Shockoe Bottom Memorialization Community and Economic Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The African-American Burial Grounds Network Act

The African-American Burial Grounds Network Act Background Cemeteries and burial sites are places of tribute and memory, connecting communities with their past. Unfortunately, many African-American burial grounds from both before and after the Civil War are in a state of disrepair or inaccessibility. Due to Jim Crow-era laws that segregated burial sites by race, many African-American families faced restrictions on where they could bury their dead, and these sites often failed to receive the type of maintenance and record-keeping that predominantly white burial grounds enjoyed. There is no official national record or database for African-American burial ground locations, and the location of many sites is unknown. As a result, the family members and descendants of those interred there are unable to visit these sites to honor and remember their ancestors. Too often, abandoned burial grounds and cemeteries are discovered when construction projects inadvertently disturb human remains, slowing or halting completion of those projects and creating distress and heartache within the local community. The presence and location of historic African-American burial grounds should be chronicled, and there should be coordinated national, state, and local efforts to preserve and restore these sites for future generations. African-American burial grounds are an integral component of the heritage of the United States. Creating and maintaining a network of African-American burial grounds will help communities preserve local history while better informing development decisions and community planning. The African American Burial Grounds Network Act (H.R. 1179) The Adams-McEachin-Budd African-American Burial Grounds Network Act creates a voluntary national network of historic African-American burial grounds. -

Hotel, Travel and Registration Information

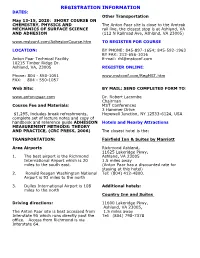

REGISTRATION INFORMATION DATES: Other Transportation May 13-15, 2020: SHORT COURSE ON CHEMISTRY, PHYSICS AND The Anton Paar site is close to the Amtrak MECHANICS OF SURFACE SCIENCE rail line, the closest stop is at Ashland, VA AND ADHESION (112 N Railroad Ave, Ashland, VA 23005) www.mstconf.com/AdhesionCourse.htm TO REGISTER FOR COURSE LOCATION: BY PHONE: 845-897-1654; 845-592-1963 BY FAX: 212-656-1016 Anton Paar Technical Facility E-mail: [email protected] 10215 Timber Ridge Dr. Ashland, VA, 23005 REGISTER ONLINE: Phone: 804 - 550-1051 www.mstconf.com/RegMST.htm FAX: 804 - 550-1057 Web Site: BY MAIL: SEND COMPLETED FORM TO: www.anton-paar.com Dr. Robert Lacombe Chairman Course Fee and Materials: MST Conferences 3 Hammer Drive $1,295, includes break refreshments, Hopewell Junction, NY 12533-6124, USA complete set of lecture notes and copy of handbook and reference guide ADHESION Hotels and Nearby Attractions MEASUREMENT METHODS: THEORY AND PRACTICE, (CRC PRESS, 2006) The closest hotel is the: TRANSPORTATION: Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Area Airports Richmond Ashland, 11625 Lakeridge Pkwy, 1. The best airport is the Richmond Ashland, VA 23005 International Airport which is 20 1.5 miles away miles to the south east. (Anton Paar has a discounted rate for staying at this hotel) 2. Ronald Reagan Washington National Tel: (804) 412-4800. Airport is 93 miles to the north 3. Dulles International Airport is 108 Additional hotels: miles to the north Country Inn and Suites Driving directions: 11600 Lakeridge Pkwy, Ashland, VA 23005, The Anton Paar site is best accessed from 1.5 miles away Interstate 95 which runs directly past the Tel: (804) 798-7378 office. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. VLR Listed: 4/17/2019 NRHP Listed: 5/3/2019 1. Name of Property Historic name: Manchester Trucking and Commercial Historic District Other names/site number: VDHR File #127-6519 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Primarily along Commerce Road, Gordon Ave., and Dinwiddie Ave City or town: Richmond State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic -

Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2016 Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Smith College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Sharron, "Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1477068460. http://doi.org/10.21220/S2D30T This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Renee Smith Richmond, Virginia Master of Liberal Arts, University of Richmond, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, Mary Baldwin College, 1989 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2016 © Copyright by Sharron R. Smith ABSTRACT The Virginia State Constitution of 1869 mandated that public school education be open to both black and white students on a segregated basis. In the city of Richmond, Virginia the public school system indeed offered separate school houses for blacks and whites, but public schools for blacks were conducted in small, overcrowded, poorly equipped and unclean facilities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, public schools for black students in the city of Richmond did not change and would not for many decades. -

2016 FCHC Annual Report

Fairfax County History Commission Annual Report 2016 Fairfax County History Commission Mailing Address: Fairfax County History Commission 10360 North Street Fairfax, Virginia 22030 Telephone: (703) 293-6383 www.fairfaxcounty.gov/histcomm May 1, 2017 Table of Contents Chairman’s Report .................................................................................................. 1 Overview ................................................................................................................... 3 Commemoration of the Founding of Fairfax County .......................................... 4 Fairfax County Resident Curator Program .......................................................... 5 Twelfth Annual History Conference ...................................................................... 6 Awards Programs .................................................................................................... 7 Cultural Resource Management and Protection Branch Grants ....................... 8 Publications ............................................................................................................... 8 Website ...................................................................................................................... 8 Budget........................................................................................................................ 9 Historical Markers ................................................................................................. 10 Ethnic/Oral History .............................................................................................. -

For Sale | Shockoe Bottom Office and Multifamily

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR SALE | SHOCKOE BOTTOM OFFICE AND MULTIFAMILY 1707 EAST MAIN STREET Richmond VA 23223 $750,000 PID: E0000109004 Ground and Lower Level Office Space 2 Residential Units on Second Level 4,860 SF Office Space B-5 Central Business Zoning Pulse BRT Corridor Location 0.05 AC Parcel Area Opportunity Zone PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS* 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY 4 PHOTOS 2 8 SHOCKOE BOTTOM NEIGHBORHOOD RESIDENTIAL UNITS 10 PULSE CORRIDOR PLAN 11 RICHMOND METRO AREA 12 RICHMOND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OFFICE 13 RICHMOND MAJOR EMPLOYERS 4,860 SF 14 DEMOGRAPHICS 15 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM B-5 CENTRAL BUSINESS ZONING OPPORTUNITY ZONE 2008 RENOVATION Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of the 1707 E Main St. All communications regarding the property should be directed to the One South Commercial listing team. Property Tours: Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. Disclaimer: This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum. -

1984 – Present 2018 Summer 2018: Rising Water, Rising Challenges – Elevating Historic Buildings out of Harm’S Way

National Alliance of Preservation Commissions The Alliance Review Index: 1984 – Present 2018 Summer 2018: Rising Water, Rising Challenges – Elevating Historic Buildings Out of Harm’s Way • Resilience in Annapolis – Creating a Cultural Resource Hazard Mitigation Plan – Lisa Craig, Director of Resilience at Michael Baker International • Design Guidelines for Elevating Buildings – The Charleston Process – Dennis J. Dowd, Director of Urban Design and Preservation/City Architect for the City of Charleston • Rising Waters – Raising Historic Buildings – Christopher Wand, AIA • Challenges on the Coast – Flood Mitigation and Historic Buildings – Roderick Scott, Certified Flood Plain Manager, Louisette Scott, Certified Flood Plain Manager and Planning Director in Mandeville, LA • Past Forward 2018 Presentation Conference – Next Stop, San Francisco – Collen Danz, Forum Marketing Manager in the Preservation Division of the National Trust for Historic Preservation • Staff Profile: Joe McGill, Founder, Slave Dwelling Project □ State News o Florida: “Shotgun houses and wood-frame cottages that were once ubiquitous in the historically black neighborhood of West Coconut Grove are fast disappearing under a wave of redevelopment and gentrification.” o North Carolina: “The Waynesville Historic Preservation Commission has made it possible for area fourth graders to have a fun way to get to know their town’s history.” o Oregon: “About half of the residents of Portland’s picturesque Eastmoreland neighborhood want the neighborhood to be designated a historic -

Golden Hammer Awards

Golden Hammer Awards 1 WELCOME TO THE 2018 GOLDEN HAMMER AWARDS! Storefront for Community Design and Historic You are focusing on blight and strategically selecting Richmond welcome you to the 2018 Golden Hammer projects to revitalize at risk neighborhoods. You are Awards Ceremony! As fellow Richmond-area addressing the challenges to affordability in new and nonprofits with interests in historic preservation and creative ways. neighborhood revitalization, we are delighted to You are designing to the highest standards of energy co-present these awards to recognize professionals efficiency in search of long term sustainability. You are working in neighborhood revitalization, blight uncovering Richmond’s urban potential. reduction, and historic preservation in the Richmond region. Richmond’s Golden Hammer Awards were started 2000 by the Alliance to Conserve Old Richmond Tonight we celebrate YOU! Neighborhoods. Historic Richmond and Storefront You know that Richmond has much to offer – from for Community Design jointly assumed the Golden the tree-lined streets of its historic residential Hammers in December 2016. neighborhoods to the industrial and commercial We are grateful to you for your commitment to districts whose collections of warehouses are attracting Richmond, its quality of life, its people, and its places. a diverse, creative and technologically-fluent workforce. We are grateful to our sponsors who are playing You see the value in these neighborhoods, buildings, important roles in supporting our organizations and and places. our mission work. Your work is serving as a model for Richmond’s future Thank you for joining us tonight and in our effort to through the rehabilitation of old and the addition of shape a bright future for Richmond! new. -

Virginia ' Shistoricrichmondregi On

VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUPplanner TOUR 1_cover_17gtm.indd 1 10/3/16 9:59 AM Virginia’s Beer Authority and more... CapitalAleHouse.com RichMag_TourGuide_2016.indd 1 10/20/16 9:05 AM VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUP TOURplanner p The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection consists of more than 35,000 works of art. © Richmond Region 2017 Group Tour Planner. This pub- How to use this planner: lication may not be reproduced Table of Contents in whole or part in any form or This guide offers both inspira- by any means without written tion and information to help permission from the publisher. you plan your Group Tour to Publisher is not responsible for Welcome . 2 errors or omissions. The list- the Richmond region. After ings and advertisements in this Getting Here . 3 learning the basics in our publication do not imply any opening sections, gather ideas endorsement by the publisher or Richmond Region Tourism. Tour Planning . 3 from our listings of events, Printed in Richmond, Va., by sample itineraries, attractions Cadmus Communications, a and more. And before you Cenveo company. Published Out-of-the-Ordinary . 4 for Richmond Region Tourism visit, let us know! by Target Communications Inc. Calendar of Events . 8 Icons you may see ... Art Director - Sarah Lockwood Editor Sample Itineraries. 12 - Nicole Cohen G = Group Pricing Available Cover Photo - Jesse Peters Special Thanks = Student Friendly, Student Programs - Segway of Attractions & Entertainment . 20 Richmond ; = Handicapped Accessible To request information about Attractions Map . 38 I = Interactive Programs advertising, or for any ques- tions or comments, please M = Motorcoach Parking contact Richard Malkman, Shopping . -

Preserving Virginia's Vision of the Past

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 Preserving Virginia's Vision of the Past Karen Merry Reilley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reilley, Karen Merry, "Preserving Virginia's Vision of the Past" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626156. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a8ns-a794 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESERVING VIRGINIA’S VISION OF THE PAST A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Karen M. Reilley 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts W,fi-Ouf Author Approved, July 1998 ^ Kobert Gr0ss Ronald Rosenlqferg Barbara Carson TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract iv Introduction 2 I. Private Preservation of Historic Buildings as National Shrines 4 A. Creating National Shrines 4 B. Virginia’s Leadership in Private Preservation 6 II. Public Preservation Regulation: Historic Districts and Ordinances 10 A. Preservation of Historic Architecture 10 B. Development of Historic Preservation Ordinances 11 III. Implementation of Public Preservation Regulation in Virginia 18 A. -

Preservation Virginia 2012

P RESERVATION V IRGINIA 2012 M OST E NDANG E R E D H ISTORIC S IT E S IN V IRGINIA P RESERVATION V IRGINIA A NNOUNCES 2012 M OST E NDANGERED H ISTORIC S ITES IN V IRGINIA For the eighth consecutive year, Preservation Virginia presents a list of places, buildings and archaeological sites across the Commonwealth that face imminent or sustained threats to their integrity or in some cases their very survival. The list is issued annually to raise awareness of Virginia’s historic sites at risk from neglect, deterioration, lack of maintenance, insufficient funds, inappropriate development or insensitive public policy. The intent is not to shame or punish the current owners of these places. The listing is intended to bring attention to the threats described and to encourage citizens and organizations to continue to advocate for their protection and preservation. In no particular order of severity or significance, these Virginia places are considered as Endangered: LIBBY HILL OVERLOOK, RICHMOND On this spot in 1737, William Byrd II declared that the beautiful view reminded him of Richmond on the Thames in England and named our city Richmond. The sister site in England is a celebrated and protected viewshed. Threat: The viewshed could be lost if proposed high-rise condo units are built along the river which would block this prospect. Libby Hill Overlook Recommendation: Point of Contact: Historic Richmond Foundation and Scenic Virginia are working towards Mrs. Charlotte Kerr positive resolutions. We encourage the use of this designation to support [email protected] a broad coalition of stakeholders to work with the developer and the City of Richmond to find a resolution that preserves this iconic view 804.648.7035 while achieving economic goals. -

Visit the Tusculum Website to View Historic Postcards of the Sweet Briar

July 2010 Volume 1, Issue 4 Director: Lynn Rainville, Ph.D. Annual Teaching with Historic Places Conference a Success In June the Tusculum Institute hosted a conference aimed at teachers and educators, providing them with Tel: 434.381.6432 architectural, historic, and archaeological information E-mail: [email protected] about local history topics. This year's theme was Virginia Indians. Two of our speakers, Karenne Wood (Virginia Foundation for the Humanities) and Victoria Ferguson (Natural Bridge), were from the Monacan Nation and Visit us online: spoke about the history www.tusculum.sbc.edu and cultural traditions of this Piedmont tribe. The state archaeologist, Mike Barber (Department of Historic Resources), gave an overview of several thousand years of Native American artifacts in Virginia. Architectural historian, Marc Wagner (DHR), led the group on a tour of Sweet Briar's historic Ralph Cram-designed buildings and Dee DeRoche (DHR) provided teachers with online resources. Photos from left: Marc Wagner leading a tour of campus; Reproductions of traditional tools used by the Monacans. www.tusculum.sbc.edu/TeachingHistoricPlaces_2010.shtml Please support our restoration of historic DHR Offers Resources for Teaching Indian History in Virginia Tusculum. The Virginia Department of Historic Resources hosts a website with links to resources for teachers. The website also contains an interactive lesson on John White's early 17th-century paintings of Native American life and an historic overview of 17,000 years of their culture in Virginia. Visit the Teachers can also request to borrow a "Native American Tusculum website Archaeological Resources Kit" that contains artifact replicas, maps, books, and videos.