China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 [Online], Online Since 25 April 2007, Connection on 04 October 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection and Management Plan on Kaiping Diaolou and Villages

Name of project Protection and Management Plan on Kaiping Diaolou and Villages Entrusting party People's ~overnmentof Kaiping City, Guangdong Province Undertaking party Urban Planning and Design Center of Peking University Director of the center Professor Xie Ninggao Heads of Project Professor He Luping Dr. Shen Wenquan Preparer Wu Honglin, Chen Yaohua, Song Feng, Zheng Xinzhou, Han Xiangyi, Cao Lijuan, Xuhui, Jiang Piyan, Chen Rui Co-sponsors Kaiping Office of Protection and Management of Diaolou and Villages Land Administration Bureau of Kaiping Planning Burea of Kaiping Wuyi University Completion time December 2001 Contents I . Background of the planning 1.1 Background of the planning .....................................................1 1.2 Scope of the planning ........................................................... 2 . 1.3 Natural cond~t~ons............................................................... 2 1.4 Historical development .........................................................3 1.5 Socio-cconomic conditions .................................................... 3 11 . Analysis of property resources 2.1 Distribution of Kaiping Diaolou and Villages ...............................5 2.2 Description of the cultural heritage in the planned area ....................6 2.3 Spaces characteristics of the properties ...................................... I I 2.4 Value of the properties ......................................................... I3 111 . Current situation and analysis of the protection 3.1 Current situation of the -

"Thoroughly Reforming Them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude"

By Adrian Zenz - Version of this paper accepted for publication by the journal Central Asian Survey "Thoroughly Reforming Them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude" - China's Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang1 Adrian Zenz European School of Culture and Theology, Korntal Updated September 6, 2018 This is the accepted version of the article published by Central Asian Survey at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02634937.2018.1507997 Abstract Since spring 2017, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China has witnessed the emergence of an unprecedented reeducation campaign. According to media and informant reports, untold thousands of Uyghurs and other Muslims have been and are being detained in clandestine political re-education facilities, with major implications for society, local economies and ethnic relations. Considering that the Chinese state is currently denying the very existence of these facilities, this paper investigates publicly available evidence from official sources, including government websites, media reports and other Chinese internet sources. First, it briefly charts the history and present context of political re-education. Second, it looks at the recent evolution of re-education in Xinjiang in the context of ‘de-extremification’ work. Finally, it evaluates detailed empirical evidence pertaining to the present re-education drive. With Xinjiang as the ‘core hub’ of the Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing appears determined to pursue a definitive solution to the Uyghur question. Since summer 2017, troubling reports emerged about large-scale internments of Muslims (Uyghurs, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz) in China's northwest Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). By the end of the year, reports emerged that some ethnic minority townships had detained up to 10 percent of the entire population, and that in the Uyghur-dominated Kashgar Prefecture alone, numbers of interned persons had reached 120,000 (The Guardian, January 25, 2018). -

Greater Bay Area Logistics Markets and Opportunities Colliers Radar Logistics | Industrial Services | South China | 29 May 2020

COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 Rosanna Tang Head of Research | Hong Kong SAR and Southern China +852 2822 0514 [email protected] Jay Zhong Senior Analyst | Research | Guangzhou +86 20 3819 3851 [email protected] Yifan Yu Assistant Manager | Research | Shenzhen +86 755 8825 8668 [email protected] Justin Yi Senior Analyst | Research | Shenzhen +86 755 8825 8600 [email protected] GREATER BAY AREA LOGISTICS MARKETS AND OPPORTUNITIES COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INSIGHTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 3 MAP OF GBA LOGISTICS MARKETS AND RECOMMENDED CITIES 4 MAP OF GBA TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM 5 LOGISTICS INDUSTRY SUPPLY AND DEMAND 6 NEW GROWTH POTENTIAL AREA IN GBA LOGISTICS 7 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – ZHUHAI-ZHONGSHAN-JIANGMEN 8 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – SHENZHEN-DONGGUAN-HUIZHOU 10 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – GUANGZHOU-FOSHAN-ZHAOQING 12 2 COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 Insights & Recommendations RECOMMENDED CITIES This report identifies three logistics Zhuhai Zhongshan Jiangmen clusters from the mainland Greater Bay The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau We expect Zhongshan will be The manufacturing sector is Area (GBA)* cities and among these Bridge Zhuhai strengthens the a logistics hub with the now the largest contributor clusters highlights five recommended marine and logistics completion of the Shenzhen- to Jiangmen’s overall GDP. logistics cities for occupiers and investors. integration with Hong Kong Zhongshan Bridge, planned The government aims to build the city into a coastal logistics Zhuhai-Zhongshan-Jiangmen: and Macau. for 2024, connecting the east and west banks of the Peral center and West Guangdong’s > Zhuhai-Zhongshan-Jiangmen’s existing River. -

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

春眠曙不開。 Shy to Rise Because of Their Complexions; 4 Too Frail to Come to the Sound of Voices

王右丞集卷之二古詩 Juan 2: Old style poems 2.1–2.5 2.1–2.5 扶南曲歌詞五首 Five Lyrics for the Funan Melody 1. 1. 翠羽流蘇帳, Tasseled curtains with kingfisher feathers Stay unopened at dawn as they sleep in spring. 春眠曙不開。 Shy to rise because of their complexions; 4 Too frail to come to the sound of voices. 羞從面色起, Early at the Zhaoming Palace 4 嬌逐語聲來。 Eunuch envoys of their lord bid them hasten.1 早向昭陽殿, 君王中使催。 2. 2. 堂上青絃動, Up in the hall the blue strings twang, While before the hall the intricate mats are spread. 堂前綺席陳。 A song of Qi– a ballad from Lady Lu; 4 Paired dancers, girls from Luoyang.2 齊歌盧女曲, But he only watches these kingdom-toppling beauties; 4 雙舞洛陽人。 Who can know whom his heart holds dear? 傾國徒相看, 寧知心所親。 1 Zhaoming Palace: a women’s quarters in Han times; used since then as a general term for the quarters of imperial favorites. 2 Lady Lu was a court lady from the time of Emperor Wu武 of the Wei魏 (Cao Cao曹操). She was famous for her musical talents. One piece in her repertoire was a melody from Qi called“The Pheasants Fly at Dawn.” Women from Luo- yang were famous in popular verse for their beauty. Open Access. © 2020 Paul Rouzer, published by De Gruyter. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501516023-002 王右丞集卷之二古詩 Juan 2: Old style poems 2.1–2.5 2.1–2.5 扶南曲歌詞五首 Five Lyrics for the Funan Melody 1. -

Tier 1 Factories No

Tier 1 Factories No. Females Factory Address No. No. male Audit Factory Name Province Country Category Female in Mgmt (= Street # / Town / City) Workers workers Rating Workers roles Dixiang Shoes Factory No.1, Street 12, Xinxing Road 3, Huangbu Town, Huidong county Guangdong China Footwear Anhui Hemao Zhongyi garment co., ltd No. 17 Wanshui Rd, Qianshan County Comprehensive Economic Development Zone,Anqing, Anhui China Apparel 150 30 120 10 Bogart Lingerie (Shenzhen) Ltd No 28-29 Building, No 3 Industrial Park Citanpu Community Gong Ming New District Shenzhen China Apparel 900 300 600 4 Chang Shu Qing Chuan Knitting Co.,LTD. Zhou Jia Qiao Village,Xin Gang Town,Chang Shu City,Jiang Su Jiangsu China Apparel 120 24 96 7 Changzhou Runyu Co Ltd No.23, Chun Qiu Road, Hutang, Changzhou Jiangsu China Apparel 106 30 76 20 ChangZhou Shenglai Garments Co. Ltd No.1 Kele Road, Xinbei District, Changzhou Jiangsu China Apparel 214 45 169 35 Dongguan Shun Fat Underwear Manufactory Ltd Jiaoli Village, Zhongtang Town, Dongguan City, Guangdong Dongguan China Apparel 414 142 272 Dongxing garment factory (sweater factory) 3rd floor,No.15,Baoshu road,Baiyun district,Guangzhou Guangdong China Apparel 40 15 25 5 Guangdong Oleno Underwear Group Co., Ltd. No.1 North of Jianshe Road, Bichong, Huangqi, Nanhai District, Foshan City Guangdong China Apparel 588 143 445 48 Guangzhou Guanjie Garment Co. Ltd (+Hong Bei) 4th Floor ,Building D ,Shiqi Village ,Shilian Road ,Shiji Town ,Panyu District ,Guangzhou Guangdong China Apparel 85 32 53 4 Guangzhou Hanchen Garment Company 3rd Floor, No.8, Lane 2, Shajiao Middle Road, Xiajiao Town, Panyu District Guangzhou China Apparel 53 21 32 6 Guangzhou Hejin Garment Co. -

2019 International Religious Freedom Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, XINJIANG, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary Reports on Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Xinjiang are appended at the end of this report. The constitution, which cites the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the guidance of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, states that citizens have freedom of religious belief but limits protections for religious practice to “normal religious activities” and does not define “normal.” Despite Chairman Xi Jinping’s decree that all members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) must be “unyielding Marxist atheists,” the government continued to exercise control over religion and restrict the activities and personal freedom of religious adherents that it perceived as threatening state or CCP interests, according to religious groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international media reports. The government recognizes five official religions – Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism. Only religious groups belonging to the five state- sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” representing these religions are permitted to register with the government and officially permitted to hold worship services. There continued to be reports of deaths in custody and that the government tortured, physically abused, arrested, detained, sentenced to prison, subjected to forced indoctrination in CCP ideology, or harassed adherents of both registered and unregistered religious groups for activities related to their religious beliefs and practices. There were several reports of individuals committing suicide in detention, or, according to sources, as a result of being threatened and surveilled. In December Pastor Wang Yi was tried in secret and sentenced to nine years in prison by a court in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, in connection to his peaceful advocacy for religious freedom. -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

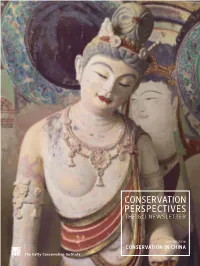

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Chinese Herbal Medicine for Endometriosis (Review)

Chinese herbal medicine for endometriosis (Review) Flower A, Liu JP, Chen S, Lewith G, Little P This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 3 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Chinese herbal medicine for endometriosis (Review) Copyright © 2009 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 2 BACKGROUND .................................... 3 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 4 METHODS ...................................... 4 RESULTS....................................... 5 Figure1. ..................................... 7 Figure2. ..................................... 8 DISCUSSION ..................................... 10 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 11 REFERENCES ..................................... 11 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 17 DATAANDANALYSES. 27 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 CHM versus gestrinone, Outcome 1 Symptomatic relief. 28 Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 CHM versus gestrinone, Outcome 2 Symptomatic relief rate (intention-to-treat). 29 Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 CHM versus gestrinone, Outcome 3 Pregnant rate (accumulated from 3-24 months of follow- up)...................................... 29 Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 CHM versus danazol, Outcome 1 Symptomatic relief. 30 Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 -

China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 the Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) 2

China Perspectives 66 | July- August 2006 Varia The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) Buildings for dangerous times Patricia R.S. Batto Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1033 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1033 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2006 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Patricia R.S. Batto, « The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) », China Perspectives [Online], 66 | July- August 2006, Online since 01 June 2007, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1033 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1033 This text was automatically generated on 28 October 2019. © All rights reserved The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) 1 The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) Buildings for dangerous times Patricia R.S. Batto EDITOR'S NOTE Translated from the French original by Jonathan Hall I would particularly like to thank Annie Au-Yeung for her valuable help in preparing this article. 1 To the west of the Pearl River Delta, in villages nestling amid green bamboo and banana groves and surrounded by a patchwork of rice paddies, stand a number of incongruous dark towers bristling with battlements, fearsome fortresses full of arrow slits, and even the occasional elegant turret above an ornate mansion. All these buildings, in the middle of the Chinese countryside, look like faint reflections of a distant West. How did they end up on the banks of the Kaiping rice paddies? 2 Kaiping is situated in south-western Guangdong and, according to official figures, has 1,833 of these buildings or diaolou1, most of which were built in the early twentieth century. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check