Europe's Huntable Birds a Review of Status and Conservation Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keeping Pheasants

KKKEEEEEEPPPIIINNNGGG PPPHHHEEEAAASSSAAANNNTTTSSS AAASSS AAA HHHOOOBBBBBBYYY Text and photos: Jan Willem Schrijvers Photo above: Siamese Fireback pheasant male(Lophura diardi). ORIGIN AND LIFESTYLE OF THE WILD PHEASANT Pheasants are wild gallinaceous birds all originating in Asia. One exception is the Congo peacock from Africa. (The pheasants also include game fowl and peacocks.) Each species has its own characteristics and life habits. There are species that live in tropical rain forests, but there are species that live in the mountains, on cold plains. This is something to take in account when housing our pheasants (with or without a night coop, with or without heating). Most species live in and around the mountains with a woodland vegetation, where they can find lots of berries, greens and seeds. It is of utmost importance to first consider the habits and living conditions of the species you want to keep. Only with proper housing will these beautiful birds show to their fullest, and reproduce. PHEASANTS IN AVIARIES In the past there were some "pheasant farms" which mainly bred the common pheasant (also known as ring-neck pheasant). The birds on these farms were bred for sport hunting. They were released en masse in the autumn in the fields and other areas to be shot for the sport. Some escaped from the hunters and that is why today we can see wild pheasants roam our fields and woods. These pheasants have also succeeded in reproducing themselves, even though they are not native birds. The birds are also kept for their colourful feathers. Each year I see Prince Carnival walk again with the beautiful feathers of the Reeves's Pheasant at his cocked hat. -

Lowland Book 170618.Indd

Grey partridges are an “indicator species” for broader farmland biodiversity, because where they thrive, a range of other species tend to do well. © Markus Jenny 3. Grey partridge In the past, the wild grey partridge thrived on farmland, and was traditionally the main focus of shooting in the lowlands. Management for driven partridge shooting led to rising numbers during the 19th century; it involved comprehensive predator control in a farmed environment that provided good partridge habitat, with weedy cereal crops, traditional crop rotations including grass crops, small fields separated by hedges, fallows and waste ground. By contrast, grey partridge numbers have been falling in the UK throughout the second half of the 20th century, with the decline becoming most marked since the mid-1960s. To focus conservation efforts, the grey partridge was put on the UK Red Data List in 1990, became a priority species under the 1995 UK Biodiversity Action Plan36, and remains a red-listed Bird of Conservation Concern. Progress has been made in areas that make a commitment to partridge conservation, but overall the decline in their numbers continues. GWCT research on grey partridge declines in the 1960s and 1970s helped to establish the new field of agro-ecology, which is studying 38 39 The Knowledge ecology within farming systems. Scientific study moved from recording declines, to investigating the changes in the arable environment that were affecting partridges45–47. This work found that the causes of the grey partridge decline were directly or indirectly related to much wider declines in many aspects of farmland biodiversity. For instance, the UK government monitors national bird abundance through the British Trust for Ornithology’s Breeding Bird Survey, which has shown a 92% decline in numbers of grey partridge from 1967 to 2015, in conjunction with declines in many other species of farmland bird48. -

Gyrfalcon Diet in Central West Greenland During the Nesting Period

The Condor 105:528±537 q The Cooper Ornithological Society 2003 GYRFALCON DIET IN CENTRAL WEST GREENLAND DURING THE NESTING PERIOD TRAVIS L. BOOMS1,3 AND MARK R. FULLER2 1Boise State University Raptor Research Center, 1910 University Drive, Boise, ID 83725 2USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 970 Lusk St., Boise, ID 83706 Abstract. We studied food habits of Gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) nesting in central west Greenland in 2000 and 2001 using three sources of data: time-lapse video (3 nests), prey remains (22 nests), and regurgitated pellets (19 nests). These sources provided different information describing the diet during the nesting period. Gyrfalcons relied heavily on Rock Ptarmigan (Lagopus mutus) and arctic hares (Lepus arcticus). Combined, these species con- tributed 79±91% of the total diet, depending on the data used. Passerines were the third most important group. Prey less common in the diet included waterfowl, arctic fox pups (Alopex lagopus), shorebirds, gulls, alcids, and falcons. All Rock Ptarmigan were adults, and all but one arctic hare were young of the year. Most passerines were ¯edglings. We observed two diet shifts, ®rst from a preponderance of ptarmigan to hares in mid-June, and second to passerines in late June. The video-monitored Gyrfalcons consumed 94±110 kg of food per nest during the nestling period, higher than previously estimated. Using a combi- nation of video, prey remains, and pellets was important to accurately document Gyrfalcon diet, and we strongly recommend using time-lapse video in future diet studies to identify biases in prey remains and pellet data. Key words: camera, diet, Falco rusticolus, food habits, Greenland, Gyrfalcon, time-lapse video. -

Acoustic Monitoring of Night-Migrating Birds: a Progress Report

Acoustic Monitoring of Night-Migrating Birds: A Progress Report William R. Evans Kenneth V. Rosenberg Abstract—This paper discusses an emerging methodology that to give regular vocalizations in night migration are the vireos uses electronic technology to monitor vocalizations of night-migrat- (Vireonidae), flycatchers (Tyrannidae), and orioles (Icterinae). ing birds. On a good migration night in eastern North America, If a monitoring protocol is consistently maintained, an array thousands of call notes may be recorded from a single ground-based, of microphone stations can provide information on how the audio-recording station, and an array of recording stations across a species composition and number of vocal migrants vary across region may serve as a “recording net” to monitor a broad front of time and space. Such data have application for monitoring migration. Data from pilot studies in Florida, Texas, New York, and avian populations and identifying their migration routes. In British Columbia illustrate the potential of this technique to gather addition, detection and classification of distinctive call-types information that cannot be gathered by more conventional methods, is possible with computers (Mills 1995; Taylor 1995), thus such as mist-netting or diurnal counts. For example, the Texas information on bird populations might be gained automati- station detected a major migration of grassland sparrows, and a cally. In this paper, we summarize the current state of station in British Columbia detected hundreds of Swainson’s knowledge for identifying night-flight calls to species; present Thrushes; both phenomena were not detected with ground monitor- selected results from four ongoing studies that are monitoring ing efforts. -

Small Game Review “Issues and Concerns”

ONTARIO FEDERATION OF ANGLERS AND HUNTERS SMALL GAME REVIEW “ISSUES AND CONCERNS” PRELIMINARY INPUT FROM THE ONTARIO FEDERATION OF ANGLERS AND HUNTERS OCTOBER 2009 General and Preliminary O.F.A.H. Comments/Suggestions Purpose The purpose is to update and revise the small game hunting regulations and policies, under the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, with the view to: • reflect changes in populations and/or harvest pressure to ensure sustainability; • address significant knowledge gaps where there is a conservation concern; • optimize the ecological, social, economic and recreational benefits that accrue through sustainable hunting of small game birds and mammals; • refine management directions and establish broad targets/objectives; and • manage and prevent human-wildlife conflicts. Scope of Review The review should include the conservation and management of provincial game birds, small game mammals, and furbearers that are also hunted (e.g. red fox, raccoon). At this time, small game species with current management plans/policy (i.e. wild turkey, wolves) need not be a focus within this review. The harvest management of migratory birds is primarily a federal mandate, but the review should consider recommendations for the improved management of migratory birds where there is a clear provincial interest and mandate to do so (e.g. woodcock, sandhill cranes). The harvest of snapping turtles and bullfrogs is regulated under the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, but are not considered “small game” for the purpose of this review. Falconry should be recognized as a small and growing method of small game hunting within Ontario; however, it should be mentioned that its regulation is reviewed regularly through the Provincial Falconry Advisory Committee, so it will not be included within this general review. -

Nesting Behavior of Female White-Tailed Ptarmigan in Colorado

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 215 Condor, 81:215-217 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1070 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF FEMALE settling on the clutches. By lifting the hens off their WHITE-TAILED PTARMIGAN nests, we learned that eggs were laid almost immedi- ately after settling. IN COLORADO After eggs were laid, the hens remained relatively inactive until they prepared to depart from the nest. Observations of six hens in 1975 indicated that they KENNETH M. GIESEN remained on the nest for longer periods as the clutch AND approached completion. One hen depositing her sec- ond egg remained on her nest for 44 min, whereas CLAIT E. BRAUN another, depositing the fifth egg of a six-egg clutch, remained on the nest more than 280 min. Three hens remained on their nests 84 to 153 min when laying Few detailed observations on behavior of nesting their second or third eggs. Spruce Grouse also show grouse have been reported. Notable exceptions are this pattern of nest attentiveness (McCourt et al. those of SchladweiIer (1968) and Maxson (1977) 1973). who studied feeding behavior and activity patterns of Before departing from the nest, the hen began to Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) in Minnesota, and peck at vegetation and place it at the rim of the McCourt et al. ( 1973) who documented nest atten- nest, or throw it over her back. This behavior lasted tiveness of Spruce Grouse (Canachites canudensis) in 34, 40 and 64 min for three hens. Vegetation was southwestern Alberta. White-tailed Ptarmigan (Lugo- deposited on the nest at the rate of 20 pieces per pus Zeucurus) have been intensively studied in Colo- minute. -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

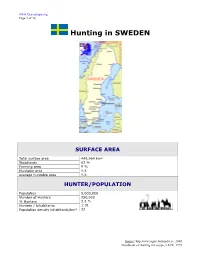

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

What Makes a Good Alien? Dealing with the Problems of Non-Native Wildfowl Tony (A

What makes a good alien? Dealing with the problems of non-native wildfowl Tony (A. D.) Fox Mandarin Ducks Aix galericulata Richard Allen ABSTRACT Humans have been introducing species outside their native ranges as a source of food for thousands of years, but introductions of wildfowl have increased dramatically since the 1700s.The most serious consequence of this has been the extinction of endemic forms as a result of hybridisation, although competition between alien and native forms may also contribute to species loss. Globally, non-native wildfowl have yet to cause major disruption to ecosystem functions; introduce new diseases and parasites; cause anything other than local conflicts to agricultural and economic interests; or create major health and safety issues in ways that differ from native forms. The fact that this has not happened is probably simply the result of good fortune, however, since many introduced plants and animals have had huge consequences for ecosystems and human populations.The potential cost of greater environmental and economic damage, species extinction, and threats to the genetic and species diversity of native faunas means that we must do all we can to stop the deliberate or accidental introduction of species outside their natural range. International legislation to ensure this is remarkably good, but domestic law is generally weak, as is the political will to enforce such regulations.The case of the Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis in Europe will show whether control of a problem taxon can be achieved and underlines the financial consequences of dealing with introduced aliens.This paper was originally presented as the 58th Bernard Tucker Memorial Lecture to the Oxford Ornithological Society and the Ashmolean Natural History Society, in November 2008. -

A Study of Food and Feeding Habits of Blue Peafowl, Pavo Cristatus Linnaeus, 1758 in District Kurukshetra, Haryana (India)

International Journal of Research Studies in Biosciences (IJRSB) Volume 2, Issue 6, July 2014, PP 11-16 ISSN 2349-0357 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0365 (Online) www.arcjournals.org A Study of Food and Feeding Habits of Blue Peafowl, Pavo Cristatus Linnaeus, 1758 in District Kurukshetra, Haryana (India) Girish Chopra, Tarsem Kumar Department of Zoology, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra-136119 (INDIA) [email protected] Summary: Present study was conducted to determine the food and feeding habits of blue peafowl in three study sites, namely, Saraswati plantation wildlife sanctuary (SPWS), Bir Sonti Reserve Forest (BSRF), and Jhrouli Kalan village (JKAL). Point count method (Blondel et al., 1981) was followed during periodic fortnightly visits to all the three selected study sites. The peafowls were observed to feed on flowers, fruits, leaves of 11, 8 and 8 plant species respectively. These were sighted to feed on Brassica compestris (flowers, leaves), Trifolium alexandarium (flowers, leaves), Triticum aestivum (flowers, leaves, fruits), Oryza sativa (flowers, leaves, fruits), Chenopodium album (flowers, leaves, fruits), Parthenium histerophoresus (flowers, leaves), Pisum sativum (flowers, leaves, fruits), Cicer arientum (flowers, leaves, fruits), Pyrus pyrifolia (flowers, fruits), Ficus benghalensis (flowers, fruits), Ficus rumphii (flowers, fruits). They were also observed feeding on insects in all three study sites and on remains of the snake bodies at the BSRF and JKAL study site. The findings revealed that the Indian peafowl, on one hand, functions as a predator of agricultural pests but, on the other hand, is itself a pest on agricultural crops. Keywords: Blue peafowl, Food, Feeding Habits, Herbs, Shrubs, Trees. 1. INTRODUCTION Birds are warm-blooded, bipedal, oviparous vertebrates characterized by bony beak, pneumatic bones, feathers and wings. -

A Wood-Concrete Nest Box to Study Burrow-Nesting Petrels

Bedolla-Guzmán et al.: Wood-concrete nest boxes to study petrels 249 A WOOD-CONCRETE NEST BOX TO STUDY BURROW-NESTING PETRELS YULIANA BEDOLLA-GUZMÁN1,2, JUAN F. MASELLO1, ALFONSO AGUIRRE-MUÑOZ2 & PETRA QUILLFELDT1 1Department of Animal Ecology and Systematics, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Heinrich-Buff-Ring 38, 35392 Giessen, Germany 2Grupo de Ecología y Conservación de Islas, A.C., Moctezuma 836, Zona Centro, 22800, Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico ([email protected]) Received 6 July 2016, accepted 31 August 2016 Artificial nests have been a useful research and conservation tool is an extended period of bi-parental care, and parents return to feed for a variety of petrel species (Podolsky & Kress 1989, Priddel & the chick only at night (Brooke 2004). Carlile 1995, De León & Mínguez 2003, Bolton et al. 2004). They facilitate observation and provide easy access, reducing overall At San Benito West Island, 140 artificial wooden nests were disturbance to seabirds (Wilson 1986, Priddel & Carlile 1995) deployed by previous researchers, beginning in 1999, to study the and increasing data-collection efficiency (Wilson 1986). Likewise, breeding biology of Cassin’s Auklet Ptychoramphus aleuticus. restoration programs using artificial nests have improved the Auklets readily accepted and used the nest boxes. In the first year, number of potential nest sites, breeding success (Priddel & Carlile the occupancy rate was 30%, increasing to 80% in the fifth year 1995, De León & Mínguez 2003, Bolton et al. 2004, Bried et al. (Shaye Wolf, pers. comm.). At San Benito, auklets breed earlier 2009, McIver et al. 2016) and adult survival rates (Libois et al. -

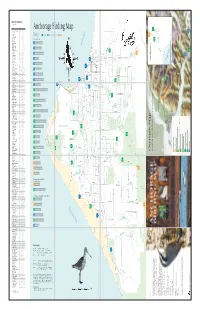

Anchorage Birding Map ❏ Common Redpoll* C C C C ❄ ❏ Hoary Redpoll R ❄ ❏ Pine Siskin* U U U U ❄ Additional References: Anchorage Audubon Society

BIRDS OF ANCHORAGE (Knik River to Portage) SPECIES SP S F W ❏ Greater White-fronted Goose U R ❏ Snow Goose U ❏ Cackling Goose R ? ❏ Canada Goose* C C C ❄ ❏ Trumpeter Swan* U r U ❏ Tundra Swan C U ❏ Gadwall* U R U ❄ ❏ Eurasian Wigeon R ❏ American Wigeon* C C C ❄ ❏ Mallard* C C C C ❄ ❏ Blue-winged Teal r r ❏ Northern Shoveler* C C C ❏ Northern Pintail* C C C r ❄ ❏ Green-winged Teal* C C C ❄ ❏ Canvasback* U U U ❏ Redhead U R R ❄ ❏ Ring-necked Duck* U U U ❄ ❏ Greater Scaup* C C C ❄ ❏ Lesser Scaup* U U U ❄ ❏ Harlequin Duck* R R R ❄ ❏ Surf Scoter R R ❏ White-winged Scoter R U ❏ Black Scoter R ❏ Long-tailed Duck* R R ❏ Bufflehead U U ❄ ❏ Common Goldeneye* C U C U ❄ ❏ Barrow’s Goldeneye* U U U U ❄ ❏ Common Merganser* c R U U ❄ ❏ Red-breasted Merganser u R ❄ ❏ Spruce Grouse* U U U U ❄ ❏ Willow Ptarmigan* C U U c ❄ ❏ Rock Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ White-tailed Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ Red-throated Loon* R R R ❏ Pacific Loon* U U U ❏ Common Loon* U R U ❏ Horned Grebe* U U C ❏ Red-necked Grebe* C C C ❏ Great Blue Heron r r ❄ ❏ Osprey* R r R ❏ Bald Eagle* C U U U ❄ ❏ Northern Harrier* C U U ❏ Sharp-shinned Hawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Northern Goshawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Red-tailed Hawk* U R U ❏ Rough-legged Hawk U R ❏ Golden Eagle* U R U ❄ ❏ American Kestrel* R R ❏ Merlin* U U U R ❄ ❏ Gyrfalcon* R ❄ ❏ Peregrine Falcon R R ❄ ❏ Sandhill Crane* C u U ❏ Black-bellied Plover R R ❏ American Golden-Plover r r ❏ Pacific Golden-Plover r r ❏ Semipalmated Plover* C C C ❏ Killdeer* R R R ❏ Spotted Sandpiper* C C C ❏ Solitary Sandpiper* u U U ❏ Wandering Tattler* u R R ❏ Greater Yellowlegs*