Trauma Patient Triage Definitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rare Case of Penetrating Trauma of Frontal Sinus with Anterior Table Fracture Himanshu Raval1*, Mona Bhatt2 and Nihar Gaur3

ISSN: 2643-4474 Raval et al. Neurosurg Cases Rev 2020, 3:046 DOI: 10.23937/2643-4474/1710046 Volume 3 | Issue 2 Neurosurgery - Cases and Reviews Open Access CASE REPORT Case Report: A Rare Case of Penetrating Trauma of Frontal Sinus with Anterior Table Fracture Himanshu Raval1*, Mona Bhatt2 and Nihar Gaur3 1 Department of Neurosurgery, NHL Municipal Medical College, SVP Hospital Campus, Gujarat, India Check for updates 2Medical Officer, CHC Dolasa, Gujarat, India 3GAIMS-GK General Hospital, Gujarat, India *Corresponding author: Dr. Himanshu Raval, Resident, Department of Neurosurgery, NHL Municipal Medical College, SVP Hospital Campus, Elisbridge, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380006, India, Tel: 942-955-3329 Abstract Introduction Background: Head injury is common component of any Road traffic accident (RTA) is the most common road traffic accident injury. Injury involving only frontal sinus cause of cranio-facial injury and involvement of frontal is uncommon and unique as its management algorithm is bone fractures are rare and constitute 5-9% of only fa- changing over time with development of radiological modal- ities as well as endoscopic intervention. Frontal sinus inju- cial trauma. The degree of association has been report- ries may range from isolated anterior table fractures causing ed to be 95% with fractures of the anterior table or wall a simple aesthetic deformity to complex fractures involving of the frontal sinuses, 60% with the orbital rims, and the frontal recess, orbits, skull base, and intracranial con- 60% with complex injuries of the naso-orbital-ethmoid tents. Only anterior table injury of frontal sinus is rare in pen- region, 33% with other orbital wall fractures and 27% etrating head injury without underlying brain injury with his- tory of unconsciousness and questionable convulsion which with Le Fort level fractures. -

Traumatic Brain Injury

REPORT TO CONGRESS Traumatic Brain Injury In the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation Submitted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention The Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation is a publication of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH Director, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Debra Houry, MD, MPH Director, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Grant Baldwin, PhD, MPH Director, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention The inclusion of individuals, programs, or organizations in this report does not constitute endorsement by the Federal government of the United States or the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Atlanta, GA. Executive Summary . 1 Introduction. 2 Classification . 2 Public Health Impact . 2 TBI Health Effects . 3 Effectiveness of TBI Outcome Measures . 3 Contents Factors Influencing Outcomes . 4 Effectiveness of TBI Rehabilitation . 4 Cognitive Rehabilitation . 5 Physical Rehabilitation . 5 Recommendations . 6 Conclusion . 9 Background . 11 Introduction . 12 Purpose . 12 Method . 13 Section I: Epidemiology and Consequences of TBI in the United States . 15 Definition of TBI . 15 Characteristics of TBI . 16 Injury Severity Classification of TBI . 17 Health and Other Effects of TBI . -

5 Things to Know About Traumatic Brain Injuries

5 Things to Know About Traumatic Brain Injuries What is a Traumatic Brain Injury? A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined as a blow or jolt to the head or a penetrating head injury that disrupts the function of the brain. The severity of such an injury may range from: “mild” – i.e., a brief change in mental status or consciousness, to “severe” – i.e., an extended period of unconsciousness or amnesia after the injury. What Causes a Traumatic Brain Injury? A TBI occurs when an outside force impacts the head hard enough to cause the brain to move within the skull, or if the force causes the skull to break and directly hurts the brain. Rapid acceleration/deceleration of the head can also force the brain the move back and forth inside the skull, which pulls apart nerve fibers and causes damage to brain tissue. The most common causes of TBI are: Falls Motor vehicle-traffic crashes Physical violence Sports accidents What are the symptoms of a TBI? A person with a brain injury can experience a variety of symptoms, but not necessarily all of the following symptoms: Lethargy (sluggish, sleepy, gets tired easily) Continuous headache Confusion Ringing in the ears, or changes in ability to hear Vision changes (blurred vision, seeing double, light-sensitive) Dilated pupils Difficulty thinking (memory problems, poor judgment, poor attention span, slow thought process) Dizziness or balance problems Inappropriate emotional responses (irritability, easily frustrated, inappropriate crying or laughing) Difficulty speaking (slurred speech) Respiratory problems (slow or uneven breathing) Vomiting Body numbness or tingling Paralysis (difficulty moving body parts, weakness, poor coordination) Semi-comatose (not alert and unable to respond to others) Loss of consciousness Who is at Highest Risk for TBI? The two age groups at the highest first for TBI are 0-4 year olds and 15-19 year olds. -

Penetrating Injury to the Head: Case Reviews K Regunath, S Awang*, S B Siti, M R Premananda, W M Tan, R H Haron**

CASE REPORT Penetrating Injury to the Head: Case Reviews K Regunath, S Awang*, S B Siti, M R Premananda, W M Tan, R H Haron** *Department of Neurosciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 16150 Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, **Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Kuala Lumpur the right frontal lobe to a depth of approximately 2.5cm. SUMMARY (Figure 1: A & B) There was no obvious intracranial Penetrating injury to the head is considered a form of severe haemorrhage along the track of injury. The patient was taken traumatic brain injury. Although uncommon, most to the operating theatre and was put under general neurosurgical centres would have experienced treating anaesthesia. The nail was cut proximal to the entry wound patients with such an injury. Despite the presence of well and the piece of wood removed. The entry wound was found written guidelines for managing these cases, surgical to be contaminated with hair and debris. The nail was also treatment requires an individualized approach tailored to rusty. A bicoronal skin incision was fashioned centred on the the situation at hand. We describe a collection of three cases entry wound. A bifrontal craniotomy was fashioned and the of non-missile penetrating head injury which were managed bone flap removed sparing a small island of bone around the in two main Neurosurgical centres within Malaysia and the nail (Figure 1: C&D). Bilateral “U” shaped dural incisions unique management approaches for each of these cases. were made with the base to the midline. The nail was found to have penetrated with dura about 0.5cm from the edge of KEY WORDS: Penetrating head injury, nail related injury, atypical penetrating the sagittal sinus. -

Mass/Multiple Casualty Triage

9.1 MASS/MULTIPLE CASUALTY TRIAGE PURPOSE · The goal of the mass/multiple Casualty Triage protocol is to prepare for a unified, coordinated, and immediate EMS mutual aid response by prehospital and hospital agencies to effectively expedite the emergency management of the victims of any type of Mass Casualty Incident (MCI). · Successful management of any MCI depends upon the effective cooperation, organization, and planning among health care professionals, hospital administrators and out-of-hospital EMS agencies, state and local government representatives, and individuals and/or organizations associated with disaster-related support agencies. · Adoption of Model Uniform Core Criteria (MUCC). DEFINITIONS Multiple Casualty Situations · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries do not exceed the ability of the provider to render care. Patients with life-threatening injuries are treated first. Mass Casualty Incidents · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries exceed the capability of the provider, and patients sustaining major injuries who have the greatest chance of survival with the least expenditure of time, equipment, supplies, and personnel are managed first. H a z GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS m Initial assessment to include the following: a t · Location of incident. & · Type of incident. M · Any hazards. C · Approximate number of victims. I · Type of assistance required. 9 . 1 COMMUNICATION · Within the scope of a Mass Casualty Incident, the EMS provider may, within the limits of their scope of practice, perform necessary ALS procedures, that under normal circumstances would require a direct physician’s order. · These procedures shall be the minimum necessary to prevent the loss of life or the critical deterioration of a patient’s condition. -

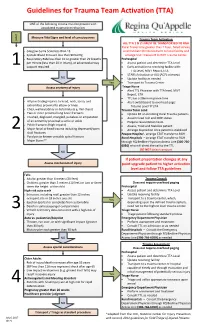

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

Traumatic Brain Injury(Tbi)

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY(TBI) B.K NANDA, LECTURER(PHYSIOTHERAPY) S. K. HALDAR, SR. OCCUPATIONAL THERAPIST CUM JR. LECTURER What is Traumatic Brain injury? Traumatic brain injury is defined as damage to the brain resulting from external mechanical force, such as rapid acceleration or deceleration impact, blast waves, or penetration by a projectile, leading to temporary or permanent impairment of brain function. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has a dramatic impact on the health of the nation: it accounts for 15–20% of deaths in people aged 5–35 yr old, and is responsible for 1% of all adult deaths. TBI is a major cause of death and disability worldwide, especially in children and young adults. Males sustain traumatic brain injuries more frequently than do females. Approximately 1.4 million people in the UK suffer a head injury every year, resulting in nearly 150 000 hospital admissions per year. Of these, approximately 3500 patients require admission to ICU. The overall mortality in severe TBI, defined as a post-resuscitation Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) ≤8, is 23%. In addition to the high mortality, approximately 60% of survivors have significant ongoing deficits including cognitive competency, major activity, and leisure and recreation. This has a severe financial, emotional, and social impact on survivors left with lifelong disability and on their families. It is well established that the major determinant of outcome from TBI is the severity of the primary injury, which is irreversible. However, secondary injury, primarily cerebral ischaemia, occurring in the post-injury phase, may be due to intracranial hypertension, systemic hypotension, hypoxia, hyperpyrexia, hypocapnia and hypoglycaemia, all of which have been shown to independently worsen survival after TBI. -

Identification of Pelvic Fragility Fractures at a University Teaching Hospital

10.7861/clinmed.20-2-s113 RESEARCH The truth behind the pubic rami fracture: identification of pelvic fragility fractures at a university teaching hospital Authors: Dawn van Berkel,A Orly Herschkovich,A Rachael Taylor,A Terence OngA and Opinder SahotaA Introduction Furthermore, 23 patients had acute pelvic fragility fractures identified on CT or MRI, in the presence of normal X-rays. In Older patients presenting on the acute medical take with pelvic these patients, further imaging showed that 70% had suffered fragility fractures (PFF) represent an increasing epidemic.1 The pubic rami fractures, 22% acetabular fractures, 74% sacral most common pelvic fracture identified by plain X-ray is that of the fractures and 22% ilium fractures. pubic rami.2 PFF are painful and despite optimal analgesia, many of these patients struggle to mobilise. Between 60% and 80% of patients have fractures of the posterior pelvic ring, namely of the Conclusion 3,4 sacrum, which are overlooked and not visible on plain X-ray. Pubic rami fragility fractures are a significant problem in Sacral fractures are unstable and load-bearing, thus increasing older people and often require admission to hospital. Further the likelihood of pain-dependent mobility reduction and the imaging confirms that these fractures are complex, with 5 risks that this poses in an older population. Minimally invasive co-existing fractures of the acetabulum and sacrum being sacroplasty is available and has been shown to improve pain- common. Findings also confirm that plain X-rays are a poor 6,7 related outcomes. We aimed to quantify the number of patients modality in the identification of pelvic fractures. -

12 Fractures of the Pelvis 239 12 Fractures of the Pelvis

12 Fractures of the Pelvis 239 12 Fractures of the Pelvis M. Tile tions, the results with simple treatment will be quite 12.1 different (Fig. 12.1). Therefore, in reading the litera- Introduction ture, we must be certain that we are not comparing apples with oranges or chalk with cheese. An under- In the past two decades, traumatic disruption of the standing of this injury is the key to logical decision pelvic ring has become a major focus of orthopedic making. interest, as has the care of polytraumatized patients. This injury forms part of the spectrum of polytrauma and must be considered a potentially lethal injury with mortality rates of 10%–20%. The stabilization 12.2 of the unstable pelvic ring in the acute resuscita- Understanding the Injury tion of multiply injured patients is now conventional wisdom. In order to better understand our proposed classi- With respect to the long-term results of pelvic fication and rationale of management, some knowl- trauma, conventional orthopedic wisdom held that edge of pelvic biomechanics is essential. surviving patients with disruptions of the pelvic ring The pelvis is a ring structure made up of two recovered well clinically from their musculoskeletal innominate bones and the sacrum. These bones have injury. However, the literature on pelvic trauma was no inherent stability, and the stability of the pelvic ring mostly concerned with life-threatening problems is thus due mainly to its surrounding soft tissues. and paid scant attention to the late musculoskeletal The stabilizing structures of the pelvic ring are the problems reported in a handful of articles published symphysis pubis, the posterior sacroiliac complex, prior to 1980. -

A Uniform Triage Scale in Emergency Medicine Information Paper

A Uniform Triage Scale in Emergency Medicine Information Paper Triage: sorting, sifting (Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary) from the French verb trier- “to sort.” Triage has long been considered a simple frontline sorting mechanism in hospital-based emergency departments (EDs). However, evolution in the practice of emergency medicine during the past two decades necessitates a change in how this entry point process is performed and utilized. Many triage systems are in use in the US, but there is no uniform triage scale that would facilitate the development of operational standards in EDs. A nationally standardized triage scale would provide an analytic basis for determining whether the health care system provides safe access to emergency care based on design, resources, and utilization. The performance of EDs could be compared based on case mix and acuity, and expected standards for facilities could be defined. Planners and policy makers would have the tools and the data needed to make rational improvements in the health care delivery system. This paper on triage will acquaint the reader with the history of triage, and provide an overview of the Australian and Canadian systems which are already in use on a national level. The reliability of triage is addressed, and the Canadian and Australian scales are compared. Future implications for a national triage scale are described, along with the goals and benefits of triage development. While there is some controversy about potential liability issues, the many advantages of a national triage scale appear to outweigh any potential disadvantages. History of triage The first medical application of triage occurred on the French battlefield where sorting the victims determined who would be left behind. -

Pelvic Trauma: WSES Classification and Guidelines Federico Coccolini1*, Philip F

Coccolini et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2017) 12:5 DOI 10.1186/s13017-017-0117-6 REVIEW Open Access Pelvic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines Federico Coccolini1*, Philip F. Stahel2, Giulia Montori1, Walter Biffl3, Tal M Horer4, Fausto Catena5, Yoram Kluger6, Ernest E. Moore7, Andrew B. Peitzman8, Rao Ivatury9, Raul Coimbra10, Gustavo Pereira Fraga11, Bruno Pereira11, Sandro Rizoli12, Andrew Kirkpatrick13, Ari Leppaniemi14, Roberto Manfredi1, Stefano Magnone1, Osvaldo Chiara15, Leonardo Solaini1, Marco Ceresoli1, Niccolò Allievi1, Catherine Arvieux16, George Velmahos17, Zsolt Balogh18, Noel Naidoo19, Dieter Weber20, Fikri Abu-Zidan21, Massimo Sartelli22 and Luca Ansaloni1 Abstract Complex pelvic injuries are among the most dangerous and deadly trauma related lesions. Different classification systems exist, some are based on the mechanism of injury, some on anatomic patterns and some are focusing on the resulting instability requiring operative fixation. The optimal treatment strategy, however, should keep into consideration the hemodynamic status, the anatomic impairment of pelvic ring function and the associated injuries. The management of pelvic trauma patients aims definitively to restore the homeostasis and the normal physiopathology associated to the mechanical stability of the pelvic ring. Thus the management of pelvic trauma must be multidisciplinary and should be ultimately based on the physiology of the patient and the anatomy of the injury. This paper presents the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) classification of pelvic trauma and the management Guidelines. Keywords: Pelvic, Trauma, Management, Guidelines, Mechanic, Injury, Angiography, REBOA, ABO, Preperitoneal pelvic packing, External fixation, Internal fixation, X-ray, Pelvic ring fractures Background At present no comprehensive guidelines have been Pelvic trauma (PT) is one of the most complex manage- published about these issues.