Queering Heteronormativity at Home in London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transgender Representation on American Narrative Television from 2004-2014

TRANSJACKING TELEVISION: TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION ON AMERICAN NARRATIVE TELEVISION FROM 2004-2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Kelly K. Ryan May 2021 Examining Committee Members: Jan Fernback, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Ron Becker, External Member, Miami University ABSTRACT This study considers the case of representation of transgender people and issues on American fictional television from 2004 to 2014, a period which represents a steady surge in transgender television characters relative to what came before, and prefigures a more recent burgeoning of transgender characters since 2014. The study thus positions the period of analysis as an historical period in the changing representation of transgender characters. A discourse analysis is employed that not only assesses the way that transgender characters have been represented, but contextualizes American fictional television depictions of transgender people within the broader sociopolitical landscape in which those depictions have emerged and which they likely inform. Television representations and the social milieu in which they are situated are considered as parallel, mutually informing discourses, including the ways in which those representations have been engaged discursively through reviews, news coverage and, in some cases, blogs. ii To Desmond, Oonagh and Eamonn For everything. And to my mother, Elaine Keisling, Who would have read the whole thing. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the research and writing of this dissertation, I have received a great deal of support and assistance, and therefore offer many thanks. To my Dissertation Chair, Jan Fernback, whose feedback on my writing and continued support and encouragement were invaluable to the completion of this project. -

Montréal's Gay Village

Produced By: Montréal’s Gay Village Welcoming and Increasing LGBT Visitors March, 2016 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ÉTUDE SUR LE VILLAGE GAI DE MONTRÉAL Partenariat entre la SDC du Village, la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec › La Société de développement commercial du Village et ses fiers partenaires financiers, que sont la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec, sont heureux de présenter cette étude réalisée par la firme Community Marketing & Insights. › Ce rapport présente les résultats d’un sondage réalisé auprès de la communauté LGBT du nord‐est des États‐ Unis (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, État de New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvanie, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginie, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois), du Canada (Ontario et Colombie‐Britannique) et de l’Europe francophone (France, Belgique, Suisse). Il dresse un portrait des intérêts des touristes LGBT et de leurs appréciations et perceptions du Village gai de Montréal. › La première section fait ressortir certaines constatations clés alors que la suite présente les données recueillies et offre une analyse plus en détail. Entre autres, l’appréciation des touristes qui ont visité Montréal et la perception de ceux qui n’en n’ont pas eu l’occasion. › L’objectif de ce sondage est de mieux outiller la SDC du Village dans ses démarches de promotion auprès des touristes LGBT. 2 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ABOUT CMI OVER 20 YEARS OF LGBT INSIGHTS › Community Marketing & Insights (CMI) has been conducting LGBT consumer research for over 20 years. Our practice includes online surveys, in‐depth interviews, intercepts, focus groups (on‐site and online), and advisory boards in North America and Europe. -

Curating Precarity. Swedish Queer Film Festivals As Micro-Activism

Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis Uppsala Studies in Media and Communication 16 Curating Precarity Swedish Queer Film Festivals as Micro-Activism SIDDHARTH CHADHA Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lecture Hall 2, Ekonomikum, Kyrkogårdsgatan 10, Uppsala, Thursday, 15 April 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Dr. Marijke de Valck (Department of Media and Culture, Utrecht University). Abstract Chadha, S. 2021. Curating Precarity. Swedish Queer Film Festivals as Micro-Activism. Uppsala Studies in Media and Communication 16. 189 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-1145-6. This research is based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted at Malmö Queer Film Festival and Cinema Queer Film Festival in Stockholm, between 2017-2019. It explores the relevance of queer film festivals in the lives of LGBTQIA+ persons living in Sweden, and reveals that these festivals are not simply cultural events where films about gender and sexuality are screened, but places through which the political lives of LGBTQIA+ persons become intelligible. The queer film festivals perform highly contextualized and diverse sets of practices to shape the LGBTQIA+ discourse in their particular settings. This thesis focuses on salient features of this engagement: how the queer film festivals define and articulate “queer”, their engagement with space to curate “queerness”, the role of failure and contingency in shaping the queer film festivals as sites of democratic contestations, the performance of inclusivity in the queer film festival organization, and the significance of these events in the lives of the people who work or volunteer at these festivals. -

Mcsporran, Cathy (2007) Letting the Winter In: Myth Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction

McSporran, Cathy (2007) Letting the winter in: myth revision and the winter solstice in fantasy fiction. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5812/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Letting the Winter In: Myth Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction Cathy McSporran Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature, University of Glasgow Submitted October 2007 @ Cathy McSporran 2007 Abstract Letting the Winter In: Myth-Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction This is a Creative Writing thesis, which incorporates both critical writing and my own novel, Cold City. The thesis explores 'myth-revision' in selected works of Fantasy fiction. Myth- revision is defined as the retelling of traditional legends, folk-tales and other familiar stories in such as way as to change the story's implied ideology. (For example, Angela Carter's 'The Company of Wolves' revises 'Red Riding Hood' into a feminist tale of female sexuality and empowerment.) Myth-revision, the thesis argues, has become a significant trend in Fantasy fiction in the last three decades, and is notable in the works of Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman and Philip Pullman. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Carrying Queerness Queerness, Performance

DOCTORAL THESIS Carrying Queerness Queerness, Performance and the Archive Hunt, Raymond Justin Award date: 2013 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Carrying Queerness: Queerness, Performance and the Archive by Raymond Justin Hunt, BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Drama, Theatre and Performance University of Roehampton 2013 ABSTRACT This dissertation responds to the archival turn in critical theory by examining a relation between queerness, performance and the archive. In it I explore institutional archives and the metaphors of the archive as it operates in the academy, while focusing particularly on the way in which queerness may come to be archived. Throughout I use the analytic of performance. This work builds on and extends from crucial work in Queer studies, Performance Studies and Archival Studies. -

Not Just Words: Exposure to Homophobic Epithets Leads To

EJSP RESEARCH ARTICLE Not “just words”: Exposure to homophobic epithets leads to dehumanizing and physical distancing from gay men Fabio Fasoli*, Maria Paola Paladino†,AndreaCarnaghi‡, Jolanda Jetten§, Brock Bastian¶ & Paul G. Bain§,# * Centro de Investigação e Intervenção Social, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal † Department of Psychology and Cognitive Science, University of Trento, Rovereto, Italy ‡ Department of Life Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy § School of Psychology, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Brisbane, Australia ¶ School of Psychology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia # School of Psychology and Counselling, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia Correspondence Abstract Fabio Fasoli, ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Centro de Investigação e Intervenção We examined whether homophobic epithets (e.g., faggot) function as labels of Social, Lisbon, Portugal. deviance for homosexuals that contribute to their dehumanization and phys- E-mail: [email protected]; ical distance. Across two studies, participants were supraliminally (Study 1) [email protected] and subliminally (Study 2) exposed to a homophobic epithet, a category label, or a generic insult. Participants were then asked to associate human- Received: 9 June 2014 related and animal-related words to homosexuals and heterosexuals. Results Accepted: 1 August 2015 showed that after exposure to a homophobic epithet, compared with a cate- gory label or a generic insult, participants associated less human-related http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2148 words with homosexuals, indicating dehumanization. In Study 2, we also Keywords: derogatory labels, deviance, assessed the effect of a homophobic epithet on physical distance from a target dehumanization, homophobia, physical group member and found that homophobic epithets led to greater physical distance distancing of a gay man. -

WGSS 392Q Introduction to Queer Theory Spring 2017

1 WGSS 392Q Introduction to Queer Theory Spring 2017 Tuesday & Thursday, 1:00-2:15 PM Class room: South College W101 Dr. J. Jeanine Ruhsam [email protected] Office Hours: T-TR. 10:00-11:15 AM Office: South College W421 Course Description Queer Theory critically examines the way power works to institutionalize and legitimate certain forms and expressions of sexuality and gender while stigmatizing others. Queer Theory followed the emergence and popularity of Gay and Lesbian (now, LGBT or Queer) Studies in the academy. Whereas LGBT Studies seeks to analyze LGBT people as stable identities, Queer Theory problematizes and challenges rigid identity categories, norms of sexuality and gender and the oppression and violence that such hegemonic norms justify. Often considered the "deconstruction" of LGBT studies, Queer Theory destabilizes sexual and gender identities allowing and encouraging multiple, unfettered interpretations of cultural phenomena. It predicates that all sexual behaviors and gender expressions, all concepts linking such to prescribed, associated identities, and their categorization into “normal” or “deviant” sexualities or gender, are constructed socially and generate modes of social meaning. Queer theory follows and expands upon feminist theory by refusing the belief that sexuality and gender identity are essentialist categories determined by biology that can thus be empirically judged by fixed standards of morality and “truth.” We will begin the course by developing a critical understanding of Queer Theory through reading foundational texts by Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, Eve Sedgwick, Gayle Rubin and Leo Bersani. We will then examine the relationships between Queer Theory and other social and cultural theories that probe and critique power, privilege, and normativity, including critical race theory, transgender studies, feminist theory, and disability studies. -

An Unreconstructed Ode to Eve Sedgwick (And Others) Brenda Cossman

Queering Queer Legal Studies: An Unreconstructed Ode to Eve Sedgwick (and Others) Brenda Cossman Abstract The essay explores the extant field queer legal studies and maps the multiple meanings of “queer” deployed within it. I distinguish queer from LGBT, but resist any further disciplining of the term. I propose instead an understanding of queer legal studies as a sensibility. Neither a prescription nor a pronouncement, the article is written as an ode to Eve Sedgewick, her axioms and her reparative readings. I offer the essay as a celebration of queer legal studies to date and of its hopeful potentialities into an unknown future. I. Axiom 1: Queer legal theory exists. There is a body of queer legal studies. It is not part of a fantastical yet to be realized future. It is found in the oft-cited works of Francisco Valdes,1 Carl Stychin,2 Kendall Thomas,3 and Janet Halley.4 But, there is so much more. And it exists independently of what might be called LGBT legal studies. I begin with the assertion that queer legal theory exists because many who write queer legal theory begin with a counter-assertion—that there is little or no queer legal scholarship.5 The claim is puzzling. My discomfort with the claim is perhaps based in unrequited love, as I would locate my own work for the last two decades within the tradition of queer legal studies. Professor of Law, University of Toronto. I am indebted to Joseph Fischel for his generous and razor sharp engagement with this essay. 1 Francisco Valdes, Queers, Sissies, Dykes, and Tomboys: Deconstructing the Conflation of “Sex,” “Gender,” and “Sexual Orientation” in Euro-American Law and Society, 83 Cal. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, MAQUAT 10, 08/08/2008

UNiTED ST.c~S ENVIRONMENTA.L'PROTECTI9NAGC1V [o3J-Cf -63' ~/g-'fcH;oe Ms. Elizabeth Tannehill Mason Chemical Company .r~~---~ .. 721 W. Algonquin Road ",'". 'I' ~1 , ,r: Arlington Heights, IL 60005 AUG 8 200a Subject: Maquat 10 EPA Registration No.: 10324-63 Amendment Date: March 19,2008 EP A Receipt Date: March 28, 2008 Dear Ms. Tannehill, The following amendment, submitted in connection With registration under section 3(c)(7)(A) of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and.Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), as amended, is 'acceptable subject to the conditions listed below: • Addition of public health organisms • Addition of directions for use and marketing claims • ,Acceptable Data Correct your data matrix to indicate the correct MRIDs: Porcine Rotavinis: 45171410 and Porcine Respiratory and Reproductive Syndrome: 45171409. Community Associated Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Submitted study,.MRID473868-01 Acceptable, 625 ppm active in 5% . soil for 10 minutes Avian Influenza A (H5Nl) virus Submitted study, MRID 473868-02 Acceptable, 625 ppm active in 5% soil for 10 minutes Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 Submitted study, MRID 47386g~03 Acceptable, 625 ppm active in 5% soil for 2 minutes cONcuRReNces.' " . .. SYMBOL ••• J§l~.e ...................... _.~ ................ .. 0.............. ·o ••• _~ ......~....... .. .~O... ...• ....... .. .... 00"' ......... 0... ..0 .• 00." ...... SURNAME" -.;. ~ . DA1"E .; ••• ~J;j6~ .......... ~ ........... ~ .............. •••••••••••••••• ~~ •.•••• ~.......... ••••••••••••••••• • .............. _ ••••• ~ •••••• o ••••• ...... OFfiCIAL fiLE COpy EPA Form 1320-1A (1190) P,illud 011 Re~/ed Pa~ UNITED ST[~S ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECT'ION AGC~CY Conditions Revise the label as follows: 1) Delete the following organism from the "Food Contact SanitiZing Performance" section on pages three and twelve: Clostridium perfringens-vegetative. The Agency is not longer accepting claims of effectiveness against the vegetative form of this organism. -

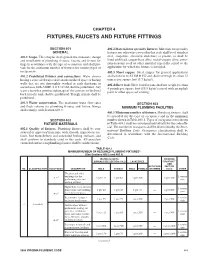

Chapter 4 Fixtures, Faucets and Fixture Fittings

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen CHAPTER 4 FIXTURES, FAUCETS AND FIXTURE FITTINGS SECTION 401 402.2 Materials for specialty fixtures. Materials for specialty GENERAL fixtures not otherwise covered in this code shall be of stainless 401.1 Scope. This chapter shall govern the materials, design steel, soapstone, chemical stoneware or plastic, or shall be and installation of plumbing fixtures, faucets and fixture fit- lined with lead, copper-base alloy, nickel-copper alloy, corro- tings in accordance with the type of occupancy, and shall pro- sion-resistant steel or other material especially suited to the vide for the minimum number of fixtures for various types of application for which the fixture is intended. occupancies. 402.3 Sheet copper. Sheet copper for general applications 401.2 Prohibited fixtures and connections. Water closets shall conform to ASTM B 152 and shall not weigh less than 12 having a concealed trap seal or an unventilated space or having ounces per square foot (3.7 kg/m2). walls that are not thoroughly washed at each discharge in 402.4 Sheet lead. Sheet lead for pans shall not weigh less than accordance with ASME A112.19.2M shall be prohibited. Any 4 pounds per square foot (19.5 kg/m2) coated with an asphalt water closet that permits siphonage of the contents of the bowl paint or other approved coating. back into the tank shall be prohibited. Trough urinals shall be prohibited. 401.3 Water conservation. The maximum water flow rates SECTION 403 and flush volume for plumbing fixtures and fixture fittings MINIMUM PLUMBING FACILITIES shall comply with Section 604.4. -

2 the Robo-Toilet Revolution the Actress and the Gorilla

George, Rose, 2014, The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters (pp. 39-64). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition. 2 THE ROBO-TOILET REVOLUTION THE ACTRESS AND THE GORILLA The flush toilet is a curious object. It is the default method of excreta disposal in most of the industrialized, technologically advanced world. It was invented either five hundred or two thousand years ago, depending on opinion. Yet in its essential workings, this everyday banal object hasn’t changed much since Sir John Harington, godson of Queen Elizabeth I, thought his godmother might like something that flushed away her excreta, and devised the Ajax, a play on the Elizabethan word jakes, meaning privy. The greatest improvements to date were made in England in the later years of the eighteenth century and the early years of the next by the trio of Alexander Cumming (who invented a valve mechanism), Joseph Bramah (a Yorkshireman who improved on Cumming’s valve and made the best lavatories to be had for the next century), and Thomas Crapper (another Yorkshireman who did not invent the toilet but improved its parts). In engineering terms, the best invention was the siphonic flush, which pulls the water out of the bowl and into the pipe. For the user, the S-bend was the godsend, because the water that rested in the bend created a seal that prevented odor from emerging from the pipe. At the height of Victorian invention, when toilets were their most ornate and decorated with the prettiest pottery, patents for siphonic flushes, for example, were being requested at the rate of two dozen or so a year. -

It's a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Spring 2011 It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood Cori E. Walter Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies Commons Recommended Citation Walter, Cori E., "It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood" (2011). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 6. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/6 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Cori E. Walter May, 2011 Mentor: Dr. Claire Strom Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida 2 Table of Contents________________________________________________________ Introduction Part One: The History of the Gayborhood The Gay Ghetto, 1890 – 1900s The Gay Village, 1910s – 1930s Gay Community and Districts Go Underground, 1940s – 1950s The Gay Neighborhood, 1960s – 1980s Conclusion Part Two: A Short History of the City Urban Revitalization and Gentrification Part Three: Orlando’s Gay History Introduction to Thornton Park, The New Gayborhood Thornton Park, Pre-Revitalization Thornton Park, The Transition The Effects of Revitalization Conclusion 3 Introduction_____________________________________________________________ Mister Rogers' Neighborhood is the longest running children's program on PBS.