Today's Treasure–Tomorrow's Trust, Virginia's Comprehensive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Form

VLR Listing - 9/6/2006 Vi-/-· 11/1,/1, NRHP Listing - 11/3/2006 ,·~ (-µ{ :.,1(1-i C ' ,ps Form 10·900 0."\18 :\'o. !024-4018 \Ill',·. 10·90) 11. S. Department or the lnh.·:r-ior Town of Bermuda Hundred Historic District ~ational Park Sen'ice Chesterfield Co .. VA '.\TATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This ronn is for use in nomir,ating or requesting d~enninations for individual properties and districts. See instruction.~ in l-lo~vto Complete the National Rcg1sler ofHi~tor1c Places Registration Forrn {National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each Hem by marking "x" in the appropnate box or bycntcnng :he information requcs!cd IC any item does not apply to the property bein~ documented, enter "NIA" for "no: applicable." For functions, architectural ,·las.~ification, nrnteriu!s, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative •terns on con1inuat1011 sheets (NPS Form J 0·900a). Use a t)i)ewflter, word processor, or eompuler, lo complete all items. I. Name of Pro ert ' Historic t<ame: Town ofBennuda Hundred Historic District other names/site number VDHR #020-0064 2. Location street & number_~B~o~t~h~s~id~e~s~o=f~B~e~nn=u~d~•~H=u~n~d~re~d~•n~d~A~l~li~e~d~R~o~a~d~s~______ not for publication ___ _ city or town Chester vicinity_,~X~-- :itate Virginia code VA eounty Chesterfield ____ code 041 Zip _2382 J 3. State/Federal Agency Certification !\s the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, J hereby certify that lhis _x_ nomina11on __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering propenies in the Narional Register ofHmoric Place~ and meets the procedural and professional requirements sel forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Pocahontas State Park

WELCOME TO POCAHONTAS STATE PARK. GUESTS - Your guests are our guests. For everyone’s safety PARK ACCESSIBILITY - We strive to make each park as To make your visit safe and more pleasant, we ask that and security, please register all visitors with the park barrier-free as possible. Universally accessible facilities you observe the following: office. Visitors will not be admitted to camping and are available throughout Virginia State Parks. cabin areas unless so identified. Visitors are permitted EMERGENCY - For medical or fire emergencies dial 9-1-1. For Take only pictures, leave only footprints. Park in only between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m. designated areas only. Please note there is a parking fee other assistance dial 800-933-7275: for law enforcement charged year-round at all Virginia State Parks. Honor QUIET HOURS - Quiet hours are between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. or facility emergencies press 1; to reach the on-duty ranger parking information is found at the park entrance. The use of generators is prohibited at all times. press 2. Pocahontas INFORMATION - For more information on Virginia State PRESERVE – Help preserve your park. Please don’t cut or CHECK-IN AND CHECK-OUT POLICY mar any plants or trees. Collecting animal or plant life is Parks or to make a cabin or campsite reservation, call allowed only for scientific purposes by permit from the Camping: Check-in 4 p.m. Check-out 1 p.m. 800-933-PARK or visit www.virginiastateparks.gov. State Park Cabins and Yurts: Check-in 4 p.m. -

VMI History Fact Sheet

VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE Founded in 1839, Virginia Military Institute is the nation’s first state-supported military college. U.S. News & World Report has ranked VMI among the nation’s top undergraduate public liberal arts colleges since 2001. For 2018, Money magazine ranked VMI 14th among the top 50 small colleges in the country. VMI is part of the state-supported system of higher education in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The governor appoints the Board of Visitors, the Institute’s governing body. The superintendent is the chief executive officer. WWW.VMI.EDU HISTORY OF VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE 540-464-7230 INSTITUTE OFFICERS On Nov. 11, 1839, 23 young Virginians were history. On May 15, 1863, the Corps of mustered into the service of the state and, in Cadets escorted Jackson’s remains to his Superintendent a falling snow, the first cadet sentry – John grave in Lexington. Just before the Battle of Gen. J.H. Binford Peay III B. Strange of Scottsville, Va. – took his post. Chancellorsville, in which he died, Jackson, U.S. Army (retired) Today the duty of walking guard duty is the after surveying the field and seeing so many oldest tradition of the Institute, a tradition VMI men around him in key positions, spoke Deputy Superintendent for experienced by every cadet. the oft-quoted words: “The Institute will be Academics and Dean of Faculty Col. J.T.L. Preston, a lawyer in Lexington heard from today.” Brig. Gen. Robert W. Moreschi and one of the founders of VMI, declared With the outbreak of the war, the Cadet Virginia Militia that the Institute’s unique program would Corps trained recruits for the Confederate Deputy Superintendent for produce “fair specimens of citizen-soldiers,” Army in Richmond. -

Chesterfield County Bikeways and Trails Plan

CHESTERFIELD COUNTY BIKEWAYS AND TRAILS PLAN Draft February 2015 Photo by Jim Waggoner Chesterfield County Planning Department CHAPTER X : BIKEWAYS AND TRAILS PLAN Overview Encouraging a safe and accessible bicycle and pedestrian friendly community is an important part of keeping Chesterfield County an attractive, desirable and healthy place to live, work, shop and recreate. Communities across Virginia and the nation are realizing that biking and walking amenities have a bigger impact than improving the safety of cyclists, walkers and motorists; they are economic development tools that attract new business, provide tourism destinations for visitors and aid in the physical and mental health of their residents. This plan sets the stage to develop a core network of countywide bikeways and trails that address both transportation and recreational needs. Implementation of this plan will provide a safe and comfortable network to walk and bike as viable alternative transportation choices and connect residential areas to destinations such as shopping, services, parks, libraries, jobs and schools. The purpose of this plan is to identify the core network of bikeways and trails, establish design guidelines for the various facility types and recommend policies and ordinances that will develop and enhance this network. This plan supports many of the goals of the Comprehensive Plan including providing a high quality of life for residents and attracting visitors and businesses to our unique environmental, historical and cultural resources. HOW TO USE THIS CHAPTER This plan provides guidelines and recommendations that should be implemented when considering development proposals or public infrastructure projects. The general location of the core network has been identified in this plan, and new rezoning, development plans, and public facility and infrastructure projects should align with this plan by providing facilities to accommodate and enhance the bikeways and trails network. -

From the General History of Virginia John Smith What Happened Till the First Supply

from The General History of Virginia John Smith What Happened Till the First Supply John Smith himself wrote this account of the early months of the Jamestown settlement. For that reason, he may be trying to make his actions seem even braver and more selfless than they were. As you read, stay alert for evidence of exaggerating by Smith. Being thus left to our fortunes, it fortuned1 that within ten days, scarce ten amongst us could either go2 or well stand, such extreme weakness and sickness oppressed us. And thereat none need marvel if they consider the cause and reason, which was this: While the ships stayed, our allowance was somewhat bettered by a daily proportion of biscuit which the sailors would pilfer to sell, give, or exchange with us for money, sassafras,3 or furs. But when they departed, there remained neither tavern, beer house, nor place of relief but the common kettle.4 Had we been as free from all sins as gluttony and drunkenness we might have been canonized for saints, but our President5 would never have been admitted for engrossing to his private,6 oatmeal, sack,7 oil, aqua vitae,8 beef, eggs, or what not but the kettle; that indeed he allowed equally to be distributed, and that was half a pint of wheat and as much barley boiled with water for a man a day, and this, having fried some twenty-six weeks in the ship's hold, contained as many worms as grains so that we might truly call it rather so much bran than corn; our drink was water, our lodgings castles in the air. -

Northern Neck Land Proprietary Records

The Virginia government always held legal jurisdiction over the area owned by the proprietary, so all court actions are found within the records of the counties that comprised it. The Library holds local records such Research Notes Number 23 as deeds, wills, orders, loose papers, and tax records of these counties, and many of these are on microfilm and available for interlibrary loan. Researchers will find that the proprietary records provide a unique doc- umentary supplement to the extant records of this region. The history of Virginia has been enriched by their survival. Northern Neck Land Proprietary Records Introduction The records of the Virginia Land Office are a vital source of information for persons involved in genealog- ical and historical research. Many of these records are discussed in Research Notes Number 20, The Virginia Land Office. Not discussed are the equally rich and important records of the Northern Neck Land Proprietary, also known as the Fairfax Land Proprietary. While these records are now part of the Virginia Land Office, they were for more than a century the archive of a vast private land office owned and oper- ated by the Fairfax family. The lands controlled by the family comprised an area bounded by the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers and stretched from the Chesapeake Bay to what is now West Virginia. It embraced all or part of the cur- rent Virginia counties and cities of Alexandria, Arlington, Augusta, Clarke, Culpeper, Fairfax, Fauquier, Frederick, Greene, King George, Lancaster, Loudoun, Madison, Northumberland, Orange, Page, Prince William, Rappahannock, Shenandoah, Stafford, Warren, Westmoreland, and Winchester, and the current West Virginia counties of Berkeley, Hampshire, Hardy, Jefferson, and Morgan. -

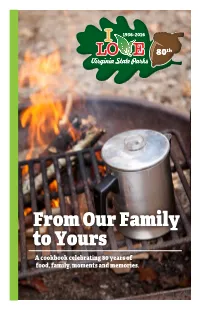

Cookbook.Pdf

From Our Family to Yours A cookbook celebrating 80 years of food, family, moments and memories. Table of Contents Appetizer ............................. 3 Side dish .............................. 8 Main course .......................... 14 Soup and stew ....................... 32 Bread................................. 37 Dessert............................... 40 Beverage ............................. 50 2 • From our family to yours | Table of Contents Crab Canopies Ingredients: “This recipe has been 1 package English muffins passed down from my ½ tsp garlic powder mother to me, and I 2-3 tbsp mayonnaise usually make these only 3 cans crab meat around Thanksgiving and 1-2 jars Kraft Cheez Whiz® Christmas. As children 2-3 tbsp butter growing up in the Midwest, we would prepare them Directions: at every major holiday. Cut each muffin into quarter pieces and then Even though this recipe separate muffin for a total of 8 individual pieces. came from the Midwest, Spread out muffin pieces onto cookie tray. with crab as the main ingredient, it is a regional Mix crab meat, garlic, mayo or butter, and recipe where I live on the cheddar cheese together. Place mixture on Northern Neck of Virginia.” individual muffin pieces. Place wax paper over top of muffin pieces. Place foil on top of wax Alison Weddle paper. (Avoid placing foil directly on top of Assistant Park Manager muffin pieces, as the foil will rip when you Belle Isle State Park try to remove appetizers from pan.) Freeze in freezer for 4-5 hours (or at least until muffins are frozen). Tip: Some people use butter, some use mayo, Broil for 3-4 minutes in oven or toaster oven and some use both. -

2014 Virginia Freshwater Fishing & Watercraft Owner’S Guide

2014 Virginia Freshwater Fishing & Watercraft Owner’s Guide Free Fishing Days: June 6–8, 2014 National Safe Boating Week: May 17–23, 2014 www.HuntFishVA.com Table of Contents Freshwater Fishing What’s New For 2014................................................5 Fishing License Information and Fees ....................................5 Commonwealth of Virginia Freshwater/Saltwater License Lines on Tidal Waters .........................8 Terry McAuliffe, Governor Reciprocal Licenses .................................................8 General Freshwater Fishing Regulations ..................................9 Department of Game Game/Sport Fish Regulations.........................................11 Creel and Length Limit Tables .......................................12 and Inland Fisheries Trout Fishing Guide ................................................18 Bob Duncan, Executive Director 2014 Catchable Trout Stocking Plan...................................20 Members of the Board Special Regulation Trout Waters .....................................22 Curtis D. Colgate, Chairman, Virginia Beach Fish Consumption Advisories .........................................26 Ben Davenport, Vice-Chairman, Chatham Nongame Fish, Reptile, Amphibian, and Aquatic Invertebrate Regulations........27 David Bernhardt, Arlington Let’s Go Fishing Lisa Caruso, Church Road Fish Identification and Fishing Information ...............................29 Charles H. Cunningham, Fairfax Public Lakes Guide .................................................37 Garry L. Gray, -

The African-American Burial Grounds Network Act

The African-American Burial Grounds Network Act Background Cemeteries and burial sites are places of tribute and memory, connecting communities with their past. Unfortunately, many African-American burial grounds from both before and after the Civil War are in a state of disrepair or inaccessibility. Due to Jim Crow-era laws that segregated burial sites by race, many African-American families faced restrictions on where they could bury their dead, and these sites often failed to receive the type of maintenance and record-keeping that predominantly white burial grounds enjoyed. There is no official national record or database for African-American burial ground locations, and the location of many sites is unknown. As a result, the family members and descendants of those interred there are unable to visit these sites to honor and remember their ancestors. Too often, abandoned burial grounds and cemeteries are discovered when construction projects inadvertently disturb human remains, slowing or halting completion of those projects and creating distress and heartache within the local community. The presence and location of historic African-American burial grounds should be chronicled, and there should be coordinated national, state, and local efforts to preserve and restore these sites for future generations. African-American burial grounds are an integral component of the heritage of the United States. Creating and maintaining a network of African-American burial grounds will help communities preserve local history while better informing development decisions and community planning. The African American Burial Grounds Network Act (H.R. 1179) The Adams-McEachin-Budd African-American Burial Grounds Network Act creates a voluntary national network of historic African-American burial grounds. -

Integrating the MAPS Program Into Coordinated Bird Monitoring in the Northeast (U.S

Integrating the MAPS Program into Coordinated Bird Monitoring in the Northeast (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5) A Report Submitted to the Northeast Coordinated Bird Monitoring Partnership and the American Bird Conservancy P.O. Box 249, 4249 Loudoun Avenue, The Plains, Virginia 20198 David F. DeSante, James F. Saracco, Peter Pyle, Danielle R. Kaschube, and Mary K. Chambers The Institute for Bird Populations P.O. Box 1346 Point Reyes Station, CA 94956-1346 Voice: 415-663-2050 Fax: 415-663-9482 www.birdpop.org [email protected] March 31, 2008 i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 3 METHODS ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Collection of MAPS data.................................................................................................................... 5 Considered Species............................................................................................................................. 6 Reproductive Indices, Population Trends, and Adult Apparent Survival .......................................... 6 MAPS Target Species......................................................................................................................... 7 Priority -

The Functions of a Capital City: Williamsburg and Its "Public Times," 1699-1765

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1980 The functions of a capital city: Williamsburg and its "Public Times," 1699-1765 Mary S. Hoffschwelle College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hoffschwelle, Mary S., "The functions of a capital city: Williamsburg and its "Public Times," 1699-1765" (1980). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625107. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ja0j-0893 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FUNCTIONS OF A CAPITAL CITY: »» WILLIAMSBURG AND ITS "PUBLICK T I M E S 1699-1765 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary S„ Hoffschwelle 1980 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Mary S. Hoffschwelle Approved, August 1980 i / S A /] KdJL, C.£PC„ Kevin Kelly Q TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ........................... ................... iv CHAPTER I. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ........................... 2 CHAPTER II. THE URBAN IMPULSE IN COLONIAL VIRGINIA AND ITS IMPLEMENTATION ........................... 14 CHAPTER III. THE CAPITAL ACQUIRES A LIFE OF ITS OWN: PUBLIC TIMES ................... -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia.