Social Enterprise Feasibility Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taming the Corporate Beast

This essay was submitted as part of TNI's call for papers for its State of Power 2015 report. The essay was not shortlisted for the final report and therefore TNI does not take responsibility for its contents. However the Editorial Board appreciated the essay and it is posted here as recommended reading. Taming the Corporate Beast An earlier version of this article was published by Dollars and Sense in its July and November 2014 issues. Marianne Hill, Ph.D. The litany of economic disasters in national headlines changes regularly, but a recurring theme is the role of transnational corporations (TNCs) in creating or exacerbating each new calamity. After the 2008 financial crisis, the near nuclear meltdown at Fukushima, the massive BP oil spill, and more, there is global awareness of the dire consequences of tolerating corporate misbehavior and greed. Despite their rhetoric, the priorities of TNCs are fundamentally at odds with the basic social goal of enhancing human freedoms and well-being. It can no longer be denied that the institutional framework regulating global giants requires a thorough transformation. Such a restructuring of our major institutions depends on the liberating knowledge that is being developed through the collective work of agents of change. In this article, I focus on efforts to bring structural changes to corporations that would bring new standpoints to corporate decision- making bodies and, in this way, change the values and control of corporates. I begin with a look at current soul-searching in the business community and efforts that have, at best, beautified the corporate beast. -

Social Enterprises: Examining Accountability for Social and Financial Performance

SOCIAL ENTERPRISES: EXAMINING ACCOUNTABILITY FOR SOCIAL AND FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE Gloria Astrid Guraieb Izaguirre B.A. Financial Management Principal supervisor: Associate Professor Belinda Luke Associate supervisor: Dr Craig Furneaux Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Business (Research) School of Accountancy QUT Business School Queensland University of Technology December 2015 Keywords Accountability, social enterprise, financial, social, performance, non-profit, third sector, Australia Social enterprises: Examining accountability for social and financial performance i Abstract This study explores the accountability of social enterprises with respect to their dual objectives of social and financial performance. During the last two decades, social enterprises have been subject to increasing public attention and research. This interest derives from the potential role of social enterprises to pursue a social mission through a self-funding commercial business model, rather than relying on philanthropy to survive. However, there is little research exploring how social enterprises exercise their accountability for both social and financial performance. Given that social enterprises seek to balance dual objectives, maintaining financial sustainability for long-term survival while also fulfilling their social mission, it is important to examine how these organisations balance accountability for these potentially conflicting goals. There is limited literature on social enterprise accountability, however, as third sector organisations, literature on accountability of non-profit organisations is a useful point of reference. In the context of non-profit organisations, concerns of mission drift and prioritising accountability to donors (as a main funding source) have been raised, where financial objectives may inadvertently override social objectives. Given the social and financial objectives of social enterprises, these issues are also relevant to their accountability. -

Church Hill North, Richmond, VA

Exploring the Health Implications of Mixed-Income Communities January 2019 Mixed-Income Strategic Alliance Church Hill North Richmond, VA Executive Summary approaches to the complex problems of housing quality and stability, concentrated poverty, asset development, This site profi le is part of a series that spotlights food deserts, etc. This profi le also notes the challenges mixed-income community transformations that empha- that arise when the prioritizing and balancing of physical size health and wellness in their strategic interventions. development and human capital development are not The Mixed-Income Strategic Alliance produced these fully in sync. profi les to better understand the health implications of creating thriving and inclusive communities with a socio- The takeaways from this process are, fi rst, the caution to economically and racially diverse population. This site local leaders about the limitations of what can be accom- profi le, which focuses on Creighton Court (and the new plished without federal resources and leadership and the mixed-income community Church Hill North) was de- necessary precondition of consistent local leadership veloped through interviews with local stakeholders and at the City and Housing Authority. Public capacity can’t experts as well as a review of research, publicly-available be replaced with or relegated to civic leaders, despite information, and internal documents. best intentions. In addition, while there are ample efforts targeted to addressing the social determinants of health Creighton Court is a public housing development in in the East End, the importance of balancing physical the East End neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia. To development with the other aspects of mixed-income address the issues surrounding this pocket of racially communities is particularly evident. -

3 Models of Creating Social Impact Through Trading Activities

The 3 Models of Social Enterprise: Creating social impact through trading activities Introduction Within the emerging social investment market, the same words frequently mean different things to different people. In particular, the label “social enterprise” can be especially problematic. In part, this is because there is no shared understanding of the underlying business models beneath the “social enterprise” umbrella. For investors, as the number of organisations labelled as “social enterprises” proliferates, it is becoming increasingly urgent to agree, and then to adopt, a common methodology for disentangling the assessment of financial risk from the likelihood of an investment achieving social returns. Others have already written about ways in which social enterprises may be categorised and described1. We wish to contribute to this ongoing discussion by outlining Venturesome’s current thinking about this issue. This paper introduces a conceptual framework which we hope both investors and investees will find useful as a guide to thinking through how different business models create social impact - and the consequences of this for generating financial returns. The 3 Models Framework We believe that there are three fundamental ways that social impact2 can be created through trading activities: • Model 1 – Engage in a trading activity that has no direct social impact, make a profit, and then transfer some or all of that profit to another activity that does have direct social impact • Model 2 – Engage in a trading activity that does have direct social impact, but manage a trade-off between producing financial return and social impact • Model 3 – Engage in a trading activity that not only has direct social impact, but also generates a financial return in direct correlation to the social impact created It is important to note that these three models are statements of fact, not judgment. -

管 内 発 生 の 重 要 犯 罪 1/1~1/31 アラバマ 中部地区(Area Code 205)

管 内 発 生 の 重 要 犯 罪 1/1~1/31 アラバマ 中部地区(Area Code 205) 場 所 日 付 事 案 名 概 要 ジェフ 1/7/2013 殺人事件 Jefferson County's first slaying Investigators today are searching for clues in the slaying of an Adamsville man ァーソ ン victim of 2013 identified as whose body was discovered Saturday near Maytown. Adamsville man ジェフ 1/9/2013 銃器使用の事 Fairfield police officer shoots at A Fairfield police officer this afternoon shot at two teenagers he said pointed ァーソ 件 ン teens; no one injured a gun at him. No one was injured and the males, ages 18 and 19, are both in custody, said Chief Leon Davis. ジェフ 1/10/2013 殺人事件, 2 shot, 1 stabbed in Gardendale Two people were shot and one stabbed in the 5800 block of Country Meadow Drive ァーソ 傷害事件, ン 銃器使用の事 (updated) in Gardendale, according to Gardendale police this afternoon. 件 ジェフ 1/10/2013 薬物事案 Hunt for wanted Blount County man The search for a wanted man not only turned up the suspect today, but also ァーソ ン turns up suspect and meth lab in turned up a methamphetamine lab in Mt. Olive. Jefferson County ジェフ 1/10/2013 殺人事件, Neighbors say Gardendale house Residents of the Country Meadow Drive neighborhood where two women were shot ァーソ 傷害事件, ン 銃器使用の事 where 2 women shot, 1 man stabbed and a man stabbed today say the house is owned by a pastor of Gardendale-Mt. 件 belonged to Gardendale-Mt. Vernon Vernon United Methodist Church. -

Introduction to Social Enterprise & the Triple Bottom Line the Triple Bottom

Introduction to Social Enterprise & the Triple Bottom Line Drew Tulchin Managing Partner Social Enterprise Associates Webinar for Bankers without Borders Nov 30, 2012 About Social Enterprise Associates Consulting firm ‐ Registered ‘B Corp’ This network of experts offers consulting & capital raising to triple bottom line efforts ‐ for people, profits, planet. Registered ‘B Corporation’ , recognized: 2011 'One of the Best for the World‘ Small Businesses 2012 Honoree, Sustainable Business of the Year Drew Tulchin, Managing Partner, MBA • Former Program Officer, Grameen Foundation • Written >100 business/strategic plans; efforts raised >$100 million • Biz plan winner, Global Social Venture Comp; raised $1.2 mil. in social investment • Judge in international social enterprise & social business competitions Consulting Examples World Food Program: Investigated how to better engage private sector to raise $400 million. Wrote white paper on public‐private partnerships The SEEP Network: Worked with 5 int’l NGOs to develop business plans, hone products, enter new markets, & link to $ in the global North Future of Fish: Capital advisory for social entrepreneurs launching market‐based initiatives that drive sustainability, effic iency, and tbilittraceability in the seafdfood supply chihain. Plan International: Contributed to national studies in W. Africa on economic sector growth opportunities for young adults. Identified growth markets for 50,000 jobs in 3 years SW Native Green Loan Fund: Structured fund to involve small fdifoundations in public‐private -

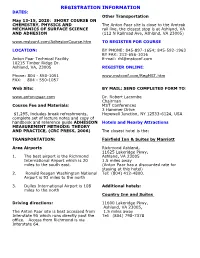

Hotel, Travel and Registration Information

REGISTRATION INFORMATION DATES: Other Transportation May 13-15, 2020: SHORT COURSE ON CHEMISTRY, PHYSICS AND The Anton Paar site is close to the Amtrak MECHANICS OF SURFACE SCIENCE rail line, the closest stop is at Ashland, VA AND ADHESION (112 N Railroad Ave, Ashland, VA 23005) www.mstconf.com/AdhesionCourse.htm TO REGISTER FOR COURSE LOCATION: BY PHONE: 845-897-1654; 845-592-1963 BY FAX: 212-656-1016 Anton Paar Technical Facility E-mail: [email protected] 10215 Timber Ridge Dr. Ashland, VA, 23005 REGISTER ONLINE: Phone: 804 - 550-1051 www.mstconf.com/RegMST.htm FAX: 804 - 550-1057 Web Site: BY MAIL: SEND COMPLETED FORM TO: www.anton-paar.com Dr. Robert Lacombe Chairman Course Fee and Materials: MST Conferences 3 Hammer Drive $1,295, includes break refreshments, Hopewell Junction, NY 12533-6124, USA complete set of lecture notes and copy of handbook and reference guide ADHESION Hotels and Nearby Attractions MEASUREMENT METHODS: THEORY AND PRACTICE, (CRC PRESS, 2006) The closest hotel is the: TRANSPORTATION: Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Area Airports Richmond Ashland, 11625 Lakeridge Pkwy, 1. The best airport is the Richmond Ashland, VA 23005 International Airport which is 20 1.5 miles away miles to the south east. (Anton Paar has a discounted rate for staying at this hotel) 2. Ronald Reagan Washington National Tel: (804) 412-4800. Airport is 93 miles to the north 3. Dulles International Airport is 108 Additional hotels: miles to the north Country Inn and Suites Driving directions: 11600 Lakeridge Pkwy, Ashland, VA 23005, The Anton Paar site is best accessed from 1.5 miles away Interstate 95 which runs directly past the Tel: (804) 798-7378 office. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. VLR Listed: 4/17/2019 NRHP Listed: 5/3/2019 1. Name of Property Historic name: Manchester Trucking and Commercial Historic District Other names/site number: VDHR File #127-6519 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Primarily along Commerce Road, Gordon Ave., and Dinwiddie Ave City or town: Richmond State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic -

Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2016 Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Smith College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Sharron, "Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1477068460. http://doi.org/10.21220/S2D30T This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Renee Smith Richmond, Virginia Master of Liberal Arts, University of Richmond, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, Mary Baldwin College, 1989 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2016 © Copyright by Sharron R. Smith ABSTRACT The Virginia State Constitution of 1869 mandated that public school education be open to both black and white students on a segregated basis. In the city of Richmond, Virginia the public school system indeed offered separate school houses for blacks and whites, but public schools for blacks were conducted in small, overcrowded, poorly equipped and unclean facilities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, public schools for black students in the city of Richmond did not change and would not for many decades. -

Activist Social Entrepreneurship: a Case Study of the Green Campus Co-Operative

Activist Social Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of the Green Campus Co-operative By: Madison Hopper Supervised By: Rod MacRae A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 31 July 2018 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................. 4 FOREWORD........................................................................................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION: WHO’S TO BLAME?.......................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 1: LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................................... 12 SOCIAL ENTERPRISES ............................................................................................................................................... 12 Hybrid Business Models ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Mission Quality - TOMS shoes .......................................................................................................................... -

For Sale | Shockoe Bottom Office and Multifamily

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR SALE | SHOCKOE BOTTOM OFFICE AND MULTIFAMILY 1707 EAST MAIN STREET Richmond VA 23223 $750,000 PID: E0000109004 Ground and Lower Level Office Space 2 Residential Units on Second Level 4,860 SF Office Space B-5 Central Business Zoning Pulse BRT Corridor Location 0.05 AC Parcel Area Opportunity Zone PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS* 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY 4 PHOTOS 2 8 SHOCKOE BOTTOM NEIGHBORHOOD RESIDENTIAL UNITS 10 PULSE CORRIDOR PLAN 11 RICHMOND METRO AREA 12 RICHMOND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OFFICE 13 RICHMOND MAJOR EMPLOYERS 4,860 SF 14 DEMOGRAPHICS 15 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM B-5 CENTRAL BUSINESS ZONING OPPORTUNITY ZONE 2008 RENOVATION Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of the 1707 E Main St. All communications regarding the property should be directed to the One South Commercial listing team. Property Tours: Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. Disclaimer: This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum. -

Enterprise Collaboration & Social Software

Enterprise Collaboration & Social Software June 2013 INDUSTRY REPORT INSIDE THIS ISSUE Enterprise Collaboration & Social Software 1. Introduction INTRODUCTION 2. Market Trends This report focuses on technologies for collaboration and socialization within the enterprise. A number of forces are currently playing out in the enterprise IT 3. Competitive Landscape environment that are creating an inflection in the adoption and deployment of social and collaboration technologies. This significant uptrend has provided strong 4. M&A Activity growth for the sector and is driving a substantial amount of M&A and investment activity. This report includes a review of the recent M&A and private investing 5. Private Financings activities in enterprise social and collaboration software, particularly within the areas of group collaboration & workspaces, private social platforms, project and 6. Valution Trends social task management, event scheduling, web collaboration, white boarding & diagramming, and other related technologies. We have also profiled about 50 emerging private players in these subcategories to provide an overview of the 7. Emerging Private Companies breadth and diversity of the players targeting this sector. OVERVIEW Socialization and collaboration technologies are currently reshaping the established enterprise collaboration market as well as creating whole new categories of offerings, especially around private social platforms. In addition, many other enterprise applications such as CRM and unified communications are heavily transformed through the incorporation of new technologies including group messaging & activity feeds, document collaboration, and analytics. Much of this change is being driven by the consumerization of IT and the incorporation of social technologies. As businesses look to leverage the benefits of improved “connecting” and “network building” that employees have experienced with Facebook and other social solutions, a convergence is occurring between the enterprise social software and collaboration markets.