Global Art and Heritage Law Series China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection and Management Plan on Kaiping Diaolou and Villages

Name of project Protection and Management Plan on Kaiping Diaolou and Villages Entrusting party People's ~overnmentof Kaiping City, Guangdong Province Undertaking party Urban Planning and Design Center of Peking University Director of the center Professor Xie Ninggao Heads of Project Professor He Luping Dr. Shen Wenquan Preparer Wu Honglin, Chen Yaohua, Song Feng, Zheng Xinzhou, Han Xiangyi, Cao Lijuan, Xuhui, Jiang Piyan, Chen Rui Co-sponsors Kaiping Office of Protection and Management of Diaolou and Villages Land Administration Bureau of Kaiping Planning Burea of Kaiping Wuyi University Completion time December 2001 Contents I . Background of the planning 1.1 Background of the planning .....................................................1 1.2 Scope of the planning ........................................................... 2 . 1.3 Natural cond~t~ons............................................................... 2 1.4 Historical development .........................................................3 1.5 Socio-cconomic conditions .................................................... 3 11 . Analysis of property resources 2.1 Distribution of Kaiping Diaolou and Villages ...............................5 2.2 Description of the cultural heritage in the planned area ....................6 2.3 Spaces characteristics of the properties ...................................... I I 2.4 Value of the properties ......................................................... I3 111 . Current situation and analysis of the protection 3.1 Current situation of the -

Confucius & Shaolin Monastery

Guaranteed Departures • Tour Guide from Canada • Senior (60+) Discount C$50 • Early Bird Discount C$100 Highly Recommend (Confucius & Shaolin Monastery) (Tour No.CSSG) for China Cultural Tour Second Qingdao, Qufu, Confucius Temple, Mt. Taishan, Luoyang, Longmen Grottoes, Zhengzhou, Visit China Kaifeng, Shaolin Monastery 12 Days (10-Night) Deluxe Tour ( High Speed Train Experience ) Please be forewarned that the hour-long journey includes strenuous stair climbing. The energetic may choose to skip the cable car and conquer the entire 6000 steps on foot. Head back to your hotel for a Buffet Dinner. ( B / L / SD ) Hotel: Blossom Hotel Tai’an (5-star) Day 7 – Tai’an ~ Ji’nan ~ Luoyang (High Speed Train) After breakfast, we drive to Ji’nan, the “City of Springs” get ready to enjoy a tour of the “Best Spring of the World” Baotu Spring and Daming Lake. Then, after lunch, you will take a High-Speed Train to Luoyang, a city in He’nan province. You will be met by your local guide and transferred to your hotel. ( B / L / D ) Hotel: Luoyang Lee Royal Hotel Mudu (5-star) Day 8 – Luoyang ~ Shaolin Monastery ~ Zhengzhou Take a morning visit to Longmen Grottoes a UNESCO World Heritage site regarded as one of the three most famous treasure houses of stone inscriptions in China. Take a ride to Dengfeng (1.5 hour drive). Visit the famous Shaolin Monastery. The Pagoda Forest in Shaolin Temple was a concentration of tomb pagodas for eminent monks, abbots and ranking monks at the temple. You will enjoy world famous Chinese Shaolin Kung-fu Show afterwards. -

Cultural Factors in Tourism Interpretation of Leshan Giant Buddha

English Language Teaching; Vol. 10, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Cultural Factors in Tourism Interpretation of Leshan Giant Buddha Xiao Wenwen1 1 School of Foreign Languages, Leshan Normal University, Leshan, China Correspondence: Xiao Wenwen, School of Foreign Languages, Leshan Normal University, Leshan, Sichuan Province, China. Tel: 86-183-8334-0090. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 23, 2016 Accepted: December 17, 2016 Online Published: December 19, 2016 doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n1p56 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n1p56 Abstract Different cultural aspects are always involved in tourism interpretation, and the process of tourism interpretation is also cross-cultural communication. If the cultural factors can be interpreted for the foreign visitors in a better way, it’s beneficial to convey the cultural connotation of the scenic spot and it can be the communication more effective. There are many scenic spots in China, to show the beautiful scenery and traditional Chinese culture to the world. Leshan Giant Buddha is one of national 5A tourist attractions in Leshan, Sichuan Province, China, and there are a lot of tourists coming here every year, especially foreign tourists. Therefore, its tourism interpretation shall be better and better. The tourism interpretation of Leshan Giant Buddha concerns many cultural factors. Based on Skopostheorie, this paper discusses how to deal with the cultural factors in guide interpretation of Leshan Grand Buddha from the following three aspects: names of scenic spots, four-character phrases and classical Chinese poetry. Keywords: Leshan Giant Buddha, tourism interpretation, skopostheorie, cultural factors, methods 1. -

8/9Djiuzhaigou/Leshan/Mt.Emei Valuetour

8/9D JIUZHAIGOU/ LESHAN/ MT.EMEI VALUE TOUR Validity: 01 Jan – 31 Dec 2016 Tour Code: CHN-CTUC8 / CHN-CTUC9 Gourmet Delight: Sichuan local delights Sichuan Cuisine Herbal hotpot Leshan toufu feast Day 1: Singapore Chengdu (MOB) Assemble at Singapore Changi International Airport for your flight to Chengdu, the provincial capital of Sichuan. Day 2: Chengdu / Munigou Scenic Spot (Optional Itinerary) / Jiuzhaigou (B / L / D) After Breakfast, proceeds to Mounigou Scenic Area are a similar scenic and historic interest area as World Heritage Site Huanglong. The various sounds of waterfalls echo throughout the forest. Some fall down from the calcific steps while others pass through the woods creating an impressive spray and some misty fog. Day 3: Jiuzhaigou (Non Charter Coach) (B / L / D) After breakfast, head to Jiuzhaigou Scenic Area. Located 2000-4300 meters above sea level and characterized by its groups of lakes, waterfalls, snow-capped peaks, forests, it is known as “Earthly Paradise” and for its ever-changing seasonal landscapes. This primitive valley covers an area of 720 sq km. There are 118 green seas (mountain lakes), 12 groups of waterfalls, large amount of calcified flood plains and many endangered species. Jiuzhaigou is composed of three valleys arranged in a Y shape, which is Shuzheng Valley and Rize, Zechawa valleys. Main attraction: Arrow Bamboo Lake, Panda Lake, Long Lake, Sleeping Dragon Lake, Pearl Waterfalls, Nuorilang Waterfalls and so on. It was also recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992. In 2000, it was appraised as a national AAAAA scenic area, the highest accolade possible for a China tourist area. -

Study on the Influence of Tourists' Value on Sustainable Development of Huizhou Traditional Villages

E3S Web of Conferences 23 6 , 03007 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123603007 ICERSD 2020 Study on the Influence of Tourists’ Value on Sustainable Development of Huizhou Traditional Villages-- A Case of Hongcun and Xidi QI Wei 1, LI Mimi 2*, XIAO Honggen2, ZHANG Jinhe 3 1Anhui Technical College of Industry and Economy, Hefei, Anhui 2School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong 3School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Abstract: The tourists’ value of traditional village representing personal values, influences the tourists’ behavior deeply. This paper, with the soft ladder method of MEC theory from the perspective of the tourist, studies the value of tourists born in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s of the traditional villages in Hongcun and Xidi, which indicates 39 MEC value chains, and reveals 11 important attributes of Huizhou traditional villages, 16 tourism results, and 9 types of tourists’ values. With constructing a sustainable development model of Huizhou traditional villages based on tourists’ value, it shows an inherent interaction between tourists’ value and traditional village attributes subdividing the tourism products and marketing channels of Huizhou traditional villages, which is of great significance to the sustainable development of traditional villages in Huizhou. 1 Introduction connection between value and the attributes of traditional villages, to activate traditional village tourism Traditional villages refer to the rural communities, with and realize the sustainable development of traditional historical inheritance of certain ideology, culture, villages. customs, art and social-economic values, rural communities, formed by people with common values who gather together with agriculture as the basic content 2 Theoretical Basis of economic activities, including ancient villages, cultural historical villages, world heritage villages, 2.1 The Sustainable Development of Traditional etc.[1-3]. -

The Second Circular

The 24th World Congress of Philosophy Title: The XXIV World Congress of Philosophy (WCP2018) Date: August 13 (Monday) - August 20 (Monday) 2018 Venue: Peking University, Beijing, P. R. China Official Language: English, French, German, Spanish, Russian, Chinese Congress Website: wcp2018.pku.edu.cn Program: Plenary Sessions, Symposia, Endowed Lectures, 99 Sections for Contributed Papers, Round Tables, Invited Sessions, Society Sessions, Student Sessions and Poster Sessions Organizers: International Federation of Philosophical Societies Peking University CONFUCIUS Host: Chinese Organizing Committee of WCP 2018 Important Dates Paper Submission Deadline February 1, 2018 Proposal Submission Deadline February 1, 2018 Early Registration October 1, 2017 On-line Registration Closing June 30, 2018 On-line Hotel Reservation Closing August 6, 2018 Tour Reservation Closing June 30, 2018 * Papers and proposals may be accepted after that date at the discretion of the organizing committee. LAO TZE The 24th World Congress of Philosophy MENCIUS CHUANG TZE CONTENTS 04 Invitation 10 Organization 17 Program at a Glance 18 Program of the Congress 28 Official Opening Ceremony 28 Social and Cultural Events 28 Call for Papers 30 Call for Proposals WANG BI HUI-NENG 31 Registration 32 Way of Payment 32 Transportation 33 Accommodation 34 Tours Proposals 39 General Information CHU HSI WANG YANG-MING 02 03 The 24th World Congress of Philosophy Invitation WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT OF FISP Chinese philosophy represents a long, continuous tradition that has absorbed many elements from other cultures, including India. China has been in contact with the scientific traditions of Europe at least since the time of the Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), who resided at the Imperial court in Beijing. -

A Symbol of Global Protec- 7 1 5 4 5 10 10 17 5 4 8 4 7 1 1213 6 JAPAN 3 14 1 6 16 CHINA 33 2 6 18 AF Tion for the Heritage of All Humankind

4 T rom the vast plains of the Serengeti to historic cities such T 7 ICELAND as Vienna, Lima and Kyoto; from the prehistoric rock art 1 5 on the Iberian Peninsula to the Statue of Liberty; from the 2 8 Kasbah of Algiers to the Imperial Palace in Beijing — all 5 2 of these places, as varied as they are, have one thing in common. FINLAND O 3 All are World Heritage sites of outstanding cultural or natural 3 T 15 6 SWEDEN 13 4 value to humanity and are worthy of protection for future 1 5 1 1 14 T 24 NORWAY 11 2 20 generations to know and enjoy. 2 RUSSIAN 23 NIO M O UN IM D 1 R I 3 4 T A FEDERATION A L T • P 7 • W L 1 O 17 A 2 I 5 ESTONIA 6 R D L D N 7 O 7 H E M R 4 I E 3 T IN AG O 18 E • IM 8 PATR Key LATVIA 6 United Nations World 1 Cultural property The designations employed and the presentation 1 T Educational, Scientific and Heritage of material on this map do not imply the expres- 12 Cultural Organization Convention 1 Natural property 28 T sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of 14 10 1 1 22 DENMARK 9 LITHUANIA Mixed property (cultural and natural) 7 3 N UNESCO and National Geographic Society con- G 1 A UNITED 2 2 Transnational property cerning the legal status of any country, territory, 2 6 5 1 30 X BELARUS 1 city or area or of its authorities, or concerning 1 Property currently inscribed on the KINGDOM 4 1 the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

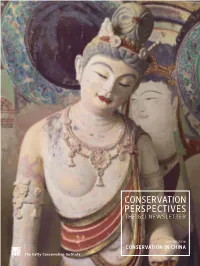

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Huangshan Hongcun Two Day Tour

! " # Guidebook $%&' Hefei Overview Hefei, capital of Anhui Province, is located in the middle part of China between the Yangtze River and the Huaihe River and beside Chaohu Lake. It occupies an area of 7,029 square kilometers of which the built-up urban area is 838.52 square kilometers. With a total population of about five million, the urban residents number about 2.7 million. As the provincial seat, the city is the political, economic, cultural, commercial and trade, transportation and information centre of Anhui Province as well as one of the important national scientific research and education bases. $% !() Hefei Attractions *+, The Memorial Temple Of Lord Bao The full name of this temple is the Memorial Temple of Lord Bao Xiaoshu. It was constructed in memory of Bao Zheng, who is idealized as an upright and honest official and a political reformer in the Song Dynasty. Xiaoshu is Lord Bao's posthumous name that was granted by Emperor Renzhong of the Song Dynasty in order to promote Lord Bao's contribution to the country. Former Residence of Li Hongzhang Lord Bao 1 -./01 Former Residence of Li Hongzhang Former Residence of Li Hongzhang is located on the Huaihe Road (the mid-section) in Hefei. It was built in the 28th year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu of the Qing Dynasty. The entire building looks magnificent with carved beams and rafters. It is the largest existing and best preserved former residence of a VIP in Hefei and is a key cultural relic site under the protection of Anhui Provincial Government. -

Study on the Coniferous Characters of Pinus Yunnanensis and Its Clustering Analysis

Journal of Polymer Science and Engineering (2017) Original Research Article Study on the Coniferous Characters of Pinus yunnanensis and Its Clustering Analysis Zongwei Zhou,Mingyu Wang,Haikun Zhao Huangshan Institute of Botany, Anhui Province, China ABSTRACT Pine is a relatively easy genus for intermediate hybridization. It has been widely believed that there should be a natural hybrid population in the distribution of Pinus massoniona Lamb. and Pinus hangshuanensis Hsia, that is, the excessive type of external form between Pinus massoniana and Pinus taiwanensis exist. This paper mainly discusses the traits and clustering analysis of coniferous lozeng in Huangshan scenic area. This study will provide a theoretical basis for the classification of long and outstanding Huangshan Song and so on. At the same time, it will provide reference for the phenomenon of gene seepage between the two species. KEYWORDS: Pinus taiwanensis Pinus massoniana coniferous seepage clustering Citation: Zhou ZW, Wang MY, ZhaoHK, et al. Study on the Coniferous Characters of Pinus yunnanensis and Its Clustering Analysis, Gene Science and Engineering (2017); 1(1): 19–27. *Correspondence to: Haikun Zhao, Huangshan Institute of Botany, Anhui Province, China, [email protected]. 1. Introduction 1.1. Research background Huangshan Song distribution in eastern China’s subtropical high mountains, more than 700m above sea level. Masson pine is widely distributed in the subtropical regions of China, at the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, vertically distributed below 700m above sea level, the upper reaches of the Yangtze River area, the vertical height of up to 1200 - 1500m or so. In the area of Huangshan Song and Pinus massoniana, an overlapping area of Huangshan Song and Pinus massoniana was formed between 700 - 1000m above sea level. -

China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 the Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) 2

China Perspectives 66 | July- August 2006 Varia The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) Buildings for dangerous times Patricia R.S. Batto Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1033 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1033 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2006 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Patricia R.S. Batto, « The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) », China Perspectives [Online], 66 | July- August 2006, Online since 01 June 2007, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1033 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1033 This text was automatically generated on 28 October 2019. © All rights reserved The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) 1 The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) Buildings for dangerous times Patricia R.S. Batto EDITOR'S NOTE Translated from the French original by Jonathan Hall I would particularly like to thank Annie Au-Yeung for her valuable help in preparing this article. 1 To the west of the Pearl River Delta, in villages nestling amid green bamboo and banana groves and surrounded by a patchwork of rice paddies, stand a number of incongruous dark towers bristling with battlements, fearsome fortresses full of arrow slits, and even the occasional elegant turret above an ornate mansion. All these buildings, in the middle of the Chinese countryside, look like faint reflections of a distant West. How did they end up on the banks of the Kaiping rice paddies? 2 Kaiping is situated in south-western Guangdong and, according to official figures, has 1,833 of these buildings or diaolou1, most of which were built in the early twentieth century. -

IMAGES of POWER: BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE (Buddhism on the Silk Road) BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE on the Silk Road

IMAGES OF POWER: BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE (Buddhism on the Silk Road) BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE on the Silk Road Online Links: Bamiyan Buddhas: Should they be rebuit? – BBC Afghanistan Taliban Muslims destroying Bamiyan Buddha Statues – YouTube Bamiyan Valley Cultural Remains – UNESCO Why the Taliban are destroying Buddhas - USA Today 1970s Visit to Bamiyan - Smithsonian Video Searching for Buddha in Afghanistan – Smithsonian Seated Buddha from Gandhara - BBC History of the World BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE of China Online Links: Longmen Caves - Wikipedia Longmen Grottoes – Unesco China The Longmen Caves – YouTube Longmen Grottoes – YouTube Lonely Planet's Best In China - Longmen China – YouTube Gandhara Buddha - NGV in Australia Meditating Buddha, from Gandhara , second century CE, gray schist The kingdom of Gandhara, located in the region of presentday northern Pakistan and Afghanistan, was part of the Kushan Empire. It was located near overland trade routes and links to the ports on the Arabian Sea and consequently its art incorporated Indian, Persian and Greco- Roman styles. The latter style, brought to Central Asia by Alexander the Great (327/26–325/24 BCE) during his conquest of the region, particularly influenced the art of Gandhara. This stylistic influence is evident in facial features, curly hair and classical style costumes seen in images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas that recall sculptures of Apollo, Athena and other GaecoRoman gods. A second-century CE statue carved in gray schist, a local stone, shows the Buddha, with halo, ushnisha, urna, dressed in a monk’s robe, seated in a cross-legged yogic posture similar to that of the male figure with horned headdress on the Indus seal.