A Uniform Triage Scale in Emergency Medicine Information Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency Physician Recognition of Adverse Drug-Related Events in Elder Patients Presenting to an Emergency Department

ACAD EMERG MED d March 2005, Vol. 12, No. 3 d www.aemj.org 197 Emergency Physician Recognition of Adverse Drug-related Events in Elder Patients Presenting to an Emergency Department Corinne Miche` le Hohl, MD, CCFP, FRCPC, Caroline Robitaille, BPharm, MSc, Vicky Lord, BPharm, MSc, Jerrald Dankoff, MD, CSPQ, Antoinette Colacone, BSc, CCRA, Luc Pham, BSc, Anick Be´ rard, PhD, Jocelyne Pe´ pin,BPharm,MSc,MarcAfilalo,MD,FRCPC Abstract Objectives: The authors examined the ability of emergency ADREs that were not associated with the chief complaint physicians (EPs) to recognize adverse drug-related events (32.1%; 95% CI = 14.8% to 49%). EPs recognized six of seven (ADREs) in elder patients presenting to the emergency severe ADREs (85.7%), 13 of 23 moderate ADREs (56.5%; department (ED). Methods: This was a prospective obser- 95% CI = 36.8% to 77%), and none of the mild ADREs. vational study of patients at least 65 years of age who Recognition of ADREs varied with medication class. presented to the ED. ADREs were identified using a vali- Conclusions: EP performance was superior at identifying dated, standardized scoring system. EP recognition of severe ADREs relating to the patients’ chief complaints. ADREs was assessed through physician interview and However, EP performance was suboptimal with respect to subsequent chart review. Results: A total of 161 patients identifying ADREs of lower severity, having missed a signif- were enrolled in the study. Thirty-seven ADREs were icant number of ADREs of moderate severity as well as ones identified, which occurred in 26 patients (16.2%; 95% unrelated to the patients’ chief complaints. -

Advanced Trauma Management for Emergency Physicians: Updates

The Institute for Emergency Department Clinical Quality Improvement Advanced Trauma Management for Emergency Physicians: www.EDQualityInstitute.org Updates and Best Practices 14-15 December, 2020 Interactive CME Course – Live Streamed from Boston The Institute for Emergency Department Clinical Quality Improvement Promoting excellence in emergency department operations, clinical quality, and patient safety through a commitment to quality improvement, clinical education, international collaboration, and research Offered by BIDMC Department of Emergency Medicine, a Harvard Medical School teaching hospital Course Description Advanced Trauma Management for the Emergency Physician is a 2-day, 13-hour course that provides updates, best practices, and new pathways & protocols regarding the acute care of major trauma patients, from Emergency Department arrival through hospital admission/discharge. The course will focus on advanced, state-of- the-art clinical knowledge and skills, with an emphasis on teamwork, non-technical skills, and best practices in ED management. The goal of this advanced trauma management course is to prepare emergency clinicians, who already have a strong base in trauma care, to quickly and accurately assess and provide high-quality care for trauma patients. Emphasis will be on optimizing outcomes for patients presenting with high-risk traumatic injuries. Advanced Trauma Management for the Emergency Physician is delivered by the Department of Emergency Medicine at Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a level 1 trauma center. This course is relevant for clinicians working in emergency medicine, critical care, and urgent care and can be applied in the trauma center, community hospital, or remote setting. Optimized for Remote Education The program is optimized for distance learning. -

Tracheal Intubation Following Traumatic Injury)

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT UPDATE The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care Guidelines for Emergency Tracheal Intubation Immediately after Traumatic Injury C. Michael Dunham, MD, Robert D. Barraco, MD, David E. Clark, MD, Brian J. Daley, MD, Frank E. Davis III, MD, Michael A. Gibbs, MD, Thomas Knuth, MD, Peter B. Letarte, MD, Fred A. Luchette, MD, Laurel Omert, MD, Leonard J. Weireter, MD, and Charles E. Wiles III, MD for the EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group J Trauma. 2003;55:162–179. REFERRALS TO THE EAST WEB SITE and impaired laryngeal reflexes are nonhypercarbic hypox- Because of the large size of the guidelines, specific emia and aspiration, respectively. Airway obstruction can sections have been deleted from this article, but are available occur with cervical spine injury, severe cognitive impairment on the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score Յ 8), severe neck injury, Web site (www.east.org/trauma practice guidelines/Emergency severe maxillofacial injury, or smoke inhalation. Hypoventi- Tracheal Intubation Following Traumatic Injury). lation can be found with airway obstruction, cardiac arrest, severe cognitive impairment, or cervical spinal cord injury. I. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM Aspiration is likely to occur with cardiac arrest, severe cog- ypoxia and obstruction of the airway are linked to nitive impairment, or severe maxillofacial injury. A major preventable and potentially preventable acute trauma clinical concern with thoracic injury is the development of Hdeaths.1–4 There is substantial documentation that hyp- nonhypercarbic hypoxemia. Lung injury and nonhypercarbic oxia is common in severe brain injury and worsens neuro- hypoxemia are also potential sequelae of aspiration. -

Emergency Department Resuscitation of the Critically Ill Review by Stephen C

BOOK AND MEDIA REVIEW Emergency Department Resuscitation of the Critically Ill Review by Stephen C. Morris, MD, MPH 0196-0644/$-see front matter Copyright © 2018 by the American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency Department Resuscitation of the crashing morbidly obese patient reviews some of the nuanced Critically Ill management we should be striving for as more of our patients become obese, such as specific airway and ventilation Winters ME, Bond MC, Marcolini EG, et al management and use of ideal versus total body weight American College of Emergency Physicians calculations for critical-care-specific medications. Consider It was with great pleasure that I agreed to review the another example from the chapter on left ventricular assist second edition of Emergency Department Resuscitation of the devices. Although these patients have long been the domain Critically Ill, by Michael E. Winters. I had read and relied of specialty centers, with complex physiology and on the first edition posttraining. Like most who work in complications, the longevity now offered by the devices will emergency medicine, I practice a great deal of critical care; ultimately make them the domain of the community however, I have not completed a fellowship in critical care, emergency department. Additionally, at the cutting edge of nor do I review critical care literature with the level of our practice, the text contains a chapter on extracorporeal scrutiny that I would like. For those of us who want to membrane oxygenation, with a discussion of the practical ensure that we are up to date to guarantee clinical and clinical aspects of implementation. -

Implementing Public-Access Programs for Automated External Defibrillation

Correspondance that approving new drugs more rapidly Therapeutic Products Program internal constitute only 4.6% of drugs ap- does not compromise safety, we are processes was 188 days (range 74–376 proved in the United States at least 1 better off putting our limited resources days).2 Approval times are much longer year before approval in Canada in the into other areas such as improving for 2 reasons: considerable downtime 7-year period. Canada’s woefully inadequate postmar- occurs between the receipt of the appli- Finally, I endorse the recommen- keting evaluation system. cation and the start of the scientific re- dation that Canada’s inadequate post- view, and the separate assessment of marketing surveillance system should Joel Lexchin manufacturing and stability data is often be improved and have proposed new Emergency physician not coordinated with the safety and effi- approaches that could be adopted in University Health Network cacy evaluation. Canada.5–7 However, the unnecessary Toronto, Ont. An evaluation of the importance of a delays in Canada’s review and ap- Barbara Mintzes new drug’s therapeutic potential should proval system should also be elimi- Department of Health Care be based not simply on the lack of a nated and Canada’s performance stan- & Epidemiology current treatment, which is the practice dard of 355 days for all new drug University of British Columbia of the Patented Medicine Prices Re- applications achieved. In that way, Vancouver, BC view Board, but rather it should be Canadians will no longer have to ex- based on several factors. The US Food perience delayed access to potentially References 1. -

Emergency Medicine Profile

Emergency Medicine Profile Updated December 2019 1 Table of Contents Slide . General Information 3-6 . Total number & number/100,000 population by province, 2019 7 . Number/100,000 population, 1995-2019 8 . Number by gender & year, 1995-2019 9 . Percentage by gender & age, 2019 10 . Number by gender & age, 2019 11 . Percentage by main work setting, 2019 12 . Percentage by practice organization, 2017 13 . Hours worked per week (excluding on-call), 2019 14 . On-call duty hours per month, 2019 15 . Percentage by remuneration method 16 . Professional & work-life balance satisfaction, 2019 17 . Number of retirees during the three year period of 2016-2018 18 . Employment situation, 2017 19 . Links to additional resources 20 2 General information Emergency medicine focuses on the recognition, evaluation and care of patients who are acutely ill or injured. It is a high-pressure, fast-paced specialty that, because of its diversity, requires a broad base of medical knowledge and a variety of well-honed clinical and technical skills. Emergency physicians (emergentologists) must be prepared to treat patients of all ages and a nearly infinite variety of conditions and degrees of illness – often before a definite diagnosis is made and within time-restricted circumstances. The approach to treatment in an emergency department can vary dramatically from case to case, even for the same medical condition, depending on whether it’s a pediatric patient versus a geriatric patient. Emergency physicians need a number of personal strengths, including physical and emotional toughness, confidence, composure, ability to multi task and strong interpersonal skills. They must also be willing and able to do shift work. -

The Nebraska Office of Emergency Health Systems Trauma Program Is Pleased That You Wish to Participate in the Statewide Trauma System

Revised July 2019 INSTRUCTIONS FOR FILLING OUT PRE-REVIEW QUESTIONNAIRE (PRQ) The Nebraska Office of Emergency Health Systems Trauma Program is pleased that you wish to participate in the statewide trauma system. The Nebraska Statewide Trauma System is comprised of hospitals and clinics striving to improve trauma patient care. Through this system all facilities offering trauma care may become centers of excellence. Thank you for participating in this process. In order to prepare for your on-site review, please complete this questionnaire. All answers should directly follow the questions. The entire questionnaire is available on the web in a downloadable format @ http://dhhs.ne.gov/Pages/EHS-Statewide-Trauma-System-of-Care.aspx. The PRQ should be completed electronically if possible otherwise, you may submit a hard copy. Note: If a hard copy is printed a color printer should be used so that information and questions printed in blue appear on the page to the applicant. Return the completed questionnaire to: Sherri Wren EHS Trauma Program Manager Office of Emergency Health Systems P.O. Box 95026 Lincoln, NE 68509-5026 Phone: (402) 471-0539 E-mail: [email protected] If you have questions or concerns while filling out the PRQ, please contact: State of Nebraska Trauma Nurse Specialist OR your Regional Trauma Program Manager (please reference website list of Designated Trauma Centers on the website cited above for names and contact information). I. PURPOSE: A. The purpose of this questionnaire for Consultation Visits is: 1. To provide your institution with an outline of what site visitors will be discussing with you. -

Mass/Multiple Casualty Triage

9.1 MASS/MULTIPLE CASUALTY TRIAGE PURPOSE · The goal of the mass/multiple Casualty Triage protocol is to prepare for a unified, coordinated, and immediate EMS mutual aid response by prehospital and hospital agencies to effectively expedite the emergency management of the victims of any type of Mass Casualty Incident (MCI). · Successful management of any MCI depends upon the effective cooperation, organization, and planning among health care professionals, hospital administrators and out-of-hospital EMS agencies, state and local government representatives, and individuals and/or organizations associated with disaster-related support agencies. · Adoption of Model Uniform Core Criteria (MUCC). DEFINITIONS Multiple Casualty Situations · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries do not exceed the ability of the provider to render care. Patients with life-threatening injuries are treated first. Mass Casualty Incidents · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries exceed the capability of the provider, and patients sustaining major injuries who have the greatest chance of survival with the least expenditure of time, equipment, supplies, and personnel are managed first. H a z GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS m Initial assessment to include the following: a t · Location of incident. & · Type of incident. M · Any hazards. C · Approximate number of victims. I · Type of assistance required. 9 . 1 COMMUNICATION · Within the scope of a Mass Casualty Incident, the EMS provider may, within the limits of their scope of practice, perform necessary ALS procedures, that under normal circumstances would require a direct physician’s order. · These procedures shall be the minimum necessary to prevent the loss of life or the critical deterioration of a patient’s condition. -

Hendricks Regional Health Emergency Medicine Rules and Regulations

HENDRICKS REGIONAL HEALTH EMERGENCY MEDICINE RULES AND REGULATIONS I. Scope of Service The Emergency Department offers emergency care twenty-four hours a day with at least one physician experienced in emergency care on duty, and specialty consultation is available within approximately sixty minutes. Initial consultation through two-way voice communication is available. The hospital's scope of services includes: A. Providing acute care for the critically ill and traumatically injured B. Caring for patients with acute and chronic illnesses C. Maintaining two way communication with the EMS services D. Follow-up care on selected patients E. Providing EMS direction F. Providing examination rooms for "professional services" (courtesy) patients. The Emergency Department is classified as a Level II Emergency Department. II. Physician Coverage - Qualifications Medical coverage of the Emergency Department shall be available twenty-four (24) hours a day. Original and additional physicians who provide emergency services at the hospital shall be duly licensed to practice medicine in the State of Indiana, shall be a member of the Medical Staff of the hospital, shall have three (3) years residency training in family practice, emergency medicine, internal medicine, and be board eligible or board certified; shall possess ACLS, ATLS, PALS, and Neonatal Resuscitation certification, unless Board Certified in Emergency Medicine; and shall meet and maintain requirements for active membership in the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) or the American Academy of Emergency Medicine (AAEM). With prior consent of the Hospital, temporary physicians may be utilized to staff the Emergency Department and must be duly licensed to practice medicine in the State of Indiana, must be in at least their second post graduate year of residency, and must be ACLS certified. -

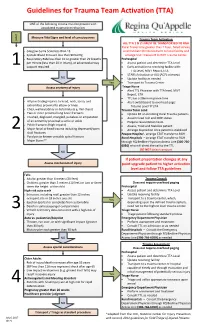

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

Emergency Department Rapid Medical Assessment: Overall Effect and Mechanistic Considerations

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 48, No. 5, pp. 620–627, 2015 Copyright Ó 2015 Elsevier Inc. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.025 Administration of Emergency Medicine EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT RAPID MEDICAL ASSESSMENT: OVERALL EFFECT AND MECHANISTIC CONSIDERATIONS Stephen J. Traub, MD,*† Joseph P. Wood, MD,*† James Kelley, MD,*† David M. Nestler, MD,†‡ Yu-Hui Chang, PHD,§ Soroush Saghafian, PHD,†{ and Christopher A. Lipinski, MD*† *Department of Emergency Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, Ariz, †Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn, ‡Department of Emergency Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn, §Division of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, Ariz, and {School of Computing, Informatics and Decision Systems Engineering, Arizona State University, Tempe, Ariz Reprint Address: Stephen J. Traub, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Mayo Clinic Arizona, 5777 E. Mayo Boulevard, Phoenix, AZ 85054 , Abstract—Background: Although the use of a physician INTRODUCTION and nurse team at triage has been shown to improve emer- gency department (ED) throughput, the mechanism(s) by Improving emergency department (ED) throughput is an which these improvements occur is less clear. Objectives: 1) important area for hospital process improvement. Poor To describe the effect of a Rapid Medical Assessment (RMA) ED throughput has been associated with increased 28- team on ED length of stay (LOS) and rate of left without being day mortality from pneumonia, delays to percutaneous seen (LWBS); 2) To estimate the effect of RMA on different groups of patients. Methods: For Objective 1, we compared coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial LOS and LWBS on dates when we utilized RMA to compara- infarction, adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients ble dates when we did not.