The Filipino Nation in Daly City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lanao Del Norte – Homosexual – Dimaporo Family – Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: PHL33460 Country: Philippines Date: 2 July 2008 Keywords: Philippines – Manila – Lanao Del Norte – Homosexual – Dimaporo family – Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide references to any recent, reliable overviews on the treatment of homosexual men in the Philippines, in particular Manila. 2. Do any reports mention the situation for homosexual men in Lanao del Norte? 3. Are there any reports or references to the treatment of homosexual Muslim men in the Philippines (Lanao del Norte or Manila, in particular)? 4. Do any reports refer to Maranao attitudes to homosexuals? 5. The Dimaporo family have a profile as Muslims and community leaders, particularly in Mindanao. Do reports suggest that the family’s profile places expectations on all family members? 6. Are there public references to the Dimaporo’s having a political, property or other profile in Manila? 7. Is the Dimaporo family known to harm political opponents in areas outside Mindanao? 8. Do the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) recruit actively in and around Iligan City and/or Manila? Is there any information regarding their attitudes to homosexuals? 9. -

Human Rights Violations on the Basis of Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Homosexuality in the Philippines

Human Rights Violations on the Basis of Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Homosexuality in the Philippines Submitted for consideration at the 106 th Session of the Human Rights Committee for the fourth periodic review of the Philippines October 2012 COALITION REPORT Submitted by: International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) www.IGLHRC.org LGBT AND HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS: INDIVIDUAL LGBT ACTIVISTS: 1. Babaylanes, Inc. 1. Aleksi Gumela 2. Amnesty International Philippines - LGBT Group (AIPh-LGBT) 2. Alvin Cloyd Dakis 3. Bacolod and Negros Gender Identity Society (BANGIS) 3. Arnel Rostom Deiparine 4. Bisdak Pride – Cebu 4. Bemz Benedito 5. Cagayan De Oro Plus (CDO Plus) 5. Carlos Celdran 6. Changing Lane Women’s Group 6. Ian Carandang 7. Coalition for the Liberation of the Reassigned Sex (COLORS) 7. Mae Emmanuel 8. Elite Men’s Circle (EMC) 8. Marion Cabrera 9. EnGendeRights, Inc. 9. Mina Tenorio 10. Filipino Freethinkers (FF) 10. Neil Garcia 11. Fourlez Women’s Group 11. Raymond Alikpala 12. GAYAC (Gay Achievers Club) 12. Ryan Sylverio 13. KABARO-PUP 13. Santy Layno 14. LADLAD Cagayan De Oro 15. LADLAD Caraga, Inc. 16. LADLAD Europa 17. LADLAD LGBT Party 18. LADLAD Region II 19. Lesbian Activism Project Inc. (LeAP!), Inc. 20. Lesbian Piipinas 21. Link Davao 22. Metropolitan Community Church – Metro Baguio City (MCCMB) 23. Miss Maanyag Gay Organization of Butuan 24. OUT Exclusives Women’s Group 25. OUT Philippines LGBT Group 26. Outrage LGBT Magazine 27. Philippine Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches (MCC) 28. Philippine Forum on Sports, Culture, Sexuality and Human Rights (TEAM PILIPINAS) 29. Pink Watch (formerly Philippine LGBT Hate Crime Watch (PLHCW) ) 30. -

Negotiating Care Across Borders &Generations: an Analysis of Care

Negotiating Care Across Borders & Generations: An Analysis of Care Circulation in Filipino Transnational Families in the Chubu Region of Japan by MCCALLUM Derrace Garfield DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Development GRADUATE SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NAGOYA UNIVERSITY Approved by the Dissertation Committee: ITO Sanae (Chairperson) HIGASHIMURA Takeshi KUSAKA Wataru Approved by the GSID Committee: March 4, 2020 This dissertation is dedication to Mae McCallum; the main source of inspiration in my life. ii Acknowledgements Having arrived at this milestone, I pause to reflect on the journey and all the people and organizations who helped to make it possible. Without them, my dreams might have remained unrealized and this journey would have been dark, lonely and full of misery. For that, I owe them my deepest gratitude. First, I must thank the families who invited me into their lives. They shared with me their most intimate family details, their histories, their hopes, their joys, their sorrows, their challenges, their food and their precious time. The times I spent with the families, both in Japan and in the Philippines, are some of the best experiences I have ever had and I will forever cherish those memories. When I first considered the possibility of studying the family life of Filipinos, I was immediately daunted by the fact that I was a total stranger and an ‘outsider’, even though I had already made many Filipino friends while I was living in Nagano prefecture in Japan. Nevertheless, once I made the decision to proceed and started approaching potential families, my fears were quickly allayed by the warmth and openness of the Filipino people and their willingness to accept me into their lives, their families and their country. -

Diaspora Philanthropy: the Philippine Experience

Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience ______________________________________________________________________ Victoria P. Garchitorena President The Ayala Foundation, Inc. May 2007 _________________________________________ Prepared for The Philanthropic Initiative, Inc. and The Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University Supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ____________________________________________ Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience I . The Philippine Diaspora Major Waves of Migration The Philippines is a country with a long and vibrant history of emigration. In 2006 the country celebrated the centennial of the first surge of Filipinos to the United States in the very early 20th Century. Since then, there have been three somewhat distinct waves of migration. The first wave began when sugar workers from the Ilocos Region in Northern Philippines went to work for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association in 1906 and continued through 1929. Even today, an overwhelming majority of the Filipinos in Hawaii are from the Ilocos Region. After a union strike in 1924, many Filipinos were banned in Hawaii and migrant labor shifted to the U.S. mainland (Vera Cruz 1994). Thousands of Filipino farm workers sailed to California and other states. Between 1906 and 1930 there were 120,000 Filipinos working in the United States. The Filipinos were at a great advantage because, as residents of an American colony, they were regarded as U.S. nationals. However, with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which officially proclaimed Philippine independence from U.S. rule, all Filipinos in the United States were reclassified as aliens. The Great Depression of 1929 slowed Filipino migration to the United States, and Filipinos sought jobs in other parts of the world. -

In 1983, the Late Fred Cordova

Larry Dulay Itliong was born in the Pangasinan province of the Philippines on October 25th, 1913. As a young teen, he immigrated to the US in search of work. Itliong soon joined laborers In 1983, the late Fred Cordova (of the Filipino American National Historical Society) wrote a working everywhere from Washington to California to Alaska, organizing unions and labor strikes book called Filipinos: Forgotten Asian Americans, a pictorial essay documenting the history of as he went. He was one of the manongs, Filipino bachelors in laborer jobs who followed the Filipinos in America from 1763 to 1963. He used the word “forgotten” to highlight that harvest. Filipino Americans were invisible in American history books during that time. Despite lacking a formal secondary education, Itliong spoke multiple languages and taught himself about law by attending trials. In 1965, he led a thousand Filipino farm workers to strike Though Filipino Americans were the first Asian Americans to arrive in the U.S. in 1587 (33 against unfair labor practices in Delano, CA. His leadership in Filipino farm worker movement years before the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock in 1620), little was written about the history paved the way for others to follow. Alongside Cesar Chavez, Larry Itliong founded the United of the Philippines or of Filipino Americans in the U.S. Although the U.S. has a long history with Farm Workers Union. Together, they built an unprecedented coalition between Filipino and the Philippines (including the Philippine-American War, American colonization from 1899-1946, Mexican laborers and connected their strike to the concurrent Civil Rights Movement. -

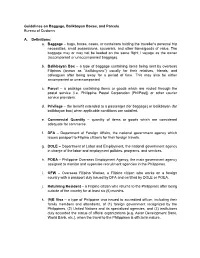

Guidelines on Baggage, Balikbayan Boxes, and Parcels Bureau of Customs

Guidelines on Baggage, Balikbayan Boxes, and Parcels Bureau of Customs A. Definitions: a. Baggage – bags, boxes, cases, or containers holding the traveller’s personal trip necessities, small possessions, souvenirs, and other items/goods of value. The baggage may or may not be loaded on the same flight / voyage as the owner (accompanied or unaccompanied baggage). b. Balikbayan Box – a type of baggage containing items being sent by overseas Filipinos (known as “balikbayans”) usually for their relatives, friends, and colleagues after being away for a period of time. This may also be either accompanied or unaccompanied. c. Parcel – a package containing items or goods which are routed through the postal service (i.e. Philippine Postal Corporation [PhilPost]) or other courier service providers. d. Privilege – the benefit extended to a passenger (for baggage) or balikbayan (for balikbayan box) when applicable conditions are satisfied. e. Commercial Quantity – quantity of items or goods which are considered adequate for commerce. f. DFA – Department of Foreign Affairs, the national government agency which issues passport to Filipino citizens for their foreign travels. g. DOLE – Department of Labor and Employment, the national government agency in charge of the labor and employment policies, programs, and services. h. POEA – Philippine Overseas Employment Agency, the main government agency assigned to monitor and supervise recruitment agencies in the Philippines. i. OFW – Overseas Filipino Worker, a Filipino citizen who works on a foreign country with a passport duly issued by DFA and certified by DOLE or POEA. j. Returning Resident – a Filipino citizen who returns to the Philippines after being outside of the country for at least six (6) months. -

Eileen R. Tabios

POST BLING BLING By Eileen R. Tabios moria -- chicago -- 2005 copyright © 2005 Eileen R. Tabios ISBN: 1411647831 book design by William Allegrezza moria 1151 E. 56th St. #2 Chicago, IL 60637 http://www.moriapoetry.com CONTENTS Page I. POST BLING BLING 1 [Terse-et] 2 WELCOME TO THE LUXURY HYBRID 3 Robert De Niro 4 Infinity Infiniti 5 FOR THE GREATER GOOD 6 THE BEACH IS SERVED 7 “Paloma’s Groove” 8 Be Yourself At Home 9 Your Choice. Your Chase. 10 ESCAPE: Built For The Road Ahead 11 Microsoft Couplet: A Poetics 12 THE DIAMOND TRADING COMPANY—JUST GLITTERING WITH FEMINISM!! 13 W Hotels 14 SWEETHEART 15 YUKON DENALI’S DENIAL II. A LONG DISTANCE LOVE 18 LETTERS FROM THE BALIKBAYAN BOX 40 NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I. POST BLING BLING In a global, capitalistic culture logotypes exist (Nike, McDonalds, Red Cross) which are recognizable by almost all of the planet´s inhabitants. Their meanings and connotations are familiar to more people than any other proper noun of any given language. This phenomenon has caused some artists to reflect on the semiotic content of the words they use, (for example, in the names of perfumes) and isolate them, stripping them down to their pure advertising content. Words are no longer associated with a product, package or price, and go back to their original meaning or to a new one created by the artist. —from Galeria Helga de Alvear's exhibition statement for “Ads, Logos and Videotapes” (Estudio Helga de Alvear), Nov 16 - Jan 13, 2001 [Terse-et] V A N I T Y F A I R V A N I T Y F A R V A N I T Y A I R 1 WELCOME TO THE LUXURY HYBRID It’s not just the debut of a new car, but of a new category. -

BATANGAS Business Name Batangas Egg Producers Cooperative (BEPCO) Owner Board Chairman: Ms

CALABARZON MSMEs featured in Pasa-Love episode (FOOD) BATANGAS Business Name Batangas Egg Producers Cooperative (BEPCO) Owner Board Chairman: Ms. Victorino Michael Lescano Representative: Ms. Judit Alday Mangmang Business Address San Jose, Batangas Mobile/Telephone Number 0917 514 5790 One-paragraph Background Main Product/s: Pasteurized and Cultured Egg BEPCO is a group which aspires to help the egg industry, especially in the modernization and uplift of agriculture. BEPCO hopes to achieve a hundred percent utilization of eggs and chicken. Therefore, BEPCO explores on ways to add value to its products which leads to the development of pasteurized eggs, eggs in a bottle (whole egg, egg yolk and egg white), and Korean egg, which used South Korea’s technology in egg preservation. Website/Social Media Links Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Batangas- Egg-Producers-Cooperative-137605103075662 Website: https://batangasegg.webs.com/ Business Name Magpantay Homemade Candy Owner Ms. Carmela Magpantay Business Address Lipa City, Batangas Mobile/Telephone Number 0915 517 1349 One-paragraph Background Main Product/s: Mazapan, Yema, Pastillas (Candies and Sweets) JoyVonCarl started as a family business which aimed to increase the family income. During the time, Carmela Magpantay was still employed as a factory worker who eventually resigned and focused on the business venture. Now, JoyVonCarl is flourishing its business and caters to candy lovers across the country. Website/Social Media Links Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mimay.magpantay.39 Business Name Mira’s Turmeric Products Owner Ms. Almira Silva Business Address Lipa City, Batangas Mobile/Telephone Number 0905 4060102 One-paragraph Background Main Product/s: Turmeric and Ginger Tea Mira’s started when the owner attended on various agricultural trainings and honed her advocacy in creating a product which would help the community. -

Filipino 11.2

Ateneo De Manila University Loyola Schools FILIPINO 11.2 School of Humanities KAGAWARAN NG FILIPINO Filipino for Foreign Students: (Department of Filipino) Introduction to Philippine Culture through Immersion Second Semester, SY 2016-2017 ( Spring Term 2017) | 3 units | Mr. Jomar I. Empaynado COURSE SYLLABUS LEARNING OUTCOMES At the end of the course, the students should be able to demonstrate a holistic understanding of Philippine society and culture as complemented by their competency in the following language skills and communication situations: 1. SPEAKING: a. Express self clearly, effectively, and confidently through utterances of basic expressions, patterned responses, and simple sentences in Filipino in specific situations such as: introducing self and others, exchanging greetings, asking basic information, answering simple questions, telling time, and buying or requesting for something. This can be measured through classroom discussions, dialogues, short skits/role play, interviews and conversing with the locals, as well as in the presentations of the interviews and sharing of experiences. 2. LISTENING: a. Understand and respond to sentence-length utterances given in specific contexts such as sharing information about self, reacting to spoken expressions which reveal emotions, and following simple instructions. b. Recognize the meaning of a spoken Filipino word/expression as guided by an applied stress and intonation. Within classroom setting, these can be measured through ‘Bul-ul’ Ifugao’s Rice God discussions and recitations, dialogues/short skits/role play, and other oral exercises which involve listening to music, (Standing ‘Bul-ul’: Rice God Figure) watching video clips, and films, etc. Within community http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/219.2005/ settings, these can be measured through conversing with the locals and doing interviews on field trips which the students need to report/present/share during classroom discussions. -

How Filipino Food Is Becoming the Next Great American Cuisine.” by Ty Matejowsky, University of Central Florida

Volume 16, Number 2 (2020) Downloaded from from Downloaded https://www.usfca.edu/journal/asia-pacific-perspectives/v16n2/matejowsky PHOTO ESSAY: Contemporary Filipino Foodways: Views from the Street, Household, and Local Dining, “How Filipino Food is Becoming the Next Great American Cuisine.” By Ty Matejowsky, University of Central Florida Abstract As a rich mélange of outside culinary influences variously integrated within the enduring fabric of indigenous food culture, contemporary Filipino foodways exhibit an overarching character that is at once decidedly idiosyncratic and yet uncannily familiar to those non- Filipinos either visiting the islands for the first time or vicariously experiencing its meal/ snack offerings through today’s all but omnipresent digital technology. Food spaces in the Philippines incorporate a wide range of venues and activities that increasingly transcend social class and public/domestic contexts as the photos in this essay showcase in profound and subtle ways. The pictures contained herein reveal as much about globalization’s multiscalar impact as they do Filipinos’ longstanding ability to adapt and assimilate externalities into more traditional modes of dietary practice. Keywords: Philippines, foodways, globalization Asia Pacific Perspectives Contemporary Filipino Foodways - Ty Matejowsky • 67 Volume 16, No. 2 (2020) For various historical and geopolitical reasons, the Philippines remains largely distinct in the Asia Pacific and, indeed, around the world when it comes to the uniqueness of its culinary heritage and the practices and traditions surrounding local food production and consumption. While the cuisines of neighboring countries (e.g. Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and China) have enjoyed an elevated status on the global stage for quite some time, Filipino cooking and its attendant foodways has pretty much gone under the radar relatively speaking Figure 1. -

Jeremaiah Opiniano

THE DYNAMICS OF TRANSNATIONAL PHILANTHROPY BY MIGRANT WORKERS TO THEIR COMMUNITIES OF ORIGIN: THE CASE OF POZORRUBIO, PHILIPPINES by JEREMAIAH M. OPINIANO Institute on Church and Social Issues Manila, Philippines Paper presented to the Fifth International Society for Third-Sector Research (ISTR) International Conference July 10, 2002 – University of Cape Town, South Africa THE Philippine government heralds its over seven million citizens overseas, popularly known as overseas Filipino workers (OFWs), as the country’s “modern-day heroes.” The remittances that these Filipino migrants1 send, which amount to over US$ 6 billion from 1999 to 2001, have helped save the struggling Philippine economy. Remittances’ economic contributions are a significant reason why the government continues to make international labor migration a vital part of the country’s economic recovery efforts. For nearly three decades, international labor migration has helped the Philippines ease high unemployment rates, improve its balance of payments, and increase foreign reserves. There has been much debate on how remittances should be spent, and how are they “productively” or “unproductively” used. But one of the identified approaches of how migrants utilize remittances, aside from doing this for the consumptive needs of their families, is financing social and economic development projects in the emigration country. An example is Senegal, where remittances from international migrants are a source of revenue for both migrant families and the social development projects of the hometowns (Ammassari and Black, 2001). This practice is what civil society scholars call diaspora philanthropy, although the author is renaming this as transnational philanthropy (with supplementary theoretical and conceptual explanations). For civil society studies, philanthropy from the diaspora is a newly emerging theme. -

Asian Americans

A SNAPSHOT OF BEHAVI ORAL HEALTH ISSUES FOR AS IAN AMERICAN/ NATIVE HAWAIIAN/PACIFIC ISLANDER BOYS AND MEN: JUMPSTARTING AN OVERDUE CONVERSATION PURPOSE OF THE BRIEF address these issues need to be documented. Recognizing that this brief is not a comprehensive, As part of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health in-depth discussion of all the pertinent behavioral Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) efforts to health issues for each AANHPI subgroup, this brief promote behavioral health equity and to support represents a start to a much overdue conversation and President Obama’s “My Brother’s Keeper” Initiative action strategy. to address opportunity gaps for boys and young men of color, SAMHSA and the American Psychological WHO IS THIS BRIEF FOR? Association co-sponsored the “Pathways to Behavioral Health Equity: Addressing Disparities The primary audiences for this brief are policy Experienced by Men and Boys of Color” conference makers, clinicians and practitioners, researchers, in March 2015. The purpose of the conference was to national/regional and state leaders, community address the knowledge gap on behavioral health and leaders and consumers, and men and boys of color overall well-being for boys and young men of color. and their families and communities. Issues discussed included (a) gender and identity, (b) social determinants of health and well-being, (c) mental health, substance use, and sexual health, (d) WHO ARE ASIAN AMERICANS, misdiagnosis, treatment bias, and the lack of NATIVE HAWAIIANS, AND culturally competent screening instruments and PACIFIC ISLANDERS? treatment strategies in behavioral health, (d) the impact of profiling and stereotypes on behavior, and The AANHPI population consists of over 50 distinct (e) unique culturally based strategies and programs.