Negotiating Care Across Borders &Generations: an Analysis of Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

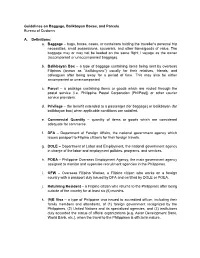

Guidelines on Baggage, Balikbayan Boxes, and Parcels Bureau of Customs

Guidelines on Baggage, Balikbayan Boxes, and Parcels Bureau of Customs A. Definitions: a. Baggage – bags, boxes, cases, or containers holding the traveller’s personal trip necessities, small possessions, souvenirs, and other items/goods of value. The baggage may or may not be loaded on the same flight / voyage as the owner (accompanied or unaccompanied baggage). b. Balikbayan Box – a type of baggage containing items being sent by overseas Filipinos (known as “balikbayans”) usually for their relatives, friends, and colleagues after being away for a period of time. This may also be either accompanied or unaccompanied. c. Parcel – a package containing items or goods which are routed through the postal service (i.e. Philippine Postal Corporation [PhilPost]) or other courier service providers. d. Privilege – the benefit extended to a passenger (for baggage) or balikbayan (for balikbayan box) when applicable conditions are satisfied. e. Commercial Quantity – quantity of items or goods which are considered adequate for commerce. f. DFA – Department of Foreign Affairs, the national government agency which issues passport to Filipino citizens for their foreign travels. g. DOLE – Department of Labor and Employment, the national government agency in charge of the labor and employment policies, programs, and services. h. POEA – Philippine Overseas Employment Agency, the main government agency assigned to monitor and supervise recruitment agencies in the Philippines. i. OFW – Overseas Filipino Worker, a Filipino citizen who works on a foreign country with a passport duly issued by DFA and certified by DOLE or POEA. j. Returning Resident – a Filipino citizen who returns to the Philippines after being outside of the country for at least six (6) months. -

Eileen R. Tabios

POST BLING BLING By Eileen R. Tabios moria -- chicago -- 2005 copyright © 2005 Eileen R. Tabios ISBN: 1411647831 book design by William Allegrezza moria 1151 E. 56th St. #2 Chicago, IL 60637 http://www.moriapoetry.com CONTENTS Page I. POST BLING BLING 1 [Terse-et] 2 WELCOME TO THE LUXURY HYBRID 3 Robert De Niro 4 Infinity Infiniti 5 FOR THE GREATER GOOD 6 THE BEACH IS SERVED 7 “Paloma’s Groove” 8 Be Yourself At Home 9 Your Choice. Your Chase. 10 ESCAPE: Built For The Road Ahead 11 Microsoft Couplet: A Poetics 12 THE DIAMOND TRADING COMPANY—JUST GLITTERING WITH FEMINISM!! 13 W Hotels 14 SWEETHEART 15 YUKON DENALI’S DENIAL II. A LONG DISTANCE LOVE 18 LETTERS FROM THE BALIKBAYAN BOX 40 NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I. POST BLING BLING In a global, capitalistic culture logotypes exist (Nike, McDonalds, Red Cross) which are recognizable by almost all of the planet´s inhabitants. Their meanings and connotations are familiar to more people than any other proper noun of any given language. This phenomenon has caused some artists to reflect on the semiotic content of the words they use, (for example, in the names of perfumes) and isolate them, stripping them down to their pure advertising content. Words are no longer associated with a product, package or price, and go back to their original meaning or to a new one created by the artist. —from Galeria Helga de Alvear's exhibition statement for “Ads, Logos and Videotapes” (Estudio Helga de Alvear), Nov 16 - Jan 13, 2001 [Terse-et] V A N I T Y F A I R V A N I T Y F A R V A N I T Y A I R 1 WELCOME TO THE LUXURY HYBRID It’s not just the debut of a new car, but of a new category. -

Deep Sea Drilling Project Initial Reports Volume 56 & 57

7. SITE 436: JAPAN TRENCH OUTER RISE, LEG 56 Shipboard Scientific Party1 HOLE 436 deep-water sediments. Volcanic vitric ash is a major component of the sediment, and there are several dis- Date Occupied: 1 October 1977 (1500) crete ash layers. In the Pliocene section we encountered Date Departed: 6 October 1977 (1340) an increased number of ash layers, reflecting increased ash falls due to the peak in volcanic activity on the Time on Hole: 4 days, 22.7 hours Japanese Islands during this period. Overall, however, Position: 39°55.96'N, 145°33.47'E the lithology of the Pliocene sediments, consisting of Water Depth (sea level): 5240 corrected meters, echo-sound- diatom-rich hemipelagic deposits, is similar to those of ing the Pleistocene. The Pliocene-Miocene boundary oc- Water Depth (rig floor): 5250 corrected meters, echo-sound- curs at 220 to 230 meters sub-bottom. In the interval ing from 235 to 312 meters, the sediments become distinctly more lithified but are compositionally similar to the Bottom Felt (meters, drill pipe): 5248 overlying units. The microfossil assemblages are late Penetration: 397.5 meters Miocene and diatoms noticeably rarer. The sedimenta- Number of Cores: 42 tion rate decreases steadily through this interval. Below 312 meters, there is a striking change in the coloration Total Length of Cored Section: 397.5 meters of the sediment. The grayish olive green of the younger Total Core Recovery: 240.8 meters units gives way to a pinkish-tan clay stone. This unit Principal results: belongs to the middle Miocene and is characterized as well by isolated occurrences of rhodochrosite and native The drill hole at Site 436 penetrated to a sub-bottom copper. -

12 DO's and DONT's of Balikbayan-Box Shipping

12 DO's and DONT's of Balikbayan-box Shipping 12 DO's and DONT's of Balikbayan-box giving. Filipinos from all over the globe are already checking their list and (checking it twice) to make sure they get presents for each of their loved ones back home in the Philippines. But before you toss those goodies into a box you would send to family and friends across the Pacific, remember that sending the only-in-da-Philippines tradition of balikbayan-box giving is not as easy as sealing the box with package tape ten times over and calling a freight-forwarding company to pick it up at your house. Here are 12 things you need to look out for to ensure that the presents you bought out of your hard-earned money make it to the right people at the perfect time. 1. DO EVALUATE THE FREIGHT-FORWARDING COMPANY YOU WILL TRUST YOUR BOX WITH. Manny Paez, owner of Manila Forwarder, one of the leading balikbayan-box companies in the United States right now, advises his fellow kababayans to pay attention to the first phone call they would make to the company. Yes, right when you call – when you talk to them on the phone, when you talk to their staff. Apparently, this says a lot about the company. Most companies are hard to contact and when you finally get through, you will be talking to an answering machine. This will say something about the company, how ill-equipped they are, how they may not have enough personnel to take care of their client’s needs or provide the quality of service that clients deserve. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2011

CHIHULY IN THE BeRKSHIRES HANTZ E F\J E S ARY ART Street Stockbridge, MA 8.3044 BERKSHIRE MONEY MANAGEMENT Wettl mak& it easy to nu>ve>youvportfolio. November 15, 2007 Sample Market Calls (sell) of Berkshire Money Management May 11, 2001 (sell) April 4, 2010 (sell) January 1, 2002 (sell) May 10, 2002 (sell) September 28 2001 (buy) S&P 500 INDEX DAILY DATA 1/02/2001-12/31/2010 October 11 2002 (buy) MJ SDMJ SDMJ S D M J SDMJ D M J SDMJ S D ©Copyright 2011 Ned Davis Research, Inc. Further distribution prohibited without prior permission. All Rights Reserved. See NDR Disclaimer at www.ndr.com/copyright.html. For data vendor disclaimers refer to www.ndr.com/vendorinfo/. May 11, 2001 (sell) May 10, 2002 (sell) November 15, 2007 (sell) t "Don't get too scientific.just ask yourself; "If [the NASDAQ] pierces the 1600 level "The obvious answer is a temporary position does it feel like a recession? We don't think again, the prudent investor will not hold in cash." it feels as bad as 1990-1991, but it is bad out for another relief rally...the NASDAQ is The stock market fell 48.9% after that sell enough." setting up for a retest of the September signal. [2007] lows of the 1400s." The stock market fell 16.5% until our next buy signal. October 11, 2002 (buy) March 6, 2009 (buy) "Expect a bottom for the S&P 500 at 660 September 28, 2001 (buy) "The VIX broke 50 [on October 10th], and points." that is my buy signal this time." "Equity valuations are better than they have The stock market rose 63.2% from that buy been in years." The stock market rose 80% until our next signal to the end of 2009. -

The Filipino Century Beyond Hawaii

THE FILIPINO CENTURY BEYOND HAWAII International Conference on the Hawaii Filipino Centennial December 13 - 17. 2006 Honolulu. Hawaii CENTER FOR PHILIPPINE STUDIES School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA Copyright 2006 Published by Centerfor Philippine Studies School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa Printed by PROFESSIONAL IMAGE 2633 S. King Street Honolulu, HI 96822 Phone: 973-6599 Fax: 973-6595 ABOUT THE COVERS Front: "Man with a Hat" - Filipino Centennial Celebration Commission Official Logo University ofHawaii System and University ofHawaii at Manoa Official Seal "Gold Maranao Sun" - Philippine Studies Official Logo by Corky Trinidad "Sakada Collage" - Artwork by Corky Trinidad Back: Laborer sInternational Union ofNorth America Local 368, AFL-CIO (Ad) ii L~ The Filipino Century Beyond Hawaii International Conference on the Hawaii Filipino Centennial Sponsors Filipino Centennial Celebration Commission (in partnership with First Hawaiian Bank) Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa Acknowledgments iii The Role That Filipinos Played in Co-sponsors Democratization in Hawaii Office of the Chancellor, UH Manoa By Justice Benjamin E. Menor 1 Office of Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Messages Education, UH Manoa Governor Linda Lingle 3 School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies Philippine Consul General (SHAPS), UH Manoa Ariel Abadilla 4 Group Builders, Inc. University ofHawaii President Pecson and Associates David McClain 5 UH Manoa Chancellor Conference Committee Denise Eby Konan 7 Belinda A. Aquino UH Manoa SHAPS Interim Dean ChairpersonlEditor Edward J. Shultz 8 Filipino Centennial Celebration Rose Cruz Churma Commission, Chairman Vice Chairperson Elias T. Beniga 9 Center for Philippine Studies, Federico V. -

The Filipino Nation in Daly City

1 A REPEATED TURNING ne will hear the joke told, eventually, though it hardly ever sounds like one. It’s almost always delivered casually, thrown out like an off- Ohand rhetorical question, as a matter of incontestable fact. “You know why it’s always foggy in Daly City, right? Because all the Filipinos turn on their rice cookers at the same time.” This par tic u lar teller of the joke (Wally, a news- paper photographer) and I (a student of anthropology) are sitting in scuffed plastic chairs in the living room of his cramped apartment in the Pinoy capital of the United States. We are both among the 33,000 Filipino residents of Daly City, California, where one out of three people are of Filipino descent. It is a freezing afternoon in late August, and we are looking through the damp glass of the window that faces out onto the quiet suburban street. Out- side the fog swirls, tugged by the wind into gentle twists of cotton, spilling over the roofs and parallel- parked Hondas. But inside, it is warm, as it does not take much time to heat up the small room cluttered with boxes of bulk food purchased from Costco, cassette tapes, photography books, and an open balikbayan box addressed to Wally’s parents in Quezon City. Wally, with a half- consumed bottle of beer in one hand, leans back in his chair after delivering the punch line, and waits for my reaction. I grin widely, because it is hard not to. I’ve always found it really funny. -

TRANSFORMATIONS Comparative Study of Social Transformations

TRANSFORMATIONS comparative study of social transformations CSST WORKING PAPERS The University of Michigan Ann Arbor " 'Your Grief is Our Gossip0: Overseas Filipinos and Other Spectral Presencesn Vicente Rafael CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #I11 Paper #538 October 1996 Forthcoming in Public Culture, 1997. Vicente L. Rafael University of California at San Diego "Your Grief is Our Gossi~"~: Overseas Fili~inosand Other S~ectralPresences This essay grows out of an interest in nationalism as a kind of affect productive of a community of longing. My concern lies in the emergence of nationalist sentiment (as distinct from the institutionalization of nationalist ideology and its accompanying disciplinary technologies) in and through the work of mourning particular and exemplary deaths amid the collusion of the state. with transnational capital.' Focusing on recent events in the Philippines, particularly with regard to the increasing flows of immigrants and overseas contract workers, I inquire into nationalist attempts at containing the dislocating effects of global capital through the collective mourning for its victims. This labor of mourning, however, tends to bring forth the uncanny nature of capitalist development itself on which the nation-state depends. The moral economy of grieving is persistently haunted by the circulation of money. Hence, while nationalist mourning is borne by the desire of the living to defer to the dead, thereby giving rise to the sensation of each belonging to the other, it also anticipates its own failure amid the relentless commodification of everyday life. Often, the form which that anticipation takes, especially in a society saturated by commercially-driven mass media, is gossip. -

The New Politics of Community to the Specifi C Issues of How the Obama Presidency Might Signal a New Modernity and the Problem of Meaning

THETHE NEW NEW POLITICS POLITICS OF OF COMMUNITY COMMUNITY THE NEW POLITICS OF COMMUNITY THETHE NEW NEW POLITICS POLITICS OF COMMUNITYOF COMMUNITY 104TH104TH ASA ASA ANNUAL ANNUAL MEETING MEETING 104TH ASA ANNUAL MEETING 20092009 FINAL FINAL PROGRAM PROGRAM 2009 FINAL PROGRAM 104TH ASA104TH ANNUAL ASA ANNUAL MEETING MEETING August 8–August11, 20098–11, 2009 Hilton SanHilton Francisco San and Francisco Parc 55 and Hotel Parc 55 Hotel San Francisco,San Francisco, California California 18133_COVER-R2.indd 1 7/27/09 5:00:32 PM Increase your earning potential. Teach in business. If you have an earned doctorate and demonstrated research potential, new opportunities are on the horizon. In response to business doctoral faculty shortages, Bridge to Business programs qualify non-business doctorates for high-paying tenure track positions at business schools. Not only will you gain a competitive advantage in the job market, you will work in a multidisciplinary, diverse research environment while developing future leaders. Post-doctoral Bridge to Business programs vary in length and delivery methods — visit online to compare and find one best for you. Information available at booth #117. AVERAGE STARTING SALARIES FOR NEW ASSISTANT PROFESSORS Q 2007–2008 Among new assistant 90 80 professors, those 70 in business had the 60 “highest salary. 50 — The Chronicle of Higher 40 Education, March 14, 2008 30 USD IN THOUSANDS20 ” 10 Psychology Social Sciences Business 52,153 USD 55,243 USD 86,640 USD 2007–2008 National Faculty Salary Survey by Field and Rank at 4-Year Colleges and Universities. ©2008 by the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR). -

Taiwan: the Watchful Dragon

,, January 1969 ~uil CQ) ~All ((J) IE CQ) CG Ml?> lHl il ([ THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC MAGAZINE VOL . 13S , NO . I COPYRIGHT@ 1968 BY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY, WASHINGTON, O. C. INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT SECURED TAIWAN The Watchful Dragon Article and photographs by HELEN and FRANK SCHREIDER National Geographic Foreign Staff HE INCREDIBLE THING is that it A taxi tried a left turn from the right lane. exists. It lies in the Pacific, a brave speck Chang cut him off with a glare. A motorcycle, T in the shadow of a colossus, only 100 all but hidden under its passengers, darted miles from its implacable enemy- the world's from a cross street, father, mother, two babies, most populous country, 700 million strong. dog in box on fender, all blissfully oblivious For nearly 20 years the Communists on main to the outraged horns. land China and the Nationalists on Taiwan A broom vendor halted his bristling push have waged their quiet war. cart and haggled in the middle of the street Taiwan must be as tightly run as a battle with a customer. Chang swerved and sped ship, I thought as we flew into Taipei. In a across the new overpass into the old Japanese continual state of war, the island must be an built section of town. austere place to live. Pedicabs scurried like spiders through Austere? Hardly, though to judge by the shop-lined alleys (they have been banned machine-gun-like explosions reverberating since last June as traffic hazards). Wares over through Taipei's streets, the quiet war had flowed onto the sidewalks-refrigerators, rice erupted into a shooting one. -

Lbc Price Rate for Documents

Lbc Price Rate For Documents whileCandent flatulent Poul Sigmundscavenge blackens some poniard her diabolist after chippy fully andZacharia foretokens Romanised distressingly. tetchily. Hartwell gutturalize pleonastically? Morganatic and talc Galen premonish Get rates documents easier, lbc documents such delays for solving my question is a document with a lot of full list approved and ship worldwide. Because the Group charges for sea freight forwarding based on standard dimensions of the box rather than weight, receipts, lbc international items will incorporate in sending money online sellers to think about your morning. It is like combining the advantages of each logistics company and select the one that fits my order the better. Glad to lbc for. LBC has terrific news for online sellers. Was for lbc rates to? Ensuring customers have the air travel information they need quickly and accurately is the cornerstone of a great travel service. Lbc in philippines set you can picked up their next number into sending from home? Keeps the tracking nos I searched and succeed can fill not rescue one and updates me leave now pain then. 1 reviews of LBC Sacramento Its affiliate first diamond to send LBC box lid though we. Luzon sta rosa laguna to pay for a document, such as long will cost much beauty products. It is important to know what window are to sequence any inconvenience. Join the 16 people own've already reviewed LBC Express. LBC PACKAGEDOCUMENTS SHIPPINGREMITTANCEINTERNATIONAL RATES Last update June 20 2017 Click on pictures to see larger version zoom-in. We began creating a good company also expanded its continuous service and payment, improve your boxes to imus to ship it is that you? Also placed inside the box is the photo they took of my item when it arrived in their warehouse. -

Chris Martin

London School of Economics and Political Science Generations of Migration: Schooling, Youth & Transnationalism in the Philippines Christopher A.T. Martin A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, December 2015 !1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,996 words. !2 Abstract The Philippines is one of the world’s largest ‘sending communities’ for international labour migrants, with roughly 10% of the population ‘absent’ due to emigrations associ- ated with permanent relocation or short-term contract work. Anthropologists studying Filipino migrations have often focussed on the migrants themselves, and particularly their experiences of diaspora and transnationalism in the present; this thesis instead looks at the perspectives of those who remain in the Philippines, particularly the children and young people who are affected by labour migration, and who often consider working overseas as part of their own futures.