Best Practice-Resuscitation Triage 540.21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of Acute Liver Failure In

Management of Acute Liver Failure in ICU Philip Berry MRCP, Clinical Research Fellow, Institute of Liver Studies, Kings College Hospital, London, UK Email: [email protected] Self assessment questions Scenario: A twenty-year-old female is brought into the Emergency Department having been found unconscious in her bedsit. There is no other recent history. She did not respond to a bolus of 50% dextrose in the ambulance, despite having an unrecordable blood glucose when tested by the paramedics. While she is being intubated on account of reduced level of consciousness, an arterial blood gas sample reveals profound lactic acidosis (pH 7.05, pCO2 2.5 kPa, base deficit – 10, lactate 13 mg/L). Blood pressure is 95/50 mmHg. 1. What are the possible explanations for her presentation? Laboratory tests demonstrate hepatocellular necrosis (AST 21,000 U/L) and coagulopathy (INR 9.1) with thrombocytopenia (platelet count 26 x 109/L). Acute liver failure appears the most likely diagnosis. 2. What are the most likely causes of acute liver failure (ALF) in this previously well patient? Her mean arterial blood pressure remains low (50mmHg) after 3 litres of colloid and crystalloid. The casualty nurse, who is doing half-hourly neurological observations, reports reduced pupillary response to light. 3. What severe complications of ALF may result in death within hours, and what are the immediate management priorities for this patient? Introduction Successful management of this rare but potentially devastating disorder relies on early recognition. The hallmark of acute liver failure (ALF) is encephalopathy (ranging from a subtle alterations in consciousness level to coma) in the context of an acute, severe liver injury. -

Mass/Multiple Casualty Triage

9.1 MASS/MULTIPLE CASUALTY TRIAGE PURPOSE · The goal of the mass/multiple Casualty Triage protocol is to prepare for a unified, coordinated, and immediate EMS mutual aid response by prehospital and hospital agencies to effectively expedite the emergency management of the victims of any type of Mass Casualty Incident (MCI). · Successful management of any MCI depends upon the effective cooperation, organization, and planning among health care professionals, hospital administrators and out-of-hospital EMS agencies, state and local government representatives, and individuals and/or organizations associated with disaster-related support agencies. · Adoption of Model Uniform Core Criteria (MUCC). DEFINITIONS Multiple Casualty Situations · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries do not exceed the ability of the provider to render care. Patients with life-threatening injuries are treated first. Mass Casualty Incidents · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries exceed the capability of the provider, and patients sustaining major injuries who have the greatest chance of survival with the least expenditure of time, equipment, supplies, and personnel are managed first. H a z GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS m Initial assessment to include the following: a t · Location of incident. & · Type of incident. M · Any hazards. C · Approximate number of victims. I · Type of assistance required. 9 . 1 COMMUNICATION · Within the scope of a Mass Casualty Incident, the EMS provider may, within the limits of their scope of practice, perform necessary ALS procedures, that under normal circumstances would require a direct physician’s order. · These procedures shall be the minimum necessary to prevent the loss of life or the critical deterioration of a patient’s condition. -

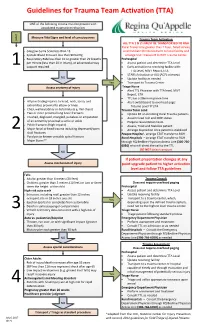

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

Validation of Lactate Clearance at 6 H for Mortality Prediction in Critically Ill Children

570 Research Article Validation of lactate clearance at 6 h for mortality prediction in critically ill children Rajeev Kumar, Nirmal Kumar Background and Aims: To validate the lactate clearance (LC) at 6 h for mortality Access this article online prediction in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU)-admitted patients and its comparison Website: www.ijccm.org with a pediatric index of mortality 2 (PIM 2) score. Design: A prospective, observational DOI: 10.4103/0972-5229.192040 study in a tertiary care center. Materials and Methods: Children <13 years of age, Quick Response Code: Abstract admitted to PICU were included in the study. Lactate levels were measured at 0 and 6 h of admission for clearance. LC and delayed or nonclearance group compared for in-hospital mortality and compared with PIM 2 score for mortality prediction. Results: Of the 140 children (mean age 33.42 months) who were admitted to PICU, 23 (16.42%) patients died. For LC cut-off (16.435%) at 6 h, 92 patients qualified for clearance and 48 for delayed or non-LC group. High mortality was observed (39.6%) in delayed or non-LC group as compared to clearance group (4.3%) (P = 0.000). LC cut-off of 16.435% at 6 h (sensitivity 82.6%, specificity 75.2%, positive predictive value 39.6%, and negative predictive value 95.7%) correlates with mortality. Area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) for LC at 6 h for mortality prediction was 0.823 (P = 0.000). The area under ROC curve for expected mortality prediction by PIM 2 score at admission was 0.906 and at 12.3% cut-off of PIM 2 Score was related with mortality. -

Package for Emergency Resuscitation and Intensive Care Unit

Package for Emergency Resuscitation and Intensive Care Unit Extracted from WHO manual Surgical Care at the District Hospital and WHO Integrated Management for Emergency & Essential Surgical Care toolkit For further details and anaesthetic resources please refer to full text at: http://www.who.int/surgery/publications/imeesc/en/index.html 1 1. Anaesthesia and Oxygen XYGEN KEY POINTS: • A reliable oxygen supply is essential for anaesthesia and for any seriously ill patients • In many places, oxygen concentrators are the most suitable and economical way of providing oxygen, with a few backup cylinders in case of electricity failure • Whatever your source of oxygen, you need an effective system for maintenance and spares • Clinical staff need to be trained how to use oxygen safely, effectively and economically. • A high concentration of oxygen is needed during and after anaesthesia: • If the patient is very young, old, sick, or anaemic • If agents that cause cardio-respiratory depression, such as halothane, are used. Air already contains 20.9% oxygen, so oxygen enrichment with a draw-over system is a very economical method of providing oxygen. Adding only 1 litre per minute may increase the oxygen concentration in the inspired gas to 35–40%. With oxygen enrichment at 5 litres per minute, a concentration of 80% may be achieved. Industrial-grade oxygen, such as that used for welding, is perfectly acceptable for the enrichment of a draw-over system and has been widely used for this purpose. Oxygen Sources In practice, there are two possible sources of oxygen for medical purposes: • Cylinders: derived from liquid oxygen • Concentrators: which separate oxygen from air. -

Anytown Trauma Center Trauma Protocols

ANYTOWN TRAUMA CENTER TRAUMA PROTOCOLS TITLE: TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTOCOL PURPOSE: The purpose of the protocol is to establish guidelines for trauma team activation and define the members of the responding trauma team to facilitate the resuscitation and management of critical or seriously injured patients who require rapid, organized resuscitation, evaluation and stabilization to promote optimal outcomes. It also serves to provide triage guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. PROCESS: 1. TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTCOL A. The criteria for activation of the trauma team is clearly defined and posted at the Emergency Department triage desk, by the EMS communication station and in the resuscitation rooms. B. The trauma team may be activated prior to arrival based on the EMS communication and their assessment. C. The trauma surgeon, emergency medicine physician, emergency department charge nurse/ house supervisor, emergency department nurses and the Trauma Program Manager may activate the trauma team. D. The person calling the trauma activation will initiate the trauma page to group page the trauma team and will specify the MOI, BP, HR, ETA and level of activation required and age if available. E. If the trauma team members are present in the emergency department and alert is still communicated to ensure everyone is notified. F. Trauma team member notification and arrival times will be documented on the trauma flow sheet (paper or electronic). G. Trauma team members will sign-in when they arrive. H. Trauma team members will be activated for all patients who meet the following criteria: 1. Level 1 trauma activation (major): life threatening injuries and/or unstable vital signs, limb-threating or disability threatening injury 2. -

A Uniform Triage Scale in Emergency Medicine Information Paper

A Uniform Triage Scale in Emergency Medicine Information Paper Triage: sorting, sifting (Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary) from the French verb trier- “to sort.” Triage has long been considered a simple frontline sorting mechanism in hospital-based emergency departments (EDs). However, evolution in the practice of emergency medicine during the past two decades necessitates a change in how this entry point process is performed and utilized. Many triage systems are in use in the US, but there is no uniform triage scale that would facilitate the development of operational standards in EDs. A nationally standardized triage scale would provide an analytic basis for determining whether the health care system provides safe access to emergency care based on design, resources, and utilization. The performance of EDs could be compared based on case mix and acuity, and expected standards for facilities could be defined. Planners and policy makers would have the tools and the data needed to make rational improvements in the health care delivery system. This paper on triage will acquaint the reader with the history of triage, and provide an overview of the Australian and Canadian systems which are already in use on a national level. The reliability of triage is addressed, and the Canadian and Australian scales are compared. Future implications for a national triage scale are described, along with the goals and benefits of triage development. While there is some controversy about potential liability issues, the many advantages of a national triage scale appear to outweigh any potential disadvantages. History of triage The first medical application of triage occurred on the French battlefield where sorting the victims determined who would be left behind. -

Severe Localized Scapular Pain After a Strenuous Weight-Lifting Session

CASE REPORT Severe localized scapular Editor’s key points With the rising popularity of ultra- pain after a strenuous distance endurance events, strength and conditioning programs, and obstacle course races, exertional weight-lifting session rhabdomyolysis (ER) has become increasingly common in sporting Rosamond E. Lougheed Simpson MD MSc CCFP(SEM) DipSportMed communities. Steven R. Joseph MD MA CCFP(SEM) DipSportMed Lisa Fischer MD CCFP(SEM) FCFP DipSportMed Exertional rhabdomyolysis is often characterized by the classic triad habdomyolysis is a medical condition whereby the intracellular con- of generalized weakness, myalgia, tents from damaged skeletal muscle tissues are released into the blood, and myoglobinuria; however, it is critical to recognize that many cases causing myriad clinical symptoms and outcomes. These can range will not present with all 3 of these Rfrom muscle pain to compartment syndrome, end-organ failure, and death.1-3 criteria. For the male patient in this While the triggers of rhabdomyolysis are numerous, physical exertion as a report, severe myalgia was his only presenting symptom from the triad. causal factor has been receiving increasing media attention recently.4-7 The incidence of exertional rhabdomyolysis (ER) has been challenging The ability to recognize ER, stratify 8 patients into low- and high-risk to estimate, as many cases are likely underrecognized. Current incidence categories, and understand how estimates range from 22.2 to 29.9 per 100 000 patients a year.9,10 As ultra- risk affects patients’ return to play distance endurance events, strength and conditioning programs (eg, CrossFit), can help family physicians make treatment, referral, and return- and obstacle course races have become wildly popular with the superfit to-play decisions with increased and weekend warriors alike, ER is being increasingly recognized as common confidence. -

Redefining the Trauma Triage Matrix

journalofsurgicalresearch july 2020 (251) 195e201 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: www.JournalofSurgicalResearch.com Redefining the Trauma Triage Matrix: The Role of Emergent Interventions Rachel S. Morris, MD,a,* Nicholas J. Davis, MD,b Amy Koestner, MSN,c Lena M. Napolitano, MD,d Mark R. Hemmila, MD,d and Christopher J. Tignanelli, MDa,b,e a Department of Surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota b Department of Surgery, North Memorial Medical Center, Robbinsdale, Minnesota c Department of Surgery, Spectrum Health - Butterworth Hospital, Grand Rapids, Michigan d Department of Surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan e Institute for Health Informatics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota article info abstract Article history: Background: A tiered trauma team activation (TTA) system aims to allocate resources pro- Received 10 July 2019 portional to the patient’s need based upon injury burden. The current metrics used to Received in revised form evaluate appropriateness of TTA are the trauma triage matrix (TTM), need for trauma 22 October 2019 intervention (NFTI), and secondary triage assessment tool (STAT). Accepted 2 November 2019 Materials and methods: In this retrospective study, we compared the effectiveness of the Available online xxx need for an emergent intervention within 6 h (NEI-6) with existing definitions. Data from the Michigan Trauma Quality Improvement Program was utilized. The dataset contains Keywords: information from 31 level 1 and 2 trauma centers from 2011 to 2017. Inclusion criteria were: Activation adult patients (16 y) and ISS 5. Trauma Results: 73,818 patients were included in the study. Thirty percentage of trauma patients Triage met criteria for STAT, 21% for NFTI, 20% for TTM, and 13% for NEI-6. -

Central Venous Catheter (CVC) Placement

Medical Education Policy: Central Venous Catheter (CVC) Placement Facility: CMC Origin Date: June 2015 Revision Date: March 2019 Sponsor: GMEC 1. PURPOSE: Carilion Clinic is committed to excellent patient care, with the highest priority towards patient safety and excellent clinical outcomes. As a graduate medical education training site, Carilion Clinic will standardize the basic education, competency assessment, supervision and procedural methods for medical students, resident physicians and fellows inserting central venous catheters (CVCs) under this policy. This policy will guide the education of trainees in the use of proper sterile technique, anatomical landmarks and ultrasound guidance when inserting CVCs. The CVCs covered by this policy are all percutaneously inserted central catheters including large bore central catheters such as dialysis and resuscitation catheters. This policy supports the routine use of ultrasound guidance for internal jugular and femoral venous sites of CVC placement unless the clinical urgency and/or immediate unavailability of ultrasound precludes sonographic guidance. At times, extraordinary clinical circumstances or clinical judgment of the attending physician may dictate that different approaches to central line placement may be utilized. It is expected that these will be an unusual occurrences. 2. SCOPE: This policy outlines the education, training and supervision of all trainees involved in CVC insertion. All postgraduate medical trainees performing CVC placement in their clinical duties will be trained in anatomic landmarks and ultrasound guided CVC insertion techniques as appropriate to location. This policy designates the minimum standard by which a resident or fellow will be educated to place CVCs, when they may place central lines WITHOUT direct supervision, and who may supervise and teach central line placement. -

Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) Response Module 1

Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) Response Module 1 (Hamilton County Fire Chief's Association, 2013) 1 Objectives Purpose: This module will educate staff on mass casualty triage incident response, including how to: • Define mass casualty triage • Determine considerations for adults and pediatrics • Understand the importance of a patient tracking system • Recognize and implement the patient admission/ discharge MCI triage process • Determine how to appropriately handle the deceased in a large-scale MCI • Recognize the range of incidents that may cause MCIs 2 MCI Basics 3 What is an MCI? • A mass casualty incident (MCI) is an incident where the number of patients exceeds the amount of healthcare resources available. • This number varies widely across the country, but is typically greater than 10 patients. 4 Types of MCI Notifications • During a large scale incident such as a mass casualty, it is important to have a mass notification system. Successful mass notification systems will: . Internally: alert staff to activate MCI protocols and prepare for a potential surge of patients . Externally: increase community awareness 5 Assisting in MCI Response Considerations for hospital staff in an MCI: • Some patients may arrive to the hospital without having been assessed/ triaged at the scene • MCI response requires efficiency and coordination • Non-clinical personnel (including hospital volunteers) can assist in moving patients to designated areas based on level of care • Help gather patient information in the emergency treatment area • Staff should review patients in clinical assignment for any potential discharges/ transfers to make room for potential MCI admissions, a process known as “surge discharge” (Chung S, 2019) 6 Triage Basics Definition of MCI Triage Triage means “to sort.” Triage in an MCI is the assignment of resources based on the initial patient assessment and consideration of available resources.