Architecture, Space, and Society in Chinese Villages, 1978-2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection and Management Plan on Kaiping Diaolou and Villages

Name of project Protection and Management Plan on Kaiping Diaolou and Villages Entrusting party People's ~overnmentof Kaiping City, Guangdong Province Undertaking party Urban Planning and Design Center of Peking University Director of the center Professor Xie Ninggao Heads of Project Professor He Luping Dr. Shen Wenquan Preparer Wu Honglin, Chen Yaohua, Song Feng, Zheng Xinzhou, Han Xiangyi, Cao Lijuan, Xuhui, Jiang Piyan, Chen Rui Co-sponsors Kaiping Office of Protection and Management of Diaolou and Villages Land Administration Bureau of Kaiping Planning Burea of Kaiping Wuyi University Completion time December 2001 Contents I . Background of the planning 1.1 Background of the planning .....................................................1 1.2 Scope of the planning ........................................................... 2 . 1.3 Natural cond~t~ons............................................................... 2 1.4 Historical development .........................................................3 1.5 Socio-cconomic conditions .................................................... 3 11 . Analysis of property resources 2.1 Distribution of Kaiping Diaolou and Villages ...............................5 2.2 Description of the cultural heritage in the planned area ....................6 2.3 Spaces characteristics of the properties ...................................... I I 2.4 Value of the properties ......................................................... I3 111 . Current situation and analysis of the protection 3.1 Current situation of the -

To Search High and Low: Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, and China's

Scapegoat Architecture/Landscape/Political Economy Issue 03 Realism 30 To Search High and Low: Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, and China’s Architectural Historiography, 1932–1946 by Zhu Tao MISSING COMPONENTS Living in the remote countryside of Southwest Liang and Lin’s historiographical construction China, they had to cope with the severe lack of was problematic in two respects. First, they were financial support and access to transportation. so eager to portray China’s traditional architec- Also, there were very few buildings constructed ture as one singular system, as important as the in accordance with the royal standard. Liang and Greek, Roman and Gothic were in the West, that his colleagues had no other choice but to closely they highly generalized the concept of Chinese study the humble buildings in which they resided, architecture. In their account, only one dominant or others nearby. For example, Liu Zhiping, an architectural style could best represent China’s assistant of Liang, measured the courtyard house “national style:” the official timber structure exem- he inhabited in Kunming. In 1944, he published a plified by the Northern Chinese royal palaces and thorough report in the Bulletin, which was the first Buddhist temples, especially the ones built during essay on China’s vernacular housing ever written the period from the Tang to Jin dynasties. As a by a member of the Society for Research in Chi- consequence of their idealization, the diversity of nese Architecture.6 Liu Dunzhen, director of the China’s architectural culture—the multiple con- Society’s Literature Study Department and one of struction systems and building types, and in par- Liang’s colleagues, measured his parents’ country- ticular, the vernacular buildings of different regions side home, “Liu Residence” in Hunan province, in and ethnic groups—was roundly dismissed. -

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü Duo 女鐸, 1912–1951

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü duo 女鐸, 1912–1951 Zhou Yun A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University February 2019 © Copyright by Zhou Yun 2019 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Benjamin Penny for his valuable suggestions and constant patience throughout my five years at The Australian National University (ANU). His invitation to study for a Doctorate at Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) not only made this project possible but also kindled my academic pursuit of the history of Christianity. Coming from a research background of contemporary Christian movements among diaspora Chinese, I realise that an appreciation of the present cannot be fully achieved without a thorough study of the past. I was very grateful to be given the opportunity to research the Republican era and in particular the development of Christianity among Chinese women. I wish to thank my two co-advisers—Dr. Wei Shuge and Dr. Zhu Yujie—for their time and guidance. Shuge’s advice has been especially helpful in the development of my thesis. Her honest critiques and insightful suggestions demonstrated how to conduct conscientious scholarship. I would also like to extend my thanks to friends and colleagues who helped me with my research in various ways. Special thanks to Dr. Caroline Stevenson for her great proof reading skills and Dr. Paul Farrelly for his time in checking the revised parts of my thesis. -

Natural History Connects Medical Concepts and Painting Theories In

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Natural history connects medical concepts and painting theories in China Sara Madeleine Henderson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Henderson, Sara Madeleine, "Natural history connects medical concepts and painting theories in China" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 1932. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1932 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATURAL HISTORY CONNECTS MEDICAL CONCEPTS AND PAINTING THEORIES IN CHINA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Sara Madeleine Henderson B.A., Smith College, 2001 August 2007 Dedicated to Aunt Jan. Janice Rubenstein Sachse, 1908 - 1998 ii Preface When I was three years old my great-aunt, Janice Rubenstein Sachse, told me that I was an artist. I believed her then and since, I have enjoyed pursuing that goal. She taught me the basics of seeing lines in nature; lines formed on the contact of shadow and light, as well as organic shapes. We also practiced blind contour drawing1. I took this exercise very seriously then, and I have reflected upon these moments of observation as I write this paper. -

Selena K. Anders

CURRICULUM VITAE SELENA K. ANDERS Via Ostilia, 15 Rome, Italy 00184 +39 334 582-4183 [email protected] Education “La Sapienza” University of Rome, Ph.D.; Rome, Italy Department of Architecture-Theory and Practice, December 2016 under the supervision of Antonino Saggio and Simona Salvo University of Notre Dame, M.Arch; Notre Dame, Indiana School of Architecture, cum laude May 2009. Archeworks, Postgraduate Certificate; Chicago, Illinois Social and Environmental Urban Design, May 2006. DePaul University, B.A.; Chicago Illinois Art History and Anthropology, Minor in Italian Language and Literature, magna cum laude, June 2005. Academic Positions Assistant Professor, School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame 2016-Present Co-Director China Summer Study Program, School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame 2010-Present Faculty, Office of Pre-College Programs, University of Notre Dame Rome: History, Culture, and Experience, 2015 Co-Director and Co-Founder of HUE/ND (Historic Urban Environments Notre Dame) School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame, 2014-Present Projects: Cities in Text: Rome Associate Director and Co-Founder of DHARMA LAB (Digital Historic Architectural Research and Material Analysis), School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame, 2006-Present India: Documentation of Mughal Tombs in Agra, India Italy: Documentation of the Roman Forum in Rome, Italy Vatican City: Belvedere Court Professor of the Practice, School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame, 2012-Present Faculty, Career Discovery for High School -

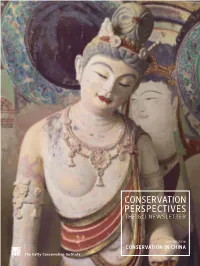

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Ni Zan in Oxford Art Online

Ni Zan in Oxford Art Online http://www.oxfordartonline.com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/subs... Oxford Art Online Grove Art Online Ni Zan article url: http://www.oxfordartonline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/art/T062602 Ni Zan [Ni Tsan; zi Yuanzhen; hao Yunlin] (b Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, 1301; d 1374). Chinese painter and calligrapher. He is designated one of the Four Masters of the Yuan (1279–1368), with HUANG GONGWANG, WU ZHEN and WANG MENG. Ni Zan’s family were of Xixia (Tangut) origin. His tenth-generation ancestor Shi came to China as Xixia ambassador in 1034–7 at the time of Emperor Renzong (reg 1023–63), and the family settled in Duliang (modern Anhui Province). In 1127–30, under Emperor Gaozong (reg 1127–62), Ni Zan’s fifth-generation ancestor Yi moved south with the Southern Song (1127–1279), settling at Zhituo village in Wuxi, modern Jiangsu Province, where the Ni family prospered. Ni Zan and his elder brother Ying were the sons of a concubine, Yan. Their father died when they were young, and they were raised by their eldest half-brother, Ni Zhaogui (1279–1328). Ying was mentally incompetent, and after Zhaogui’s death Ni Zan assumed responsibility for the family estate, a role ill-suited to his natural inclinations. He led a privileged and secluded home life for 20 or more years; in the mid-1340s he spent most of his time among rare books, antique paintings, calligraphy and flowers in his favourite studio, the Qingbi ge (‘Pure and secluded pavilion’). Ni Zan was an ardent admirer of the great Northern Song (1127–1279) artist and connoisseur, MI FU, and shared two of his idiosyncrasies: fastidiousness and generosity. -

China Perspectives, 66 | July- August 2006 the Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) 2

China Perspectives 66 | July- August 2006 Varia The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) Buildings for dangerous times Patricia R.S. Batto Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1033 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1033 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2006 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Patricia R.S. Batto, « The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) », China Perspectives [Online], 66 | July- August 2006, Online since 01 June 2007, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1033 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1033 This text was automatically generated on 28 October 2019. © All rights reserved The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) 1 The Diaolou of Kaiping (1842-1937) Buildings for dangerous times Patricia R.S. Batto EDITOR'S NOTE Translated from the French original by Jonathan Hall I would particularly like to thank Annie Au-Yeung for her valuable help in preparing this article. 1 To the west of the Pearl River Delta, in villages nestling amid green bamboo and banana groves and surrounded by a patchwork of rice paddies, stand a number of incongruous dark towers bristling with battlements, fearsome fortresses full of arrow slits, and even the occasional elegant turret above an ornate mansion. All these buildings, in the middle of the Chinese countryside, look like faint reflections of a distant West. How did they end up on the banks of the Kaiping rice paddies? 2 Kaiping is situated in south-western Guangdong and, according to official figures, has 1,833 of these buildings or diaolou1, most of which were built in the early twentieth century. -

An Ancient Mosque in Ningbo, China “Historical and Architectural Study”

JOURNAL OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE P-ISSN: 2086-2636 E-ISSN: 2356-4644 Journal Home Page: http://ejournal.uin-malang.ac.id/index.php/JIA AN ANCIENT MOSQUE IN NINGBO, CHINA “HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL STUDY” |Received December 13th 2016 | Accepted April 4th 2017| Available online June 15th 2017| | DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.18860/jia.v4i3.3851 | Hamada M. Hagras ABSTRACT Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt With the rise of Tang dynasty (618–907), Ningbo was an important [email protected] commercial city on the Chinese eastern coast. Arab merchants had an important role in trade relations between China and the West. Ningbo mosque was initially built in 1003 during Northern Song period by Muslims traders who had migrated from Arab lands to settle in China. Through ongoing research of representative Muslim architecture, such as Chinese Mosques, this paper seeks to shed light on the artistic features of this mosque. Many of the key characteristics of this distinctive ethnic heritage are based on commonly held religious beliefs and on the relationship between culture and religion. This paper aims to study the characteristics of Chinese mosques architecture, through studying one of the most important planning patterns of the traditional courtyards plan Known as Siheyuan, and it will also make a practical study on Ningbo Yuehu Mosque. The result of this study shows that the Ningbo Yuehu mosque is like Chinese mosques which follows essentially the norms of Chinese planning, layout design, and wooden structures. KEYWORDS: Ningbo, Mosque, Plan, Courtyard, Inscriptions INTRODUCTION (626‐649) received an embassy from the last Sassanid rulers Yazdegerd III (631‐651) asking for help against WHY THE SELECTED NINGBO MOSQUE? the invading Arab armies of his country, however, the emperor avoid to help him to ward off problems that Although many Chinese cities contain more may result from it [8][9]. -

The Chinese Liberal Camp in Post-June 4Th China

The Chinese Liberal Camp [/) OJ > been a transition to and consolidation of "power elite capital that economic development necessitated further reforms, the in Post-June 4th China ism" (quangui zibenzhuyr), in which the development of the provocative attacks on liberalism by the new left, awareness of cruellest version of capitalism is dominated by the the accelerating pace of globalisation, and the posture of Jiang ~ Communist bureaucracy, leading to phenomenal economic Zemin's leadership in respect to human rights and rule of law, OJ growth on the one hand and endemic corruption, striking as shown by the political report of the Fifteenth Party []_ social inequalities, ecological degeneration, and skilful politi Congress and the signing of the "International Covenant on D... cal oppression on the other. This unexpected outcome has Economic, Social and Cultural Rights" and the "International This paper is aa assessment of Chinese liberal intellectuals in the two decades following June 4th. It provides an disheartened many democracy supporters, who worry that Covenant on Civil and Political Rights."'"' analysis of the intellectual development of Chinese liberal intellectuals; their attitudes toward the party-state, China's transition is "trapped" in a "resilient authoritarian The core of the emerging liberal camp is a group of middle economic reform, and globalisation; their political endeavours; and their contributions to the project of ism" that can be maintained for the foreseeable future. (3) age scholars who can be largely identified as members of the constitutional democracy in China. However, because it has produced unmanageably acute "Cultural Revolution Generation," including Zhu Xueqin, social tensions and new social and political forces that chal Xu Youyu, Qin Hui, He Weifang, Liu junning, Zhang lenge the one-party dictatorship, Market-Leninism is not actu Boshu, Sun Liping, Zhou Qiren, Wang Dingding and iberals in contemporary China understand liberalism end to the healthy trend of politicalliberalisation inspired by ally that resilient. -

Foucault, Laclau, Habermas

CULTURE – SOCIETY – EDUCATION NO. 2 (12) 2017 POZNAN Lotar Rasiński Dolnośląska Szkoła Wyższa we Wrocławiu Three concepts of discourse: Foucault, Laclau, Habermas KEYWORDS ABSTRACT Michel Foucault, Ernesto The aim of this article is to examine three currently dominant con- Laclau, Jürgen Habermas, cepts of discourse, developed by Michel Foucault, Ernesto Laclau and discourse, theory of lan- Jürgen Habermas. I argue that these concepts of discourse constitute guage, linguistic turn neither a coherent methodological agenda nor a coherent theoretical vision. That means that the reference to discourse will always imply engaging with a particular theoretical framework. I briefly discuss the theoretical traditions from which these concepts emerged and point to the essential elements which the respective concepts of discourse derived from these traditions. Concluding, I examine differences be- tween and similarities in the discussed concepts, whereby I address, in particular, the relationship between discourse and everyday lan- guage, the notion of subjectivity and the concept of the social world. Adam Mickiewicz University Press, pp. 33-50 ISSN 2300-0422. DOI 10.14746/kse.2017.12.2. The aim of this article is to examine three currently dominant concepts of discourse developed by Michel Foucault, Ernesto Laclau and Jürgen Habermas. I purpose- fully relinquish the term “theory of discourse” as at the core of my argument is the idea that such a theory is, in fact, non-existent. An essential challenge that social sciences scholars who use discourse analysis face is locating their own research in a broader methodological framework in which a particular concept of discourse was formulated. As a result, theoretical choices involved in research, such as, for example, the notion of subjectivity, the concept of the social world and the rela- tionship between discourse and everyday language, are essentially influenced by this framework. -

Parrhesia 31 · 2019 Parrhesia 31 · 2019 · 1-16

parrhesia 31 · 2019 parrhesia 31 · 2019 · 1-16 gaston bachelard and contemporary philosophy massimiliano simons, jonas rutgeerts, anneleen masschelein and paul cortois1 There are philosophers whose name sounds familiar, but who very few people know in more than a vague sense. And there are philosophers whose footprints are all over the recent history of philosophy, but who themselves have retreated somewhat in the background. Gaston Bachelard (1884-1962) is a bit of both. With- out doubt, he was one of the most prominent French philosophers in the first half of the 20th century, who wrote over twenty books, covering domains as diverse as philosophy of science, poetry, art and metaphysics. His ideas profoundly influ- enced a wide array of authors including Georges Canguilhem, Gilbert Simondon, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Bruno Latour and Pierre Bourdieu. Up until the 1980s, Bachelard’s work was widely read by philosophers, scientists, literary theo- rists, artists, and even wider audiences and in his public appearances he incar- nated one of the most iconic and fascinating icons of a philosopher. And yet, surprisingly, in recent years the interest in Bachelard’s theoretical oeuvre seems to have somewhat waned. Apart from some recent attempts to revive his thinking, the philosopher’s oeuvre is rarely discussed outside specialist circles, often only available for those able to read French.2 In contemporary Anglo-Saxon philosophy the legacy of Bachelard seems to consist mainly in his widely known book Poetics of Space. While some of Bachelard’s contemporaries, like Georges Canguilhem or Gilbert Simondon (see Parrhesia, issue 7), who were profoundly influenced by Bachelard, have been rediscovered, the same has not happened for Bachelard’s philosophical oeuvre.