25 102 108 84 86 42 43 45 55 99 85 30 103 28 5 37 109 57 31 39 40 111 29 90 36 53 38 41 105 32 44 54 104 MD 106 WV 110 52 112 56 33 87 3 50 46 115 89 34 DC 4 51 2 59 58 114 47 60 35 1 DE 49 61 62 63 88 71 74 48 67 68 70 72 117 75 VA 64 69 116 76 65 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Table 1. -

The Future Belongs to Those Who Believe in the Beauty of Their Dreams. –Eleanor Roosevelt ALMA MATER

143RD May 11 - 13, 2012 The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams. –Eleanor Roosevelt ALMA MATER Alma, our Alma Mater, The home of Mountaineers. Sing we of thy honor, Everlasting through the years. Alma, our Alma Mater, We pledge in song to you. Hail, all hail, our Alma Mater, West Virginia “U.” —Louis Corson COMMENCEMENT 2012 | 1 Dear Graduates: Congratulations! You have worked hard to reach this day – the day you become a graduate of West Virginia University. Your hard work, perseverance, and enthusiasm for learning helped to get you to this point. With these qualities and the knowledge and skills acquired at WVU, you can achieve great things. To families and friends who are with us today to celebrate – thank you! You have played a critical role in helping students succeed in college, and you share credit for helping our students reach this monumental point in their lives. Graduates, you now belong to our worldwide alumni family of 180,000. Please stay in touch with us, and wear your flying WV with pride wherever your dreams may take you. Please visit us often. You always have a home here at WVU – where we are united in Mountaineer spirit. Best wishes for continued success. We are proud to call you one of our own. Let’s Go Mountaineers! Sincerely, James P. Clements, Ph.D. President West Virginia University COMMENCEMENT 2012 | 2 COMMENCEMENT 2012 | 3 Dear Graduates: Graduation is always a special celebration among Mountaineers! Today, you join more than 180,000 graduates who proudly represent their alma mater all over the world. -

Maryland's 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards

Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards EPA Approval Date: July 11, 2018 Table of Contents Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards ............................................ 3 Nationally Recommended Water Quality Criteria Considered with Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Re-evaluation of Maryland’s Restoration Variances ...................................................................... 5 Other Future Water Quality Standards Work ................................................................................. 6 Water Quality Standards Amendments ........................................................................................... 8 Designated Uses ........................................................................................................................... 8 Criteria ....................................................................................................................................... 19 Antidegradation.......................................................................................................................... 24 2 Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards The Clean Water Act (CWA) requires that States review their water quality standards every three years (Triennial Review) and revise the standards as necessary. A water quality standard consists of three separate but related -

Potomac River Water Quality and Habitat Assessment Overall Condition 2012-2014

Larry Hogan, Governor Boyd Rutherford, Lt. Governor Mark Belton, Secretary Tidewater Ecosystem Assessment Joanne Throwe, Deputy Secretary Potomac River Water Quality and Habitat Assessment Overall Condition 2012-2014 The Potomac River watershed includes area in Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Washington D.C. For the purpose of this report, the basin is divided into four regions: the Upper Potomac, Shenandoah, Middle Potomac and Lower Potomac (Figure 1). Land use in the upper Potomac River watershed was estimated to be 69% forest and 22% agriculture (Figure 1, Table 1).1 The Upper Potomac watershed is largely within West Virginia (54%), with other portions in Pennsylvania (22%), Maryland (18%) and Virginia (7%). Impervious surfaces cover 1% of the Maryland potion of the Upper river basin (Table 1).2 Land use in the Shenandoah watershed was estimated to be 56% forest and 34% agriculture. The Shenandoah watershed is almost entirely in Virginia (96%), with a small area in West Virginia (4%). Land use in the Middle Potomac watershed was estimated to be 44% agriculture, 32% forest and 20% developed. The Middle Potomac watershed includes areas in Maryland (55%), Virginia (34%), Pennsylvania (13%) and Washington D.C. (0.1%). Impervious surfaces cover 7% of the Maryland potion of the Middle river basin. Land use in the Lower Potomac watershed was estimated to be 41% forest, 30% developed, and 16% agriculture. The Lower Potomac watershed includes Figure 1 Potomac River basin Top panel shows state boundaries and the individual watersheds. Bottom panel shows the land use throughout the basin for 2011.1 Potomac River Water Quality and Habitat Assessment Overall Condition 2012-2014 1 areas in Virginia (56%), Maryland (42%) and Washington D.C. -

Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You!

American Council of Engineering Companies of Metropolitan Washington Water & Wastewater Business Opportunities Networking Luncheon Presented by Matthew Doyle, Branch Chief, Wastewater Design and Construction Division Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You! A Fairfax County, VA, publication August 20, 2019 Introduction • Matt Doyle, PE, CCM • Working as a Civil Engineer at Fairfax County, DPWES • BSCE West Virginia University • MSCE Johns Hopkins University • 25 years in the industry (Mid‐Atlantic Only) • Adjunct Hydraulics Professor at GMU • Director GMU‐EFID (Student Organization) Presentation Objectives • Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Infrastructure • Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Organization (Staff) • Snapshot of our Current Projects • New Opportunities To work with DPWES • Use of Technologies and Trends • Helpful Hyperlinks Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Infrastructure • Wastewater Collection System • 3,400 Miles of Sanitary Sewer (Average Age 60 years old) • 61 Pumping Stations (flow ranges are from 25 GPM to 25 MGD) • 90 Flow Meters (Mostly billing meters) • 135 Grinder pumps • Wastewater Treatment Plant • 1 Wastewater Treatment Plant • Noman M. Cole Pollution Control Plant, Lorton • 67 MGD • Laboratory • Reclaimed Water Reuse System • 6.6 MGD • 2 Pump Stations • 0.750 MG Storage Tank • Level 1 Compliance • Convanta, Golf Course and Ball Fields Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Organization • Wastewater Management Program (Three Areas) – Planning & Monitoring: • Financial, -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Planning Assistance to States Jennings Randolph Lake Scoping Study Phase II Report

~ ~ U. S. Army Corps Interstate Commission of Engineers on the Potomac River Basin Planning Assistance to States Jennings Randolph Lake Scoping Study Phase II Report APRIL 2020 Prepared by: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District Laura Felter and Julia Fritz and Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin Cherie Schultz, Claire Buchanan, and Gordon Michael Selckmann Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Study Authority ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Congressional Authorizations and Project Objectives .................................................................. 3 1.4 Study Area Management .............................................................................................................. 4 2 Scoping Studies ..................................................................................................................................... 7 3 Watershed Conditions Analysis ........................................................................................................... -

Capper-Cramton Resource Guide 2019

Resource Guide Review of Projects on Lands Acquired Under the Capper-Cramton Act TAME Coalition TAME F A Martin Northwest Branch Trail Indian Creek Stream Valley Park Overview The Capper-Cramton Act (CCA) of 1930 (46 Stat. 482) was enacted for the acquisition, establishment, and development of the George Washington Memorial Parkway and stream valley parks in Maryland and Virginia to create a comprehensive park, parkway, and playground system in the National Capital.1 In addition to authorizing funding for acquisition, the act granted the National Capital Park and Planning Commission, now the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), review authority to approve any Capper-Cramton park development or management plan in order to ensure the protection and preservation of the region’s valuable watersheds and parklands. Subsequent amendments to the Capper-Cramton Act2 allocated funds for the acquisition and extension of this park and parkway system in Maryland and Virginia. Title to lands acquired with such funds or lands donated to the United States as Capper Cramton land is vested in the state in which it is located. The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (M-NCPPC) utilized Capper-Cramton funds to protect stream valleys in parts of Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties. Similarly, the District of Columbia used federal funds to develop recreation centers, playgrounds, and park systems. There is no evidence that Virginia utilized Capper-Cramton funds to acquire stream valley parks under the CCA. Today, over 10,000 acres of Capper-Cramton land have been established and preserved as a result of the act. This resource guide is for general information purposes, and is not a regulatory document.