Light at Night Reduces Digestive Efficiency of Developing Birds: an Experiment with King Quail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes)

Galliform Baraminology 1 Running Head: GALLIFORM BARAMINOLOGY A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes) Michelle McConnachie A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2007 Galliform Baraminology 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Timothy R. Brophy, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Marcus R. Ross, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Harvey D. Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Judy R. Sandlin, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Program Director ______________________________ Date Galliform Baraminology 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, without Whom I would not have had the opportunity of being at this institution or producing this thesis. I would also like to thank my entire committee including Dr. Timothy Brophy, Dr. Marcus Ross, Dr. Harvey Hartman, and Dr. Judy Sandlin. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brophy who patiently guided me through the entire research and writing process and put in many hours working with me on this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their interest in this project and Robby Mullis for his constant encouragement. Galliform Baraminology 4 Abstract This study investigates the number of galliform bird holobaramins. Criteria used to determine the members of any given holobaramin included a biblical word analysis, statistical baraminology, and hybridization. The biblical search yielded limited biosystematic information; however, since it is a necessary and useful part of baraminology research it is both included and discussed. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Peacock-Pheasants (Galliformes: Polyplectron Spp.) Indicates Loss and Reduction of Ornamental Traits and Display Behaviours

Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (2001), 73: 187–198. With 3 figures doi:10.1006/bijl.2001.0536, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on A molecular phylogeny of the peacock-pheasants (Galliformes: Polyplectron spp.) indicates loss and reduction of ornamental traits and display behaviours REBECCA T. KIMBALL1,2∗, EDWARD L. BRAUN1,3, J. DAVID LIGON1, VITTORIO LUCCHINI4 and ETTORE RANDI4 1Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA 2Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 3Department of Plant Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 4Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca` Fornacetta 9, 40064 Ozzano dell’Emilia (BO), Italy Received 4 September 2000; accepted for publication 3 March 2001 The South-east Asian pheasant genus Polyplectron is comprised of six or seven species which are characterized by ocelli (ornamental eye-spots) in all but one species, though the sizes and distribution of ocelli vary among species. All Polyplectron species have lateral displays, but species with ocelli also display frontally to females, with feathers held erect and spread to clearly display the ocelli. The two least ornamented Polyplectron species, one of which completely lacks ocelli, have been considered the primitive members of the genus, implying that ocelli are derived. We examined this hypothesis phylogenetically using complete mitochondrial cytochrome b and control region sequences, as well as sequences from intron G in the nuclear ovomucoid gene, and found that the two least ornamented species are in fact the most recently evolved. Thus, the absence and reduction of ocelli and other ornamental traits in Polyplectronare recent losses. -

Section P, Quales and Partridges.Cdr

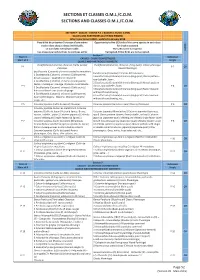

SECTIONS ET CLASSES O.M.J./C.O.M. SECTIONS AND CLASSES O.M.J./C.O.M. SECTION P - CAILLES - COLINS P.E. ( BAGUES 1 ET/OU 2 ANS) QUAILS AND PARTRIDGES (1/2 YEARS RINGED) Mise à jour Janvier 2018 - updated in January 2018 Possibilité de présenter 5 oiseaux d'une même Opportunity to five (5) birds of the same species in each class C A espèce dans chaque classe individuelle. for singles accepted GE Le nom lan est indispensable. The Lan name is required. S Les oiseaux panachés-frisés ne sont pas admis Variegated-frilled birds are not accepted. Secon P Stam 4 Individuel CAILLES - COLINS DOMESTIQUES Stam of 4 Single QUAILS AND PARTRIDGES DOMESTIC Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) Excalfactoria(coturnix) chinensis. (King quail) Classic phenoype P 1 P 2 O1 Classique Classic Phenotype Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis toutes les mutaons Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis All mutaons: 1 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 1 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Classic paern : Dessin sauvage : Opale,Brune etIsabelle . opal,Isabelle , fawn.. 2 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 2 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Mosaïc paern Facteur mosaïque : sauvage, Opale,Brune etIsabelle P 3 classic, opal,Isabelle , fawn. P 4 O1 3 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 3 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Factor melanic Patron mélanisé sans dessin de gorge without throat drawing 4 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 4 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis -

Comparison of Cytochrome B Region Among Chinese Painted Quail, Wild-Strain Quail, and White Broiler Chicken Based on PCR-RFLP Analysis

287 Comparison of Cytochrome b Region Among Chinese Painted Quail, Wild-Strain Quail, and White Broiler Chicken Based on PCR-RFLP Analysis Xiang-Jun SHEN1),Hidenori SUZUKI2)*, Masaoki TSUDZUKI3), Shin'ichiITO2) and Takao NAKAMURA2)** 1)The United Graduate School of AgriculturalScience , 2)Faculty of Agriculture, GifuUniversity, Gifu 501-1193 3)Faculty of AppliedBiological Science , Hiroshima University,Higashi-Hiroshima 739-8528 PCR-RFLPanalysis was used to examine 1,075 bp cytochromeb (Cyt b) region of mtDNAineach of 20birds of Chinese painted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis), wild-strain Japanesequail (Coturnix japonica), and white broiler chicken (Gallus gallus). The total Cytb ampliconwas digested with 10 restriction endonucleases, andits electrophoretic patternwas investigated. Ten kinds of restrictionenzyme digestions were identical among20 individuals ineach of the three species. No variation was observed in the 10 kindsof enzymedigestions among different individuals within the threespecies in- vestigated.The different specific electrophoretic patterns, haplotypes, and total restric- tionfragments were observed in eachof the three species belonging tothe same family Phasianidae.The result representatives the evolutionarygenetic characteristics of RFLPof cytochromeb region in thethree different species, and indicated the genetic diversityamong the three genuses of the family Phasianidae, and genetic identity within eachof thespecies. The result could be used for the identification of different species withinfamily Phasianidae and as a referenceofphysical map for cytochrome b gene. (Jpn.Poult. Sci., 36: 287-294, 1999) Keywords:PCR-RFLP, cytochrome b,Excalfactoria chinensis, Coturnix japonica, Gallus gallus Introduction Chinesepainted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) belongs to the orderGalliformes, family Phasianidae,and genus Excalfactoria,(YAMASHINA, 1986). Japanese quail belongsto the samefamily Phasianidae, a different genus Coturnix (CRAWFORD, 1990). -

Rapid Communication- Primer Design and Sequence Information for Cytochrome B Gene in the Chinese Painted Quail (Excalfactoria C

-Rapid Communication- Primer Design and Sequence Information for Cytochrome b Gene in the Chinese Painted Quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) Xiang-Jun SHEN, Masaoki TSUDZUKIa, Takao NAKAMURAb The United Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Gifu University, Gifu-shi 501-1193, Japan Faculty of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima-shi 739-8528,a Japan bFaculty of Agriculture , Gifu University, Gifu-shi 501-1193, Japan (Received April 21, 1999; Accepted May 15, 1999) Abstract In accordance with the chicken and quail mitochondrialDNA sequences,three pairs of primers encompassing light and heavy strand (L14832, L15269, L15500, H15924, H15497, and H16207) with high specificity were designed, synthesized, and used for amplification and sequencing of cytochrome b (Cyt b) gene. The PCR products were sequenced by the direct-sequencing method. The Chinese painted quail cytochrome b gene consisted of 1,143bp nucleotides (base composition: 327 A; 399 C; 281 T and 136 G), encoded for a 380 amino acid sequence, and showed 89.0%, 86.4%, and 86.2%, homology with nucleotide sequences of Japanese quail, silky fowl, and White Leghorn chicken, respectively. The homology of the amino acid sequence of the cytochrome b gene of Chinese painted quail showed 98.2%, 95.3%, and 95.3% with those of Japanese quail, silky fowl, and White Leghorn chicken, respectively. The sequencesreported in this paper have been depositedin the GenBank database(Accession No. AF109217). Animal Science Journal 70 (4): 240-242,1999 Key words: Chinese painted quail,Excalfactoria chinensis, Cytochromeb, Sequence,Homology Chinese painted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) belongs the test: to the order Galliformes, family Phasianidae, genus (1) L14832: 5'-TACCTGGGTTCCTTCGCCCT-3' Excalfactoria5),and it is the smallest species in the family (2) H15497: 5'-TGTAGGAAGGTGAGTGGAT-3' Phasianidae. -

Download Article (PDF)

PERNo. 330 i s (Aves)· t e Co ·0 0 t e rv yo dia • IVE • RVEYO ' OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 330 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Catalogue of Type Specilllens (Aves) in the National Zoological Collection of the Zoological Survey of India R. SAKTHIVE"L*, B.B. DUTrA & K. VENKATARAMAN** (*[email protected] & [email protected]; **[email protected]) Zoological Survey of India M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053 Zoological Survey of India Kolkata CITATION Sakthivel, R., Dutta, B.B. and Venkataraman, K. 2011. Catalogue of type specimens (Aves) in the National Zoological Collection of the Zoological Survey of India, Rec. zoc;>l. Surv. India, Occ. Paper No. 330 : 1-174 (Published by the Director, Zool. Surv. India, Kolkata) Published : November, 2011 ISBN 978-81-8171-294-3 © Gout. ofIndia, 2011 All RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stomp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE India : ~ 525.00 Foreign: $ 35; £ 25 Published at the Publication Division by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053 and printed at Calcutta Repro Graphics, Kolkata-700 006 CONTENTS INfRODUcrION ................................................................................................................. -

7 Social Behavior and Vocalizations

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences May 2008 7 Social Behavior and Vocalizations Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscigrouse Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "7 Social Behavior and Vocalizations" (2008). Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard. 9. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscigrouse/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Social Behavior and Vocalizations 0NE of the most complex and fascinating aspects of grouse and quail biology is their social behavior, particularly that related to reproduction. Natural selection in the quail group has seemingly favored the retention of a monogamous mating system with the associated advan- tages of maintaining the pair bond through the breeding season. This system allows the male to participate in the protection of the nest, possibly participate in incubation, and later care for the brood. It also provides the possibility, if not the frequent actuality, that the male might undertake the entire incubation or rearing of the first brood, while the female is freed to lay a second clutch and rear a second brood in a single breeding season. In addition, within the quails may be seen a breakdown of typical avian territorial behavior patterns, probably resulting from the greater survival value of ecological adaptations favoring sociality in these birds. -

Blue-Breasted Quail (Excalfactoria Chinensis)

Animal (2011), 5:10, pp 1506–1514 & The Animal Consortium 2011 animal doi:10.1017/S1751731111000589 Estimating the requirement of dietary crude protein for growing blue-breasted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) - H. W. Wei1, T. L. Hsieh1, S. K. Chang2, W. Z. Chiu1, Y. C. Huang1 and M. F. Lin1 1Department of Animal Science and Technology, National Taiwan University, No. 50, Lane 155, Section 3 Keelung Road, Taipei 106, Taiwan; 2School of Veterinary Medicine, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Sector 4 Roosevelt Road, Taipei 106, Taiwan (Received 11 August 2010; Accepted 15 March 2011; First published online 26 April 2011) Two experiments were conducted to investigate the requirement for dietary crude protein (CP) in growing blue-breasted quail (BBQ). In Experiment 1, 300 1-day-old quails were randomly assigned to 10 groups according to a 2 3 5 factorial arrangement of treatments with two metabolisable energy (ME) levels (12.13 and 13.39 MJ/kg) and five CP concentrations (160, 190, 220, 250 and 280 g/kg) for 8 weeks. In Experiment 2, 300 1-day-old quails were subjected to a different factorial arrangement of treatments with two ME levels (11.51 and 12.13 MJ/kg) and five CP concentrations (210, 220, 230, 240 and 250 g/kg) for 28 days. Experiment 1 revealed that an interaction existed in weight gain between ME and CP levels in weeks 1 to 4. In both ME groups, quails receiving CP of 160 g/kg showed the least weight gains (P , 0.05). No differences (P . 0.05) existed in weight gain between the ME groups in which quails ingested CP of 250 and 280 g/kg, whereas quails consuming CP of 220 g/kg with an ME of 13.39 MJ/kg had smaller weight gain than did those ingesting higher CP concentrations (P , 0.05). -

Excalfactoria and a Bird and Word Book to Keep You Warm Page 1 of 1

Book Review Excalfactoria and a bird and word book to keep you warm Page 1 of 1 Excalfactoria and a bird and word book to keep BOOK TITLE: you warm Latin for birdwatchers BOOK COVER: Chico, California, bordered by almond orchards and home to the US Yo-Yo Museum, seems an unlikely place to find an erudite husband-and-wife team who love birds, and words, and Latin. Roger Lederer and Carol Burr both have PhDs and both are Emeritus Professors at California State University, Chico – he of Biological Sciences and she of English. On his website, Lederer says he ‘knows exactly what birds you will find anywhere in the world’; he has travelled to over 100 countries. He has written five previous books on birds, and a 1984 textbook on Ecology and Field Biology. Burr is using her retirement from teaching English and Women’s Studies to paint and draw, in oils, water colours, pen and coloured pencils (the medium that she has used in illustrating Latin for Birdwatchers). Latin for Birdwatchers sets out to explore and explain 3000 scientific bird names, listed alphabetically. It does not claim to be comprehensive: there are about 20 000 bird names. Those scientific names are the Linnaean binomial names, that is, the paired names of genus and species in the system set up by Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) for naming everything alive. Although BirdLife South Africa works hard to promote the use of these names, birdwatchers tend to show less interest in Linnaean binomials than do, for example, tree watchers, but they are the only definitive names for birds (and trees). -

A SUPERTREE of BIRDS Katie E. Davis

REWEAVING THE TAPESTRY: A SUPERTREE OF BIRDS Katie E. Davis Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of Glasgow, Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, January 2008 © K. E. Davis 2008 Declaration I attest that: All material presented in this document was compiled and written by myself unless otherwise acknowledged. Part of the material included in this thesis is being prepared for submission in co-authorship with others: • Chapter 2: Davis, K. E. and Dyke, G. J. In Prep for Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie . “Two new specimens of Primobucco (Aves: Coraciiformes) from the Eocene of North America”. K. E. D. carried out the descriptive work, phylogenetic analyses and wrote the manuscript. G. J. D. provided the specimens and advised on description and writing of the manuscript. • Chapter 6: Lloyd, G. T., Davis, K. E., Pisani, D., Tarver, J. E., Ruta, M., Sakamoto, M., Hone, D. W. E., Jennings, J., Benton, M. J. In Prep for Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “Dinosaurs and the Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution”. KED and GTL designed the data collection protocols. GTL, JET, MS, DWEH and RJ performed data collection and entry. KED and DP created the MRP matrices. DP ran tree searches, performed post hoc taxon pruning and produced support values. MJB and GTL collected the stratigraphic data and GTL performed the subsampling tests and calculated diversification rates. JET, MR and GTL performed the time-slicing and diversification shift analyses. MJB, GTL, JET, DP, MR and KED wrote the paper. GTL and JET produced the Supporting Information and Figures. -

Energy and Protein Requirements During Various Stages of Production in Japanese Quails K

International Journal of Science, Environment ISSN 2278-3687 (O) and Technology, Vol. 8, No 4, 2019, 790 – 794 2277-663X (P) Review Article ENERGY AND PROTEIN REQUIREMENTS DURING VARIOUS STAGES OF PRODUCTION IN JAPANESE QUAILS K. Shibi Thomas, R. Amutha, M.R. Purushothaman, P.N. Richard Jagatheesan, S. Ezhilvalavan and V. Jayalalitha Veterinary University Training and Research Centre, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University (TANUVAS) 7/2, Kozhi Pannai Road, Kottapattu, Trichy – 620 023 Tamil Nadu E-mail: [email protected] Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) is a diversified domesticated poultry species reared for commercial egg and meat production. It is blessed with the unique characteristics of fast growth, early sexual maturity, high rate of egg production, short generation interval and shorter incubation period that makes it suitable for diversification. Other quail species include European quail (Coturnix coturnix), the bobwhite (Colinus virginianus), the California (Lophortyx californica), and the Chinese painted (Excalfactoria chinensis) (Ani et al., 2009). Japanese quail is also known by other names such as Common quail, Eastern quail, Asiatic quail, Stubble quail, Pharoah's quail, Red-throat quail, Japanese gray quail, Japanese migratory quail, King quail and Japanese King quail (NRC, 1991). Japanese quail are raised mainly for meat and egg production and also are valued research animals (NRC, 1994). Japanese quails have less feeding requirement (about 20-25 g per day) compared to chicken (120-130 g per day) (Ani et al., 2009). Quail attain a market weight of 140-180 g between 5-8 weeks of age and reaches peak egg production at the age of 5-8 weeks (Garwood and Diehl, 1987). -

Connecting Species' Geographical Distributions to Environmental Variables

UC Riverside UC Riverside Previously Published Works Title Connecting species’ geographical distributions to environmental variables: range maps versus observed points of occurrence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5j41c8sv Journal Ecography, 43(6) ISSN 0906-7590 Authors Rotenberry, JT Balasubramaniam, P Publication Date 2020-06-01 DOI 10.1111/ecog.04871 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 43 1–17 ECOGRAPHY Research Connecting species’ geographical distributions to environmental variables: range maps versus observed points of occurrence John T. Rotenberry and Priya Balasubramaniam J. T. Rotenberry (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0864-1676) ✉ ([email protected]), Dept of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, Univ. of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN, USA. – P. Balasubramaniam, Reno, NV, USA. Ecography Connecting the geographical occurrence of a species with underlying environmental 43: 1–17, 2020 variables is fundamental for many analyses of life history evolution and for modeling doi: 10.1111/ecog.04871 species distributions for both basic and practical ends. However, raw distributional information comes principally in two forms: points of occurrence (specific geographi- Subject Editor: Jorge Soberon cal coordinates where a species has been observed), and expert-prepared range maps. Editor-in-Chief: Hanna Tuomisto Each form has potential short-comings: range maps tend to overestimate the true Accepted 13 February 2020 occurrence of a species, whereas occurrence points (because of their frequent non- random spatial distribution) tend to underestimate it. Whereas previous comparisons of the two forms have focused on how they may differ when estimating species rich- ness, less attention has been paid to the extent to which the two forms actually differ in their representation of a species’ environmental associations.