China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 the Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection and Management Plan on Kaiping Diaolou and Villages

Name of project Protection and Management Plan on Kaiping Diaolou and Villages Entrusting party People's ~overnmentof Kaiping City, Guangdong Province Undertaking party Urban Planning and Design Center of Peking University Director of the center Professor Xie Ninggao Heads of Project Professor He Luping Dr. Shen Wenquan Preparer Wu Honglin, Chen Yaohua, Song Feng, Zheng Xinzhou, Han Xiangyi, Cao Lijuan, Xuhui, Jiang Piyan, Chen Rui Co-sponsors Kaiping Office of Protection and Management of Diaolou and Villages Land Administration Bureau of Kaiping Planning Burea of Kaiping Wuyi University Completion time December 2001 Contents I . Background of the planning 1.1 Background of the planning .....................................................1 1.2 Scope of the planning ........................................................... 2 . 1.3 Natural cond~t~ons............................................................... 2 1.4 Historical development .........................................................3 1.5 Socio-cconomic conditions .................................................... 3 11 . Analysis of property resources 2.1 Distribution of Kaiping Diaolou and Villages ...............................5 2.2 Description of the cultural heritage in the planned area ....................6 2.3 Spaces characteristics of the properties ...................................... I I 2.4 Value of the properties ......................................................... I3 111 . Current situation and analysis of the protection 3.1 Current situation of the -

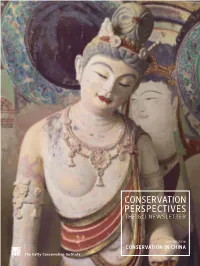

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

Kulangsu Gardens and Conservation Measures Undertaken

additional information on disaster preparedness, the relation of the proposed Outstanding Universal Value to the Kulangsu gardens and conservation measures undertaken. A (China) response was received from the State Party on 23 November 2016. No 1541 On 20 December 2016, ICOMOS sent an Interim Report to the State Party, which contained further requests for additional information on the justification for the proposed Official name as proposed by the State Party Outstanding Universal Value, protection of the property Kulangsu: A historic international settlement and its visitor management. The State Party responded on 22 February 2017. All additional information has been Location incorporated into the relevant sections below. Fujian Province China Date of ICOMOS approval of this report 10 March 2017 Brief description Kulangsu is a tiny island located at the estuary of Chiu-lung River facing the 600 metres distant city of Xiamen across the Lujiang Strait. Based on earlier traditional settlements, 2 The property the international settlement, which formally carries this title since 1903, integrated influences of foreigners living there Description is the late 19th century in the vicinity of Yiamen international The nominated property covers the entire island of port and later in the early 20th century of Chinese returning Kulangsu and its adjacent coastal waters with an overall from abroad. Its heritage reflects the composite nature of size of 316.2 hectares. The boundaries in the waters are a modern settlement composed of 931 historical buildings demarcated by the extension of the surrounding coral reefs. of a variety of local and international architectural styles, The buffer zone, which covers the adjacent Dayu and natural sceneries, a historic network of roads and historic Monkey islands and reaches until the shoreline of Xiamen, gardens. -

Global Art and Heritage Law Series China

GLOBAL ART AND HERITAGE LAW SERIES | CHINA REPORT GLOBAL ART AND HERITAGE LAW SERIES CHINA Prepared for Prepared by In Collaboration with COMMITTEE FOR A VOLUNTEER LAW FIRM CULTURAL POLICY FOR TRUSTLAW 2 GLOBAL ART AND HERITAGE LAW SERIES | CHINA REPORT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report has been prepared in collaboration with TrustLaw, the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s global, legal pro bono service that connects law firms and legal teams to non-governmental organisations and social enterprises that are working to create social and environmental change. The Thomson Reuters Foundation acts to promote socio-economic progress and the rule of law worldwide. The Foundation offers services that inform, connect and ultimately empower people around the world: access to free legal assistance, media development and training, editorial coverage of the world’s under-reported stories and the Trust Conference. TrustLaw is the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s global pro bono legal service, connecting the best law firms and corporate legal teams around the world with high-impact NGOs and social enterprises working to create social and environmental change. We produce groundbreaking legal research and offer innovative training courses worldwide. Through TrustLaw, over 120,000 lawyers offer their time and knowledge to help organisations achieve their social mission for free. This means NGOs and social enterprises can focus on their impact instead of spending vital resources on legal support. TrustLaw’s success is built on the generosity and commitment of the legal teams who volunteer their skills to support the NGOs and social enterprises at the frontlines of social change. By facilitating free legal assistance and fostering connections between the legal and development communities we have made a huge impact globally. -

Architecture, Space, and Society in Chinese Villages, 1978-2018

Wesleyan University The Honors College Constructing Nostalgic Futurity: Architecture, Space, and Society in Chinese Villages, 1978-2018 by Juntai Shen Class of 2018 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors from the College of Social Studies and with Departmental Honors in Art History Middletown, Connecticut April, 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgement - 2 - [Introduction] A Playground for Minds and Actions Modern Chinese Villages - 4 - [Chapter 1] Houses as a Mirror of the Boom and Bust Liangjia’s Spontaneous Path of Architectural Development - 27 - [Chapter 2] A Socialist Paradise on Earth Huaxi’s Story of Socialist Great Revival - 59 - [Chapter 3] Intermingled Sounds of Chickens and Dogs Wencun’s Cultural and Aesthetic Experiment - 103 - [Epilogue] The Presence of Nostalgic Futurity - 135 - Research Bibliography - 144 - Image Appendix - 154 - 1 Acknowledgement This project would not have come to fruition were it not for the help of a host of gracious people along the way. Firstly, I am deeply indebted to my thesis advisors, Professors Joseph Siry and Ying Jia Tan. Professor Siry’s infinite knowledge of architectural history and global culture, as well as his incredible work efficiency and sharp criticism pushed me to become a better thinker, writer, and human being. Professor Tan’s high academic standard, and more importantly, his belief in my idea and vision gave me confidence through all the ups and downs during the writing process. I will always treasure my conversations with both about China, villages, buildings, arts, and beyond. -

Sustainable Tourism Development---How Sustainable Are China’S Cultural Heritage Sites

SUSTAINABLE TOURISM DEVELOPMENT---HOW SUSTAINABLE ARE CHINA’S CULTURAL HERITAGE SITES Dan Liao Tourism & Hospitality Department, Kent State University, OH, 44240 E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Philip Wang Kent State University Abstract In many countries around the world, the UNESCO World Heritage sites are major tourist attractions. The purpose of this study is to examine the level of sustainability of 28 cultural heritage sites in the People’s Republic of China. An analysis of the official websites of the –28 heritage sites was conducted using five sustainable development criteria: authenticity, tourists’ understanding of cultural value, commercial development, cooperation with the tourism industry and the quality of life in the community. Results showed most of the tourism destinations did well in authenticity preservation, commercial development and in obtaining economic revenue. For sustainable management of the sites, it was recommended that more attention should be paid to tourists’ understanding, tourism stakeholders’ collaboration and the environment of the community. As such, a triangular relationship is formed with management authorities, commercial enterprises and the community. 1.0 Introduction The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has considered World Heritage Sites in order to safeguard unique and outstanding properties for humankind in three categories: cultural, natural and mixed. Of the 911 sites around the world, 40 are located in People’s Republic of China, including 28 cultural, 8 natural and 4 mixed sites (Unesco.org). Cultural heritage tourism is defined as “visits by persons from outside the host community motivated wholly or in part by interest in historical, artistic, scientific or life style /heritage offerings of a community, region, group or institution” (Silberberg, 1995, p.361). -

To View the List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in China

List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in China Time in the List Heritage Sites Location Category 1987 The Great Wall Beijing Cultural Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing 1987, 2004 Dynasties (Forbidden City and Mukden Beijing Cultural Palace) Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor (Terra- 1987 Xi'an, Shaanxi Cultural Cotta Warrior) Cultural and 1987 Mount Taishan Tai'an, Shandong Natural 1987 Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian Beijing Cultural 1987 Mogao Grottoes Dunhuang, Gansu Cultural Cultural and 1990 Mount Huangshan Huangshan, Anhui Natural Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic and Historic Interest 1992 Jiuzhaigou, Sichuan Natural Area 1992 Wulingyuan Scenic and Historic Interest Area Zhangjiajie, Hunan Natural 1992 Huanglong Scenic and Historic Interest Area Huanglong, Sichuan Natural Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace, Lhasa 1994, 2000, 2001 Lhasa, Tibet Cultural (Jokhang Temple, Norbulingka) Temple and Cemetery of Confucius and the 1994 Qufu, Shandong Cultural Kong Family Mansion Ancient Building Complex in the Wudang 1994 Shiyan, Hubei Cultural Mountains Chengde Mountain Resort and its Outlying 1994 Chengde, Hebei Cultural Temples in Chengde Mount Emei Scenic Area and Leshan Giant Cultural and 1996 Leshan, Sichuan Buddha Scenic Area Natural 1996 Lushan National Park Jiujiang, Jiangxi Cultural 1997 Old Town of Lijiang Lijiang, Yunan Cultural 1997 Ancient City of Pingyao Jinzhong, Shanxi Cultural Classic Gardens of Suzhou: Lion Grove, 1997, 2000 Humble Administrator Garden, Lingering Suzhou, Jiangsu Cultural Garden, Garden of Master of the Nets -

Tourists Preferences in Visiting Heritage Sites in China

Tourists Preferences in Visiting Heritage Sites in China Abdelhamid Jebbouri ( [email protected] ) Guangzhou University https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6065-0679 Heqing Zhang Guangzhou University Nasser Bouchiba SYSU: Sun Yat-Sen University Research article Keywords: tourism, Chinese cultural tourists, tourist preferences, China, heritage sites, GTPs Posted Date: June 25th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-626978/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/25 Abstract Tourism is a way of recreation, which involves a person’s travel to another city, country, and even to another continent. Travel is different, and any connoisseur can choose a vacation to their liking: active, educational, wellness, religious, beach, or rural. Tourism helps people escape from everyday problems, learn something new, and get an unforgettable aesthetic satisfaction. Also, such a vacation helps not only to learn the cultures of other countries and peoples but also contributes to the personal development of any traveller. In general, it allows people to combine relaxation with learning new things. However, different tourists have different preferences, so their motivation to visit specic cities, countries, or regions are also different. This study aims to provide tourists in China with an up to date and specic typology based on centricity and experience. Besides, the motive behind the work presented in this paper is to identify the different types of tourists in China, analyse their preferences, and as a result, create their holistic prole. Several studies from China already have information on the factors that inuence this typology. -

Chine D'exception : Huizhou-Fujian

CHINE D'EXCEPTION : HUIZHOU-FUJIAN 14 Jours / 11 Nuits - à partir de 2 534€ vols + hébergement + circuit Votre référence : p_CN_HUFU_ID3046 Un itinéraire hors des sentiers battus rythmé par une succession de contrastes qui révèlent une Chine inédite où modernité et traditions coexistent ; de la trépidante Shanghai aux villages du Huizhou historique, classés au patrimoine mondial par l’Unesco, aux paysages d'estampe du mont Huangshan, où plane le souvenir des poètes éminents ; des insolites villages-forteresses des Hakka, les « Tulou », aux « Diaolou », extravagantes tours de gardes du Guangdong. Vous aimerez ● Voyager en petit groupe limité à 16 personnes ● Les hébergements de charme à Wuyuan et Tangmo ● Admirer les paysages d'estampes du mont Huangshan ● Les magnifiques demeures de l'ancien Huizhou, fief des marchands lettrés ● Découvrir la vie traditionnelle des habitants des tulou, impressionnants villages-forteresses ● Arpenter la région de Kaiping et ses "diaolou", tours de garde d'inspirations chinoises et occidentales ● Pour les départs de mai et octobre, bénéficier de l'expertise d'un accompagnateur sinologue au départ de Paris qui vous fera partager sa connaissance approfondie du pays Jour 1 : DEPART POUR SHANGHAI Départ sur vol régulier. Jour 2 : SHANGHAI Arrivée à Shanghai. Premier regard sur le quartier de Pudong et ses édifices futuristes où se concentrent les plus beaux exemples d'architecture du XXIème siècle du haut de la tour de la Perle de l’Orient. Halte au musée du Passé consacré à l’histoire de Shanghai. Promenade sur le Bund d'où vous découvrirez un vaste panorama sur les deux rives du Huangpu et dans la rue de Nankin, artère très animée qui regroupe la plupart des activités commerciales et culturelles de la ville. -

Download PDF (Inglês)

http://dx.doi.org/10.21577/0100-4042.20170561 Quim. Nova, Vol. 43, No. 7, 884-890, 2020 CONTRIBUTION OF ENZYMATIC METHOD FOR ANALYZING SUCROSE AND STARCH IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE LIME- AND EARTH-BASED MORTARS Kun Zhanga,*, , Shiqiang Fangb, Xin Maoc and Bingjian Zhangb,d aSchool of Cultural Heritage, Northwest University, Xi’an, China bSchool of Arts and Archaeology, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China c Artigo Department of Chemistry, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore dDepartment of Chemistry, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China Recebido em 30/01/2020; aceito em 09/04/2020; publicado na web em 04/06/2020 Brown sugar and sticky rice were frequently used as organic additives in Chinese mortars. This study applied enzymatic spectrophotometric methods to identify sucrose and starch contents in traditional Chinese lime- and earth-based mortars. The focus was to understand and evaluate the qualitative detection capacity of enzymatic method in mortars, by first applying the method on a series of lab-prepared mortar specimens with specific amounts of brown sugar and sticky rice addition, then on historic mortar samples suspected to contain brown sugar and sticky rice. The potential contribution and limitations of enzymatic method in analysis of sucrose and starch in mortars was compared with other common available analytical methods. The results suggested that for lab-prepared brown sugar mortar specimens, enzymatic method was more sensitive and exclusive than chemical method, and particularly had higher detection capacity in lime mortars. For simulated mortars with sticky rice addition, enzymatic method showed no distinct detection capacity differences among the studied inorganic binders and comparing with chemical methods was more sensitive in earth-based mortars. -

![China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 [Online], Online Since 25 April 2007, Connection on 04 October 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3144/china-perspectives-66-july-august-2006-online-online-since-25-april-2007-connection-on-04-october-2020-5243144.webp)

China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 [Online], Online Since 25 April 2007, Connection on 04 October 2020

China Perspectives 66 | July- August 2006 Varia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/860 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.860 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2006 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 [Online], Online since 25 April 2007, connection on 04 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/860 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/chinaperspectives.860 This text was automatically generated on 4 October 2020. © All rights reserved 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Society The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) Buildings for dangerous times Patricia R.S. Batto Displacement From the Three Gorges Region A discreet arrival in the economic capital of China Florence PADOVANI Economy Family Entrepreneurship and Succession A survey in province of Zhejiang Yue Lin Law Is Taiwan a Presidential System? Ondrej Kucera History China-Taiwan: Young People Confront Their History Samia Ferhat Book reviews Cao Jinqing, China Along the Yellow River: Reflections on Rural Society New York, RoutledgeCurzon, 2005, 254 p. Claude Aubert Shi Li and Hiroshi Sato, Jingji zhuanxing de daijia (Unemployment, Inequality, and Poverty in Urban China) Beijing, China Financial Economics Publishing House, 2004, 4+413 p. Ying Chu Ng Mary Elizabeth Gallagher, Contagious Capitalism. Globalization and the Politics of Labor in China Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2005, 256 p. Jean-Louis Rocca China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 2 Hodong Kim, Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877 Stanford, California University Press, 2004, 295 p.