Community Engagement and Organizing Handbook for University Extension Workers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paganninawanvol

THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT - REGION 1 PAGANNINAWANVOL. 11 NO. 2 APRIL - JUNE 2015 DILG R1 engages 334 youth leaders for WEmboree The Department of the Interior and Local Government Region 1 (DILG R1) gathered 334 youth leaders in the Region for the conduct of WEmboree, a disaster - resiliency camp, in the provinces of Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, and Pangasinan last May 21-22, 2015 and in the province of La Union last May 22-23, 2015. These youth leaders come from the following: 75 from 18 local government units (LGUs) and three (3) Local Resource Institutes (LRIs) of Ilocos Norte, 81 from 31 LGUs of Ilocos Sur, 94 from 15 LGUs of La Union and 84 from 32 LGUs of Pangasinan. The WEmboree of the four (4) provinces were simultaneously conducted at Marcos Stadium, Laoag City, Ilocos Norte; Philippine Science High School, San Ildefonso, Ilocos Sur; Camp Diego Silang, Carlatan, City of San Fernando, La Union; and Narciso Ramos Sports and Civic Center, Lingayen, Pangasinan.(continued at page 6) WHAT’S INSIDE Ilocos Sur receives 2014 PCF p.2 DILG R1 preps 32 LGUs on BuB-PWS p.3 DILG-Ilocos Norte launces UBAS p.5 Balaoan, LU launches Operation Pinili, IN conducts CBMS App Training p.8 Teenager from Cabugao, IS awarded Listo p.7 with Gawad Kalasag p.11 2 The Official Newsletter of the Department of the Interior and Local Government - Region 1 RPOC 1: Bring government Province of Ilocos Sur closer to affected areas, receives 2014 PCF solve insurgency The Regional Peace and Order Council (RPOC) 1 has recently agreed that the most practical approach to resolve insurgency problems in the Region is to bring the government and its services closer to the affected armed-conflict areas. -

SARE, Vol. 58, Issue 1 | 2021

SARE, Vol. 58, Issue 1 | 2021 Making Space for Myth: Worldbuilding and Interconnected Narratives in Mythspace Francis Paolo Quina University of the Philippines-Diliman, Quezon City, the Philippines Abstract The comics medium has long proven to be fertile ground for worldbuilding, spawning not only imaginary worlds but multiverses that have become international transmedial franchises. In the Philippines, komiks (as it is called locally) has provided the Filipino popular imagination with worlds populated by superheroes, super spies, supernatural detectives, and creatures from different Philippine mythologies. The komiks series Mythspace, written by Paolo Chikiamco and illustrated by several artist-collaborators, takes the latter concept, and launches it into outer space. Classified by its own writer as a “Filipino space opera” consisting of six loosely interconnected stories, Mythspace presents a storyworld where the creatures of Philippine lower mythologies are based on various alien species that visited the Philippines long ago. The article will examine the use of interconnected narratives as a strategy for worldbuilding in Mythspace. Drawing from both subcreation and comic studies, this article posits that interconnected narratives is a worldbuilding technique particularly well-suited to comics, and that the collaborative nature of the medium allows for a diversity of genres and visual styles that can be used by future komiks creators to develop more expansive storyworlds. Keywords: comics studies, subcreation studies, storyworlds, Mythspace, the Philippines The comics medium has long proven to be fertile ground for worldbuilding. It has spawned not only storyworlds in the pages of comic books and graphic novels but given birth to multiverses of storytelling across several media. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang's Legacy Through Stagecraft

Dominican Scholar Humanities & Cultural Studies | Senior Liberal Arts and Education | Theses Undergraduate Student Scholarship 5-2020 Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang’s Legacy through Stagecraft Leeann Francisco Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2020.HCS.ST.02 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Francisco, Leeann, "Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang’s Legacy through Stagecraft" (2020). Humanities & Cultural Studies | Senior Theses. 2. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2020.HCS.ST.02 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberal Arts and Education | Undergraduate Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Humanities & Cultural Studies | Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang’s Legacy through Stagecraft By Leeann Francisco A culminating thesis submitted to the faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Humanities Dominican University of California San Rafael, CA May 2020 ii Copyright © Francisco 2020. All rights reserved iii ABSTRACT Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang’s Legacy through Stagecraft is a chronicle of the scriptwriting and staging process for Bannuar, a historical adaptation about the life of Gabriela Silang (1731-1763) produced by Dominican University of California’s (DUC) Filipino student club (Kapamilya) for their annual Pilipino Cultural Night (PCN). The 9th annual show was scheduled for April 5, 2020. Due to the limitations of stagecraft, implications of COVID-19, and shelter-in-place orders, the scriptwriters made executive decisions on what to omit or adapt to create a well-rounded script. -

Art Archive 02 Contents

ART ARCHIVE 02 CONTENTS The Japan Foundation, Manila A NEW AGE OF CONTEMPORARY PHILIPPINE CINEMA AND LITERATURE ART ARCHIVE 02 by Patricia Tumang The Golden Ages THE HISTORIC AND THE EPIC: PHILIPPINE COMICS: Contemporary Fiction from Mindanao Tradition and Innovation by John Bengan Retracing Movement Redefiningby Roy Agustin Contemporary WHAT WE DON’T KNOW HistoriesABOUT THE BOOKS WE KNOW & Performativity Visual Art by Patricia May B. Jurilla, PhD SILLIMAN AND BEYOND: FESTIVALS AND THE LITERARY IMAGINATIONS A Look Inside the Writers’ Workshop by Andrea Pasion-Flores by Tara FT Sering NEW PERSPECTIVES: Philippine Cinema at the Crossroads by Nick Deocampo Third Waves CURRENT FILM DISTRIBUTION TRENDS IN THE PHILIPPINES by Baby Ruth Villarama DIGITAL DOCUMENTARY TRADITIONS Regional to National by Adjani Arumpac SMALL FILM, GLOBAL CONNECTIONS Contributor Biographies by Patrick F. Campos A THIRD WAVE: Potential Future for Alternative Cinema by Dodo Dayao CREATING RIPPLES IN PHILIPPINE CINEMA: Directory of Philippine The Rise of Regional Cinema by Katrina Ross Tan Film and Literature Institutions ABOUT ART ARCHIVE 02 The Japan Foundation is Japan’s only institution dedicated to carrying out comprehensive international cultural exchange programs throughout the world. With the objective of cultivating friendship and ties between Japan and the world through culture, language, and dialogue, the Japan Foundation creates global opportunities to foster trust and mutual understanding. As the 18th overseas office, The Japan Foundation, Manila was founded in 1996, active in three focused areas: Arts and Culture; Japanese Studies and Intellectual Exchange; Japanese- Language Education. This book is the second volume of the ART ARCHIVE series, which explores the current trends and concerns in Philippine contemporary art, published also in digital format for accessibility and distribution on a global scale. -

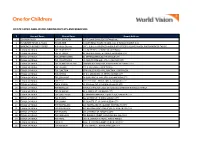

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published By

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published by: NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila Philippines Research and Publications Division: REGINO P. PAULAR Acting Chief CARMINDA R. AREVALO Publication Officer Cover design by: Teodoro S. Atienza First Printing, 1990 Second Printing, 1996 ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 003 — 4 (Hardbound) ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 006 — 9 (Softbound) FILIPINOS in HIS TOR Y Volume II NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 Republic of the Philippines Department of Education, Culture and Sports NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE FIDEL V. RAMOS President Republic of the Philippines RICARDO T. GLORIA Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports SERAFIN D. QUIASON Chairman and Executive Director ONOFRE D. CORPUZ MARCELINO A. FORONDA Member Member SAMUEL K. TAN HELEN R. TUBANGUI Member Member GABRIEL S. CASAL Ex-OfficioMember EMELITA V. ALMOSARA Deputy Executive/Director III REGINO P. PAULAR AVELINA M. CASTA/CIEDA Acting Chief, Research and Chief, Historical Publications Division Education Division REYNALDO A. INOVERO NIMFA R. MARAVILLA Chief, Historic Acting Chief, Monuments and Preservation Division Heraldry Division JULIETA M. DIZON RHODORA C. INONCILLO Administrative Officer V Auditor This is the second of the volumes of Filipinos in History, a com- pilation of biographies of noted Filipinos whose lives, works, deeds and contributions to the historical development of our country have left lasting influences and inspirations to the present and future generations of Filipinos. NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 MGA ULIRANG PILIPINO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lianera, Mariano 1 Llorente, Julio 4 Lopez Jaena, Graciano 5 Lukban, Justo 9 Lukban, Vicente 12 Luna, Antonio 15 Luna, Juan 19 Mabini, Apolinario 23 Magbanua, Pascual 25 Magbanua, Teresa 27 Magsaysay, Ramon 29 Makabulos, Francisco S 31 Malabanan, Valerio 35 Malvar, Miguel 36 Mapa, Victorino M. -

Petition to Object to the Nucor Steel Facility, St. James Parish, Louisiana

BEFORE THE ADMINISTRATOR U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY In the Matter of Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality's Proposed Operating Permit and Prevention of Significant Deterioration Permit for Consolidated Environmental Management, Inc./Nucor Steel, Louisiana, St. James Parish, Louisiana LDEQ Agency Interest No. 157847 Activity Nos. PER2008000 1 and PER20080002 Permit Nos. 2560-00281-VO; PSD-LA-740 Proposed to Nucor Steel, Louisiana By the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality on October 15 ,2008 PETITION REQUESTING THAT THE ADMINISTRATOR OBJECT TO THE TITLE V OPERATING AND PREVENTION OF SIGNIFICANT DETERIORATION PERMITS PROPOSED FOR NUCOR STEEL, LOUISIANA Pursuant to Section 505(b) of the Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7661 deb )(2) and 40 C.F.R. §70.8( d) , Zen-Noh Grain Corporation ("Zen-Noh") petitions the Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ("Administrator") to object to Title V Air Operating Permit (No. 2560-00281 -VO) ("Operating Permit"). Zen-Noh also petitions the Administrator to reopen or revise Prevention of Significant Deterioration Permit (No. PSD-LA-740) ("PSD Pennit"). And, Zen-Noh petitions the Administrator to direct Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality ("LDEQ") to provide Zen-Noh and the public with all information necessary to the issuance or denial of the Operating Pennit and PSD Permit, provide a meaningful period for public review, and reopen the public comment period. Both the Operating Permit and PSD Permit were proposed on or about October 15, 2008 by LDEQ for issuance to Consolidated Environmental Management, Inc.INucor Steel Louisiana ("Nucor") for a Pig Iron Manufacturing Plant in St. James Parish, Louisiana. -

Effects of Selected Phonetic Aspects in 'Hie

EFFECTS OF SELECTED PHONETIC ASPECTS IN 'HIE TRANSMISSION OF THE SPANISH LANGUAGE DISSERTATION Presentod in Partial Fulfillment of tho Requirement* for tho Dogroe Doctor of Philosophy in tho Graduate School of The Ohio State University Dy CRUZ AURELIA CANCEL FERRER HARDIGREE, D.A., M.S. Tho Ohio State University 1957 Approved by: 7 Adviser / Department of Speech TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION............... 1 The Spanish Language in America ................ 1 General Characteristics and Minor Variations Among Spanish-Americans.............. 0 General Characteristics . ................ 9 S e s e o ................................. g Y e f s m o .............................. 10 Minor Variations .... ....... ...... 12 Orthographio ® > [s] .................... 12 Ceceo . 12 Orthographic x > C3 3, Cs3, Cg*3» Cko3 . 13 Orthographic r and rr> [r3 [ r ] ......... 14 Orthographic d > [ d 3 ....... ,. .......... 15 V o w e l s ......... 16 Orthographic-Phonetic Sound System ............. 17 Orthographio-Phonetic Units ................ 17 Consonants ..... ...... 17 V o w e l s ............................... 20 D i p h t h o n g s ........................... 22 S u m mary.................................... 23 II. PURPOSE AND R A T I O N A L E ............................ 25 III. REVIEW OF JEHEILITERATURE.......................... 28 Tests Developed to Evaluate Equipment ........... 29 Bell Telephone Tests ........... 29 Harvard (Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory) Tests. 30 Spanish Test for Hearing A i d s ........... 32 Tests Developed to Evaluate Speakers and Listeners ................ .......... 33 Jones Enunciation Test .......... 33 Voice Communication Laboratory (Waco) Write-Down Lists ............ 33 Multiple-Choice Tests ..... ......... 34 Spanish Speech Reception Test ......... 35 Tests Developed to Study the M e s s a g e ........... 36 Intelligibility of Sounds ......... 36 Intelligibility of English Words ....... 37 Intelligibility of Spanish Words ...... -

20000 Gather at UST for 40Th Humanae Vitae Celebrations

THE ACADEMIA OFFICIAL INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF SANTO TOMAS VOL. XXXV NO. 3 JULY-SEPTEMBER 2008 REV. FR. ISIDRO C. ABAÑO, O.P. COORDINATOR CORRESPONDENTS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Dr. Mafel C. Ysrael/ Academic Affairs ASSOC. PROF. GIOVANNA V. FONTANILLA Dr. Josephine G. Relis/ Accountancy EDITOR Ms. Ma. Michelle A. Lauzon/ Admissions Office Mr. Erickson D. Pabalan/ Alumni Relations Archt. Alice T. Maghuyop/ Architecture DR. JAIME I. ROMERO Assoc. Prof. Lino N. Baron/ Arts and Letters ASSOCIATE EDITOR Assoc. Prof. Richard C. Pazcoguin/ Center for Campus Ministry Mr. Alfred A. Dimalanta/ Center for Creative Writing and Studies MR. JONATHAN T. GAMALINDA Assoc. Prof. Eric B. Zerrudo/ Center for the Conservation of Cultural ART DIRECTOR Property and Environment in the Tropics Fr. Pablo Tiong, O.P. / Center for Contextualized Theology and Applied Ethics MS. MARIA REINA M. SERADOR Dr. Rodrigo A. Litao/ Center for Educational Research and Development STAFF WRITER Atty. Ricardo M. Magtibay/ Civil Law Asst. Prof. Fe D. Bruselas/ Commerce Ms. Lauren Regina S. Villarama/ Community Development MS. JHONA L. FREO Mr. Joel C. Sagut/ Ecclesiastical Faculties CIRCULATION MANAGER Asst. Prof. Joel L. Adamos/ Education Dr. Andres Julio V. Santiago/ Education High School MR. ARISTOTLE B. GARCIA Mr. Leandre Andres S. Dacanay/ Educational Technology Center MS. BASILIA A. LANUZA Asst. Prof. Virginia A. Sembrano/ Engineering CIRCULATION ASSISTANTS Asst. Prof. Jean I. Reintegrado/ Fine Arts and Design Dr. Michael Anthony C. Vasco/ Graduate School MR. ARISTOTLE B. GARCIA Mr. Vincent Glenn P. Lape/ Grants Ms. Marissa S. Nicasio/ Guidance and Counselling Office MS. MARIA REINA M. SERADOR Junior Teacher Emmanuel M. -

THE GENESIS of the PHILIPPINE COMMUNIST PARTY Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. Dames Andrew Richardson School of Orienta

THE GENESIS OF THE PHILIPPINE COMMUNIST PARTY Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. dames Andrew Richardson School of Oriental and African Studies University of London September 198A ProQuest Number: 10673216 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673216 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Unlike communist parties elsewhere in Asia, the Partido Komunista sa Pilipinas (PKP) was constituted almost entirely by acti vists from the working class. Radical intellectuals, professionals and other middle class elements were conspicuously absent. More parti cularly, the PKP was rooted In the Manila labour movement and, to a lesser extent, in the peasant movement of Central Luzon. This study explores these origins and then examines the character, outlook and performance of the Party in the first three years of its existence (1930-33). Socialist ideas began to circulate during the early 1900s, but were not given durable organisational expression until 1922, when a Workers’ Party was formed. Led by cadres from the country's principal labour federation, the Congreso Obrero, this party aligned its policies increasingly with those of the Comintern. -

Assessing ASEAN-China Relations

ISSUE 6/2018 25 DECEMBER 2018 ISSN: 2424–8045 ASEAN Braces for ASEAN-China ASEAN Amidst Building Blocks Batik: The Wax that a Risen China Dialogue Relations: the US-China Towards Resilient & Never Wanes Young but Mature Rivalry Innovative ASEAN Assessing ASEAN-China Relations ASEANFocus is published by the ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and available electronically at www.iseas.edu.sg Contents If you wish to receive an electronic copy of ASEANFocus, please email us at [email protected] Editorial Notes Published on 26 December 2018 Analysis EDITORIAL CHAIRMAN 2 ASEAN Braces for a Risen China Choi Shing Kwok Steven Wong MANAGING EDITOR 4 ASEAN-China Dialogue Relations: Young but Mature Tang Siew Mun Zha Daojiong and Dong Ting PRODUCTION EDITOR 6 ASEAN Amidst the US-China Rivalry Hoang Thi Ha Dewi Fortuna Anwar EDITORIAL COMMITTEE 8 ASEAN Centrality in Testing Times Moe Thuzar Herman Kraft Termsak Chalermpalanupap 10 ASEAN’s Ambivalence Towards a “Common EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Destiny” with China Pham Thi Phuong Thao Hoang Thi Ha ASEAN in Figures 12 ASEAN-China Relations: Then and Now Insider Views 14 Mohamad Maliki Bin Osman: Building Blocks Towards a Resilient and Innovative ASEAN Sights and Sounds 17 Batik: The Wax that Never Wanes SUPPORTED BY Hayley Winchcombe 20 University of Santo Tomas: Timeless and Forever Timely Nur Aziemah Aziz Year in Review The responsibility for facts and 22 Images and Insights opinions in this publication rests exclusively with the authors 24 ASEAN Highlights in 2018 and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or the policy of ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute or its supporters.