Heart Rate and Posttraumatic Stress in Injured Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measuring Injury Severity

Measuring Injury Severity A brief introduction Thomas Songer, PhD University of Pittsburgh [email protected] Injury severity is an integral component in injury research and injury control. This lecture introduces the concept of injury severity and its use and importance in injury epidemiology. Upon completing the lecture, the reader should be able to: 1. Describe the importance of measuring injury severity for injury control 2. Describe the various measures of injury severity This lecture combines the work of several injury professionals. Much of the material arises from a seminar given by Ellen MacKenzie at the University of Pittsburgh, as well as reference works, such as that by O’Keefe. Further details are available at: “Measuring Injury Severity” by Ellen MacKenzie. Online at: http://www.circl.pitt.edu/home/Multimedia/Seminar2000/Mackenzie/Mackenzie.ht m O’Keefe G, Jurkovich GJ. Measurement of Injury Severity and Co-Morbidity. In Injury Control. Rivara FP, Cummings P, Koepsell TD, Grossman DC, Maier RV (eds). Cambridge University Press, 2001. 1 Degrees of Injury Severity Injury Deaths Hospitalization Emergency Dept. Physician Visit Households Material in the lectures before have spoken of the injury pyramid. It illustrates that injuries of differing levels of severity occur at different numerical frequencies. The most severe injuries occur less frequently. This point raises the issue of how do you compare injury circumstances in populations, particularly when levels of severity may differ between the populations. 2 Police EMS Self-Treat Emergency Dept. doctor Injury Hospital Morgue Trauma Center Rehab Center Robertson, 1992 For this issue, consider that injuries are often identified from several different sources. -

Traumatic Brain Injury

REPORT TO CONGRESS Traumatic Brain Injury In the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation Submitted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention The Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation is a publication of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH Director, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Debra Houry, MD, MPH Director, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Grant Baldwin, PhD, MPH Director, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention The inclusion of individuals, programs, or organizations in this report does not constitute endorsement by the Federal government of the United States or the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Atlanta, GA. Executive Summary . 1 Introduction. 2 Classification . 2 Public Health Impact . 2 TBI Health Effects . 3 Effectiveness of TBI Outcome Measures . 3 Contents Factors Influencing Outcomes . 4 Effectiveness of TBI Rehabilitation . 4 Cognitive Rehabilitation . 5 Physical Rehabilitation . 5 Recommendations . 6 Conclusion . 9 Background . 11 Introduction . 12 Purpose . 12 Method . 13 Section I: Epidemiology and Consequences of TBI in the United States . 15 Definition of TBI . 15 Characteristics of TBI . 16 Injury Severity Classification of TBI . 17 Health and Other Effects of TBI . -

Pre-Review Questionnaire Frequently Asked Questions

Pre-Review Questionnaire (PRQ) Frequently Asked Questions 1. Can abbreviations be used on the Pre-Review Questionnaire? Do not use abbreviations on the Pre-Review Questionnaire because abbreviations may not be the same from trauma care facility to trauma care facility. Write out all words and examples. 2. For the type of visit (question # 1 on the Pre-Review Questionnaire and Application Checklist form, DPH 7484), do I mark first visit or renewal visit? Mark the first visit this time. This is the first site visit made by the State of Wisconsin to your trauma care facility. The site visit means the actual physical site visit to your hospital. Filling out the assessment criteria document does not count as a site visit. The renewal box will be marked on your second site visit which will not start until at least 2010. This document is made so that the state does not have to create another Pre- Review Questionnaire document for future site visits. The renewal box can be checked and new information added or updated. 3. What are injury prevention initiatives and/or programs? Injuries cause death and disability. Strategies that decrease or prevent injury can improve the health of the community. Injury prevention initiatives and/or strategies focus primarily on environmental design, product design, human behavior, education, and legislative and regulatory requirements that support environmental and behavioral change (Center for Disease Control). Examples can include, but are not limited to: car seat clinics, bike helmet clinics, burn safety camp, farm safety, teen alcohol prevention programs (ENCARE, PARTY, Every 15 Minutes, etc…), ATV safety, hunting safety, snowmobiling safety, boating safety, poison control prevention, seat belt safety, etc… There are so many great national, state, and/or local programs to utilize or you can develop your own. -

Mass/Multiple Casualty Triage

9.1 MASS/MULTIPLE CASUALTY TRIAGE PURPOSE · The goal of the mass/multiple Casualty Triage protocol is to prepare for a unified, coordinated, and immediate EMS mutual aid response by prehospital and hospital agencies to effectively expedite the emergency management of the victims of any type of Mass Casualty Incident (MCI). · Successful management of any MCI depends upon the effective cooperation, organization, and planning among health care professionals, hospital administrators and out-of-hospital EMS agencies, state and local government representatives, and individuals and/or organizations associated with disaster-related support agencies. · Adoption of Model Uniform Core Criteria (MUCC). DEFINITIONS Multiple Casualty Situations · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries do not exceed the ability of the provider to render care. Patients with life-threatening injuries are treated first. Mass Casualty Incidents · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries exceed the capability of the provider, and patients sustaining major injuries who have the greatest chance of survival with the least expenditure of time, equipment, supplies, and personnel are managed first. H a z GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS m Initial assessment to include the following: a t · Location of incident. & · Type of incident. M · Any hazards. C · Approximate number of victims. I · Type of assistance required. 9 . 1 COMMUNICATION · Within the scope of a Mass Casualty Incident, the EMS provider may, within the limits of their scope of practice, perform necessary ALS procedures, that under normal circumstances would require a direct physician’s order. · These procedures shall be the minimum necessary to prevent the loss of life or the critical deterioration of a patient’s condition. -

Abbreviated Injury Scale 1985 Revision

ABBREVIATED INJURY SCALE 1985 REVISION DICTIONARY EXTERNAL ABBREVIATED INJURY SCALE HEAD&FACE 1985 REVISION COMMITTEE ON INJURY SCALING NECK Thomas A.Gennarelli. Philadelphia PA (Chairman) Susan P. Baker. Baltimore MD THORAX Robert W. Bryant. Bloomfield Hills MI H.A. Fenner. Hobbs NM Robert N. Green. London ONT CONTENTS A.C. Hering. Chicago IL ABDOMEN & PELVIC Donald F. Huelke. Ann Arbor MI Ellen J. Mackenzie. Baltimore MD Elaine Petrucelli. Arlington Heights IL John E. Pless. Indianapolis IN John D. States. Rochester NY SPINE Donald D. Trunkey. San Francisco CA EXTREMITIES & BONY ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Members of the American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma were consulted to assist in reviewing the sections on the thorax and abdomen and in developing the new injury descriptions for the vascular system. The American Association for Automotive Medicine is grateful to present and former members of the COT’s ad hoc committee on injury scaling for their contributions to this edition of the AIS, especially to the following physicians: William F. Blaisdell. M.D.: Charles F. Frey M.D.: Frank R. Lewis. Jr. M.D. and Donald F. Trunkey. M.D. Copyright 1985 American Association for Automotive Medicine Arlington Heights II 60005, USA TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION The Abbreviated Injury Scale: A Historical Note 1 Assessment of Multiple Injuries 1 Fundamental Improvements to AIS 85 3 Future Directions 4 References 5 INJURY SCALING DICTIONARY Format 7 Changes in AIS Code Numbers 8 Terminology 8 Other Clarifications 8 Condensed AIS 85 9 Dictionary Index 10 AIS Severity Code 17 INJURY DESCRIPTIONS External 18 Skin 18 Burns 19 Head 21 Cranium and Brain 24 Face including ear and eye 28 (Continued on reverse) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Neck 31 Thorax 35 Abdomen and Pelvic Contents 44 Spine Cervical spine 55 Thoracic Spine 57 Lumbar spine 59 Extremities and Bony Pelvis Upper Extremity 61 Lower Extremity 66 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ABBREVIATED INJURY SCALE A HISTORICAL NOTE Classification of road transport injuries by types and severity is fundamental to the study of their etiology. -

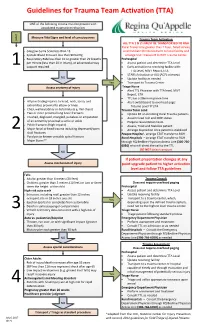

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

Underestimated Traumatic Brain Injury in Multiple Injured Patients; Is the Glasgow Coma Scale a Reliable Tool?

Research Artice iMedPub Journals Trauma & Acute Care 2017 http://www.imedpub.com/ Vol.2 No.2:42 Underestimated Traumatic Brain Injury in Multiple Injured Patients; Is the Glasgow Coma Scale a Reliable Tool? Ladislav Mica1*, Kai Oliver Jensen1, Catharina Keller2, Stefan H. Wirth3, Hanspeter Simmen1 and Kai Sprengel1 1Division of Trauma Surgery, University Hospital of Zürich, 8091 Zürich, Switzerland 2LVR-Klinik, 51109 Köln, Germany 3Orthopädische Universitätsklink Balgrist, 8008 Zürich, Switzerland *Corresponding author: Ladislav Mica, Division of Trauma Surgery, University Hospital of Zürich, 8091 Zürich, Switzerland, Tel: +41 44 255 41 98; E- mail: [email protected] Received date: March 16, 2017; Accepted date: April 12, 2017; Published date: April 20, 2017 Citation: Mica L, Jensen KO, Keller C, Wirth SH, Simmen H, et al. (2017) Underestimated Traumatic Brain Injury in Multiple Injured Patients, is the Glasgow Coma Scale a Reliable Tool? Trauma Acute Care 2: 42. Copyright: © 2017 Mica L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abbreviations: Abstract AIS: Abbreviated Injury Severity Score; ANOVA: Analysis of Variance; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Background: Traumatic brain injuries are common in Evaluation; ATLS: Advanced Trauma Life Support; AUC: Area multiple injured patients. Here, the impact of traumatic under the Curve; CT: Computed Tomography; GCS: Glasgow brain injuries according age and mortality and predictive Coma Scale; IBM: International Business Machines Corporation; value was investigated. ISS: Injury Severity Score; NISS: New Injury Severity Score; ROC: Methods: Totally 2952 patients were included into this Receiver Operating Curve; SAPS: Simplified Acute Physiology sample. -

Injury Severity Scoring

INJURY SEVERITY SCORING Injury Severity Scoring is a process by which complex and variable patient data is reduced to a single number. This value is intended to accurately represent the patient's degree of critical illness. In truth, achieving this degree of accuracy is unrealistic and information is always lost in the process of such scoring. As a result, despite a myriad of scoring systems having been proposed, all such scores have both advantages and disadvantages. Part of the reason for such inaccuracy is the inherent anatomic and physiologic differences that exist between patients. As a result, in order to accurately estimate patient outcome, we need to be able to accurately quantify the patient's anatomic injury, physiologic injury, and any pre-existing medical problems which negatively impact on the patient's physiologic reserve and ability to respond to the stress of the injuries sustained. Outcome = Anatomic Injury + Physiologic Injury + Patient Reserve GLASGOW COMA SCORE The Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) is scored between 3 and 15, 3 being the worst, and 15 the best. It is composed of three parameters : Best Eye Response, Best Verbal Response, Best Motor Response, as given below: Best Eye Response (4) Best Verbal Response (5) Best Motor Response (6) 1. No eye opening 1. No verbal response 1. No motor response 2. Eye opening to pain 2. Incomprehensible sounds 2. Extension to pain 3. Eye opening to verbal 3. Inappropriate words 3. Flexion to pain command 4. Confused 4. Withdrawal from pain 4. Eyes open spontaneously 5. Orientated 5. Localising pain 6. Obeys Commands Note that the phrase 'GCS of 11' is essentially meaningless, and it is important to break the figure down into its components, such as E3 V3 M5 = GCS 11. -

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Minor Trauma – a Prospective Cohort Study T

Medical Hypotheses 135 (2020) 109465 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Medical Hypotheses journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mehy Posttraumatic stress disorder after minor trauma – A prospective cohort study T Katharina Angerpointnera, Stefanie Weberb, Karen Tschechb, Hannah Schubertb, Tanja Herbsta, ⁎ Antonio Ernstbergera, Maximilian Kerschbauma, a Department of Trauma Surgery, University Hospital Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany b AARU Audi Accident Research Unit, University Hospital Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can arise as a reaction to a traumatic experience. While many Posttraumatic stress disorder data concerning PTSD in severely injured patients are available, little is known about this disease in slightly PTSD injured patients after road traffic accidents. It is rather assumed that PTSD does not exist after objectively slight Anxiety disorder injuries. Minor trauma Methods: In total, 36 patients (Injury Severity Score < 16) after road traffic accidents were included in this Road traffic accident prospective cohort study. Next to demographic and accident-specific data, the PDI (Peritraumatic Distress Inventory: individual experienced distress directly during or immediately after the traumatic event), THQ (Trauma History Questionnaire) and the BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory-II: self-report measurement tool to examine the severity of depression) were assessed immediately after trauma (t0). Six weeks (t1) and 3 months (t2) after trauma the Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R), a screening instrument for PTSD, and the BDI-II were collected. Results: Overall 2 patients showed critical measurement values in IES-R after 6 weeks. A strong correlation between PDI and IES-R at t1 and t2 could be detected (p < 0.05). -

A Uniform Triage Scale in Emergency Medicine Information Paper

A Uniform Triage Scale in Emergency Medicine Information Paper Triage: sorting, sifting (Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary) from the French verb trier- “to sort.” Triage has long been considered a simple frontline sorting mechanism in hospital-based emergency departments (EDs). However, evolution in the practice of emergency medicine during the past two decades necessitates a change in how this entry point process is performed and utilized. Many triage systems are in use in the US, but there is no uniform triage scale that would facilitate the development of operational standards in EDs. A nationally standardized triage scale would provide an analytic basis for determining whether the health care system provides safe access to emergency care based on design, resources, and utilization. The performance of EDs could be compared based on case mix and acuity, and expected standards for facilities could be defined. Planners and policy makers would have the tools and the data needed to make rational improvements in the health care delivery system. This paper on triage will acquaint the reader with the history of triage, and provide an overview of the Australian and Canadian systems which are already in use on a national level. The reliability of triage is addressed, and the Canadian and Australian scales are compared. Future implications for a national triage scale are described, along with the goals and benefits of triage development. While there is some controversy about potential liability issues, the many advantages of a national triage scale appear to outweigh any potential disadvantages. History of triage The first medical application of triage occurred on the French battlefield where sorting the victims determined who would be left behind. -

Original Article Article Original LONG-TERM OUTCOMES AFTER UPPER LIMB ARTERIAL INJURIES

14846 August/97 CJS /Page 265 Original Article Article original LONG -TERM OUTCOMES AFTER UPPER LIMB ARTERIAL INJURIES Corry K. van der Sluis, MD;† Daryl S. Kucey, MD, MSc, MPH;* Frederick D. Brenneman, MD;* Gordon A. Hunter, MB BS;* Robert Maggisano MD, FACS;* Henk J. ten Duis, MD, PhD† OBJECTIVE : To assess long-term outcomes in multisystem trauma victims who have arterial injuries to up - per limbs. DESIGN : A retrospective case series. SETTING : Tertiary care regional trauma centre in a university hospital. PATIENTS : All consecutive severely injured patients (Injury Severity Score greater than 15) with an upper limb arterial injury treated between January 1986 and January 1995. Demographic data and the nature and management of the arterial and associated injuries were determined from the trauma registry and the hospital records. OUTCOME MEASURES : Death rate, discharge disposition, residual disabilities and functional outcomes as measured by the Glasgow Outcome Scale. RESULTS : Twenty-five (0.6%) of 4538 trauma patients assessed during the study period suffered upper ex - tremity arterial injuries. Nineteen of them were victims of blunt trauma. The death rate was 24%. There were 10 primary and no secondary amputations. An autogenous vein interposition graft was placed in 10 patients. Concomitant fractures or nerve injuries in the upper limb were present in 80% and 86% of the pa - tients, respectively. Long-term follow-up data (mean 2 years) were obtained in 16 of the 19 who survived to hospital discharge. The residual disability rate was high. It included upper limb joint contractures, pain and persistent neural deficits (69%). Associated injuries in other body areas also contributed to overall dis - ability.