Chris Martin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiating Care Across Borders &Generations: an Analysis of Care

Negotiating Care Across Borders & Generations: An Analysis of Care Circulation in Filipino Transnational Families in the Chubu Region of Japan by MCCALLUM Derrace Garfield DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Development GRADUATE SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NAGOYA UNIVERSITY Approved by the Dissertation Committee: ITO Sanae (Chairperson) HIGASHIMURA Takeshi KUSAKA Wataru Approved by the GSID Committee: March 4, 2020 This dissertation is dedication to Mae McCallum; the main source of inspiration in my life. ii Acknowledgements Having arrived at this milestone, I pause to reflect on the journey and all the people and organizations who helped to make it possible. Without them, my dreams might have remained unrealized and this journey would have been dark, lonely and full of misery. For that, I owe them my deepest gratitude. First, I must thank the families who invited me into their lives. They shared with me their most intimate family details, their histories, their hopes, their joys, their sorrows, their challenges, their food and their precious time. The times I spent with the families, both in Japan and in the Philippines, are some of the best experiences I have ever had and I will forever cherish those memories. When I first considered the possibility of studying the family life of Filipinos, I was immediately daunted by the fact that I was a total stranger and an ‘outsider’, even though I had already made many Filipino friends while I was living in Nagano prefecture in Japan. Nevertheless, once I made the decision to proceed and started approaching potential families, my fears were quickly allayed by the warmth and openness of the Filipino people and their willingness to accept me into their lives, their families and their country. -

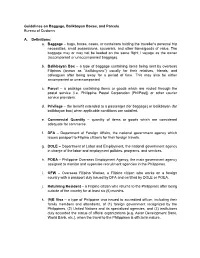

Guidelines on Baggage, Balikbayan Boxes, and Parcels Bureau of Customs

Guidelines on Baggage, Balikbayan Boxes, and Parcels Bureau of Customs A. Definitions: a. Baggage – bags, boxes, cases, or containers holding the traveller’s personal trip necessities, small possessions, souvenirs, and other items/goods of value. The baggage may or may not be loaded on the same flight / voyage as the owner (accompanied or unaccompanied baggage). b. Balikbayan Box – a type of baggage containing items being sent by overseas Filipinos (known as “balikbayans”) usually for their relatives, friends, and colleagues after being away for a period of time. This may also be either accompanied or unaccompanied. c. Parcel – a package containing items or goods which are routed through the postal service (i.e. Philippine Postal Corporation [PhilPost]) or other courier service providers. d. Privilege – the benefit extended to a passenger (for baggage) or balikbayan (for balikbayan box) when applicable conditions are satisfied. e. Commercial Quantity – quantity of items or goods which are considered adequate for commerce. f. DFA – Department of Foreign Affairs, the national government agency which issues passport to Filipino citizens for their foreign travels. g. DOLE – Department of Labor and Employment, the national government agency in charge of the labor and employment policies, programs, and services. h. POEA – Philippine Overseas Employment Agency, the main government agency assigned to monitor and supervise recruitment agencies in the Philippines. i. OFW – Overseas Filipino Worker, a Filipino citizen who works on a foreign country with a passport duly issued by DFA and certified by DOLE or POEA. j. Returning Resident – a Filipino citizen who returns to the Philippines after being outside of the country for at least six (6) months. -

Eileen R. Tabios

POST BLING BLING By Eileen R. Tabios moria -- chicago -- 2005 copyright © 2005 Eileen R. Tabios ISBN: 1411647831 book design by William Allegrezza moria 1151 E. 56th St. #2 Chicago, IL 60637 http://www.moriapoetry.com CONTENTS Page I. POST BLING BLING 1 [Terse-et] 2 WELCOME TO THE LUXURY HYBRID 3 Robert De Niro 4 Infinity Infiniti 5 FOR THE GREATER GOOD 6 THE BEACH IS SERVED 7 “Paloma’s Groove” 8 Be Yourself At Home 9 Your Choice. Your Chase. 10 ESCAPE: Built For The Road Ahead 11 Microsoft Couplet: A Poetics 12 THE DIAMOND TRADING COMPANY—JUST GLITTERING WITH FEMINISM!! 13 W Hotels 14 SWEETHEART 15 YUKON DENALI’S DENIAL II. A LONG DISTANCE LOVE 18 LETTERS FROM THE BALIKBAYAN BOX 40 NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I. POST BLING BLING In a global, capitalistic culture logotypes exist (Nike, McDonalds, Red Cross) which are recognizable by almost all of the planet´s inhabitants. Their meanings and connotations are familiar to more people than any other proper noun of any given language. This phenomenon has caused some artists to reflect on the semiotic content of the words they use, (for example, in the names of perfumes) and isolate them, stripping them down to their pure advertising content. Words are no longer associated with a product, package or price, and go back to their original meaning or to a new one created by the artist. —from Galeria Helga de Alvear's exhibition statement for “Ads, Logos and Videotapes” (Estudio Helga de Alvear), Nov 16 - Jan 13, 2001 [Terse-et] V A N I T Y F A I R V A N I T Y F A R V A N I T Y A I R 1 WELCOME TO THE LUXURY HYBRID It’s not just the debut of a new car, but of a new category. -

Ioften Ask My Students at the Beginning of My Writing

WHERE HAVE ALL OUR MONSTERS GONE?: Using Philippine Lower Mythology in Children’s Literature Carla M. Pacis often ask my students at the beginning of my Writing for Children class who their favorite storybook characters were when Ithey were kids. The answers are usually the same and very predictable – Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Peter Pan et. al. semester upon semester. One day, however, a student from Mindanao said that her favorite characters were the creatures her mother had told her about. These creatures, she said, lived in the forests and mountains that surrounded their town. The whole class and I perked up. What were these creatures, we all wanted to know? She told us of the wak-wak that came out at night to suck the fetus from pregnant sleeping mothers or the tianak that took the form of a cute little baby but was really an ugly dwarf. Ahh, we all nodded, we had also heard of these and many other creatures. Thus ensued an entire session of remembering and recounting of fascinating creatures long forgotten and all our very own. In his book The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim explains the importance of monsters in fairytales and stories. He says that “the monster the child knows best and is most concerned with is the monster he feels or fears himself to be, and which also sometimes, persecutes him. By keeping this monster within the child unspoken of, hidden in his unconscious, adults prevent the child from spinning fantasies around it in the image of the fairytales he knows. -

National City / 619-477-7071

Appete National City / 619-477-7071 Crispy Chicken Wings - Marinated and seasoned, crispy fried chicken wings. Available in Plain, Spicy, Garlic, or Sweet & Spicy. Siomai - Juicy pork dumplings steamed to perfection and served with soy sauce and lemon. Siomai Lumpiang Shanghai - Crispy mini springrolls filled with diced pork, shrimp and spices. Complemented with our signature sweet and sour sauce. Tokwa’t Baboy - Fried tofu mixed with cirspy lechon bits and served with a garlic vingar sauce. Appetizer Sampler - Delicious combination of lumpia shanghai, Lumpia Shanghai chicken empanaditas, and siomai. Calamari - Crispy-friend squid, served with our garlic and vinegar sauce. Soups Bulalo Soup - A hearty beef shank soup with green beans, napa cabbage, potatoes, and sliced carrots. Appetizer Sampler Tinolang Manok - Chicken, chayote, and bok choy simmered in a savory ginger broth. Pork Sinigang - Sour soup made with pork spare ribs and tamarind. Bangus Sinigang - Sour soup made with boneless milkfish and tamarind. Shrimp Sinigang - Sour soup made with shrimp and tamarind. Bulalo Extra shrimp available. Veggie Sinigang - Pork broth with assorted vegetables. Rce Steamed Rice Tinolang Manok Sinangang - Garlic friend rice, a Filipino favorite. Adobo Fried Rice - Fried rice with scrambled egg and diced chicken adobo. Binagoongan Fried Rice - Egg ans rice wok friend with bagoong (shrimp paste). Rice Medley * - Rice topped with mangoes, tomatoes, diced lechon kawali, egg, and drizzled with a special spicy sauce. Rice Medley Adobo or Bagoong fried rice available. Arroz Caldo - Steaming rice porridge with chicken strips topped with green onions and friend garlic. Garlic Fried Rice *We serve Rice Medley with raw eggs on top. -

Philippine Folklore: Engkanto Beliefs

PHILIPPINE FOLKLORE: ENGKANTO BELIEFS HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: Philippine mythology is derived from Philippine folk literature, which is the traditional oral literature of the Filipino people. This refers to a wide range of material due to the ethnic mix of the Philippines. Each unique ethnic group has its own stories and myths to tell. While the oral and thus changeable aspect of folk literature is an important defining characteristic, much of this oral tradition had been written into a print format. University of the Philippines professor, Damiana Eugenio, classified Philippines Folk Literature into three major groups: folk narratives, folk speech, and folk songs. Folk narratives can either be in prose: the myth, the alamat (legend), and the kuwentong bayan (folktale), or in verse, as in the case of the folk epic. Folk speech includes the bugtong (riddle) and the salawikain (proverbs). Folk songs that can be sub-classified into those that tell a story (folk ballads) are a relative rarity in Philippine folk literature.1[1] Before the coming of Christianity, the people of these lands had some kind of religion. For no people however primitive is ever devoid of religion. This religion might have been animism. Like any other religion, this one was a complex of religious phenomena. It consisted of myths, legends, rituals and sacrifices, beliefs in the high gods as well as low; noble concepts and practices as well as degenerate ones; worship and adoration as well as magic and control. But these religious phenomena supplied the early peoples of this land what religion has always meant to supply: satisfaction of their existential needs. -

The Truth of Diwa

The Truth of Diwa Diwa is both the building block and the string upon which all of reality is spun. It permeates all things, and exists in varying states of matter. In a manner of speaking, that chair you see in front of you is Diwa, in a given form. Break it down to its most essential components and you shall see Diwa. However Diwa can be used more than that. It exists in four states: • Agos, Diwa echoing Water. This is the normal state of Diwa, the Diwa that makes up all things. • Tagos, Diwa echoing Air. This is the Diwa that binds things together. It can be manipulated at this level, and if one were to have some means of seeing the invisible machinations of the gods, they will see tiny strands that link everything to everything, as well as the Diwata that embody everything. Diwa in this state can be known as “Fate”, and indeed, the Agents of Heaven call this Tadhana. • Bala, Diwa echoing Fire. This is the Diwa that burns within every living being, and every thing is a living being because everything has a diwata. The Human Eight-Point Soul is made up of this Burning Diwa, and so are the powerful essences of the Karanduun. Burning Diwa can be used to affect other states -- most commonly by having a lot of Burning Diwa, you have more say in how reality works. Thus why Burning Diwa in all beings is known as “Bala”, or “Power”. It is their measure of capability, and it is well known that the Karanduun possess “Unlocked” Bala, which allows their Bala to transcend event that of Gods. -

Crisostomo-Main Menu.Pdf

APPETIZERS Protacio’s Pride 345 Baked New Zealand mussels with garlic and cheese Bagumbayan Lechon 295 Lechon kawali chips with liver sauce and spicy vinegar dip Kinilaw ni Custodio 295 Kinilaw na tuna with gata HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Tinapa ni Tiburcio 200 310 Smoked milkfish with salted egg Caracol Ginataang kuhol with kangkong wrapped in crispy lumpia wrapper Tarsilo Squid al Jillo 310 Sautéed baby squid in olive oil with chili and garlic HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Calamares ni Tales 325 Fried baby squid with garlic mayo dip and sweet chili sauce Mang Pablo 385 Crispy beef tapa Paulita 175 Mangga at singkamas with bagoong Macaraig 255 Bituka ng manok AVAILABLE IN CLASSIC OR SPICY Bolas de Fuego 255 Deep-fried fish and squid balls with garlic vinegar, sweet chili, and fish ball sauce HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Lourdes 275 Deep-fried baby crabs SEASONAL Sinuglaw Tarsilo 335 Kinilaw na tuna with grilled liempo Lucas 375 Chicharon bulaklak at balat ng baboy SIZZLING Joaquin 625 Tender beef bulalo with mushroom gravy Sisig Linares 250 Classic sizzling pork sisig WITH EGG 285 Victoria 450 Setas Salpicao 225 Sizzling salmon belly with sampalok sauce Sizzling button mushroom sautéed in garlic and olive oil KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Carriedo 385 Sautéed shrimp gambas cooked -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Manam-Menu-Compressed.Pdf

Manam prides itself in serving a wide variety of local comfort food. Here, we’ve taken on the challenge of creating edible anthems to Philippine cuisine. At Manam, you can find timeless classic meals side-by-side with their more contemporary renditions, in servings of various sizes. Our meals are tailored to suit the curious palates of this generation’s voracious diners. So make yourself comfortable at our dining tables, and be prepared for the feast we’ve got lined up. Kain na! E n s a la d a a n Classics g Twistsf K am a ti s & Ke son Pica-Pica Pica-Pica g Puti S M L s S M L g in Streetballs of Fish Tofu, Crab, & 145 255 430 Caramelized Patis Wings 165 295 525 R id Lobster with Kalye Sauce u q Pork Ear Kinilaw 150 280 495 gs r S in pe Beef Salpicao & Garlic 180 335 595 W ep is & P k Cheddar & Green Finger 95 165 290 at alt la P chy S k Gambas in Chilis, Olive Oil & Garlic 185 345 615 Chili Lumpia Lu d Crun la m e u p iz B ia l Baby Squid in Olive Oil & Garlic 160 280 485 ng e n Deep-Fried Chorizo & 145 265 520 B m o i a r Kesong Puti Lumpia co r a Crunchy Salt & Pepper Squid Rings 160 280 485 l a h E C c x i p h Lumpiang Bicol Express 75 130 255 r C Tokwa’t Baboy 90 160 275 e s s Fresh Lumpiang Ubod 75 125 230 Chicharon Bulaklak 235 420 830 G isin g G Dinuguan with Puto 170 295 595 is in g Balut with Salt Trio 65 110 170 Ensalada & Gulay Ensalada & Gulay S M L S M L Pinakbet 120 205 365 Adobong Bulaklak ng Kalabasa 120 205 365 Okra, sitaw, eggplant, pumpkin, Pumpkin flowers, fried tofu, tinapa an Ensalad g Namn tomatoes, pork bits, bagoong, -

Research Journal (2019)

Divina M. Edralin Editor-in-Chief San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Nomar M. Alviar Managing Editor San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Ricky C. Salapong Editorial Assistant San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Oscar G. Bulaong, Jr. Ateneo Graduate School of Business, Makati City, Philippines Christian Bryan S. Bustamante San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Li Choy Chong University of St. Gallen, Switzerland Maria Luisa Chua Delayco Asian Institute of Management, Makati City, Philippines Brian C. Gozun De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines Raymund B. Habaradas De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines Ricardo A. Lim Asian Institute of Management, Makati City, Philippines Aloysius Ma. A. Maranan, OSB San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Djonet Santoso University of Bengkulu, Bengkulu, Indonesia Lauro Cipriano S. Silapan, Jr. University of San Carlos, Cebu City, Philippines Marilou Strider Jersey College, School of Nursing, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, U.S.A. From the Editor Divina M. Edralin Editor-in-Chief Research Articles Stewardship Towards God’s Creation Among 1 Early Filipinos: Implications to Faith Inculturation James Loreto C. Piscos Sustainability Repoting of Leading Global 24 Universities in Asia, Europe, and USA Divina M. Edralin and Ronald M. Pastrana The Impact on Life of Estero de San Miguel 46 Noel D. Santander, Josephine C. Dango, and Maria Emperatriz C. Gabatbat Capitalism vs. Creation-Spirituality Resolve (C.S.R.): 72 A Tete-a-tete of Two Cultural Consciousness Jesster B. Fonseca Caring Behaviours, Spiritual, and Cultural Competencies: 98 A Holistic Approach to Nursing Care Gil P. Soriano, Febes Catalina T. Aranas, and Rebecca Salud O. Tejada Restoring the Sanctity and Dignity of Life Among 116 Low-Risk Drug User Surrenderers Neilia B. -

11955 88Th Avenue Delta, BC

PARTY TRAYS Soup SINIGANG NA BABOY $13.95 Lumpiang Shanghai 50 pcs - $40 100 pcs - $75 Pork BBQ (cater size; min. 40 pcs) $2.95/piece Pork belly and mixed vegetables in sour tamarind soup .95 Chicken BBQ (cater size; min. 40 pcs) $2.95/piece SINIGANG NA BANGUS BELLY $14 Embutido $10/piece Boneless milkfish and mixed vegetables in sour tamarind soup Chicken Emapanadas $1.99/piece (min. 25pcs) SINIGANG NA BAKA $15.95 Pritong Lumpia (vegetarian) 25 pcs - $50 Beef short ribs and mixed vegetables in sour tamarind soup Bangus Sisig $12.50/piece (min. 5 pcs) SINIGANG NA CORNED BEEF *NEW* $15.95 Rellenong Bangus $35/piece House-cured corned beef chunks and mixed vegetables SMALL MEDIUM LARGE in sour tamarind soup 13” x 10” x 1.5” 13” x 10” x 2.5” 20.75” x 13” x 2” SINIGANG NA HIPON $15.95 Bicol Express 50 70 130 Shrimp and mixed vegetables in sour tamarind soup Bopis 50 70 130 BULALO $15.95 Cebu Lechon 70 90 160 Beef bone marrow soup with vegetables Crispy Binagoongan 60 80 150 NILAGA $15.95 Dinakdakan 60 80 150 Beef short ribs, potato and baby bokchoy soup Dinuguan 50 70 130 .95 BEEF PAPAITAN *NEW* $14 Lechon Kawali 60 80 150 Beef kamto brisket, tripe and tendon soup Lechon Paksiw 55 75 140 .95 CHICKEN MAMI $8 Menudo 50 70 130 Chicken noodle soup Pork Sisig 60 80 150 BEEF MAMI $10.50 Beef noodle soup Lechon Sisig 70 90 170 LOMI $8.95 Tokwa’t Baboy 55 75 140 Chicken, pork and shrimp in egg drop noodle soup Bistek Tagalog 80 100 180 GOTO $8.95 Kaldereta 70 90 170 Beef tripe and tendon congee Kare Kare 70 90 170 FILIPINO RESTAURANT AND CATERING