Ecological Traps and Weed Biological Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis Samantha Lynn Davis Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Repository Citation Davis, Samantha Lynn, "Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis" (2015). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1433. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1433 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evaluating threats to the rare butterfly, Pieris virginiensis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Samantha L. Davis B.S., Daemen College, 2010 2015 Wright State University Wright State University GRADUATE SCHOOL May 17, 2015 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY Samantha L. Davis ENTITLED Evaluating threats to the rare butterfly, Pieris virginiensis BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy. Don Cipollini, Ph.D. Dissertation Director Don Cipollini, Ph.D. Director, Environmental Sciences Ph.D. Program Robert E.W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Committee on Final Examination John Stireman, Ph.D. Jeff Peters, Ph.D. Thaddeus Tarpey, Ph.D. Francie Chew, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Davis, Samantha. Ph.D., Environmental Sciences Ph.D. -

1668667-Tm-Rev0-Stouffville Natural Environment-16May2018.Docx

TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM DATE May 16, 2018 PROJECT No. 1668667 TO Kevin Brown, Senior Municipal Engineer - Project Manager The Municipal Infrastructure Group Ltd. CC Heather Melcher, M.Sc. FROM Gwendolyn Weeks, H.B.Sc.Env. EMAIL [email protected] NATURAL ENVIRONMENT EXISTING CONDITIONS BRIEF, SCHEDULE B MUNICIPAL CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT, WATER SYSTEM UPGRADES, WHITCHURCH-STOUFFVILLE, ONTARIO Background & Summary The Municipal Infrastructure Group (TMIG) retained Golder Associates Ltd. (Golder) to prepare a Natural Environment Existing Conditions technical memorandum as part of a Schedule B Class Environmental Assessment (EA) for water system upgrades in the Town of Whitchurch-Stouffville, Regional Municipality of York, Ontario (the Study Area) (Figure 1; Attachment A). The purpose of this memo is to identify the known significant natural features in the Study Area that may pose a constraint to the project. The natural features considered in this memo are those listed in the Provincial Policy Statement (MMA, 2014), including: Significant wetlands (PSW) and coastal wetlands; Significant woodlands; Significant valleylands; Significant wildlife habitat; Significant areas of natural and scientific interest (ANSI); Fish habitat; and Habitat of endangered and threatened species and threatened species. Also considered are the natural heritage features as listed in the Greenbelt Plan (Ontario, 2017a) and the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan (ORMCP) (MMA, 2017b). Golder Associates Ltd. 1931 Robertson Road, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K2H 5B7 Tel: +1 (613) 592 9600 Fax: +1 (613) 592 9601 www.golder.com Golder Associates: Operations in Africa, Asia, Australasia, Europe, North America and South America Golder, Golder Associates and the GA globe design are trademarks of Golder Associates Corporation. -

Yukon Butterflies a Guide to Yukon Butterflies

Wildlife Viewing Yukon butterflies A guide to Yukon butterflies Where to find them Currently, about 91 species of butterflies, representing five families, are known from Yukon, but scientists expect to discover more. Finding butterflies in Yukon is easy. Just look in any natural, open area on a warm, sunny day. Two excellent butterfly viewing spots are Keno Hill and the Blackstone Uplands. Pick up Yukon’s Wildlife Viewing Guide to find these and other wildlife viewing hotspots. Visitors follow an old mining road Viewing tips to explore the alpine on top of Keno Hill. This booklet will help you view and identify some of the more common butterflies, and a few distinctive but less common species. Additional species are mentioned but not illustrated. In some cases, © Government of Yukon 2019 you will need a detailed book, such as , ISBN 978-1-55362-862-2 The Butterflies of Canada to identify the exact species that you have seen. All photos by Crispin Guppy except as follows: In the Alpine (p.ii) Some Yukon butterflies, by Ryan Agar; Cerisy’s Sphynx moth (p.2) by Sara Nielsen; Anicia such as the large swallowtails, Checkerspot (p.2) by Bruce Bennett; swallowtails (p.3) by Bruce are bright to advertise their Bennett; Freija Fritillary (p.12) by Sonja Stange; Gallium Sphinx presence to mates. Others are caterpillar (p.19) by William Kleeden (www.yukonexplorer.com); coloured in dull earth tones Butterfly hike at Keno (p.21) by Peter Long; Alpine Interpretive that allow them to hide from bird Centre (p.22) by Bruce Bennett. -

Cedarburg Bog Dragonflies & Butterflies List

Spiny Baskettail White-faced Meadowhawk Slender Spreadwing BUTTERFLIES, DRAGONFLIES and Epitheca spinigera Sympetrum obtrusum Lestes rectangularis DAMSELFLIES OF Forcipate Emerald Lyre-tipped Spreadwing Ruby Meadowhawk THE CEDARBURG BOG Somatochlora forcipata Lestes unguiculatus Sympetrum rubicundulum **Hine's Emerald - endangered The Cedarburg Bog system is made up of about 2200 Somatochlora hineana Band-winged Meadowhawk Pond Damsels - Coenagrionidae acres that include a variety of plant communities Sympetrum semicinctum Kennedy's Emerald Blue-fronted Dancer including conifer and hardwood swamps, sedge Somatochlora kennedyi Autumn/Yellow-legged Meadowhawk Argia apicalis meadow, marsh, several lakes, fen, and upland forests. Brush-tipped Emerald Sympetrum vicinum Variable/Violet Dancer There is public access at the north end of the Bog (Hwy 33) and south end (Cedar Sauk Rd). The UWM Field Somatochlora walshii Argia fumipennis violacea Station trails are only open to the public for group use Blue Dasher Williamson's Emerald arranged in advance or at public events. Pachydiplax longipennis Somatochlora williamsoni Boreal Bluet Enallagma boreale Please do not harass, harm or collect the butterflies Skimmers - Libellulidae Carolina Saddlebags and dragonflies you see here. Tramea caroline Familiar Bluet Common Whitetail Enallagma civile Plathemis lydia Black Saddlebags Like all species lists, these lists are works-in-progress. Tramea lacerata If you see a butterfly or dragonfly that is not on the Slaty Skimmer - special concern Marsh Bluet list, please report it to Friends of the Cedarburg Bog, Libellula incesta Red Saddlebags Enallagma ebrium c/o UWM Field Station, 3095 Blue Goose Rd, Saukville, Tramea onusta Widow Skimmer WI 53080. Or use the Friends of the Cedarburg Bog Skimming Bluet Libellula luctosa website at http://bogfriends.org/contact-us. -

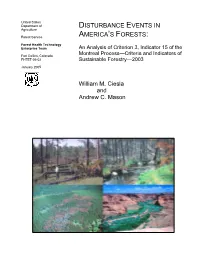

Processes and Agents Affecting the Forests of the United States – an Overview

United States Department of DISTURBANCE EVENTS IN Agriculture Forest Service AMERICA’S FORESTS: Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team An Analysis of Criterion 3, Indicator 15 of the Fort Collins, Colorado Montreal Process—Criteria and Indicators of FHTET-05-02 Sustainable Forestry—2003 January 2005 William M. Ciesla and Andrew C. Mason Examples of disturbance events in America’s forests: Upper left: Windthrow caused by a hurricane in southern Mississippi. Upper right: Stand replacement fire in lodgepole pine forest near Pinegree Park, Colorado. Lower left: Bark beetle outbreak along the Colorado Front Range. Lower right: Invasion of Russian olive (trees at center with blueish foliage) in Canyon de Chelley National Monument, Arizona. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call 202-720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for information only and does not constitute an endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Disturbance Events in America’s Forests: An Analysis of Criterion 3, Indicator 15, Montreal Process—Criteria and Indicators of Sustainable Forestry—2003 William M. -

Biogeography and Phenology of Oviposition Preference and Larval Performance of Pieris Virginiensis Butterflies on Native and Invasive Host Plants

Biol Invasions DOI 10.1007/s10530-017-1543-9 ORIGINAL PAPER Biogeography and phenology of oviposition preference and larval performance of Pieris virginiensis butterflies on native and invasive host plants Kate E. Augustine . Joel G. Kingsolver Received: 10 February 2017 / Accepted: 14 August 2017 Ó Springer International Publishing AG 2017 Abstract In invaded environments, formerly reli- driven by the early senescence of C. diphylla and able cues might no longer be associated with adaptive suggests a seasonal component to the impact of A. outcomes and organisms can become trapped by their petiolata. Therefore, the already short flight season of evolved responses. The invasion of Alliaria petiolata P. virginiensis could become further constrained in (garlic mustard) into the native habitat of Pieris invaded populations. virginiensis (West Virginia White) is one such exam- ple. Female butterflies oviposit on the invasive plant Keywords West Virginia White Á Alliaria petiolata Á because it is related to their preferred native host plant Evolutionary trap Á Novel plant–insect interactions Cardamine diphylla (toothwort), but larvae are unable to complete development. We have studied the impact of the A. petiolata invasion on P. virginiensis butter- flies in the Southeastern USA by comparing oviposi- Introduction tion preference and larval survival on both plants in North Carolina (NC) populations without A. petiolata Invading species can lead to novel ecological com- and West Virginia (WV) populations where A. peti- munities in which existing biotic interactions are olata is present. Larval survival to the 3rd instar was altered and new interactions are created (van der equally low in both populations when raised on A. -

Species List

Species List Invertebrates of Oak Hammock Marsh PHYLUM MOLLUSCA Class Gastropoda Lymnaeidae Pond snail Family Class Bivalvia Pisidiidae Fingernail clam Family Unionidae Pearly mussel Family PHYLUM ANNELIDA Class Hirudinea Leeches PHYLUM ARTHROPODA Class Arachnida Order Acari Freshwater mites Order Aranaeae Dock spiders Class Crustacea Subclass Branchiopoda Order Cladocera Water fleas Subclass Ostracoda Seed shrimp Subclass Copepoda Copepods Subclass Malacostraca Order Amphipoda Sideswimmers Order Decapoda Crayfish Class Insecta Order Ephemeroptera Mayflies Order Odonata Dragonflies and Damselflies Lestidae Spreadwing Family Lestes congener Spotted spreadwing Leste tardif Lestes disjunctus Northern Spreadwing Leste disjoint Lestes dryas Emerald spreadwing Leste dryade Lestes forcipatus Sweetflag spreadwing Leste à forceps Lestes inaequalis Elegant spreadwing Leste inégal Lestes rectangularis Slender spreadwing Leste élancé Lestes unguiculatus Lyre-tipped spreadwing Leste onguiculé Species List continued Coenagrionidae Pond damsel Family Coenagrion resolutum Taiga Bluet Agrion résolu Enallagma annexum Northern bluet Agrion porte-coupes Enallagma civile Familiar bluet Agrion civil Enallagma clausum Alkali bluet Agrion halophile Enallagma ebrium Marsh bluet Agrion enivré Enallagma hageni Hagen’s bluet Agrion de Hagen Ischnura perparva Western forktail Ischnura verticalis Eastern Forktail Agrion vertical Nehalennia irene Sedge sprite Déesse paisible Aeshnidae Darner Family Aeshna canadensis Canada darner Aeschne du Canada Aeshna constricta -

A SKELETON CHECKLIST of the BUTTERFLIES of the UNITED STATES and CANADA Preparatory to Publication of the Catalogue Jonathan P

A SKELETON CHECKLIST OF THE BUTTERFLIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA Preparatory to publication of the Catalogue © Jonathan P. Pelham August 2006 Superfamily HESPERIOIDEA Latreille, 1809 Family Hesperiidae Latreille, 1809 Subfamily Eudaminae Mabille, 1877 PHOCIDES Hübner, [1819] = Erycides Hübner, [1819] = Dysenius Scudder, 1872 *1. Phocides pigmalion (Cramer, 1779) = tenuistriga Mabille & Boullet, 1912 a. Phocides pigmalion okeechobee (Worthington, 1881) 2. Phocides belus (Godman and Salvin, 1890) *3. Phocides polybius (Fabricius, 1793) =‡palemon (Cramer, 1777) Homonym = cruentus Hübner, [1819] = palaemonides Röber, 1925 = ab. ‡"gunderi" R. C. Williams & Bell, 1931 a. Phocides polybius lilea (Reakirt, [1867]) = albicilla (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) = socius (Butler & Druce, 1872) =‡cruentus (Scudder, 1872) Homonym = sanguinea (Scudder, 1872) = imbreus (Plötz, 1879) = spurius (Mabille, 1880) = decolor (Mabille, 1880) = albiciliata Röber, 1925 PROTEIDES Hübner, [1819] = Dicranaspis Mabille, [1879] 4. Proteides mercurius (Fabricius, 1787) a. Proteides mercurius mercurius (Fabricius, 1787) =‡idas (Cramer, 1779) Homonym b. Proteides mercurius sanantonio (Lucas, 1857) EPARGYREUS Hübner, [1819] = Eridamus Burmeister, 1875 5. Epargyreus zestos (Geyer, 1832) a. Epargyreus zestos zestos (Geyer, 1832) = oberon (Worthington, 1881) = arsaces Mabille, 1903 6. Epargyreus clarus (Cramer, 1775) a. Epargyreus clarus clarus (Cramer, 1775) =‡tityrus (Fabricius, 1775) Homonym = argentosus Hayward, 1933 = argenteola (Matsumura, 1940) = ab. ‡"obliteratus" -

Butterfly!Survey!

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Vermont!Butterfly!Survey! ! 2002!–!2007! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Final!Report!to!the!Natural!Heritage!Information! ! Project!of!the!Vermont!Department!of!Fish!and! Wildlife! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! September!30,!2010! ! Kent!McFarland,!Project!Director! ! Sara!Zahendra,!Staff!Biologist! Vermont!Center!for!Ecostudies! ! Norwich,!Vermont!05055! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! Acknowledgements!............................................................................................................................!4! Introduction!and!Methodology!..........................................................................................................!6! Project!Planning!and!Management!...............................................................................................................!6! Recording!Methods!and!Data!Collection!.......................................................................................................!7! Data!Processing!............................................................................................................................................!9! PreKProject!Records!....................................................................................................................................!11! Summary!of!Results!.........................................................................................................................!11! Conservation!of!Vermont!Butterflies!................................................................................................!19! -

Butler County Natural Heritage Inventory Update 2021

Butler County Natural Heritage Inventory Update 2021 Butler County Natural Heritage Inventory 2021 Update Anna Johnson and Christopher Tracey, editors Prepared for: Southwest Pennsylvania Commission 112 Washington Pl #500 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Prepared by: Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program 800 Waterfront Drive Pittsburgh, PA 15222 Please cite this Natural Heritage Inventory report as: Johnson, Anna and Christopher Tracey, editors. 2021. Butler County Natural Heritage Inventory. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Pittsburgh, PA. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to acknowledge the citizens and landowners of Butler County and surrounding areas who volunteered infor- mation, time, and effort to the inventory and granted permission to access land. A big thank you goes to those who suggested areas of interest, provided data, and assisted with field surveys. Additional thanks goes to Ryan Gordon of the Southwest Pennsylvania Commission for providing support for this project. Advisory Committee to the 2021 update to the Butler County Natural Heritage Inventory: • Mark Gordon — Butler County Director of Planning and Economic Development • Joel MacKay — Butler County Planner • Sheryl Kelly — Butler County Environment Specialist We want to recognize the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program and NatureServe for providing the foundation for the work that we perform for these studies. Current and former PNHP staff that contributed to this report includes JoAnn Albert, Jaci Braund, Charlie Eichelberger, Kierstin Carlson, Mary Ann Furedi, Steve Grund, Amy Jewitt, Anna Johnson, Susan Klugman, John Kunsman, Betsy Leppo, Jessica McPherson, Molly Moore, Ryan Miller, Greg Podniesinski, Megan Pulver, Erika Schoen, Scott Schuette, Emily Szoszorek, Kent Taylor, Christopher Tracey, Natalie Virbitsky, Jeff Wagner, Denise Watts, Joe Wisgo, Pete Woods, David Yeany, and Ephraim Zimmerman. -

Book Review, of Systematics of Western North American Butterflies

(NEW Dec. 3, PAPILIO SERIES) ~19 2008 CORRECTIONS/REVIEWS OF 58 NORTH AMERICAN BUTTERFLY BOOKS Dr. James A. Scott, 60 Estes Street, Lakewood, Colorado 80226-1254 Abstract. Corrections are given for 58 North American butterfly books. Most of these books are recent. Misidentified figures mostly of adults, erroneous hostplants, and other mistakes are corrected in each book. Suggestions are made to improve future butterfly books. Identifications of figured specimens in Holland's 1931 & 1898 Butterfly Book & 1915 Butterfly Guide are corrected, and their type status clarified, and corrections are made to F. M. Brown's series of papers on Edwards; types (many figured by Holland), because some of Holland's 75 lectotype designations override lectotype specimens that were designated later, and several dozen Holland lectotype designations are added to the J. Pelham Catalogue. Type locality designations are corrected/defined here (some made by Brown, most by others), for numerous names: aenus, artonis, balder, bremnerii, brettoides, brucei (Oeneis), caespitatis, cahmus, callina, carus, colon, colorado, coolinensis, comus, conquista, dacotah, damei, dumeti, edwardsii (Oarisma), elada, epixanthe, eunus, fulvia, furcae, garita, hermodur, kootenai, lagus, mejicanus, mormo, mormonia, nilus, nympha, oreas, oslari, philetas, phylace, pratincola, rhena, saga, scudderi, simius, taxiles, uhleri. Five first reviser actions are made (albihalos=austinorum, davenporti=pratti, latalinea=subaridum, maritima=texana [Cercyonis], ricei=calneva). The name c-argenteum is designated nomen oblitum, faunus a nomen protectum. Three taxa are demonstrated to be invalid nomina nuda (blackmorei, sulfuris, svilhae), and another nomen nudum ( damei) is added to catalogues as a "schizophrenic taxon" in order to preserve stability. Problems caused by old scientific names and the time wasted on them are discussed. -

Butterflies and Moths of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail