4 Towards the Definition of a Muslim in an Islamic State: the Case of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Varieties of South Asian Islam Francis Robinson Research Paper No.8

Varieties of South Asian Islam Francis Robinson Research Paper No.8 Centre for Research September 1988 in Ethnic Relations University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7Al Francis Robinson is a Reader in History at the Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, University of London. For the past twenty years he has worked on Muslim politics and Islamic institutions in South Asia and is the author of many articles relating to these fields. His main books are: Separatism Among Indian Muslims: The Politics of the United Provinces' Muslims 1860-1923 (Cambridge, 1974); Atlas of the Islamic World since 1500 (Oxford, 1982); Islam in Modern South Asia (Cambridge, forthcoming); Islamic leadership in South Asia: The 'Ulama of Farangi Mahall from the seventeenth to the twentieth century (Cambridge, forthcoming). Varieties of South Asian Islam1 Over the past forty years Islamic movements and groups of South Asian origin have come to be established in Britain. They offer different ways, although not always markedly different ways, of being Muslim. Their relationships with each other are often extremely abrasive. Moreover, they can have significantly different attitudes to the state, in particular the non-Muslim state. An understanding of the origins and Islamic orientations of these movements and groups would seem to be of value in trying to make sense of their behaviour in British society. This paper will examine the following movements: the Deobandi, the Barelvi, the Ahl-i Hadith, the Tablighi Jamaat, the Jamaat-i Islami, the Ahmadiyya, and one which is unlikely to be distinguished in Britain by any particular name, but which represents a very important Islamic orientation, which we shall term the Modernist.2 It will also examine the following groups: Shias and Ismailis. -

Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: a Study Of

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 5 Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud Abstract Pakistan’s successive constitutions, which enumerate guaranteed fundamental rights and pro- vide for the separation of state power and judicial review, contemplate judicial protection of vul- nerable sections of society against unlawful executive and legislative actions. This Article focuses upon the remarkably divergent pronouncements of Pakistan’s judiciary regarding the religious status and freedom of religion of one particular religious minority, the Ahmadis. The superior judiciary of Pakistan has visited the issue of religious freedom for the Ahmadis repeatedly since the establishment of the State, each time with a different result. The point of departure for this ex- amination is furnished by the recent pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (”Supreme Court” or “Court”) in Zaheeruddin v. State,’ wherein the Court decided that Ordinance XX of 1984 (”Ordinance XX” or ”Ordinance”), which amended Pakistan’s Penal Code to make the public prac- tice by the Ahmadis of their religion a crime, does not violate freedom of religion as mandated by the Pakistan Constitution. This Article argues that Zaheeruddin is at an impermissible variance with the implied covenant of freedom of religion between religious minorities and the Founding Fathers of Pakistan, the foundational constitutional jurisprudence of the country, and the dictates of international human rights law. -

Pakistan: Massacre of Minority Ahmadis | Human Rights Watch

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH http://www.hrw.org Pakistan: Massacre of Minority Ahmadis Attack on Hospital Treating Victims Shows How State Inaction Emboldens Extremists The mosque attacks and the June 1, 2010 subsequent attack on the hospital, amid rising sectarian violence, (New York) – Pakistan’s federal and provincial governments should take immediate legal action underscore the vulnerability of the against Islamist extremist groups responsible for threats and violence against the minority Ahmadiyya Ahmadi community. religious community, Human Rights Watch said today. Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher On May 28, 2010, extremist Islamist militants attacked two Ahmadiyya mosques in the central Pakistani city of Lahore with guns, grenades, and suicide bombs, killing 94 people and injuring well over a hundred. Twenty-seven people were killed at the Baitul Nur Mosque in the Model Town area of Lahore; 67 were killed at the Darul Zikr mosque in the suburb of Garhi Shahu. The Punjabi Taliban, a local affiliate of the Pakistani Taliban, called the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), claimed responsibility. On the night of May 31, unidentified gunmen attacked the Intensive Care Unit of Lahore’s Jinnah Hospital, where victims and one of the alleged attackers in Friday's attacks were under treatment, sparking a shootout in which at least a further 12 people, mostly police officers and hospital staff, were killed. The assailants succeeded in escaping. “The mosque attacks and the subsequent attack on the hospital, amid rising sectarian violence, underscore the vulnerability of the Ahmadi community,” said Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. -

A Tale of Two Ahmadiyya Mosques… 51 Even Take Place Thousands of Miles Away, but Their Effects Can Still Be Felt Locally

49 TALE OF TWO AHMADIYYA A MOSQUES: RELIGION, ETHNIC POLITICS, AND URBAN PLANNING IN LONDON Marzia Balzani Laboratorium. 2015. 7(3):49–71 Laboratorium. 2015. © Marzia Balzani is Research Professor of Anthropology in the Division of Arts and Humanities, New York University Abu Dhabi. Address for correspondence: New York University Abu Dhabi, PO Box 129188, Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. [email protected]. I wish to thank Grazyna Kubica-Heller and Agnieszka Pasieka, the organizers of the 2014 European Association of Social Anthropologists conference panel “Post- Industrial Revolution? Changes and Continuities within Urban Landscapes,” where an earlier version of this paper was first presented. I also thank Shamoon Zamir for his generous advice and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments. Built on the site of a disused dairy in London, the Ahmadiyya Baitul Futuh Mosque is simultaneously a regenerated postindustrial site, a signal achievement for the commu- nity that built it, an affront to local Sunni Muslims, a focus for Islamophobic protest, and a boost to local regeneration plans and tourism. Using town planning documents, media articles, and ethnographic fieldwork, this article considers the conflicting dis- courses available to locals, Muslim and non-Muslim, centered on the new Baitul Futuh Mosque and an older, smaller, suburban Ahmadiyya mosque located nearby. These dis- courses are situated in the broader transnational context of sectarian violence and cre- ation of community where ethnicity, faith, and immigration status mark those who at- tend the mosques. The article considers the different historical periods in which the two mosques were built, the class composition of residents in the neighborhoods of the mosques, and the consequences these have for how the mosques are incorporated into the locality. -

View a List of Publications

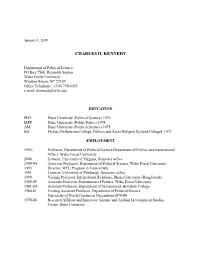

January 1, 2019 CHARLES H. KENNEDY Department of Political Science PO Box 7568, Reynolda Station Wake Forest University Winston-Salem, NC 27109 Office Telephone: (336) 758-5453 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION PhD Duke University (Political Science) 1979 MPP Duke University (Public Policy) 1978 AM Duke University (Political Science) 1975 BA Florida Presbyterian College, Politics and Asian Religion [Eckerd College], 1973 EMPLOYMENT 1994- Professor, Department of Political Science/Department of Politics and International Affairs, Wake Forest University 2006 Lecturer, University of Virginia, Semester at Sea 1989-94 Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Wake Forest University 1993 Director, WFU Program in Venice Italy 1991 Lecturer, University of Pittsburgh, Semester at Sea 1990 Visiting Professor, International Relations, Dhaka University (Bangladesh) 1985-89 Assistant Professor, Department of Politics, Wake Forest University 1981-84 Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Bowdoin College 1980-81 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of North Carolina at Greensboro1979-80 1978-80 Research Affiliate and Instructor, Islamic and Arabian Development Studies Center, Duke University COURSES TAUGHT AT WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY (1985-2017) PS 114 - Introduction to Comparative Politics PS 116 - Introduction to International Politics PS 219 - Policy Analysis PS 234 - Politics of Japan and the PRC PS 245/MLS 479 - Ethnonationalism PS 246 - Politics and Policy in South Asia PS 247/MLS 482 - Islam -

Germany Jalsa Tour 2017

HUZOOR’S TOUR OF GERMANY 2017 AUGUST 2017 A Personal Account Part 1 By Abid Khan 1 Introduction On Saturday, 19 August 2017, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih V (aba) departed from London for a 10-day tour to Germany, during which he would grace the Germany Jalsa with his presence. Apart from Khala Saboohi (Huzoor’s respected wife), there were 17 members of Qafila who travelled with Huzoor from London that day. There were six security staff – Muhammad Ahmad, Nasir Saeed, Sakhawat Bajwa, Mahmood Khan, Abdul Qadous Khawaja and Mohsin Awan. The office staff comprised Munir Ahmed Javed (Private Secretary), Abdul Majid Tahir (Additional Wakil-ul-Tabshir), Hamad Mobeen (PS Office) and me travelling on behalf of the central Press & Media Office. Graciously, Huzoor permitted three students of Jamia Ahmadiyya to accompany him on this tour. These were Masshud Khan from UK Jamia and Arsalan Warraich and Farrukh Rehman Tahir from Canada Jamia. Nadeem Amini, Nasir Amini, Dr. Momin Jadran and Abdul Rehman were also part of Huzoor’s Qafila. They had each volunteered to drive their personal cars as Qafila cars and Huzoor had graciously accepted their request. Departure from Masjid Fazl I arrived at the Fazl Mosque at 9.15am and gave in my luggage. I found out I would be sitting in Nadeem Amini’s car, along with Sakhawat Bajwa sahib and Khawaja Qudoos sahib. I was happy to have this news, as on previous 2 occasions when we had sat together we had enjoyed each other’s company and the long car journeys seemed to go by much quicker. -

In the Northern Areas, Pakistan Nosheen Ali Aga Khan University, [email protected]

eCommons@AKU Institute for Educational Development, Karachi Institute for Educational Development January 2008 Outrageous state, sectarianized citizens: Deconstructing the ‘Textbook Controversy’ in the Northern Areas, Pakistan Nosheen Ali Aga Khan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_ied_pdck Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Other Education Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Ali, N. (2008). Outrageous state, sectarianized citizens: Deconstructing the “Textbook Controversy” in the Northern Areas, Pakistan. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 2, 1–21. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 2 | 2008 ‘Outraged Communities’ Outrageous State, Sectarianized Citizens: Deconstructing the ‘Textbook Controversy’ in the Northern Areas, Pakistan Nosheen Ali Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic version URL: http://samaj.revues.org/1172 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.1172 ISSN: 1960-6060 Electronic reference Nosheen Ali, « Outrageous State, Sectarianized Citizens: Deconstructing the ‘Textbook Controversy’ in the Northern Areas, Pakistan », South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], 2 | 2008, Online since 31 December 2008, connection on 30 September 2016. URL : http://samaj.revues.org/1172 ; DOI : 10.4000/samaj.1172 This text was automatically generated on 30 septembre 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Outrageous State, Sectarianized Citizens:Deconstructing the ‘Textbook Controv... 1 Outrageous State, Sectarianized Citizens: Deconstructing the ‘Textbook Controversy’ in the Northern Areas, Pakistan Nosheen Ali Introduction 1 In May 2000, the Shia Muslims1 based in the Gilgit district of the Northern Areas began to agitate against the recently changed curriculum of government schools in the region. -

Pakistan, the Deoband ‘Ulama and the Biopolitics of Islam

THE METACOLONIAL STATE: PAKISTAN, THE DEOBAND ‘ULAMA AND THE BIOPOLITICS OF ISLAM by Najeeb A. Jan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Juan R. Cole, Co-Chair Professor Nicholas B. Dirks, Co-Chair, Columbia University Professor Alexander D. Knysh Professor Barbara D. Metcalf HAUNTOLOGY © Najeeb A. Jan DEDICATION Dedicated to my beautiful mother Yasmin Jan and the beloved memory of my father Brian Habib Ahmed Jan ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to whom I owe my deepest gratitude for bringing me to this stage and for shaping the world of possibilities. Ones access to a space of thought is possible only because of the examples and paths laid by the other. I must begin by thanking my dissertation committee: my co-chairs Juan Cole and Nicholas Dirks, for their intellectual leadership, scholarly example and incredible patience and faith. Nick’s seminar on South Asia and his formative role in Culture/History/Power (CSST) program at the University of Michigan were vital in setting the critical and interdisciplinary tone of this project. Juan’s masterful and prolific knowledge of West Asian histories, languages and cultures made him the perfect mentor. I deeply appreciate the intellectual freedom and encouragement they have consistently bestowed over the years. Alexander Knysh for his inspiring work on Ibn ‘Arabi, and for facilitating several early opportunity for teaching my own courses in Islamic Studies. And of course my deepest thanks to Barbara Metcalf for unknowingly inspiring this project, for her crucial and sympathetic work on the Deoband ‘Ulama and for her generous insights and critique. -

Ahmadiyya Islam and the Muslim Diaspora

Ahmadiyya Islam and the Muslim Diaspora This book is a study of the UK-based Ahmadiyya Muslim community in the context of the twentieth-century South Asian diaspora. Originating in late nineteenth-century Punjab, the Ahmadis are today a vibrant international religious movement; they are also a group that has been declared heretic by other Muslims and one that continues to face persecution in Pakistan, the country the Ahmadis made their home after the partition of India in 1947. Structured as a series of case studies, the book focuses on the ways in which the Ahmadis balance the demands of faith, community and modern life in the diaspora. Following an overview of the history and beliefs of the Ahmadis, the chapters examine in turn the use of ceremonial occasions to consolidate a diverse international community; the paradoxical survival of the enchantments of dreams and charisma within the structures of an institutional bureaucracy; asylum claims and the ways in which the plight of asylum seekers has been strategically deployed to position the Ahmadis on the UK political stage; and how the planning and building of mosques serves to establish a home within the diaspora. Based on fieldwork conducted over several years in a range of formal and informal contexts, this timely book will be of interest to an interdisciplinary audience from social and cultural anthropology, South Asian studies, the study of Islam and of Muslims in Europe, refugee, asylum and diaspora studies, as well as more generally religious studies and history. Marzia Balzani is Research Professor of Anthropology at New York University Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. -

Huzoor's Tour of the United States and Guatemala

HUZOOR’S TOUR OF THE UNITED STATES AND GUATEMALA OCTOBER – NOVEMBER 2018 Part 4 A Personal Account By Abid Khan 1 Introduction Part 3 of this series of diaries ended with Huzoor’s meetings with Ambassador Sam Brownback and Congressman Jamie Raskin at Baitur Rahman. This diary, part 4, commences immediately thereafter and in this concluding part, I shall mention aspects of Huzoor’s engagements and activities during the final days of his visit to the United States. A prayer fulfilled It was the morning of 31 October 2018 and after meeting two American dignitaries earlier in the morning, Huzoor held a session of family Mulaqats that continued uninterrupted from 11.15am until 3.30pm. Amongst those to meet Huzoor for the first time was an Ahmadi now living in the United States, originally from Pakistan, Sheikh Latif Ahmad Akmal (49). Telling me about the experience, Sheikh Latif sahib said: “In 2008, I went to Qadian for the first time and as soon as I saw Minaratul Masih I prayed for two things. One was that in my life I would meet Hazrat Khalifatul Masih V (aba) at least once and, second, that my children remained forever firm in their faith. I do not care about meeting my children and being close to them in this world, I want to be close to them in the permanent state which is the next life.” 2 Sheikh Latif sahib continued: “Today, the first prayer of mine offered by me in Qadian came true and because I was able to take my children to see Huzoor and I know their faith will strengthen and so, in reality, both aspects of my prayer in 2008 have been fulfilled. -

Ansar Al-Nahl

Monthly Monthly Ansar 2006 Majlis Ansaullah,USA Vol. 11 Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. /2006 Vol. 17 No. 4 Vol. 17 No. 4 /2006 Al-Nahl Revelation of the Promised Messiah, ‘alaihissalam Messiah, ‘alaihissalam the Promised Revelation of Q4 of Publication A Quarterly 2006 in Review ·©¿öZ - Al-Nahl Page 1 About Al-Nahl The Al-Nahl (pronounced annahl) Nasir/year. All Ansar are requested to keep up on is published quarterly by Majlis Ansarullah, USA, time payment of their contributions for timely an auxiliary of the Ahmadiyya Movement in publication of the Al-Nahl. Islam, Inc., U.S.A., 15000 Good Hope Road, Subscription Information Silver Spring, MD 20905, U.S.A. The magazine is sent free of charge to all Articles/Essays for the Al-Nahl American Ansar whose addresses are complete Literary contributions, articles, essays, and available on the address database kept by the photographs, etc., for publication in the Al-Nahl Jama‘at, and they are identified as Ansar in the can be sent to the Editor at his address below. database. If you are one of the Ansar living in the It will be helpful if the contributions are saved States and yet are not receiving the magazine, onto a diskette in IBM compatible PC readable please contact your local officers to have your ASCII text format (text only with line breaks), address added, corrected, and/or have yourself MS Publisher, or in Microsoft Word for Windows identified as a member of Ansar. and the diskette or CD is sent, or contents are e- Other interested readers, institutions, or mailed or attached to an e-mail to the editor. -

Pakistan Bulletin

NOVEMBER 2005 PAKISTAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION BULLETIN 1/2005 Home Office Science and Research Group COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE Contents Paragraphs 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................1.01 2. SOUTH ASIA EARTHQUAKE.........................................................2.01 Overview.........................................................................................2.01 Relief aid.........................................................................................2.04 3. AHMADIS .......................................................................................3.01 October 2005 gun attack at mosque...............................................3.01 Positions of authority/voting figures................................................3.05 LIST OF SOURCES 1 Introduction 1.01 This Country of Origin Information Bulletin (COI Bulletin) has been produced by Research Development and Statistics (RDS), Home Office, from information about Pakistan obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. It does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.02 This COI Bulletin has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom 1.03 The COI Bulletin is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material,