A Vision Plan for Shockoe Bottom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hotel, Travel and Registration Information

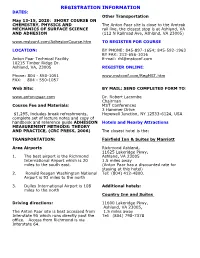

REGISTRATION INFORMATION DATES: Other Transportation May 13-15, 2020: SHORT COURSE ON CHEMISTRY, PHYSICS AND The Anton Paar site is close to the Amtrak MECHANICS OF SURFACE SCIENCE rail line, the closest stop is at Ashland, VA AND ADHESION (112 N Railroad Ave, Ashland, VA 23005) www.mstconf.com/AdhesionCourse.htm TO REGISTER FOR COURSE LOCATION: BY PHONE: 845-897-1654; 845-592-1963 BY FAX: 212-656-1016 Anton Paar Technical Facility E-mail: [email protected] 10215 Timber Ridge Dr. Ashland, VA, 23005 REGISTER ONLINE: Phone: 804 - 550-1051 www.mstconf.com/RegMST.htm FAX: 804 - 550-1057 Web Site: BY MAIL: SEND COMPLETED FORM TO: www.anton-paar.com Dr. Robert Lacombe Chairman Course Fee and Materials: MST Conferences 3 Hammer Drive $1,295, includes break refreshments, Hopewell Junction, NY 12533-6124, USA complete set of lecture notes and copy of handbook and reference guide ADHESION Hotels and Nearby Attractions MEASUREMENT METHODS: THEORY AND PRACTICE, (CRC PRESS, 2006) The closest hotel is the: TRANSPORTATION: Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Area Airports Richmond Ashland, 11625 Lakeridge Pkwy, 1. The best airport is the Richmond Ashland, VA 23005 International Airport which is 20 1.5 miles away miles to the south east. (Anton Paar has a discounted rate for staying at this hotel) 2. Ronald Reagan Washington National Tel: (804) 412-4800. Airport is 93 miles to the north 3. Dulles International Airport is 108 Additional hotels: miles to the north Country Inn and Suites Driving directions: 11600 Lakeridge Pkwy, Ashland, VA 23005, The Anton Paar site is best accessed from 1.5 miles away Interstate 95 which runs directly past the Tel: (804) 798-7378 office. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. VLR Listed: 4/17/2019 NRHP Listed: 5/3/2019 1. Name of Property Historic name: Manchester Trucking and Commercial Historic District Other names/site number: VDHR File #127-6519 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Primarily along Commerce Road, Gordon Ave., and Dinwiddie Ave City or town: Richmond State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic -

Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2016 Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Smith College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Sharron, "Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1477068460. http://doi.org/10.21220/S2D30T This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Renee Smith Richmond, Virginia Master of Liberal Arts, University of Richmond, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, Mary Baldwin College, 1989 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2016 © Copyright by Sharron R. Smith ABSTRACT The Virginia State Constitution of 1869 mandated that public school education be open to both black and white students on a segregated basis. In the city of Richmond, Virginia the public school system indeed offered separate school houses for blacks and whites, but public schools for blacks were conducted in small, overcrowded, poorly equipped and unclean facilities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, public schools for black students in the city of Richmond did not change and would not for many decades. -

For Sale | Shockoe Bottom Office and Multifamily

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR SALE | SHOCKOE BOTTOM OFFICE AND MULTIFAMILY 1707 EAST MAIN STREET Richmond VA 23223 $750,000 PID: E0000109004 Ground and Lower Level Office Space 2 Residential Units on Second Level 4,860 SF Office Space B-5 Central Business Zoning Pulse BRT Corridor Location 0.05 AC Parcel Area Opportunity Zone PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS* 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY 4 PHOTOS 2 8 SHOCKOE BOTTOM NEIGHBORHOOD RESIDENTIAL UNITS 10 PULSE CORRIDOR PLAN 11 RICHMOND METRO AREA 12 RICHMOND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OFFICE 13 RICHMOND MAJOR EMPLOYERS 4,860 SF 14 DEMOGRAPHICS 15 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM B-5 CENTRAL BUSINESS ZONING OPPORTUNITY ZONE 2008 RENOVATION Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of the 1707 E Main St. All communications regarding the property should be directed to the One South Commercial listing team. Property Tours: Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. Disclaimer: This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum. -

Golden Hammer Awards

Golden Hammer Awards 1 WELCOME TO THE 2018 GOLDEN HAMMER AWARDS! Storefront for Community Design and Historic You are focusing on blight and strategically selecting Richmond welcome you to the 2018 Golden Hammer projects to revitalize at risk neighborhoods. You are Awards Ceremony! As fellow Richmond-area addressing the challenges to affordability in new and nonprofits with interests in historic preservation and creative ways. neighborhood revitalization, we are delighted to You are designing to the highest standards of energy co-present these awards to recognize professionals efficiency in search of long term sustainability. You are working in neighborhood revitalization, blight uncovering Richmond’s urban potential. reduction, and historic preservation in the Richmond region. Richmond’s Golden Hammer Awards were started 2000 by the Alliance to Conserve Old Richmond Tonight we celebrate YOU! Neighborhoods. Historic Richmond and Storefront You know that Richmond has much to offer – from for Community Design jointly assumed the Golden the tree-lined streets of its historic residential Hammers in December 2016. neighborhoods to the industrial and commercial We are grateful to you for your commitment to districts whose collections of warehouses are attracting Richmond, its quality of life, its people, and its places. a diverse, creative and technologically-fluent workforce. We are grateful to our sponsors who are playing You see the value in these neighborhoods, buildings, important roles in supporting our organizations and and places. our mission work. Your work is serving as a model for Richmond’s future Thank you for joining us tonight and in our effort to through the rehabilitation of old and the addition of shape a bright future for Richmond! new. -

Virginia ' Shistoricrichmondregi On

VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUPplanner TOUR 1_cover_17gtm.indd 1 10/3/16 9:59 AM Virginia’s Beer Authority and more... CapitalAleHouse.com RichMag_TourGuide_2016.indd 1 10/20/16 9:05 AM VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUP TOURplanner p The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection consists of more than 35,000 works of art. © Richmond Region 2017 Group Tour Planner. This pub- How to use this planner: lication may not be reproduced Table of Contents in whole or part in any form or This guide offers both inspira- by any means without written tion and information to help permission from the publisher. you plan your Group Tour to Publisher is not responsible for Welcome . 2 errors or omissions. The list- the Richmond region. After ings and advertisements in this Getting Here . 3 learning the basics in our publication do not imply any opening sections, gather ideas endorsement by the publisher or Richmond Region Tourism. Tour Planning . 3 from our listings of events, Printed in Richmond, Va., by sample itineraries, attractions Cadmus Communications, a and more. And before you Cenveo company. Published Out-of-the-Ordinary . 4 for Richmond Region Tourism visit, let us know! by Target Communications Inc. Calendar of Events . 8 Icons you may see ... Art Director - Sarah Lockwood Editor Sample Itineraries. 12 - Nicole Cohen G = Group Pricing Available Cover Photo - Jesse Peters Special Thanks = Student Friendly, Student Programs - Segway of Attractions & Entertainment . 20 Richmond ; = Handicapped Accessible To request information about Attractions Map . 38 I = Interactive Programs advertising, or for any ques- tions or comments, please M = Motorcoach Parking contact Richard Malkman, Shopping . -

Shockoe Bottom Shockoe Slip Financial District Capitol Square

Short Pump 5 via I-64West DAVE & BUSTER’S Historic Jackson Ward MAMA J’S 7 City Center VCU Medical BUZ & NED’S RICHMOND ON Center 3 REAL BARBECUE Historic Broad BROAD CAFÉ 12 14 VAGABOND via Broad Street 6 LA GROTTA Street RAPPAHANNOCK 11 10 PASTURE Capitol 13 SPICE OF INDIA Square NOTA BENE 9 Shockoe Bottom CAPITAL ALE Shockoe Slip Historic Monroe Ward HOUSE 4 BOTTOMS UP BOOKBINDERS 1 2 PIZZA Financial District MORTON’S 8 MAP COURTESY VENTURE RICHMOND AND ELEVATION ADVERTISING BOOKBINDER’S SEAFOOD & BOTTOMS UP PIZZA BUZ AND NED’S REAL BARBECUE CAPITAL ALE HOUSE DAVE & BUSTER’S LA GROTTA STEAKHOUSE 1 Shockoe Bottom 2 Boulevard Gateway 3 Financial District 4 Short Pump 5 City Center 6 Shockoe Bottom 1700 Dock Street 1119 N. Boulevard 623 E. Main Street 4001 Brownstone Blvd., 529 E. Broad Street 2306 E. Cary Street 804.644.4400 804.355.6055 804.780.ALES Glen Allen 804.644.2466 804.643.6900 bottomsuppizza.com buzandneds.com capitalalehouse.com 804.967.7399 lagrottaristorante.com bookbindersrichmond.com daveandbusters.com Monday–Wednesday, 11 a.m.–10 p.m. Sunday-Thursday 11 a.m.–9 p.m. Monday–Sunday, 11 a.m.–1:30 a.m. Lunch: Monday–Friday, 11:30 a.m.– Monday–Thursday, 5 p.m.–8:30 p.m. Thursday & Sunday, 11 a.m.–11 p.m. Friday & Saturday 11 a.m.–10 p.m. 2:30 p.m. Friday & Saturday, 11 a.m.–midnight Sunday–Tuesday, 11 a.m.–11 p.m. Dinner: Monday–Thursday, 5 p.m.– Friday & Saturday, 5 p.m.–9 p.m. -

Creighton Phase a 3100 Nine Mile Road Richmond, Virginia 23223

Market Feasibility Analysis Creighton Phase A 3100 Nine Mile Road Richmond, Virginia 23223 Prepared For Ms. Jennifer Schneider The Community Builders, Incorporated 1602 L Street, Suite 401 Washington, D.C., 20036 Authorized User Virginia Housing 601 South Belvidere Street Richmond, Virginia 23220 Effective Date February 4, 2021 Job Reference Number 21-126 JP www.bowennational.com 155 E. Columbus Street, Suite 220 | Pickerington, Ohio 43147 | (614) 833-9300 Market Study Certification NCHMA Certification This certifies that Sidney McCrary, an employee of Bowen National Research, personally made an inspection of the area including competing properties and the proposed site in Richmond, Virginia. Further, the information contained in this report is true and accurate as of February 4, 2021. Bowen National Research is a disinterested third party without any current or future financial interest in the project under consideration. We have received a fee for the preparation of the market study. However, no contingency fees exist between our firm and the client. Virginia Housing Certification I affirm the following: 1. I have made a physical inspection of the site and market area 2. The appropriate information has been used in the comprehensive evaluation of the need and demand for the proposed rental units. 3. To the best of my knowledge the market can support the demand shown in this study. I understand that any misrepresentation in this statement may result in the denial of participation in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program in Virginia as administered by Virginia Housing. 4. Neither I nor anyone at my firm has any interest in the proposed development or a relationship with the ownership entity. -

Shockoe Bottom Memorialization Community and Economic Impacts

SHOCKOE BOTTOM MEMORIALIZATION COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OCTOBER 2019 SHOCKOE BOTTOM MEMORIALIZATION COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS Prepared for: PRESERVATION VIRGINIA SACRED GROUND HISTORICAL RECLAMATION PROJECT NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION Prepared by: CENTER FOR URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS Prepared at: OCTOBER 2019 921 W. Franklin Street • PO Box 842028 • Richmond, Virginia 23284-2028 (804) 828-2274 • www.cura.vcu.edu ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful to Elizabeth Kostelny, Justin Sarafin and Lisa Bergstrom of Preservation Virginia for their leader- ship and support throughout this project. We thank Ana Edwards from the Sacred Ground Historic Reclamation Project and Robert Newman from the National Trust for Historic Preservation for sharing their knowledge with us and providing invaluable insights and feedback. We thank Ana also for many of the images of the Shockoe Bottom area used in this report. We also thank Esra Calvert of the Virginia Tourism Corporation for her assistance in obtaining and local tourism visitation and spending data. And we thank the site/museum directors and repre- sentatives from all case studies for sharing their experiences with us. We are also very grateful to the residents, businesses, community representatives, and city officials who partic- ipated in focus groups, giving their time and insights about this transformative project for the City of Richmond. ABOUT THE WILDER SCHOOL The L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University informs public policy through cutting-edge research and community engagement while preparing students to be tomor- row’s leaders. The Wilder School’s Center for Public Policy conducts research, translates VCU faculty research into policy briefs for state and local leaders, and provides leadership development, education and training for state and local governments, nonprofit organizations and businesses across Virginia and beyond. -

Hermitage Country Club

HERMITAGE COUNTRY CLUB POSITION: GOLF COURSE INTERN Manakin Sabot, VA COURSE CITY ATTRACTIONS The club is situated just outside of Richmond, Virginia, #10 INFORMATION on the list of “18 Cities That Must be Seen in 2018” - Expedia Hermitage Country Club is a 36 (January 2018) and #3 on list of “10 Best Places to Travel in the hole private club formed in 1900. South in 2018” - Southern Living (December 2017). As home to Virginia Commonwealth University (among other colleges) and It is located on the west end of located on the James River, the historic city has no shortage of Richmond, about 30 minutes noteworthy restaurants, bars, and outdoor activities in which to from downtown. The course is indulge when not at the course. situated in a rural area yet services urban clientele. Bentgrass greens, bermudagrass tees, fairways, and roughs summarize the playing surfaces on property. A complete re-grassing was recently finished on the Manakin Course. Cool SHOCKOE BOTTOM SEGWAY TOUR MAYMONT (GARDENS) season turf (save for the greens) was replaced with Latitude36 bermudagrass. The Sabot course is currently undergoing a Bluemuda conversion and a full irrigation system renovation is being planned. VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS BREWERY TOURS Regardless of the student’s previous golf course experience, Hermitage will demand the most possible to secure understanding and an elevated skill set by the internship’s end. We have all the toys to learn CARYTOWN (SHOPPING/DINING) VIRGINIA CAPITAL TRAIL with including the following: a gps sprayer, moisture meters, a drone, an excavator, etc. Please explore the club website as well as the Green Department Blog. -

Richmond Feels the Pressure for Increased Housing Densities

Research & Forecast Report RICHMOND Accelerating success. Q1 2017 | Multifamily Richmond Feels the Pressure for Increased Housing Densities NATIONAL The national investment sale activity showed a sharp decline in more apartments being built downtown and more apartments all real estate sectors in the first quarter of 2017, including the and townhouses being built in the suburbs. Andrew Florance, sale of institutional quality multi-family communities. Per Real Costar founder and CEO, stated recently at a ULI function that Capital Analytics, activity fell 35% YOY, primarily due to the lack Richmond currently has a shortage of nearly 20,000 residential of quality assets coming to the market. The lack of product has units and that there are only six existing units for every ten further stimulated cap rate compression, in turn increasing prices households in need of one. Despite that fact, per Florance, the and providing incentives for owners to reconsider their current Richmond area rental rates and incomes have kept a steady investment horizon. Also, Institutional investors are being drawn pace, unlike that in Primary and Gateway markets. from the Primary and Gateway markets to the Secondary and Tertiary The driving force behind this growth is the Millennial generation, markets in the pursuit of potentially higher yields. Richmond is one the country’s largest generation. Millennials have shown that of the markets benefiting from this action. they are partial to rental housing over ownership and Colliers RICHMOND International predicts that this trend will continue well into the future. Richmond is a prime example. Per Zillow, a Seattle- Richmond is feeling the pressure to increase residential densities based real estate and rental research firm, more Millennials live to accommodate the housing needs for a growing population of alone in Richmond than in any other major U.S. -

Market Analysis Cameo Street Apartments Richmond, Virginia

Market Analysis Cameo Street Apartments Richmond, Virginia Prepared for: Mr. Lee Alford Better Housing Coalition March, 2020 S. Patz and Associates, Inc. 46175 Westlake Drive, Suite 400 Potomac Falls, Virginia 20165 1 March 9, 2020 Mr. Lee Alford Director of Multifamily Real Estate Better Housing Coalition 23 West Broad Street Suite 100 Richmond, Virginia 23220 Lee: This will set forth our full narrative market study for the proposed 67-unit, Cameo Street Apartments, to be built during 2021, for 2022 delivery. The apartment units are to be affordable for a wide range of income groups and will be located in the historic Jackson Ward neighborhood near downtown Richmond, Virginia. The site location is excellent, as it is located within a thriving community with new apartment unit development and within close proximity to employment, community facilities and neighborhood eateries. The 67-unit new construction building will be attractive, with a mix of one-, two- and three-bedroom units, with rents for renters within the 40%, 50% and 60% income categories for the Richmond Region. The Richmond marketplace has supported an abundance of attractive affordable housing and the demand for this type of housing continues, based on net household growth within the income ranges under study, generated by an abundance of new employment growth. The attached Demand Table shows a 2.8 percent required capture rate for market support of the 67 proposed apartment units and a likely five-month lease-up period. All of the detailed market and economic data required for the VHDA market study requirements are included in the attached report.