Sentinels on the Wing: the Status and Conservation of Butterflies in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panicledleaf Ticktrefoil (Desmodium Paniculatum) Plant Fact Sheet

Plant Fact Sheet Hairstreak (Strymon melinus) eat the flowers and PANICLEDLEAF developing seedpods. Other insect feeders include many kinds of beetles, and some species of thrips, aphids, moth TICKTREFOIL caterpillars, and stinkbugs. The seeds are eaten by some upland gamebirds (Bobwhite Quail, Wild Turkey) and Desmodium paniculatum (L.) DC. small rodents (White-Footed Mouse, Deer Mouse), while Plant Symbol = DEPA6 the foliage is readily eaten by White-Tailed Deer and other hoofed mammalian herbivores. The Cottontail Contributed by: USDA, NRCS, Norman A. Berg National Rabbit also consumes the foliage. Plant Materials Center, Beltsville, MD Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g. threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description and Adaptation Panicledleaf Ticktrefoil is a native, perennial, wildflower that grows up to 3 feet tall. The genus Desmodium: originates from Greek meaning "long branch or chain," probably from the shape and attachment of the seedpods. The central stem is green with clover-like, oblong, multiple green leaflets proceeding singly up the stem. The showy purple flowers appear in late summer and grow arranged on a stem maturing from the bottom upwards. In early fall, the flowers produce leguminous seed pods approximately ⅛ inch long. Panicledleaf Photo by Rick Mark [email protected] image used with permission Ticktrefoil plants have a single crown. This wildflower is a pioneer species that prefers some disturbance from Alternate Names wildfires, selective logging, and others causes. The sticky Panicled Tick Trefoil seedpods cling to the fur of animals and the clothing of Uses humans and are carried to new locations. -

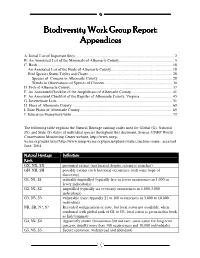

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

Uncus Shaped Akin to Elephant Tusks Defines a New Genus for Two Very Different-In-Appearance Neotropical Skippers (Hesperiidae: Pyrginae)

The Journal Volume 45: 101-112 of Research on the Lepidoptera ISSN 0022-4324 (PR in T ) THE LEPIDOPTERA RESEARCH FOUNDATION, 29 DE C EMBER 2012 ISSN 2156-5457 (O N L in E ) Uncus shaped akin to elephant tusks defines a new genus for two very different-in-appearance Neotropical skippers (Hesperiidae: Pyrginae) Nic K V. GR ishin Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Departments of Biophysics and Biochemistry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX, USA 75390-9050 [email protected] Abstract. Analyses of male genitalia, other aspects of adult, larval and pupal morphology, and DNA COI barcode sequences suggest that Potamanaxas unifasciata (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1867) does not belong to Potamanaxas Lindsey, 1925 and not even to the Erynnini tribe, but instead is more closely related to Milanion Godman & Salvin, 1895 and Atarnes Godman & Salvin, 1897, (Achlyodini). Unexpected and striking similarities are revealed in the male genitalia of P. unifasciata and Atarnes hierax (Hopffer, 1874). Their genitalia are so similar and distinct from the others that one might casually mistake them for the same species. Capturing this uniqueness, a new genus Eburuncus is erected to include: E. unifasciata, new combination (type species) and E. hierax, new combination. Key words: phylogenetic classification, monophyletic taxa, immature stages, DNA barcodes,Atarnes sallei, Central America, Peru. INTRODUCT I ON 1982-1999). Most of Burns’ work derives from careful analysis of genitalia, recently assisted by morphology Comprehensive work by Evans (e.g. Evans, 1937; of immature stages and molecular evidence (e.g. 1952; 1953) still remains the primary source of Burns & Janzen, 2005; Burns et al., 2009; 2010). -

Pollinator–Friendly Parks

POLLINATOR–FRIENDLY PARKS How to Enhance Parks, Gardens, and Other Greenspaces for Native Pollinator Insects Matthew Shepherd, Mace Vaughan, and Scott Hoffman Black The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, Portland, OR The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation is an international, nonprofit, member–supported organiza- tion dedicated to preserving wildlife and its habitat through the conservation of invertebrates. The Society promotes protection of invertebrates and their habitat through science–based advocacy, conservation, and education projects. Its work focuses on three principal areas—endangered species, watershed health, and pollinator conservation. Copyright © 2008 (2nd Edition) The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. 4828 SE Hawthorne Boulevard, Portland, OR 97215 Tel (503) 232-6639 Fax (503) 233-6794 www.xerces.org Acknowledgements Thank you to Bruce Barbarasch (Tualatin Hills Park & Recreation District, OR) and Lisa Hamerlynck (City of Lake Oswego, OR) for reviewing early drafts. Their guidance and suggestions greatly improved these guide- lines. Thank you to Eric Mader and Jessa Guisse for help with the plant lists, and to Caitlyn Howell and Logan Lauvray for editing assistance. Funding for our pollinator conservation program has been provided by the Bradshaw-Knight Foundation, the Bullitt Foundation, the Columbia Foundation, the CS Fund, the Disney Wildlife Conservation Fund, the Dudley Foundation, the Gaia Fund, NRCS Agricultural Wildlife Conservation Center, NRCS California, NRCS West National Technical Support Center, the Panta Rhea Foundation, the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Founda- tion, the Turner Foundation, the Wildwood Foundation, and Xerces Society members Photographs We are grateful to Jeff Adams, Scott Bauer/USDA–ARS, John Davis/GORGEous Nature, Chris Evans/ www.forestryimages.com, Bruce Newhouse, Jeff Owens/Metalmark Images, and Edward S. -

Biological Technical Report for the Nichols Mine Project

Biological Technical Report for the Nichols Mine Project June 8, 2016 Prepared for: Nichols Road Partners, LLC P.O. Box 77850 Corona, CA 92877 Prepared by: Alden Environmental, Inc. 3245 University Avenue, #1188 San Diego, CA 92104 Nichols Road Mine Project Biological Technical Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Title Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1 1.1 Project Location ..................................................................................................1 1.2 Project Description ..............................................................................................1 2.0 METHODS & SURVEY LIMITATIONS .................................................................1 2.1 Literature Review ................................................................................................1 2.2 Biological Surveys ..............................................................................................2 2.2.1 Vegetation Mapping..................................................................................3 2.2.2 Jurisdictional Delineations of Waters of U.S. and Waters of the State ....4 2.2.3 Sensitive Species Surveys .........................................................................4 2.2.4 Survey Limitations ....................................................................................5 2.2.5 Nomenclature ............................................................................................5 3.0 REGULATORY -

Butterflies of the Wesleyan Campus

BUTTERFLIES OF THE WESLEYAN CAMPUS SWALLOWTAILS Hairstreaks (Subfamily - Theclinae) (Family PAPILIONIDAE) Great Purple Hairstreak - Atlides halesus Coral Hairstreak - Satyrium titus True Swallowtails Banded Hairstreak - Satyrium calanus (Subfamily - Papilioninae) Striped Hairstreak - Satyrium liparops Pipevine Swallowtail - Battus philenor Henry’s Elfin - Callophrys henrici Zebra Swallowtail - Eurytides marcellus Eastern Pine Elfin - Callophrys niphon Black Swallowtail - Papilio polyxenes Juniper Hairstreak - Callophrys gryneus Giant Swallowtail - Papilio cresphontes White M Hairstreak - Parrhasius m-album Eastern Tiger Swallowtail - Papilio glaucus Gray Hairstreak - Strymon melinus Spicebush Swallowtail - Papilio troilus Red-banded Hairstreak - Calycopis cecrops Palamedes Swallowtail - Papilio palamedes Blues (Subfamily - Polommatinae) Ceraunus Blue - Hemiargus ceraunus Eastern-Tailed Blue - Everes comyntas WHITES AND SULPHURS Spring Azure - Celastrina ladon (Family PIERIDAE) Whites (Subfamily - Pierinae) BRUSHFOOTS Cabbage White - Pieris rapae (Family NYMPHALIDAE) Falcate Orangetip - Anthocharis midea Snouts (Subfamily - Libytheinae) American Snout - Libytheana carinenta Sulphurs and Yellows (Subfamily - Coliadinae) Clouded Sulphur - Colias philodice Heliconians and Fritillaries Orange Sulphur - Colias eurytheme (Subfamily - Heliconiinae) Southern Dogface - Colias cesonia Gulf Fritillary - Agraulis vanillae Cloudless Sulphur - Phoebis sennae Zebra Heliconian - Heliconius charithonia Barred Yellow - Eurema daira Variegated Fritillary -

Phylogenetic Relationships and Historical Biogeography of Tribes and Genera in the Subfamily Nymphalinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKBIJBiological Journal of the Linnean Society 0024-4066The Linnean Society of London, 2005? 2005 862 227251 Original Article PHYLOGENY OF NYMPHALINAE N. WAHLBERG ET AL Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2005, 86, 227–251. With 5 figures . Phylogenetic relationships and historical biogeography of tribes and genera in the subfamily Nymphalinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) NIKLAS WAHLBERG1*, ANDREW V. Z. BROWER2 and SÖREN NYLIN1 1Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Zoology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331–2907, USA Received 10 January 2004; accepted for publication 12 November 2004 We infer for the first time the phylogenetic relationships of genera and tribes in the ecologically and evolutionarily well-studied subfamily Nymphalinae using DNA sequence data from three genes: 1450 bp of cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) (in the mitochondrial genome), 1077 bp of elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1-a) and 400–403 bp of wing- less (both in the nuclear genome). We explore the influence of each gene region on the support given to each node of the most parsimonious tree derived from a combined analysis of all three genes using Partitioned Bremer Support. We also explore the influence of assuming equal weights for all characters in the combined analysis by investigating the stability of clades to different transition/transversion weighting schemes. We find many strongly supported and stable clades in the Nymphalinae. We are also able to identify ‘rogue’ -

Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis Persius Persius

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada ENDANGERED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge M.L. Holder for writing the status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Environment Canada. The COSEWIC report review was overseen and edited by Theresa B. Fowler, Co-chair, COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’Hespérie Persius de l’Est (Erynnis persius persius) au Canada. Cover illustration: Eastern Persius Duskywing — Original drawing by Andrea Kingsley ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 Catalogue No. CW69-14/475-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43258-4 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name Eastern Persius Duskywing Scientific name Erynnis persius persius Status Endangered Reason for designation This lupine-feeding butterfly has been confirmed from only two sites in Canada. -

Butterfly and Punt Partners of the Butterfly Garden (K-6)

BUTTERFLY AND PUNT PARTNERS OF THE BUTTERFLY GARDEN (K-6) Acmon Blue (Icaricia acmon) Non-migratory: Adults seen spring through fall Larval Diet: Buckwheat, lupine, clover and many kinds of legumes. Size: 3/4"-I" Description: Bluish-purple in color; orange edge at the base of hind wing; large orange spots under the hind wing. Adults seen in many communities. Did You Know? Eggs are laid on the host plant from January onward, and the butterflies pupate in leaf litter beneath the plants. larval stage feeds on: California Buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum) Origin: Native Plant Size: 1' - 2' tall shrub with long stalks Leaf Description: Small course leaves attached to long branching stems. The underside of the leaves are covered in a soft, white fuzz. Flower Description: Large compound head with white flowers. Blooms from March to October. Did you know? Buckwheat is one of the few acceptable food plants for the acmon blue butterfly. Echo Blue (Celastrina ladon echo) Non-migratory: However, its range extends from Alaska to Central America Larval Diet: Many different plants, including wild lilac/ceanothus, buckeye, chamise, lotus and huckleberry. Caterpillar's eat buds, flowers, leaves and young fruit. Size: 7/8"-1 1/4" Description: Light purple; front wing tips bordered in black; hind wings bordered in white. Can live in all local communities Did You Know? Larvae are often cared for by ants. larval stage feeds on: Ceanothus or Wild Lilac (Ceanothus spp.) Origin: Native Plant Size: Chaparral shrub can be 6' tall or more. Leaf Description: Small tough evergreen leaves on very stiff branches; brilliant glossy green above, dull below. -

Usands in Walton Co., Coming in from the Gulf, Flying in a Northerly Direction, but Only Near the Water

NEW S Number 3 15 April 1969 of the Lepidopterists' Society Editorial Committee of the NEWS E. J. Newcomer, Editor 1509 Summitview, Yakima, Washington 98902, U. S. A. J. Donald Eff John Heath F. W. Preston H. A. Freeman G. Hesselbarth G. W. Rawson L. Paul Grey L. M. Martin Fred Thorne Richard He itzman Bryant Mather E. C. Welling M. L. D. Miller ANNUAL SUMMARY IN THIS ISSUE ... This Summary is one of the best. All coordinators got their reports to me in good time (March 27, and most of them earlier) and they were well written, which I appreciate very much as I cannot be familiar with conditions allover the area. I was a bit disappointed at the small nu.mber of reports received from my own Zone, only 6. Except of course, for Zones VIII and IX, from 15 to 31 reports came to the Coordinators, with a maximum of 31 for Zone I. The total was 135. -"'--Editor. SUMMARY OF MIGRATION There is more information than usual in this Summary about the migration of Vanessa cardui and Danaus plexippus, hence a summary of this migration is given here: V. cardui., --Migrating towards the NW in mid-March in Sonora, Mexico, but curiously no reports of this species from Arizona, New Mexico or Nevada. Migrating north in Cal if ornia, starting in San Diego Co., March 2 and reaching San Francisco Bay area March 27. Appearing in Colo. (Denver and vicinity) in early June. None reported north of these states. In the East, appeared in Missouri March 30 to early May; Iowa, April 10, maximum May 2-5 (see Iowa report for deatils); reached S. -

Plant Inventory at Missouri National Recreational River

Inventory of Butterflies at Fort Union Trading Post and Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Sites in 2004 --<o>-- Final Report Submitted by: Ronald Alan Royer, Ph.D. Burlington, North Dakota 58722 Submitted to: Northern Great Plains Inventory & Monitoring Coordinator National Park Service Mount Rushmore National Memorial Keystone, South Dakota 57751 October 1, 2004 Executive Summary This document reports inventory of butterflies at Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (NHS) and Fort Union Trading Post NHS, both administered by the National Park Service in the state of North Dakota. Field work consisted of strategically timed visits throughout Summer 2004. The inventory employed “checklist” counting based on the author's experience with habitat for the various species expected from each site. This report is written in two separate parts, one for each site. Each part contains an annotated species list for that site. For possible later GIS use, noteworthy species encounters are reported by UTM coordinates, all of which are provided conveniently in a table within the report narrative for each site. An annotated listing is also included for each species at each site. Each of these provides a brief description of typical habitat, principal larval host(s), and information on adult phenology. This information is followed by abbreviated citations for published works in which more detailed information may be located. Recommendations are then made for each site on the basis of endemism, prairie butterfly conservation and -

Guidance Document on the Strict Protection of Animal Species of Community Interest Under the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC

Guidance document on the strict protection of animal species of Community interest under the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC Final version, February 2007 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 I. CONTEXT 6 I.1 Species conservation within a wider legal and political context 6 I.1.1 Political context 6 I.1.2 Legal context 7 I.2 Species conservation within the overall scheme of Directive 92/43/EEC 8 I.2.1 Primary aim of the Directive: the role of Article 2 8 I.2.2 Favourable conservation status 9 I.2.3 Species conservation instruments 11 I.2.3.a) The Annexes 13 I.2.3.b) The protection of animal species listed under both Annexes II and IV in Natura 2000 sites 15 I.2.4 Basic principles of species conservation 17 I.2.4.a) Good knowledge and surveillance of conservation status 17 I.2.4.b) Appropriate and effective character of measures taken 19 II. ARTICLE 12 23 II.1 General legal considerations 23 II.2 Requisite measures for a system of strict protection 26 II.2.1 Measures to establish and effectively implement a system of strict protection 26 II.2.2 Measures to ensure favourable conservation status 27 II.2.3 Measures regarding the situations described in Article 12 28 II.2.4 Provisions of Article 12(1)(a)-(d) in relation to ongoing activities 30 II.3 The specific protection provisions under Article 12 35 II.3.1 Deliberate capture or killing of specimens of Annex IV(a) species 35 II.3.2 Deliberate disturbance of Annex IV(a) species, particularly during periods of breeding, rearing, hibernation and migration 37 II.3.2.a) Disturbance 37 II.3.2.b) Periods