Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Civil War Differences Between the North and South Geography of The

Differences Between the North and The Civil War South Geography of the North Geography of the South • Climate – frozen winters; hot/humid summers • Climate – mild winters; long, hot, humid summers • Natural features: • Natural features: − coastline: bays and harbors – fishermen, − coastline: swamps and shipbuilding (i.e. Boston) marshes (rice & sugarcane, − inland: rocky soil – farming hard; turned fishing) to trade and crafts (timber for − inland: indigo, tobacco, & shipbuilding) corn − Towns follow rivers inland! Economy of the North Economy of the South • MORE Cities & Factories • Agriculture: Plantations and Slaves • Industrial Revolution: Introduction of the Machine − White Southerners made − products were made cheaper and faster living off the land − shift from skilled crafts people to less skilled − Cotton Kingdom – Eli laborers Whitney − Economy BOOST!!! •cotton made slavery more important •cotton spread west, so slavery increases 1 Transportation of the North Transportation of the South • National Road – better roads; inexpensive way • WATER! Southern rivers made water travel to deliver products easy and cheap (i.e. Mississippi) • Ships & Canals – river travels fast; steamboat • Southern town sprang up along waterways (i.e. Erie Canal) • Railroad – steam-powered machine (fastest transportation and travels across land ) Society of the North – industrial, urban Society of the South – life agrarian, rural life • Maine to Iowa • Black Northerners − free but not equal (i.e. segregation) • Maryland to Florida & west to Texas − worked -

Volume 26 | Number 1 | 2014

Pacific-AsianVolume Education 26 –| Vol.Number 26, No. 1 11 | 2014 Pacific-Asian Education The Journal of the Pacific Circle Consortium for Education Volume 26, Number 1, 2014 ISSUE EDITOR Elizabeth Rata, The University of Auckland EDITOR Elizabeth Rata, School of Critical Studies in Education, Faculty of Education, The University of Auckland, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] EXECUTIVE EDITORS Kirsten Locke, The University of Auckland, New Zealand Elizabeth Rata, The University of Auckland, New Zealand Alexis Siteine, The University of Auckland, New Zealand CONSULTING EDITOR Michael Young, Institute of Education, University of London EDITORIAL BOARD Kerry Kennedy, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong Meesook Kim, Korean Educational Development Institute, South Korea Carol Mutch, Education Review Office, New Zealand Gerald Fry, University of Minnesota, USA Christine Halse, University of Western Sydney, Australia Gary McLean,Texas A & M University, USA Leesa Wheelahan, University of Toronto, Canada Rob Strathdee, RMIT University, Victoria, Australia Xiaoyu Chen, Peking University, P. R. China Saya Shiraishi, The University of Tokyo, Japan Richard Tinning, University of Queensland, Australia Rohit Dhankar, Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India Airini, Thompson Rivers University, British Columbia, Canada ISSN 10109-8725 Pacific Circle Consortium for Education Publication design and layout: Halcyon Design Ltd, www.halcyondesign.co.nz Published by Pacific Circle Consortium for Education http://pacificcircleconsortium.org/PAEJournal.html Pacific-Asian Education Volume 26, Number 1, 2014 CONTENTS Articles The dilemmas and realities of curriculum development: Writing a social studies 5 curriculum for the Republic of Nauru Alexis Siteine Renewal in Samoa: Insights from life skills training 15 David Cooke and T. -

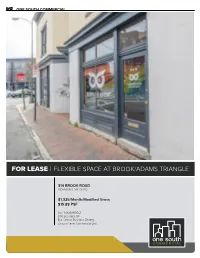

For Lease | Flexible Space at Brook/Adams Triangle

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR LEASE | FLEXIBLE SPACE AT BROOK/ADAMS TRIANGLE 314 BROOK ROAD RICHMOND, VA 23220 $1,325/Month/Modified Gross $19.88 PSF PID: N0000119012 800 Leasable SF B-4 Central Business Zoning Ground Level Commercial Unit PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO Downtown Arts District Storefront A perfect opportunity located right in the heart of the Brook/Adams Road triangle! This beautiful street level retail storefront boasts high ceilings, hardwood floors, exposed brick walls, and an expansive street-facing glass line. With flexible use options, this space could be a photographer studio, a small retail maker space, or the office of a local tech consulting firm. An unquestionable player in the rise of Broad Street’s revitalization efforts underway, this walkable neighborhood synergy includes such residents as Max’s on Broad, Saison, Cite Design, Rosewood Clothing Co., Little Nomad, Nama, and Gallery5. Come be a part of the creative community that is transforming Richmond’s Arts District and meet the RVA market at street level. Highlights Include: • Hardwood Floors • Exposed Brick • Restroom • Janitorial Closet • Basement Storage • Alternate Exterior Entrance ADDRESS | 314 Brook Rd PID | N0000119012 STREET LEVEL BASEMENT STOREFRONT STORAGE ZONING | B-4 Central Business LEASABLE AREA | 800 SF LOCATION | Street Level STORAGE | Basement PRICE | $1,325/Mo/Modified Gross 800 SF HISTORIC LEASABLE SPACE 1912 CONSTRUCTION PRICE | $19.88 PSF *Information provided deemed reliable but not guaranteed 314 BROOK RD | RICHMOND VA 314 BROOK RD | RICHMOND VA DOWNTOWN ARTS DISTRICT AREA FAN DISTRICT JACKSON WARD MONROE PARK 314 BROOK RD VCU MONROE CAMPUS RICHMOND CONVENTION CTR THE JEFFERSON BROAD STREET MONROE WARD RANDOLPH MAIN STREET VCU MED CENTER CARY STREET OREGON HILL CAPITOL SQUARE HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY DOWNTOWN RICHMOND CHURCH HILL ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM ANN SCHWEITZER RILEY [email protected] 804.723.0446 1821 E MAIN STREET | RICHMOND VA ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL 2314 West Main Street | Richmond VA 23220 | onesouthcommercial.com | 804.353.0009 . -

African-American Parents' Experiences in a Predominantly White School

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE June 2017 Opportunity, but at what cost? African-American parents' experiences in a predominantly white school Peter Smith Smith Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Peter Smith, "Opportunity, but at what cost? African-American parents' experiences in a predominantly white school" (2017). Dissertations - ALL. 667. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/667 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract National measures of student achievement, such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), provide evidence of the gap in success between African- American and white students. Despite national calls for increased school accountability and focus on achievement gaps, many African-American children continue to struggle in school academically, as compared to their white peers. Ladson-Billings (2006) argues that a deeper understanding of the legacy of disparity in funding for schools serving primarily African- American students, shutting out African-American parents from civic participation, and unfair treatment of African-Americans despite their contributions to the United States is necessary to complicate the discourse about African-American student performance. The deficit model that uses student snapshots of achievement such as the NAEP and other national assessments to explain the achievement gap suggests that there is something wrong with African-American children. As Cowen Pitre (2104) explains, however, “the deficit model theory blames the victim without acknowledging the unequal educational and social structures that deny African- American students access to a quality education (2014, pg. -

Financing the Schools in Montgomery County, Virginia a Study Conducted by the League of Women Voters of Montgomery County, VA

Financing the Schools in Montgomery County, Virginia A Study Conducted by The League of Women Voters of Montgomery County, VA Introduction The Montgomery County League of Women Voters approved a study of financing for the Montgomery County Public Schools at its annual meeting on May 9, 2018. League members Mary Houska and Wayne “Dempsey” Worner are co-directors of the study. The study addresses the following questions: 1. Is state funding of public education adequate and equitable, and how does it impact funding Montgomery County schools? 2. Has the Montgomery County School Board prepared budgets and has the Board of Supervisors funded budgets that accurately reflect school needs? 3. Are properties in Montgomery County taxed equitably to reflect an appropriate balance of tax revenues from commercial and residential properties? 4. Has the Montgomery County School Board created mechanisms that guarantee equal access to quality programs for all students attending the public schools in the County? The planned completion date for the study was April 2019 for presentation to the League's May 2019 Annual Meeting. Over the summer and fall of 2018: • Meetings were held with representatives of the Montgomery County School Division, the Board of Supervisors, the Commissioner of Revenue’s Office, the Virginia Tech Educational Foundation, and two members of the Virginia General Assembly; • Members of the Montgomery County LWV were invited to join the study group; • Data sources included (1) reports prepared by the Virginia Department of Education; (2) reports prepared by the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis; (3) the Montgomery County Schools Budget and Annual Report documents; (4) the Montgomery County Budget; (5) the Virginia Education Association; (6) Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) reports; and others. -

Creating Safer Routes to School for Fairfield Court Elementary Students

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Master of Urban and Regional Planning Capstone Urban and Regional Studies and Planning Projects 2018 Creating Safer Routes to School for Fairfield ourC t Elementary Students Lara Handwerker Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/murp_capstone Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/murp_capstone/1 This Professional Plan Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban and Regional Studies and Planning at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Urban and Regional Planning Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Creating Safer Routes to School for Fairfield Court Elementary Students Lara McLellan Handwerker Master of Urban and Regional Planning Program L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs Virginia Commonwealth University Spring 2018 Creating Safer Routes to School for Fairfield Court Elementary Students This page intentionally left blank. 2 Creating Safer Routes to School for Fairfield Court Elementary Students Creating Safer Routes to School for Fairfield Court Elementary Students Prepared for: Virginia Department of Transportation Fairfield Court Elementary School Communities in Schools of Richmond Prepared by: Lara McLellan Handwerker Master of Urban and Regional Planning Program L. Douglas Wilder -

Hotel, Travel and Registration Information

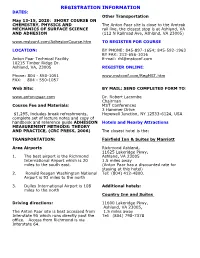

REGISTRATION INFORMATION DATES: Other Transportation May 13-15, 2020: SHORT COURSE ON CHEMISTRY, PHYSICS AND The Anton Paar site is close to the Amtrak MECHANICS OF SURFACE SCIENCE rail line, the closest stop is at Ashland, VA AND ADHESION (112 N Railroad Ave, Ashland, VA 23005) www.mstconf.com/AdhesionCourse.htm TO REGISTER FOR COURSE LOCATION: BY PHONE: 845-897-1654; 845-592-1963 BY FAX: 212-656-1016 Anton Paar Technical Facility E-mail: [email protected] 10215 Timber Ridge Dr. Ashland, VA, 23005 REGISTER ONLINE: Phone: 804 - 550-1051 www.mstconf.com/RegMST.htm FAX: 804 - 550-1057 Web Site: BY MAIL: SEND COMPLETED FORM TO: www.anton-paar.com Dr. Robert Lacombe Chairman Course Fee and Materials: MST Conferences 3 Hammer Drive $1,295, includes break refreshments, Hopewell Junction, NY 12533-6124, USA complete set of lecture notes and copy of handbook and reference guide ADHESION Hotels and Nearby Attractions MEASUREMENT METHODS: THEORY AND PRACTICE, (CRC PRESS, 2006) The closest hotel is the: TRANSPORTATION: Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Area Airports Richmond Ashland, 11625 Lakeridge Pkwy, 1. The best airport is the Richmond Ashland, VA 23005 International Airport which is 20 1.5 miles away miles to the south east. (Anton Paar has a discounted rate for staying at this hotel) 2. Ronald Reagan Washington National Tel: (804) 412-4800. Airport is 93 miles to the north 3. Dulles International Airport is 108 Additional hotels: miles to the north Country Inn and Suites Driving directions: 11600 Lakeridge Pkwy, Ashland, VA 23005, The Anton Paar site is best accessed from 1.5 miles away Interstate 95 which runs directly past the Tel: (804) 798-7378 office. -

Monty Sullivan Vitae- 1

Monty Sullivan Vitae- 1 Monty E. Sullivan, Ed.D. Summary: Proven, innovative higher education leader with over a decade of executive level experience in the community college sector. Education Educational Doctorate Curriculum and Instruction, Louisiana Tech University, Louisiana Educational Consortium (LEC), February 2000 Dissertation entitled Analysis of the Relationship Between Student Course Satisfaction and Student Perception of Interaction in a Compressed Video Setting Master of Education English Education, Louisiana Tech University, May 1994 Bachelor of Arts Political Science, Louisiana Tech University, May 1993 Administrative Experience President- Louisiana Community and Technical College System February 2014 to Present As President, responsible to the Board of Supervisors for state policy and management of board functions for Louisiana’s thirteen community and technical colleges. Developed a bold public agenda, Our Louisiana 2020, which is a six-year plan to build a better Louisiana by significantly boosting the skills, education and earning power of its citizens, and to meet the diverse workforce needs of industry. Nationally recognized for enrollment growth, record number of graduates, substantial increases in giving to the foundations of Louisiana’s community and technical colleges. Chancellor- Delgado Community College June 2012 to February 2014 As Chancellor, responsible for all aspects of leadership and operations of the college and college foundation for the comprehensive community college enrolling over 35,000 students annually with an annual budget of over $90 million. Select accomplishments include: Secured nearly $100 million in bond funding to improve college infrastructure; Raised over $10 million in foundation contributions to support the mission; Graduated the largest class in the college’s 90 year history; Managed through a $13 million deficit; and Reconnected the college with the business community. -

THE CONNERS of WACO: BLACK PROFESSIONALS in TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXAS by VIRGINIA LEE SPURLIN, B.A., M.A

THE CONNERS OF WACO: BLACK PROFESSIONALS IN TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXAS by VIRGINIA LEE SPURLIN, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved ~r·rp~(n oj the Committee li =:::::.., } ,}\ )\ •\ rJ <. I ) Accepted May, 1991 lAd ioi r2 1^^/ hJo 3? Cs-^.S- Copyright Virginia Lee Spurlin, 1991 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is a dream turned into a reality because of the goodness and generosity of the people who aided me in its completion. I am especially grateful to the sister of Jeffie Conner, Vera Malone, and her daughter, Vivienne Mayes, for donating the Conner papers to Baylor University. Kent Keeth, Ellen Brown, William Ming, and Virginia Ming helped me immensely at the Texas Collection at Baylor. I appreciated the assistance given me by Jene Wright at the Waco Public Library. Rowena Keatts, the librarian at Paul Quinn College, deserves my plaudits for having the foresight to preserve copies of the Waco Messenger, a valuable took for historical research about blacks in Waco and McLennan County. The staff members of the Lyndon B. Johnson Library and Texas State Library in Austin along with those at the Prairie View A and M University Library gave me aid, information, and guidance for which I thank them. Kathy Haigood and Fran Thompson expended time in locating records of the McLennan County School District for me. I certainly appreciated their efforts. Much appreciation also goes to Robert H. demons, the county school superintendent. -

Directory of State Authorization Agencies and Lead Contacts October 2017

Directory of State Authorization Agencies and Lead Contacts October 2017 U.S. STATES, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico ALABAMA Alabama Commission on Higher Education Elizabeth C. French Director, Office of Institutional Effectiveness and Planning (334) 242-2179 [email protected] http://www.ache.state.al.us/ Alabama Community College System Tivoli Nash Director of Private School Licensure (334) 293-4653 [email protected] https://www.accs.cc/index.cfm/school-licensure/ Alabama Office of the Secretary of State Elaine Swearengin Division Director (Corp. Records Supervisor) Business Services Division, Alabama State House (334) 242-7221 [email protected] http://sos.alabama.gov/ ALASKA _________________________________________________________________________________ Alaska Commission on Postsecondary Education Kierke A. Kussart Program Coordinator for Institutional Authorization (907) 465-6741 [email protected] [email protected] ARKANSAS Arkansas Department of Higher Education Jeanne Jones Program Specialist, Academic Affairs (501) 371-2039 [email protected] http://www.adhe.edu Arkansas State Board of Private Career Education Alana Boles Program Directory of Private Career and Out-of-State Education (501) 683-8000 [email protected] http://www.sbpce.arkansas.gov/ CALIFORNIA California Bureau for Private Postsecondary Education Joanne Wenzel Bureau Chief (916) 431-6905 [email protected] http://www.bppe.ca.gov/ COLORADO Colorado Department of Higher Education Heather DeLange Academic -

The Perceptions of Race and Identity in Birmingham

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Capstone Collection SIT Graduate Institute Spring 5-25-2014 The eP rceptions of Race and Identity in Birmingham: Does 50 Years Forward Equal Progress? Lisa Murray SIT Graduate Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones Part of the Political History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Murray, Lisa, "The eP rceptions of Race and Identity in Birmingham: Does 50 Years Forward Equal Progress?" (2014). Capstone Collection. 2658. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones/2658 This Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Graduate Institute at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Perceptions of Race and Identity in Birmingham: Does 50 Years Forward Equal Progress? Lisa Jane Murray PIM 72 A Capstone Paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Arts in Conflict Transformation and Peacebuilding at SIT Graduate Institute in Brattleboro, Vermont, USA. May 25, 2014 Advisor: John Ungerleider I hereby grant permission for World Learning to publish my capstone on its websites and in any of its digital/electronic collections, and to reproduce and transmit my CAPSTONE ELECTRONICALLY. I understand that World Learning’s websites and digital collections are publicly available via the Internet. I agree that World Learning is NOT responsible for any unauthorized use of my capstone by any third party who might access it on the Internet or otherwise. -

Richmond, Virginia a Shared Vision for Shockoe Bottom Mission: to Encourage and Support Excellence in Land Use Decision Making

Thanks to the following people for their support in making this panel possible: • The Honorable Levar Stoney, Mayor • City Councilmember Cynthia Newbille • Robert Steidel, Deputy Chief Administrative Officer of Operations • Jane Ferrara, Department of Economic & Community Development • Ellyn Parker, Public Art Coordinator • Jane Milici, Jeffrey Geiger, ULI Virginia Richmond, Virginia A Shared Vision for Shockoe Bottom Mission: To encourage and support excellence in land use decision making. “We should all be open- minded and constantly learning.” --Daniel Rose Mission: Helping city leaders build better communities Mission: Providing leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide Rose Center Programming • Policy & Practice Forums • Education for Public Officials: webinars, workshops, and scholarships to attend ULI conferences Daniel Rose Fellowship • Four cities selected for yearlong program of professional development, leadership training, assistance with a local land use challenge • Mayor selects 3 fellows and project manager alumni cities 2009-2017 class of 2018 cities Salt Lake City Columbus Richmond Tucson Peer Exchange Panel Visit • Assemble experts to study land use challenge • Provides city’s fellowship team with framework and ideas to start addressing their challenge • Part of yearlong engagement with each city The Panel The Panel • Co-Chair: Andre Brumfield, Gensler, Chicago, IL • Co-Chair: Colleen Carey, The Cornerstone Group, Minneapolis, MN • Karen Abrams, The Heinz Endowments, Pittsburgh, PA • Michael Akerlow, Community Development Corporation of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT (Rose Fellow) • Lisa Beyer, Alta Planning + Design, Oakland, CA • Daniel Bursuck, Planning & Development Services Department, City of Tucson, AZ (Rose Fellow) • Christopher Coes, LOCUS: Responsible Real Estate Developers and Investors, Smart Growth America, Washington, DC • Martine Combal, JLL, Washington, DC • Bryan C.