7 Social Behavior and Vocalizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nogth AMERICAN BIRDS

CHECK-LIST OF NOgTH AMERICAN BIRDS The Speciesof Birds of North America from the Arctic through Panama, Including the West Indies and Hawaiian Islands PREPARED BY THE COMMITTEE ON CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE OF THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION SEVENTH EDITION 1998 Zo61ogical nomenclature is a means, not an end, to Zo61ogical Science PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION 1998 Copyright 1998 by The American Ornithologists' Union All rights reserved, except that pages or sections may be quoted for research purposes. ISBN Number: 1-891276-00-X Preferred citation: American Ornithologists' Union. 1983. Check-list of North American Birds. 7th edition. American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, D.C. Printed by Allen Press, Inc. Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A. CONTENTS DEDICATION ...................................................... viii PREFACE ......................................................... ix LIST OF SPECIES ................................................... xvii THE CHECK-LIST ................................................... 1 I. Tinamiformes ............................................. 1 1. Tinamidae: Tinamous .................................. 1 II. Gaviiformes .............................................. 3 1. Gaviidae: Loons ....................................... 3 III. Podicipediformes.......................................... 5 1. Podicipedidae:Grebes .................................. 5 IV. Procellariiformes .......................................... 9 1. Diomedeidae: Albatrosses ............................. -

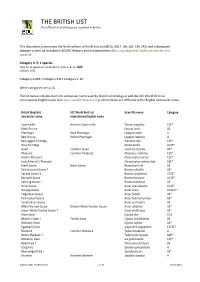

THE BRITISH LIST the Official List of Bird Species Recorded in Britain

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC Reports and announcements (bou.org.uk/british-list/bourc-reports-and- papers/). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 623 at 8 June 2021 Category A 605 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British ornithologists and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Capercaillie Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus C3E* Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix AE Ptarmigan Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta A Red Grouse Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus A Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa C1E* Grey Partridge Perdix perdix AC2E* Quail Common Quail Coturnix coturnix AE* Pheasant Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus C1E* Golden Pheasant Chrysolophus pictus C1E* Lady Amherst’s Pheasant Chrysolophus amherstiae C6E* Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser -

The Sleeping Habit of the Willow Ptarmigan

638 GeneralNotes [Oct.[Auk day the bird was found dead by Mr. Wilkin at the edge of the marsh. It had been shot and left by someoneunknown. The bird was turned over to New York Con- servation Department officers and has now been placed in the New York State Museum collection. The bird was a female in excellentbreeding-plumage condition and contained eggs. It weighed 11s/{ pounds, had a wing-spreadof 97 inches,and a length of 54 inches. It was examined in the flesh by both authors of this note.-- GORDO• M. M•AD•, M.D., Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester,New York, A•D C•,a¾•ro• B. S•ao•ms, Supt. of ConservationEducation, Albany, New York. The sleeping habit of the Willow Ptarmigan.--A frequent statement regard- ing the Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopuslagopus) is that in winter when it goesto roost it drops from flight into the snow, completely burying itself and leaving no tracks that might lead predators to it. E. W. Nelson made this observation years ago in Alaska, and it is given also by Sandys and Van Dyke in their book, 'Upland Game Birds.' Bent (U.S. Nat. Mus. Bull., 162: 194, 1932) in writing on Allen's Ptarmigan of Newfoundland, quotes •I. R. Whitaker as stating that they roost in a shallow scratchingin the snow and are frequently buried by drifts and imprisonedto their death. On Southampton Island, Sutton records the Willow Ptarmigan as roosting and feeding in the same area without attempt at concealment. One night seven slept for the night in sevenconsecutive footprints of his track acrossthe snow. -

Alaska Birds & Wildlife

Alaska Birds & Wildlife Pribilof Islands - 25th to 27th May 2016 (4 days) Nome - 28th May to 2nd June 2016 (5 days) Barrow - 2nd to 4th June 2016 (3 days) Denali & Kenai Peninsula - 5th to 13th June 2016 (9 days) Scenic Alaska by Sid Padgaonkar Trip Leader(s): Forrest Rowland and Forrest Davis RBT Alaska – Trip Report 2016 2 Top Ten Birds of the Tour: 1. Smith’s Longspur 2. Spectacled Eider 3. Bluethroat 4. Gyrfalcon 5. White-tailed Ptarmigan 6. Snowy Owl 7. Ivory Gull 8. Bristle-thighed Curlew 9. Arctic Warbler 10. Red Phalarope It would be very difficult to accurately describe a tour around Alaska - without drowning the narrative in superlatives to the point of nuisance. Not only is it an inconceivably huge area to describe, but the habitats and landscapes, though far north and less biodiverse than the tropics, are completely unique from one portion of the tour to the next. Though I will do my best, I will fail to encapsulate what it’s like to, for example, watch a coastal glacier calving into the Pacific, while being observed by Harbour Seals and on-looking Murrelets. I can’t accurately describe the sense of wilderness felt looking across the vast glacial valleys and tundra mountains of Nome, with Long- tailed Jaegers hovering overhead, a Rock Ptarmigan incubating eggs near our feet, and Muskoxen staring at us strangers to these arctic expanses. Finally, there is Denali: squinting across jagged snowy ridges that tower above 10,000 feet, mere dwarfs beneath Denali standing 20,300 feet high, making everything else in view seem small, even toy-like, by comparison. -

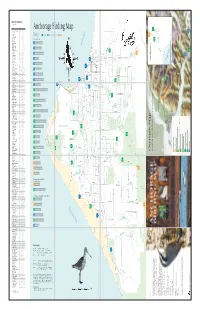

Anchorage Birding Map ❏ Common Redpoll* C C C C ❄ ❏ Hoary Redpoll R ❄ ❏ Pine Siskin* U U U U ❄ Additional References: Anchorage Audubon Society

BIRDS OF ANCHORAGE (Knik River to Portage) SPECIES SP S F W ❏ Greater White-fronted Goose U R ❏ Snow Goose U ❏ Cackling Goose R ? ❏ Canada Goose* C C C ❄ ❏ Trumpeter Swan* U r U ❏ Tundra Swan C U ❏ Gadwall* U R U ❄ ❏ Eurasian Wigeon R ❏ American Wigeon* C C C ❄ ❏ Mallard* C C C C ❄ ❏ Blue-winged Teal r r ❏ Northern Shoveler* C C C ❏ Northern Pintail* C C C r ❄ ❏ Green-winged Teal* C C C ❄ ❏ Canvasback* U U U ❏ Redhead U R R ❄ ❏ Ring-necked Duck* U U U ❄ ❏ Greater Scaup* C C C ❄ ❏ Lesser Scaup* U U U ❄ ❏ Harlequin Duck* R R R ❄ ❏ Surf Scoter R R ❏ White-winged Scoter R U ❏ Black Scoter R ❏ Long-tailed Duck* R R ❏ Bufflehead U U ❄ ❏ Common Goldeneye* C U C U ❄ ❏ Barrow’s Goldeneye* U U U U ❄ ❏ Common Merganser* c R U U ❄ ❏ Red-breasted Merganser u R ❄ ❏ Spruce Grouse* U U U U ❄ ❏ Willow Ptarmigan* C U U c ❄ ❏ Rock Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ White-tailed Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ Red-throated Loon* R R R ❏ Pacific Loon* U U U ❏ Common Loon* U R U ❏ Horned Grebe* U U C ❏ Red-necked Grebe* C C C ❏ Great Blue Heron r r ❄ ❏ Osprey* R r R ❏ Bald Eagle* C U U U ❄ ❏ Northern Harrier* C U U ❏ Sharp-shinned Hawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Northern Goshawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Red-tailed Hawk* U R U ❏ Rough-legged Hawk U R ❏ Golden Eagle* U R U ❄ ❏ American Kestrel* R R ❏ Merlin* U U U R ❄ ❏ Gyrfalcon* R ❄ ❏ Peregrine Falcon R R ❄ ❏ Sandhill Crane* C u U ❏ Black-bellied Plover R R ❏ American Golden-Plover r r ❏ Pacific Golden-Plover r r ❏ Semipalmated Plover* C C C ❏ Killdeer* R R R ❏ Spotted Sandpiper* C C C ❏ Solitary Sandpiper* u U U ❏ Wandering Tattler* u R R ❏ Greater Yellowlegs* -

A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes)

Galliform Baraminology 1 Running Head: GALLIFORM BARAMINOLOGY A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes) Michelle McConnachie A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2007 Galliform Baraminology 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Timothy R. Brophy, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Marcus R. Ross, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Harvey D. Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Judy R. Sandlin, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Program Director ______________________________ Date Galliform Baraminology 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, without Whom I would not have had the opportunity of being at this institution or producing this thesis. I would also like to thank my entire committee including Dr. Timothy Brophy, Dr. Marcus Ross, Dr. Harvey Hartman, and Dr. Judy Sandlin. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brophy who patiently guided me through the entire research and writing process and put in many hours working with me on this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their interest in this project and Robby Mullis for his constant encouragement. Galliform Baraminology 4 Abstract This study investigates the number of galliform bird holobaramins. Criteria used to determine the members of any given holobaramin included a biblical word analysis, statistical baraminology, and hybridization. The biblical search yielded limited biosystematic information; however, since it is a necessary and useful part of baraminology research it is both included and discussed. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Peacock-Pheasants (Galliformes: Polyplectron Spp.) Indicates Loss and Reduction of Ornamental Traits and Display Behaviours

Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (2001), 73: 187–198. With 3 figures doi:10.1006/bijl.2001.0536, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on A molecular phylogeny of the peacock-pheasants (Galliformes: Polyplectron spp.) indicates loss and reduction of ornamental traits and display behaviours REBECCA T. KIMBALL1,2∗, EDWARD L. BRAUN1,3, J. DAVID LIGON1, VITTORIO LUCCHINI4 and ETTORE RANDI4 1Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA 2Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 3Department of Plant Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 4Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca` Fornacetta 9, 40064 Ozzano dell’Emilia (BO), Italy Received 4 September 2000; accepted for publication 3 March 2001 The South-east Asian pheasant genus Polyplectron is comprised of six or seven species which are characterized by ocelli (ornamental eye-spots) in all but one species, though the sizes and distribution of ocelli vary among species. All Polyplectron species have lateral displays, but species with ocelli also display frontally to females, with feathers held erect and spread to clearly display the ocelli. The two least ornamented Polyplectron species, one of which completely lacks ocelli, have been considered the primitive members of the genus, implying that ocelli are derived. We examined this hypothesis phylogenetically using complete mitochondrial cytochrome b and control region sequences, as well as sequences from intron G in the nuclear ovomucoid gene, and found that the two least ornamented species are in fact the most recently evolved. Thus, the absence and reduction of ocelli and other ornamental traits in Polyplectronare recent losses. -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

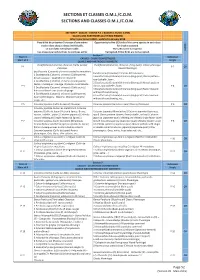

Section P, Quales and Partridges.Cdr

SECTIONS ET CLASSES O.M.J./C.O.M. SECTIONS AND CLASSES O.M.J./C.O.M. SECTION P - CAILLES - COLINS P.E. ( BAGUES 1 ET/OU 2 ANS) QUAILS AND PARTRIDGES (1/2 YEARS RINGED) Mise à jour Janvier 2018 - updated in January 2018 Possibilité de présenter 5 oiseaux d'une même Opportunity to five (5) birds of the same species in each class C A espèce dans chaque classe individuelle. for singles accepted GE Le nom lan est indispensable. The Lan name is required. S Les oiseaux panachés-frisés ne sont pas admis Variegated-frilled birds are not accepted. Secon P Stam 4 Individuel CAILLES - COLINS DOMESTIQUES Stam of 4 Single QUAILS AND PARTRIDGES DOMESTIC Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) Excalfactoria(coturnix) chinensis. (King quail) Classic phenoype P 1 P 2 O1 Classique Classic Phenotype Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis toutes les mutaons Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis All mutaons: 1 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 1 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Classic paern : Dessin sauvage : Opale,Brune etIsabelle . opal,Isabelle , fawn.. 2 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 2 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Mosaïc paern Facteur mosaïque : sauvage, Opale,Brune etIsabelle P 3 classic, opal,Isabelle , fawn. P 4 O1 3 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 3 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Factor melanic Patron mélanisé sans dessin de gorge without throat drawing 4 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 4 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis -

Evaluation of a Density Index for Territorial Male Hazel Grouse Bonasa Bonasia in Spring and Autumn

Ornis Fennica 68 :57-65. 1991 Evaluation of a density index for territorial male Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia in spring and autumn Jon E. Swenson Swenson, J. E., Department of Zoology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E9, Canada, and Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Grimsö Wildlife Research Station, S-730 91 Riddarhyttan, Sweden (correspondence to Swedish address) . Received 14 September 1990, accepted 10 January 1991 A density index for territorial male Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia in spring and au- tumn is presented and evaluated. One whistles with a hunter's whistle every 30 seconds for 6 minutes from census points located at 150-m intervals within the area to be censused, and responding Hazel Grouse are counted. Counts were conducted throughout days with little or no wind. The number of counted males was significantly and linearly correlated with the number of known territorial males on an intensive study area. There, 82% of the territorial males responded and were counted. Response rate appeared to be independent of density, based on counts in areas with a 20-fold variation in densities. When censuses were repeated, both results were similar. Within the conditions of these counts, no effects of weather or date were found. However, Hazel Grouse responded less at midday. Using this method, one can count Hazel Grouse at a rate of about 5 minutes per ha along transects and 5-9 minutes per ha on blocks of habitat, depending on plot size. I recommend that censuses be conducted during 4-5 weeks prior to laying in spring and during 4-5 weeks after brood dissolution in autumn . -

Comparison of Cytochrome B Region Among Chinese Painted Quail, Wild-Strain Quail, and White Broiler Chicken Based on PCR-RFLP Analysis

287 Comparison of Cytochrome b Region Among Chinese Painted Quail, Wild-Strain Quail, and White Broiler Chicken Based on PCR-RFLP Analysis Xiang-Jun SHEN1),Hidenori SUZUKI2)*, Masaoki TSUDZUKI3), Shin'ichiITO2) and Takao NAKAMURA2)** 1)The United Graduate School of AgriculturalScience , 2)Faculty of Agriculture, GifuUniversity, Gifu 501-1193 3)Faculty of AppliedBiological Science , Hiroshima University,Higashi-Hiroshima 739-8528 PCR-RFLPanalysis was used to examine 1,075 bp cytochromeb (Cyt b) region of mtDNAineach of 20birds of Chinese painted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis), wild-strain Japanesequail (Coturnix japonica), and white broiler chicken (Gallus gallus). The total Cytb ampliconwas digested with 10 restriction endonucleases, andits electrophoretic patternwas investigated. Ten kinds of restrictionenzyme digestions were identical among20 individuals ineach of the three species. No variation was observed in the 10 kindsof enzymedigestions among different individuals within the threespecies in- vestigated.The different specific electrophoretic patterns, haplotypes, and total restric- tionfragments were observed in eachof the three species belonging tothe same family Phasianidae.The result representatives the evolutionarygenetic characteristics of RFLPof cytochromeb region in thethree different species, and indicated the genetic diversityamong the three genuses of the family Phasianidae, and genetic identity within eachof thespecies. The result could be used for the identification of different species withinfamily Phasianidae and as a referenceofphysical map for cytochrome b gene. (Jpn.Poult. Sci., 36: 287-294, 1999) Keywords:PCR-RFLP, cytochrome b,Excalfactoria chinensis, Coturnix japonica, Gallus gallus Introduction Chinesepainted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) belongs to the orderGalliformes, family Phasianidae,and genus Excalfactoria,(YAMASHINA, 1986). Japanese quail belongsto the samefamily Phasianidae, a different genus Coturnix (CRAWFORD, 1990). -

Rapid Communication- Primer Design and Sequence Information for Cytochrome B Gene in the Chinese Painted Quail (Excalfactoria C

-Rapid Communication- Primer Design and Sequence Information for Cytochrome b Gene in the Chinese Painted Quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) Xiang-Jun SHEN, Masaoki TSUDZUKIa, Takao NAKAMURAb The United Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Gifu University, Gifu-shi 501-1193, Japan Faculty of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima-shi 739-8528,a Japan bFaculty of Agriculture , Gifu University, Gifu-shi 501-1193, Japan (Received April 21, 1999; Accepted May 15, 1999) Abstract In accordance with the chicken and quail mitochondrialDNA sequences,three pairs of primers encompassing light and heavy strand (L14832, L15269, L15500, H15924, H15497, and H16207) with high specificity were designed, synthesized, and used for amplification and sequencing of cytochrome b (Cyt b) gene. The PCR products were sequenced by the direct-sequencing method. The Chinese painted quail cytochrome b gene consisted of 1,143bp nucleotides (base composition: 327 A; 399 C; 281 T and 136 G), encoded for a 380 amino acid sequence, and showed 89.0%, 86.4%, and 86.2%, homology with nucleotide sequences of Japanese quail, silky fowl, and White Leghorn chicken, respectively. The homology of the amino acid sequence of the cytochrome b gene of Chinese painted quail showed 98.2%, 95.3%, and 95.3% with those of Japanese quail, silky fowl, and White Leghorn chicken, respectively. The sequencesreported in this paper have been depositedin the GenBank database(Accession No. AF109217). Animal Science Journal 70 (4): 240-242,1999 Key words: Chinese painted quail,Excalfactoria chinensis, Cytochromeb, Sequence,Homology Chinese painted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) belongs the test: to the order Galliformes, family Phasianidae, genus (1) L14832: 5'-TACCTGGGTTCCTTCGCCCT-3' Excalfactoria5),and it is the smallest species in the family (2) H15497: 5'-TGTAGGAAGGTGAGTGGAT-3' Phasianidae.