A Tale of Two Ahmadiyya Mosques… 51 Even Take Place Thousands of Miles Away, but Their Effects Can Still Be Felt Locally

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motto of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community

The Community in Action Mosques: symbols of peace There are over 100 branches of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community throughout the The Ahmadiyya Muslim community has built over 15,000 mosques worldwide, UK and they actively work to spread the peaceful message of Islam. Islam including the first mosque in Spain for 700 years and one of the largest mosque in encourages religious harmony and interaction and it is the community’s belief that Sydney, Australia. In Calgary, Canada it has also built the largest mosque in the The Ahmadiyya tolerance and respect are the foundations of a peaceful society. The community is North American continent. committed to working with people of all faiths to enable everyone to practise their The first overseas mission of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community was established in religion without hindrance. It is London in 1913. It built the first mosque in London, the Fazl Mosque (pictured right) dedicated to serving society, in 1924. It is the only mosque known as ‘The London Mosque’. whether it is through raising funds Muslim Community for charitable causes or by giving The Baitul Futuh Mosque (cover and right), based in south London is one of the biggest our time to make our neighbourhoods cleaner. It believes all Muslims are duty in Western Europe. The total complex can accommodate more than 13,000 bound to serve the country in which they reside. worshippers. The mosque was voted as one of the top 50 modern buildings to visit in the world by The Information – a supplement magazine of The Independent national For more than 20 years, the community has held annual charity events raising money for local, national and international causes. -

Varieties of South Asian Islam Francis Robinson Research Paper No.8

Varieties of South Asian Islam Francis Robinson Research Paper No.8 Centre for Research September 1988 in Ethnic Relations University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7Al Francis Robinson is a Reader in History at the Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, University of London. For the past twenty years he has worked on Muslim politics and Islamic institutions in South Asia and is the author of many articles relating to these fields. His main books are: Separatism Among Indian Muslims: The Politics of the United Provinces' Muslims 1860-1923 (Cambridge, 1974); Atlas of the Islamic World since 1500 (Oxford, 1982); Islam in Modern South Asia (Cambridge, forthcoming); Islamic leadership in South Asia: The 'Ulama of Farangi Mahall from the seventeenth to the twentieth century (Cambridge, forthcoming). Varieties of South Asian Islam1 Over the past forty years Islamic movements and groups of South Asian origin have come to be established in Britain. They offer different ways, although not always markedly different ways, of being Muslim. Their relationships with each other are often extremely abrasive. Moreover, they can have significantly different attitudes to the state, in particular the non-Muslim state. An understanding of the origins and Islamic orientations of these movements and groups would seem to be of value in trying to make sense of their behaviour in British society. This paper will examine the following movements: the Deobandi, the Barelvi, the Ahl-i Hadith, the Tablighi Jamaat, the Jamaat-i Islami, the Ahmadiyya, and one which is unlikely to be distinguished in Britain by any particular name, but which represents a very important Islamic orientation, which we shall term the Modernist.2 It will also examine the following groups: Shias and Ismailis. -

Lajna Peace Symposium 2019

THE ROLE OF WOMEN AS NATION BUILDERS The Ahmadiyya Muslim Women’s Association (UK) is delighted to invite you to join us for our annual National Peace Symposium. Held at the largest Mosque in Western Europe, 2019 marks our “In te 10th Peace Symposium to date. This key event is attended by ladies from across the UK including parliamentarians, diplomats, faith and civic leaders as well as representatives from numerous charities establishment and faith communities. It promotes a deeper understanding of Islam and other faiths and seeks to and development inspire a concerted effort for lasting peace. of any nation or community Programme te women play Thursday 24th January 2019 a fundamental 5.00pm -Registration and Refreshments and vital role, as 5.30pm-Tours of the Mosque and Exhibitions te responsibility 6.30pm-Welcome and Keynote speeches for te taining 7.30pm-Q&A Session of te future 8.00pm-Dinner generations lies in te hands of Venue moters. They Baitul Futuh Mosque are te nation builders.” Baitul Futuh His Holiness Hazat Mirza 181 London Road Masroor Ahmad (may Morden, Surrey SM4 5PT Alah be his Helper) UK United Kingdom 24 Febuary 2018 The Baitul Futuh Mosque in South London is the prestigious venue of the annual Peace Symposium. Opened in 2003 the landmark building is the largest Mosque in Western Europe and architecturally, has been voted as one of the top 50 buildings in the world. About the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community true Islam Ahmadi Muslims believe that Islam is a universal religion of peace, with a simple but perfect message to develop and maintain a living relationship with a living God and to fulfl the rights of God’s creations, including all mankind, irrespective of their religious or faith choices. -

Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: a Study Of

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 5 Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud Abstract Pakistan’s successive constitutions, which enumerate guaranteed fundamental rights and pro- vide for the separation of state power and judicial review, contemplate judicial protection of vul- nerable sections of society against unlawful executive and legislative actions. This Article focuses upon the remarkably divergent pronouncements of Pakistan’s judiciary regarding the religious status and freedom of religion of one particular religious minority, the Ahmadis. The superior judiciary of Pakistan has visited the issue of religious freedom for the Ahmadis repeatedly since the establishment of the State, each time with a different result. The point of departure for this ex- amination is furnished by the recent pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (”Supreme Court” or “Court”) in Zaheeruddin v. State,’ wherein the Court decided that Ordinance XX of 1984 (”Ordinance XX” or ”Ordinance”), which amended Pakistan’s Penal Code to make the public prac- tice by the Ahmadis of their religion a crime, does not violate freedom of religion as mandated by the Pakistan Constitution. This Article argues that Zaheeruddin is at an impermissible variance with the implied covenant of freedom of religion between religious minorities and the Founding Fathers of Pakistan, the foundational constitutional jurisprudence of the country, and the dictates of international human rights law. -

Pakistan: Massacre of Minority Ahmadis | Human Rights Watch

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH http://www.hrw.org Pakistan: Massacre of Minority Ahmadis Attack on Hospital Treating Victims Shows How State Inaction Emboldens Extremists The mosque attacks and the June 1, 2010 subsequent attack on the hospital, amid rising sectarian violence, (New York) – Pakistan’s federal and provincial governments should take immediate legal action underscore the vulnerability of the against Islamist extremist groups responsible for threats and violence against the minority Ahmadiyya Ahmadi community. religious community, Human Rights Watch said today. Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher On May 28, 2010, extremist Islamist militants attacked two Ahmadiyya mosques in the central Pakistani city of Lahore with guns, grenades, and suicide bombs, killing 94 people and injuring well over a hundred. Twenty-seven people were killed at the Baitul Nur Mosque in the Model Town area of Lahore; 67 were killed at the Darul Zikr mosque in the suburb of Garhi Shahu. The Punjabi Taliban, a local affiliate of the Pakistani Taliban, called the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), claimed responsibility. On the night of May 31, unidentified gunmen attacked the Intensive Care Unit of Lahore’s Jinnah Hospital, where victims and one of the alleged attackers in Friday's attacks were under treatment, sparking a shootout in which at least a further 12 people, mostly police officers and hospital staff, were killed. The assailants succeeded in escaping. “The mosque attacks and the subsequent attack on the hospital, amid rising sectarian violence, underscore the vulnerability of the Ahmadi community,” said Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. -

Jalsa-UK-Booklet-2019.Pdf

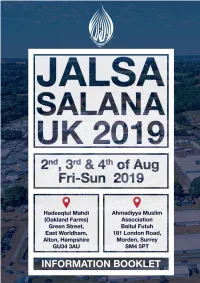

The Jalsa Salana The Annual Convention (Jalsa Salana) of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community UK is a unique event that brings over 35,000 participants from more than 90 countries to in- crease religious knowledge and promote a sense of peace in society. Eminent speakers discuss a range of religious topics and their relevance to contemporary society. Addi- tionally, a number of parliamentarians, civic leaders and diplomats from different countries also address the gather- ing and underline the conventions objective of enhancing unity, understanding and mutual respect. A special feature of this convention is that it is blessed by the presence of His Holiness Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the Head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. He address- es the convention over each of the three days, providing an invaluable insight into religious teachings and how they are a source of guidance for the world today. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (Peace be upon him) The Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (peace be upon him) of Qadian, India. He claimed under divine guidance to be the Promised Messiah and Imam Mahdi, whose advent was awaited by all the religions of the world. He championed the peaceful teachings of Islam, revived the Faith with a sense of purpose and inspired his followers to build a strong bond with God and to serve humanity with a selfless spirit of compassion and humility. The community is now established in more than 210 coun- tries and it spearheads an international effort to promote the true message of Islam and of service to humanity. -

Islam's Response to Extremism

In the Words of the Caliph His Holiness Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad Caliph (Spiritual Leader) of the Worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community Islam’s Response to EXTREMISM His Holiness, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad is widely acknowledged as a man of peace, who has continuously spoken out against extremism and called for a concerted effort to promote peace based on absolute justice. In this leaflet, we present just a few extracts of his statements. THE ACTIONS OF EXTREMISTS CONTRADICT THE TEACHINGS OF ISLAM “Islam’s teachings of peace prohibit all forms of extremism, to the extent, that even in a state of legitimate war, Allah has commanded that any action or punishment should remain proportionate to the crimes committed and that it is better if patience and forgiveness is manifest. Thus, all those so‐ called Muslims who are engaged in violence, injustice and brutality are inviting God’s wrath and anger to their doorstep.” (The 13th National Peace Symposium, Baitul Futuh Mosque, London, 19 March 2016) “...under no circumstances can murder ever be justified and those who seek to justify their hateful acts in the name of Islam are serving only to defame it in the worst possible way.” (Press Release in the aftermath of the Paris attacks, 14 November 2015) “In much of the world today there is a belief or perception that Islam is a religion of extremism and force... Let me say at the outset that this is entirely wrong and the reality is the complete opposite… The truth is that there are some selfish Muslims... who seek only to serve their own personal interests. -

Welcome Pack for New Ahmadis

Welcome pack for New Ahmadis Website: http://www.ahmadiconverts.org.uk Email: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. TEN CONDITIONS OF BAI’AT 3 3. NEW AHMADI CHECKLIST 5 4. THE AHMADIYYA MUSLIM COMMUNITY 6 5. BROTHERHOOD (MAWAKHAAT) 6 6. TRAINING (TARBIYYAT) COURSE 8 7. MEETINGS (MULAQAAT) WITH THE KHALIFA 10 8. EVENTS, MEETINGS AND FUNCTIONS 11 9. NEW AHMADI GATHERINGS (IJTEMAS) 12 10. FINANCIAL SACRIFICE 13 11. AHMADI MUSLIM ID (AIMS) CARDS 14 12. ASYLUM VERIFICATION 15 13. MARRIAGE 16 14. LETTERS TO THE KHALIFA 16 15. SUGGESTED READING 17 16. FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQS) 19 17. GLOSSARY 22 Front cover Image: New Ahmadis taking Bai’at (initiation) at the hand of His Holiness (aba), the Fifth Khalifa to the Promised Messiah, during a Group Mulaqaat (meeting) in Fazl mosque, London Website: http://www.ahmadiconverts.org.uk Email: [email protected] 2 1. INTRODUCTION – Congratulations (Mubarak)! You have obeyed God Almighty and accepted the Promised Messiah(as), who was prophesised to come by the Holy Prophet of Islam(saw), and in all of the great religions. The purpose of our initiation (Bai’at) is to win the pleasure of God Almighty. Everything is achieved through Allah’s Grace and Mercy. As new Ahmadis we must always safeguard and protect this sincere intention, while striving to worship Allah Almighty and serve His creation. We pray that this handbook will assist you on your path, offering both spiritual and practical guidance. Image: The Holy Kaaba, Al-Masjid al-Haram (Holy Mosque), Mecca 2. TEN CONDITIONS OF BAI’AT (INITIATION) - The Promised Messiah(as), Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, established the Ahmadiyya Muslim community purely on the foundations of the Holy Quran and the Practice (Sunnah) of the Holy Prophet of Islam (saw). -

Jul-Sep 2013

From the Editor... uly 25th 1913 was that memorable date in which Jama’at Ahmadiyya Meet the Team... Jwas first brought to the UK by Missionary Hazrat Chadhry Fateh Muhammad Sial Sahibra. 2013 marks the centenary of that joyous MARYAM EDITOR occasion. Munazza Khan EDITORIAL BOARD A historic address by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaba at the Houses of Hibba-Tul Mussawir Parliament is a key celebration that recently took place in the UK Hina Rehman to mark the successful 100 years of the establishment of Jama’at Maleeha Mansur Ahmadiyya in the UK. Among other celebrations that have been Meliha Hayat taking place across the country are charity walks and family picnics. Ramsha Hassan Salma Manahil Tahir A section of this magazine has been devoted to mark this special and joyous occasion. Readers can join in with the celebrations as we share MANAGER an exclusive article by respected Sadr Sahiba Lajna Imaillah UK, along Zanubia Ahmad with the Jama’at’s history in a timeline of major events. ASSISTANT MANAGER Alhamdolillah, the Jama’at has seen much progress in the propogation Dure Jamal Mala of Ahmadiyyat, the true Islam, since 1913. Last year, almost half a COVER DESIGN million poeple entered into the folds of Ahmadiyyat at the hands of our Atiyya Wasee beloved Huzur, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaba, at the 46th International Jalsa Salana UK. With the next Annual Convention coming up in PAGE DESIGN August, we all anticipate this number to rise with the help of Allah. Soumbal Qureshi Nabila Sosan Thus, God’s promise to all Muslims through the founder of Islam, The Holy Prophetsaw, of safeguarding the message of Islam through Khilafat ARABIC TYPING continues to be fulfilled, presently through unity at the hands of the Safina Nabeel Maham Khalifa-e-Waqt, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaba, who has repeatedly stated to world leaders that it is only at the hands of Khilafat that PRINTED BY Raqeem Press, Tilford UK humanity can be united. -

View a List of Publications

January 1, 2019 CHARLES H. KENNEDY Department of Political Science PO Box 7568, Reynolda Station Wake Forest University Winston-Salem, NC 27109 Office Telephone: (336) 758-5453 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION PhD Duke University (Political Science) 1979 MPP Duke University (Public Policy) 1978 AM Duke University (Political Science) 1975 BA Florida Presbyterian College, Politics and Asian Religion [Eckerd College], 1973 EMPLOYMENT 1994- Professor, Department of Political Science/Department of Politics and International Affairs, Wake Forest University 2006 Lecturer, University of Virginia, Semester at Sea 1989-94 Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Wake Forest University 1993 Director, WFU Program in Venice Italy 1991 Lecturer, University of Pittsburgh, Semester at Sea 1990 Visiting Professor, International Relations, Dhaka University (Bangladesh) 1985-89 Assistant Professor, Department of Politics, Wake Forest University 1981-84 Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Bowdoin College 1980-81 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of North Carolina at Greensboro1979-80 1978-80 Research Affiliate and Instructor, Islamic and Arabian Development Studies Center, Duke University COURSES TAUGHT AT WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY (1985-2017) PS 114 - Introduction to Comparative Politics PS 116 - Introduction to International Politics PS 219 - Policy Analysis PS 234 - Politics of Japan and the PRC PS 245/MLS 479 - Ethnonationalism PS 246 - Politics and Policy in South Asia PS 247/MLS 482 - Islam -

Khalifatul Masih IV Among the Quranic Prophecies Relating to Events Something Down to Its Smallest Constituents

Majlis Ansarullah UK I bear witness that there is none worthy of worship except Allah. He is One (and) has no partner, and I bear witness that Muhammad (peace be upon him) is His servant and messenger. I solemnly pledge that I shall endeavour throughout my life for the propagation and consolidation of Islam Ahmadiyyat, and for upholding the institution of Khilafat. I shall also be prepared to offer the greatest sacrifice for this cause. Moreover, I shall exhort my children to always remain dedicated and devoted to Khilafat. Insha’allah Contents 1. Darsul Qur’an Page 2 2. Darsul Hadith Page 3 3. Writings of the Promised Messiah (as) Page 4 4. EU Parliament Address Page 5 5. The Last Sermon of the Prophet Muhammad (saw) Page 12 6. Islam and Terrorism Page 11 7. Nuclear Holocaust Page 14 8. Is there a God ? Page 19 9. The Ansar Cycling Club Page 23 10. Ansar Activity Reports Page 29 Sadr Majlis Ansarullah UK Chief Editor Dr Ch. Ijaz Ur Rehman Dr Shamim Ahmad Qaid Isha’at Manager Raja Munir Ahmed Naeem Gulzar Posting & Despatch Saadat Jan (Incharge) Published by: Nasir Ahmad Mir Qiadat Isha’at Majlis Ansarullah UK Muhammad Yusuf Baitul Futuh, 181 London Road, Muhammad Azam Khan Morden, Surrey, Saleem Ahmed SM4 5PT Title Cover Tel: 020 8687 7810 Photos courtesy of Makhzan e Tasaweer Fax: 020 8687 7845 Design & Layout Email: [email protected] Aamir Ahmad Malik Web: ansar.org.uk DARSUL QUR’AN Al-Hajj Chapter 22: Verse 40 Permission to fight is given to those against whom war is made, because they have been wronged — and Allah indeed has power to help them. -

WORLD PEACE the 10 Th Annual Peace Symposium

THE CRITICAL STATE Of WORLD PEACE The 10 th Annual Peace Symposium 23 rd March 2013 Baitul Futuh Mosque, London An Overview of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community The Ahmadiyya Muslim community is a religious organisation, with branches in more than 200 countries. It is the most dynamic denomination of Islam in modern history, with an estimated membership in the tens of millions worldwide. It was established by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835-1908) in 1889 in a small and remote village called Qadian in Punjab, India. He claimed to be the expected reformer of the latter days and the awaited one of the world community of religions (the Mahdi and Messiah of the latter days). The community he started is an embodiment of the benevolent message of Islam in its pristine purity that promotes peace and universal brotherhood based on a belief in the Gracious and Ever-Merciful God. With this conviction, within a century, the Ahmadiyya Muslim community has expanded globally and it endeavours to practice the peaceful teachings of Islam by raising hundreds of thousands of pounds for charities, building schools and hospitals open to all and by encouraging learning through interfaith dialogue. The UK chapter of the community was established in 1913 and in 1924 it built London’s first purpose built mosque (in Southfields). It is therefore one of the oldest and most established Muslim organisations in Britain and now has more than 100 branches across Britain. The Khalifa of Islam: A Man of Peace Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad was elected as the fifth Khalifa of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in 2003.