Research Journal (2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Original Article

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2018 Volume 11 | Issue 2| Page 697 Original Article Caring Behavior and Patient Satisfaction: Merging for Satisfaction Kathyrine A. Calong Calong School of Dentistry, Centro Escolar University, Manila, Philippines Gil P. Soriano, MHPEd, RN Assistant Professor, College of Nursing, San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Correspondence: Gil P. Soriano, MHPEd, RN, Assistant Professor, College of Nursing, San Beda University, Manila, Philippines E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract Background: Caring is considered as the fundamental concept of nursing role and provides framework to guide the nursing practice. It involves viewing the totality of an individual in order to provide an optimal level of care to patients. However, this has become a challenge in the current health care system due to the advancement of technology coupled by scarce resources, shortage of nursing personnel and occupational stress. Objectives: The purpose of this descriptive-correlational study was to determine the level of caring behaviors of nurses as perceived by the nurses and patients and determine the difference between their perceptions. Furthermore, the relationship between the level of caring behavior and patient’s satisfaction was determined. Methodology: A purposive sample of 101 patients and 47 nurses were selected in medical-surgical unit of selected Level 3 Hospitals in Manila, Philippines. Staff nurses and patients were asked to rate the level of caring behavior using the Clinical Nurse Patient Interaction Scale (CNPI) Also, patients were asked to rate their level of satisfaction using the Patient Satisfaction Instrument (PSI). Results: Finding suggests that nurses rated themselves higher in terms of caring behavior as compared to the ratings of the patients. -

Ioften Ask My Students at the Beginning of My Writing

WHERE HAVE ALL OUR MONSTERS GONE?: Using Philippine Lower Mythology in Children’s Literature Carla M. Pacis often ask my students at the beginning of my Writing for Children class who their favorite storybook characters were when Ithey were kids. The answers are usually the same and very predictable – Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Peter Pan et. al. semester upon semester. One day, however, a student from Mindanao said that her favorite characters were the creatures her mother had told her about. These creatures, she said, lived in the forests and mountains that surrounded their town. The whole class and I perked up. What were these creatures, we all wanted to know? She told us of the wak-wak that came out at night to suck the fetus from pregnant sleeping mothers or the tianak that took the form of a cute little baby but was really an ugly dwarf. Ahh, we all nodded, we had also heard of these and many other creatures. Thus ensued an entire session of remembering and recounting of fascinating creatures long forgotten and all our very own. In his book The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim explains the importance of monsters in fairytales and stories. He says that “the monster the child knows best and is most concerned with is the monster he feels or fears himself to be, and which also sometimes, persecutes him. By keeping this monster within the child unspoken of, hidden in his unconscious, adults prevent the child from spinning fantasies around it in the image of the fairytales he knows. -

ACADEMIC CALENDAR SCHOOL YEAR 2019-2020 First Semester

ACADEMIC CALENDAR SCHOOL YEAR 2019-2020 First Semester: June 3, 2019 - October 5, 2019 June 3, Monday Classes Begin June 5, Wednesday Holiday (Eid-Ul-Fitr) June 12, Wednesday Holiday (Independence Day) July 8-13, Monday-Saturday Preliminary Examinations August 12, Monday Holiday (Eid-Ul-Adha) August 19-20, 22-24 Monday, Tuesday, Midterm Examinations Thursday-Saturday August 21, Wednesday Holiday (Ninoy Aquino Day) August 26, Monday Holiday (National Heroes’ Day) September 30, October 1-5, Monday-Saturday Final Examinations Second Semester: October 28, 2019 - March 14, 2020 October 28, Monday Classes Begin November 1, Friday Holiday (All Saint’s Day) November 2, Saturday Special Non-working Day November 30, Saturday Holiday (Bonifacio Day) December 2-7, Monday-Saturday Preliminary Examinations December 8, Sunday Immaculate Concepcion Day December 21, Saturday Christmas Vacation Begins January 6, 2019, Monday Classes Resume January 25, Saturday Holiday (Chinese New Year) January 27-31, February 1, Monday-Saturday Midterm Examinations February 11-15, Tuesday-Saturday University Week February 20-22, Thursday -Saturday Final Examinations (graduating) February 25, Thursday Holiday (EDSA Revolution Anniversary) March 9-14, Monday-Saturday Final Examinations (non-graduating) April 4-5, Saturday-Sunday Commencement Exercises SUMMER TERM : APRIL 10, 2020 - MAY 12, 2020 April 6, Monday Classes Begin April 9, Thursday Holiday (Araw ng Kagitingan) April 9-11, Thursday-Saturday Holy Week April 24, Friday Midterm Examinations May 1, Friday Holiday (Labor Day) May 15, Friday Final Examinations This academic calendar was prepared on the assumption that the legal holidays during the time the calendar was prepared to remain as is for the school year. -

Downloads/SR324-Atural%20 Disasters%20As%20Threats%20To%20 Peace.Pdf

The Bedan Research Journal (BERJ) publishes empirical, theoretical, and policy-oriented researches on various field of studies such as arts, business, economics, humanities, health, law, management, politics, psychology, sociology, theology, and technology for the advancement of knowledge and promote the common good of humanity and society towards a sustainable future. BERJ is a double-blind peer-reviewed multidisciplinary international journal published once a year, in April, both online and printed versions. Copyright © 2020 by San Beda University All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without written permission from the copyright owner ISSN: 1656-4049 Published by San Beda University 638 Mendiola St., San Miguel, Manila, Philippines Tel No.: 735-6011 local 1384 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.sanbeda.edu.ph Editorial Board Divina M. Edralin Editor-in-Chief San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Nomar M. Alviar Managing Editor San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Ricky C. Salapong Editorial Assistant San Beda University, Manila, Philippines International Advisory Board Oscar G. Bulaong, Jr. Ateneo Graduate School of Business, Makati City, Philippines Christian Bryan S. Bustamante San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Li Choy Chong University of St. Gallen, Switzerland Maria Luisa Chua Delayco Asian Institute of Management, Makati City, Philippines Brian C. Gozun De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines Raymund B. Habaradas De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines Ricardo A. Lim Asian Institute of Management, Makati City, Philippines Aloysius Ma. A. Maranan, OSB San Beda University, Manila, Philippines John A. -

Philippine Folklore: Engkanto Beliefs

PHILIPPINE FOLKLORE: ENGKANTO BELIEFS HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: Philippine mythology is derived from Philippine folk literature, which is the traditional oral literature of the Filipino people. This refers to a wide range of material due to the ethnic mix of the Philippines. Each unique ethnic group has its own stories and myths to tell. While the oral and thus changeable aspect of folk literature is an important defining characteristic, much of this oral tradition had been written into a print format. University of the Philippines professor, Damiana Eugenio, classified Philippines Folk Literature into three major groups: folk narratives, folk speech, and folk songs. Folk narratives can either be in prose: the myth, the alamat (legend), and the kuwentong bayan (folktale), or in verse, as in the case of the folk epic. Folk speech includes the bugtong (riddle) and the salawikain (proverbs). Folk songs that can be sub-classified into those that tell a story (folk ballads) are a relative rarity in Philippine folk literature.1[1] Before the coming of Christianity, the people of these lands had some kind of religion. For no people however primitive is ever devoid of religion. This religion might have been animism. Like any other religion, this one was a complex of religious phenomena. It consisted of myths, legends, rituals and sacrifices, beliefs in the high gods as well as low; noble concepts and practices as well as degenerate ones; worship and adoration as well as magic and control. But these religious phenomena supplied the early peoples of this land what religion has always meant to supply: satisfaction of their existential needs. -

The Truth of Diwa

The Truth of Diwa Diwa is both the building block and the string upon which all of reality is spun. It permeates all things, and exists in varying states of matter. In a manner of speaking, that chair you see in front of you is Diwa, in a given form. Break it down to its most essential components and you shall see Diwa. However Diwa can be used more than that. It exists in four states: • Agos, Diwa echoing Water. This is the normal state of Diwa, the Diwa that makes up all things. • Tagos, Diwa echoing Air. This is the Diwa that binds things together. It can be manipulated at this level, and if one were to have some means of seeing the invisible machinations of the gods, they will see tiny strands that link everything to everything, as well as the Diwata that embody everything. Diwa in this state can be known as “Fate”, and indeed, the Agents of Heaven call this Tadhana. • Bala, Diwa echoing Fire. This is the Diwa that burns within every living being, and every thing is a living being because everything has a diwata. The Human Eight-Point Soul is made up of this Burning Diwa, and so are the powerful essences of the Karanduun. Burning Diwa can be used to affect other states -- most commonly by having a lot of Burning Diwa, you have more say in how reality works. Thus why Burning Diwa in all beings is known as “Bala”, or “Power”. It is their measure of capability, and it is well known that the Karanduun possess “Unlocked” Bala, which allows their Bala to transcend event that of Gods. -

Occasional Paper No. 68 National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education Teachers College, Columbia University

Occasional Paper No. 68 National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education Teachers College, Columbia University Evaluating Private Higher Education in the Philippines: The Case for Choice, Equity and Efficiency Charisse Gulosino MA Student, Teachers College, Columbia University Abstract Private higher education has long dominated higher education systems in the Philippines, considered as one of the highest rates of privatization in the world. The focus of this paper is to provide a comprehensive picture of the nature and extent of private higher education in the Philippines. Elements of commonality as well as differences are highlighted, along with the challenges faced by private institutions of higher education. From this evidence, it is essential to consider the role of private higher education and show how, why and where the private education sector is expanding in scope and number. In this paper, the task of exploring private higher education from the Philippine experience breaks down in several parts: sourcing of funds, range of tuition and courses of study, per student costs, student destinations in terms of employability, and other key economic features of non-profit /for-profit institutions vis-à-vis public institutions. The latter part of the paper analyses several emerging issues in higher education as the country meets the challenge for global competitiveness. Pertinent to this paper’s analysis is Levin’s comprehensive criteria on evaluating privatization, namely: choice, competition, equity and efficiency. The Occasional Paper Series produced by the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education promotes dialogue about the many facets of privatization in education. The subject matter of the papers is diverse, including research reviews and original research on vouchers, charter schools, home schooling, and educational management organizations. -

Notes on Philippine Divinities

NOTES ON PHILIPPINE DIVINITIES F. LANDA JocANO Introduction THIS PAPER IS ETHNO-HISTORICAL IN NATURE. IT IS DE- signed to put together representative pantheons of different Philippine divinities. The materials for this purpose have been gathered from historical documents, ethnographiC monographs, and Held observations conducted by the writer and other fieldworkers among different indi- genous religious groups in the various parts of the country. No sociological analysis of these cosmologies or their manifest theo- logies is made except to point out that their persistence through time - from the early Spanish contact to the present - indicates they are closely interwoven with the lifeways of the people. The divinities described here are, as they were in the past, conceived as beings with human characteristics. Some of them are good and others are evil. Many stories about the workings of these supernatural beings are told. They participate in the affairs of men. These relationships reinforce local beliefs in the power of the supernatural beings, as those people who participate in community affairs witness how these deities, invoked during complicated rituals, cure an ailing patient or bring about suc- cess in hunting, fishing, and agriculture. Some of these deities are always near; others are inhabitants of far-off realms of the skyworld who take interest in human affairs only when they are invoked during proper ceremonies which compel them to come down to earth. In this connection, the spirits who are always near, are the ones often called upon by the people for help. These supernatural beings are led by the highest ranking deity and not by any one supreme divinity, for each has specific and some independent function. -

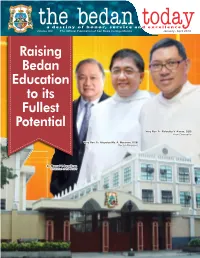

The Bedan Today a D E S T I N Y O F H O N O R, S E R V I C E a N D E X C E L L E N C E Editor in Chief Dr

thea d e s t i n y bedano f h o n o r, s e r v i c e a n dtoday e x c e l l e n c e Volume X IV The Official Publication of San Beda College Manila November January 2014 - April 20152016 Raising Bedan Education to its Fullest Potential Very Rev. Fr. Rafaelito V. Alaras, OSB Prior-Chancellor Very Rev. Fr. Aloysius Ma. A. Maranan, OSB Rector-President Dr. Manuel V. Pangilinan Chairman of the Board the bedan today a d e s t i n y o f h o n o r, s e r v i c e a n d e x c e l l e n c e Editor in Chief Dr. Joffre M. Alajar Contributing Writers Dr. Josefina Manabat Mrs. Teresita Battad Prof. Michael John Rubio Dr. James Loreto Piscos editor'seditor's Mr. Joel Filamor Mr. Jude Roque THE BEDAN TODAY is the official publication of note San Beda College Manila, produced semestrally, note with editorial and business offices at the San Beda Dr. Joffre M. Alajar College Public Relations and Communications Director Office, Mendiola, Manila. Public Relations and Communications Office www.sanbeda.edu.ph Raising Bedan Education to its Fullest Potential The winds of change are being remarkably felt in Philippine Education over the recent months, and these are expected to blow further during the next succeeding years. The K-12 program is prepared to take-off this coming AY 2016-2017. The ASEAN Economic Integration with its concomitant effect on regional educational system is now moving with a surprising speed. -

Huling Bakunawa Allan N

Huling Bakunawa Allan N. Derain Hindi batid ng mga katutubo kung anong uri ng isda iyon yamang hindi pa sila nakakikita nang gayon sa kanilang mga baybayin.Kung kaya itinuring na lamang nila ito bilang isang dambuhala na itinalaga ng Diyos sa malawak na Karagatan ng Silangan dahil sa angkin nitong laki. — Fray Ignacio Francisco Alcina Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas 1668 ang sundan ni datu rabat ang tutok ng hintuturò ng kaniyang panauhin, nagtapos ito sa may bumubulwak na bahagi ng dagat kung saan mapapansin ang mabagal na galaw ng higanteng isda. Ang bakunawa kung tawagin ng mga mangingisda sa gawing ito ng dagat. Ang bunga ng kanilang tatlong araw at tatlong gabing pag-aabang at pagmamatyag kasama ang Tsinong mangangalakal. N Nakatayo si Datu Rabat sa unahan ng kaniyang sinasakyang adyong habang nakamasid sa Tsinong sakay naman ng sariling sampan. Nag-aalala ang datu sa mga piratang maaaring sumalisi sa kaniya. Kaya kailangan niyang bantayan ang mangangalakal na Tsino habang naririto ito sa kaniyang sakop. Kaya siya nagtayo ng bantayog na magbabantay sa kaniyang pantalan. Kaya rin siya umupa ng mga mersenaryong tatambang sa mga pirata. Sa kakayahan niyang magbigay proteksiyon sa mga panauhing mangangalakal nakasalalay 4 likhaan 5 ˙ short story / maikling kuwento ang mabuting pakikitungo sa kaniya ng mga tagasentro. Hindi siya dapat mabigo kahit minsan lalo’t buhat sa Emperador na Anak ng Langit ang kaniyang pinangangalagaang panauhin. Pero dahil parang mga dikya ang mga tulisang dagat na ito na hindi na yata mauubos hangga’t may tubig ang dagat, pinirata na rin niya ang karamihan sa mga pirata para sa ibang sakop na lamang gawin ang kanilang pandarambong. -

Effectiveness of the Multistage Jumping Rope Program in Enhancing the Physical Fitness Levels Among University Students

International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences 8(5): 235-239, 2020 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/saj.2020.080511 Effectiveness of the Multistage Jumping Rope Program in Enhancing the Physical Fitness Levels among University Students Heildenberg C. Dimarucot1,2, Gil P. Soriano3,* 1Department of Human Kinetics, College of Arts and Sciences, San Beda University, Philippines 2Graduate Studies and Transnational Education, Institute of Education, Far Eastern University, Manila, Philippines 3College of Nursing, San Beda University, Philippines Received August 14, 2020; Revised September 11, 2020; Accepted September 29, 2020 Cite This Paper in the following Citation Styles (a): [1] Heildenberg C. Dimarucot, Gil P. Soriano , "Effectiveness of the Multistage Jumping Rope Program in Enhancing the Physical Fitness Levels among University Students," International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 235 - 239, 2020. DOI: 10.13189/saj.2020.080511. (b): Heildenberg C. Dimarucot, Gil P. Soriano (2020). Effectiveness of the Multistage Jumping Rope Program in Enhancing the Physical Fitness Levels among University Students. International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, 8(5), 235 - 239. DOI: 10.13189/saj.2020.080511. Copyright©2020 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Several studies have shown that there has Fitness, Skipping Rope Test, University Students been a sudden decrease in physical activity levels among University students. This is alarming as physical inactivity is a known risk factor for many chronic diseases. Hence, Universities are in the best position to examine the personal and professional lifestyles among their students. -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta.