Revision of Molt and Plumage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sage-Grouse Hunting Season

CHAPTER 11 UPLAND GAME BIRD AND SMALL GAME HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302 and § 23-2-105 (d). Section 2. Hunting Regulations. (a) Bag and Possession Limit. Only one (1) daily bag limit of each species of upland game birds and small game may be taken per day regardless of the number of hunt areas hunted in a single day. When hunting more than one (1) hunt area, a person’s daily and possession limits shall be equal to, but shall not exceed, the largest daily and possession limit prescribed for any one (1) of the specified hunt areas in which the hunting and possession occurs. (b) Evidence of sex and species shall remain naturally attached to the carcass of any upland game bird in the field and during transportation. For pheasant, this shall include the feathered head, feathered wing or foot. For all other upland game bird species, this shall include one fully feathered wing. (c) No person shall possess or use shot other than nontoxic shot for hunting game birds and small game with a shotgun on the Commission’s Table Mountain and Springer wildlife habitat management areas and on all national wildlife refuges open for hunting. (d) Required Clothing. Any person hunting pheasants within the boundaries of any Wyoming Game and Fish Commission Wildlife Habitat Management Area, or on Bureau of Reclamation Withdrawal lands bordering and including Glendo State Park, shall wear in a visible manner at least one (1) outer garment of fluorescent orange or fluorescent pink color which shall include a hat, shirt, jacket, coat, vest or sweater. -

Importance of Tactile and Visual Stimuli of Eggs and Nest for Termination of Egg Laying of Red Junglefowl

The Auk 112(2):483-488, 1995 IMPORTANCE OF TACTILE AND VISUAL STIMULI OF EGGS AND NEST FOR TERMINATION OF EGG LAYING OF RED JUNGLEFOWL THEO MEIJER Departmentof Ethology,University of BieIefeld,P.O. Box100131, 33501Bielefeld, Germany ABSTRACT.--Experimentswere conductedto separatethe influence of tactile and visual stimuli emanating from the nest or eggs on the development of incubation behavior, the terminationof egg laying, and the determinationof clutchsize. Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus spadiceus)hens, whose eggswere left inside the nest (experiment 1), receivedboth tactile and visualinformation, remained in the nestbox longer,and stoppedlaying after eight days (or sixeggs). Sixteen or 17females incubated. Leaving only the firstegg in the nest(experiment 2) gavesimilar results. When the eggslaid were placedunder a wire-meshbasket (experiment 3) suchthat the hen couldsee but not touchthe accumulatingeggs, laying stopped two days (or one egg) later than in experiment1, and mosthens "incubated"on the empty nestuntil the nestbox wasremoved. Surprisingly, when eggswere continuallyremoved (experiment 4), hensalso incubated progressively more, stopped laying after two weeks(or nine eggs), and then sat on the empty nest for one or more days. Stimulation of the brood patch by the nest alone led to more incubationand to termination of egg laying. Visual stimuli alone providedby eggsaccelerated both processesand were sufficientfor one-half of the hens to maintainfull incubationbehavior. Red Junglefowl do not appearto judgeclutch size visually. Received9 December1993, accepted25 February1994. DURING THE BREEDINGSEASON, a female has to nest. The few experimentsby which tactile in- make two important "decisions":when to start formation coming from the brood patch was laying, and when to stop laying. -

Gyrfalcon Diet in Central West Greenland During the Nesting Period

The Condor 105:528±537 q The Cooper Ornithological Society 2003 GYRFALCON DIET IN CENTRAL WEST GREENLAND DURING THE NESTING PERIOD TRAVIS L. BOOMS1,3 AND MARK R. FULLER2 1Boise State University Raptor Research Center, 1910 University Drive, Boise, ID 83725 2USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 970 Lusk St., Boise, ID 83706 Abstract. We studied food habits of Gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) nesting in central west Greenland in 2000 and 2001 using three sources of data: time-lapse video (3 nests), prey remains (22 nests), and regurgitated pellets (19 nests). These sources provided different information describing the diet during the nesting period. Gyrfalcons relied heavily on Rock Ptarmigan (Lagopus mutus) and arctic hares (Lepus arcticus). Combined, these species con- tributed 79±91% of the total diet, depending on the data used. Passerines were the third most important group. Prey less common in the diet included waterfowl, arctic fox pups (Alopex lagopus), shorebirds, gulls, alcids, and falcons. All Rock Ptarmigan were adults, and all but one arctic hare were young of the year. Most passerines were ¯edglings. We observed two diet shifts, ®rst from a preponderance of ptarmigan to hares in mid-June, and second to passerines in late June. The video-monitored Gyrfalcons consumed 94±110 kg of food per nest during the nestling period, higher than previously estimated. Using a combi- nation of video, prey remains, and pellets was important to accurately document Gyrfalcon diet, and we strongly recommend using time-lapse video in future diet studies to identify biases in prey remains and pellet data. Key words: camera, diet, Falco rusticolus, food habits, Greenland, Gyrfalcon, time-lapse video. -

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

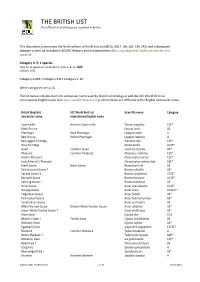

THE BRITISH LIST the Official List of Bird Species Recorded in Britain

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC Reports and announcements (bou.org.uk/british-list/bourc-reports-and- papers/). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 623 at 8 June 2021 Category A 605 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British ornithologists and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Capercaillie Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus C3E* Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix AE Ptarmigan Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta A Red Grouse Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus A Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa C1E* Grey Partridge Perdix perdix AC2E* Quail Common Quail Coturnix coturnix AE* Pheasant Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus C1E* Golden Pheasant Chrysolophus pictus C1E* Lady Amherst’s Pheasant Chrysolophus amherstiae C6E* Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser -

The Sleeping Habit of the Willow Ptarmigan

638 GeneralNotes [Oct.[Auk day the bird was found dead by Mr. Wilkin at the edge of the marsh. It had been shot and left by someoneunknown. The bird was turned over to New York Con- servation Department officers and has now been placed in the New York State Museum collection. The bird was a female in excellentbreeding-plumage condition and contained eggs. It weighed 11s/{ pounds, had a wing-spreadof 97 inches,and a length of 54 inches. It was examined in the flesh by both authors of this note.-- GORDO• M. M•AD•, M.D., Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester,New York, A•D C•,a¾•ro• B. S•ao•ms, Supt. of ConservationEducation, Albany, New York. The sleeping habit of the Willow Ptarmigan.--A frequent statement regard- ing the Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopuslagopus) is that in winter when it goesto roost it drops from flight into the snow, completely burying itself and leaving no tracks that might lead predators to it. E. W. Nelson made this observation years ago in Alaska, and it is given also by Sandys and Van Dyke in their book, 'Upland Game Birds.' Bent (U.S. Nat. Mus. Bull., 162: 194, 1932) in writing on Allen's Ptarmigan of Newfoundland, quotes •I. R. Whitaker as stating that they roost in a shallow scratchingin the snow and are frequently buried by drifts and imprisonedto their death. On Southampton Island, Sutton records the Willow Ptarmigan as roosting and feeding in the same area without attempt at concealment. One night seven slept for the night in sevenconsecutive footprints of his track acrossthe snow. -

2011, Article ID 423938, 16 Pages Doi:10.4061/2011/423938

SAGE-Hindawi Access to Research International Journal of Evolutionary Biology Volume 2011, Article ID 423938, 16 pages doi:10.4061/2011/423938 Research Article A Macroevolutionary Perspective on Multiple Sexual Traits in the Phasianidae (Galliformes) Rebecca T. Kimball, Colette M. St. Mary, and Edward L. Braun Department of Biology, University of Florida, P.O. Box 118525, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Rebecca T. Kimball, [email protected]fl.edu Received 2 October 2010; Accepted 26 February 2011 Academic Editor: Rob Kulathinal Copyright © 2011 Rebecca T. Kimball et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Traits involved in sexual signaling are ubiquitous among animals. Although a single trait appears sufficient to convey information, many sexually dimorphic species exhibit multiple sexual signals, which may be costly to signalers and receivers. Given that one signal may be enough, there are many microevolutionary hypotheses to explain the evolution of multiple signals. Here we extend these hypotheses to a macroevolutionary scale and compare those predictions to the patterns of gains and losses of sexual dimorphism in pheasants and partridges. Among nine dimorphic characters, including six intersexual signals and three indicators of competitive ability, all exhibited both gains and losses of dimorphism within the group. Although theories of intersexual selection emphasize gain and elaboration, those six characters exhibited greater rates of loss than gain; in contrast, the competitive traits showed a slight bias towards gains. The available models, when examined in a macroevolutionary framework, did not yield unique predictions, making it difficult to distinguish among them. -

Nesting Behavior of Female White-Tailed Ptarmigan in Colorado

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 215 Condor, 81:215-217 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1070 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF FEMALE settling on the clutches. By lifting the hens off their WHITE-TAILED PTARMIGAN nests, we learned that eggs were laid almost immedi- ately after settling. IN COLORADO After eggs were laid, the hens remained relatively inactive until they prepared to depart from the nest. Observations of six hens in 1975 indicated that they KENNETH M. GIESEN remained on the nest for longer periods as the clutch AND approached completion. One hen depositing her sec- ond egg remained on her nest for 44 min, whereas CLAIT E. BRAUN another, depositing the fifth egg of a six-egg clutch, remained on the nest more than 280 min. Three hens remained on their nests 84 to 153 min when laying Few detailed observations on behavior of nesting their second or third eggs. Spruce Grouse also show grouse have been reported. Notable exceptions are this pattern of nest attentiveness (McCourt et al. those of SchladweiIer (1968) and Maxson (1977) 1973). who studied feeding behavior and activity patterns of Before departing from the nest, the hen began to Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) in Minnesota, and peck at vegetation and place it at the rim of the McCourt et al. ( 1973) who documented nest atten- nest, or throw it over her back. This behavior lasted tiveness of Spruce Grouse (Canachites canudensis) in 34, 40 and 64 min for three hens. Vegetation was southwestern Alberta. White-tailed Ptarmigan (Lugo- deposited on the nest at the rate of 20 pieces per pus Zeucurus) have been intensively studied in Colo- minute. -

Wild Turkey Education Guide

Table of Contents Section 1: Eastern Wild Turkey Ecology 1. Eastern Wild Turkey Quick Facts………………………………………………...pg 2 2. Eastern Wild Turkey Fact Sheet………………………………………………….pg 4 3. Wild Turkey Lifecycle……………………………………………………………..pg 8 4. Eastern Wild Turkey Adaptations ………………………………………………pg 9 Section 2: Eastern Wild Turkey Management 1. Wild Turkey Management Timeline…………………….……………………….pg 18 2. History of Wild Turkey Management …………………...…..…………………..pg 19 3. Modern Wild Turkey Management in Maryland………...……………………..pg 22 4. Managing Wild Turkeys Today ……………………………………………….....pg 25 Section 3: Activity Lesson Plans 1. Activity: Growing Up WILD: Tasty Turkeys (Grades K-2)……………..….…..pg 33 2. Activity: Calling All Turkeys (Grades K-5)………………………………..…….pg 37 3. Activity: Fit for a Turkey (Grades 3-5)…………………………………………...pg 40 4. Activity: Project WILD adaptation: Too Many Turkeys (Grades K-5)…..…….pg 43 5. Activity: Project WILD: Quick, Frozen Critters (Grades 5-8).……………….…pg 47 6. Activity: Project WILD: Turkey Trouble (Grades 9-12………………….……....pg 51 7. Activity: Project WILD: Let’s Talk Turkey (Grades 9-12)..……………..………pg 58 Section 4: Additional Activities: 1. Wild Turkey Ecology Word Find………………………………………….…….pg 66 2. Wild Turkey Management Word Find………………………………………….pg 68 3. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 70 4. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 71 5. Turkey Color-by-Letter……………………………………..…………………….pg 72 6. Five Little Turkeys Song Sheet……. ………………………………………….…pg 73 7. Thankful Turkey…………………..…………………………………………….....pg 74 8. Graph-a-Turkey………………………………….…………………………….…..pg 75 9. Turkey Trouble Maze…………………………………………………………..….pg 76 10. What Animals Made These Tracks………………………………………….……pg 78 11. Drinking Straw Turkey Call Craft……………………………………….….……pg 80 Section 5: Wild Turkey PowerPoint Slide Notes The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. -

Reproductive Ecology of Tibetan Eared Pheasant Crossoptilon Harmani in Scrub Environment, with Special Reference to the Effect of Food

Ibis (2003), 145, 657–666 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Reproductive ecology of Tibetan Eared Pheasant Crossoptilon harmani in scrub environment, with special reference to the effect of food XIN LU1* & GUANG-MEI ZHENG2 1Department of Zoology, College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China 2Department of Ecology, College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China We studied the nesting ecology of two groups of the endangered Tibetan Eared Pheasants Crossoptilon harmani in scrub environments near Lhasa, Tibet, during 1996 and 1999–2001. One group received artificial food from a nunnery prior to incubation whereas the other fed on natural food. This difference in the birds’ nutritional history allowed us to assess the effects of food on reproduction. Laying occurred between mid-April and early June, with a peak at the end of April or early May. Eggs were laid around noon. Adult females produced one clutch per year. Clutch size averaged 7.4 eggs (4–11). Incubation lasted 24–25 days. We observed a higher nesting success (67.7%) than reported for other eared pheasants. Pro- visioning had no significant effect on the timing of clutch initiation or nesting success, and a weak effect on egg size and clutch size (explaining 8.2% and 9.1% of the observed variation, respectively). These results were attributed to the observation that the unprovisioned birds had not experienced local food shortage before laying, despite spending more time feeding and less time resting than the provisioned birds. Nest-site selection by the pheasants was non-random with respect to environmental variables. Rock-cavities with an entrance aver- aging 0.32 m2 in size and not deeper than 1.5 m were greatly preferred as nest-sites. -

Alaska Birds & Wildlife

Alaska Birds & Wildlife Pribilof Islands - 25th to 27th May 2016 (4 days) Nome - 28th May to 2nd June 2016 (5 days) Barrow - 2nd to 4th June 2016 (3 days) Denali & Kenai Peninsula - 5th to 13th June 2016 (9 days) Scenic Alaska by Sid Padgaonkar Trip Leader(s): Forrest Rowland and Forrest Davis RBT Alaska – Trip Report 2016 2 Top Ten Birds of the Tour: 1. Smith’s Longspur 2. Spectacled Eider 3. Bluethroat 4. Gyrfalcon 5. White-tailed Ptarmigan 6. Snowy Owl 7. Ivory Gull 8. Bristle-thighed Curlew 9. Arctic Warbler 10. Red Phalarope It would be very difficult to accurately describe a tour around Alaska - without drowning the narrative in superlatives to the point of nuisance. Not only is it an inconceivably huge area to describe, but the habitats and landscapes, though far north and less biodiverse than the tropics, are completely unique from one portion of the tour to the next. Though I will do my best, I will fail to encapsulate what it’s like to, for example, watch a coastal glacier calving into the Pacific, while being observed by Harbour Seals and on-looking Murrelets. I can’t accurately describe the sense of wilderness felt looking across the vast glacial valleys and tundra mountains of Nome, with Long- tailed Jaegers hovering overhead, a Rock Ptarmigan incubating eggs near our feet, and Muskoxen staring at us strangers to these arctic expanses. Finally, there is Denali: squinting across jagged snowy ridges that tower above 10,000 feet, mere dwarfs beneath Denali standing 20,300 feet high, making everything else in view seem small, even toy-like, by comparison. -

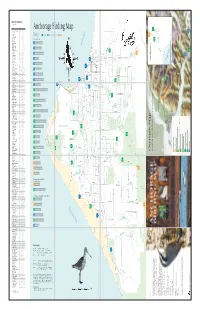

Anchorage Birding Map ❏ Common Redpoll* C C C C ❄ ❏ Hoary Redpoll R ❄ ❏ Pine Siskin* U U U U ❄ Additional References: Anchorage Audubon Society

BIRDS OF ANCHORAGE (Knik River to Portage) SPECIES SP S F W ❏ Greater White-fronted Goose U R ❏ Snow Goose U ❏ Cackling Goose R ? ❏ Canada Goose* C C C ❄ ❏ Trumpeter Swan* U r U ❏ Tundra Swan C U ❏ Gadwall* U R U ❄ ❏ Eurasian Wigeon R ❏ American Wigeon* C C C ❄ ❏ Mallard* C C C C ❄ ❏ Blue-winged Teal r r ❏ Northern Shoveler* C C C ❏ Northern Pintail* C C C r ❄ ❏ Green-winged Teal* C C C ❄ ❏ Canvasback* U U U ❏ Redhead U R R ❄ ❏ Ring-necked Duck* U U U ❄ ❏ Greater Scaup* C C C ❄ ❏ Lesser Scaup* U U U ❄ ❏ Harlequin Duck* R R R ❄ ❏ Surf Scoter R R ❏ White-winged Scoter R U ❏ Black Scoter R ❏ Long-tailed Duck* R R ❏ Bufflehead U U ❄ ❏ Common Goldeneye* C U C U ❄ ❏ Barrow’s Goldeneye* U U U U ❄ ❏ Common Merganser* c R U U ❄ ❏ Red-breasted Merganser u R ❄ ❏ Spruce Grouse* U U U U ❄ ❏ Willow Ptarmigan* C U U c ❄ ❏ Rock Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ White-tailed Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ Red-throated Loon* R R R ❏ Pacific Loon* U U U ❏ Common Loon* U R U ❏ Horned Grebe* U U C ❏ Red-necked Grebe* C C C ❏ Great Blue Heron r r ❄ ❏ Osprey* R r R ❏ Bald Eagle* C U U U ❄ ❏ Northern Harrier* C U U ❏ Sharp-shinned Hawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Northern Goshawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Red-tailed Hawk* U R U ❏ Rough-legged Hawk U R ❏ Golden Eagle* U R U ❄ ❏ American Kestrel* R R ❏ Merlin* U U U R ❄ ❏ Gyrfalcon* R ❄ ❏ Peregrine Falcon R R ❄ ❏ Sandhill Crane* C u U ❏ Black-bellied Plover R R ❏ American Golden-Plover r r ❏ Pacific Golden-Plover r r ❏ Semipalmated Plover* C C C ❏ Killdeer* R R R ❏ Spotted Sandpiper* C C C ❏ Solitary Sandpiper* u U U ❏ Wandering Tattler* u R R ❏ Greater Yellowlegs*