Agropoetics-Reader.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mississippi River Find

The Journal of Diving History, Volume 23, Issue 1 (Number 82), 2015 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 04/10/2021 06:15:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32902 First Quarter 2015 • Volume 23 • Number 82 • 23 Quarter 2015 • Volume First Diving History The Journal of The Mississippi River Find Find River Mississippi The The Journal of Diving History First Quarter 2015, Volume 23, Number 82 THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER FIND This issue is dedicated to the memory of HDS Advisory Board member Lotte Hass 1928 - 2015 HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA A PUBLIC BENEFIT NONPROFIT CORPORATION PO BOX 2837, SANTA MARIA, CA 93457 USA TEL. 805-934-1660 FAX 805-934-3855 e-mail: [email protected] or on the web at www.hds.org PATRONS OF THE SOCIETY HDS USA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Ernie Brooks II Carl Roessler Dan Orr, Chairman James Forte, Director Leslie Leaney Lee Selisky Sid Macken, President Janice Raber, Director Bev Morgan Greg Platt, Treasurer Ryan Spence, Director Steve Struble, Secretary Ed Uditis, Director ADVISORY BOARD Dan Vasey, Director Bob Barth Jack Lavanchy Dr. George Bass Clement Lee Tim Beaver Dick Long WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONTINUED Dr. Peter B. Bennett Krov Menuhin SUPPORT OF THE FOLLOWING: Dick Bonin Daniel Mercier FOUNDING CORPORATIONS Ernest H. Brooks II Joseph MacInnis, M.D. Texas, Inc. Jim Caldwell J. Thomas Millington, M.D. Best Publishing Mid Atlantic Dive & Swim Svcs James Cameron Bev Morgan DESCO Midwest Scuba Jean-Michel Cousteau Phil Newsum Kirby Morgan Diving Systems NJScuba.net David Doubilet Phil Nuytten Dr. -

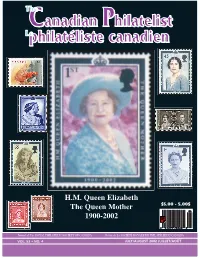

TCP July/Aug Pages

The CCanadiananadian PPhilatelisthilatelist Lephilatphilatéélisteliste canadiencanadien H.M. Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother $5.00 - 5,00$ 1900-2002 Journal of The ROYAL PHILATELIC SOCIETY OF CANADA Revue de La SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE DE PHILATÉLIE DU CANADA VOL. 53 • NO. 4 JULY/AUGUST 2002 JUILLET/AOÛT Le philatéliste canadien/TheCanadianPhilatelist Juillet -Août2002/171 Go with the proven leader CHARLES G. FIRBY AUCTIONS 1• 248•666•5333 TheThe CCanadiananadian PPhilatelisthilatelist LeLephilatphilatéélisteliste canadiencanadien Journal of The ROYAL PHILATELIC Revue de La SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE DE SOCIETY OF CANADA PHILATÉLIE DU CANADA Volume 53, No. 4 Number / Numéro 311 July - August 2002 Juillet – Août FEATURE ARTICLES / ARTICLES DE FOND ▲ The Queen Mum, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother by George Pepall 174 Double Print Errors on Canadian Stamps by Joseph Monteiro 177 The Sea Floor Post Office by Ken Lewis 182 The Date of Issue of the Two-Cent Registered Letter Stamp by George B. Arfken and Horace W. Harrison 184 The Early History of Envelopes by Dale Speirs 185 ▲ Blueberries and Mail by Sea by Captain Thomas Killam 188 The Surprises of Philately by Kimber A. Wald 190 ▲ Canada’s 1937 George VI Issue by J.J. Edward 193 Jamaican Jottings by “Busha” 197 The Short Story Column by “Raconteur” 200 Guidelines for Judging Youth Exhibits Directives pour Juger les Collections Jeunesse 202 Early German Cancels by “Napoleon” 207 In Memoriam – Harold Beaupre 209 172 / July - August 2002 The Canadian Philatelist / Le philatéliste canadien THE ROYAL PHILATELIC DEPARTMENTS / SERVICES SOCIETY OF CANADA LA SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE DE President’s Page / La page du président 211 PHILATÉLIE DU CANADA Patron Her Excellency The Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson Letters / Lettres 214 C.C., C.M.M., C.D., Governor General of Canada Président d’honneur Son Excellence le très honorable Coming Events / Calendrier 215 Adrienne Clarkson. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Temas Sociales 38.Pdf

TEMAS SOCIALES Nº 38 René Pereira Morató DIRECTOR IDIS AUTORES Luis Alemán Marcelo Jiménez Javier Velasco Carlos Ichuta Eduardo Paz Héctor Luna Antonio Moreno Alisson Spedding Gumercindo Flores La Paz - Bolivia 2016 FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS TEMAS SOCIALES Nº 38 René Pereira Morató DIRECTOR IDIS AUTORES Luis Alemán Marcelo Jiménez Javier Velasco Carlos Ichuta Eduardo Paz Héctor Luna Antonio Moreno Alison Spedding Gumercindo Flores CARRERA DE SOCIOLOGÍA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIOLÓGICAS - IDIS “MAURICIO LEFEBVRE” TEMAS SOCIALES Nº 38 – Mayo 2016 UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES CARRERA DE SOCIOLOGÍA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIOLÓGICAS - IDIS “MAURICIO LEFEBVRE” Av. Villazón Nº 1995. 2º Piso, Edificio René Zavaleta Mercado Teléfono: 2440388 E-mail: [email protected] La Paz - Bolivia Director de la Carrera de Sociología: Lic. Fidel Rojas Álvarez Director del IDIS: M.Sc. René Pereira Morató Responsable de la Edición: Freddy R. Vargas M. Diseño y diagramación: Antonio Ruiz Impresión: III-CAB Artista invitado: Enrique Arnal (1932-2016). Nació en Catavi, Potosí. Hizo varias exposiciones individuales en La Paz, Buenos Aires, Asunción, Santiago de Chile, Washington, Bogotá, Lima, París y Nueva York. En 2007 recibió el Premio Municipal “A la obra de una vida” del Salón Pedro Domingo Murillo de La Paz. Imagen de Portada: Toro (acrílico sobre lienzo). COMITÉ EDITORIAL Silvia de Alarcón Chumacero Instituto Internacional de Integración Convenio Andrés Bello (Bolivia) Raúl España -

Thinking Art Thinking

CRMEP Books – Thinking art – cover 232 pp. Trim size 216 x 138 mm – Spine 18 mm 4-colour, matt laminate Caroline Bassett Dave Beech art Thinking Ayesha Hameed Klara Kemp-Welch Jaleh Mansoor Christian Nyampeta Peter Osborne Ludger Schwarte Keston Sutherland Giovanna Zapperi Thinking art materialisms, labours, forms isbn 978-1-9993337-4-4 edited by CRMEP BOOKS PETER OSBORNE 9 781999 333744 Thinking art Thinking art materialisms, labours, forms edited by PETER OSBORNE Published in 2020 by CRMEP Books Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy Penrhyn Road campus, Kingston University, Kingston upon Thames, kt1 2ee, London, UK www.kingston.ac.uk/crmep isbn 978-1-9993337-4-4 (pbk) isbn 978-1-9993337-5-1 (ebook) The electronic version of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC-BYNC-ND). For more information, please visit creativecommons.org. The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Designed and typeset in Calluna by illuminati, Grosmont Cover design by Lucy Morton at illuminati Printed by Short Run Press Ltd (Exeter) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Contents Preface PETER OSBORNE ix MATERIALISMS 1 Digital materialism: six-handed, machine-assisted, furious CAROLINE bASSETT 3 2 The consolation of new materialism KESTOn sUtHeRLAnD 29 ART & LABOUR 3 Art’s anti-capitalist ontology: on the historical roots of the -

World Bank Document

ORGANISATION POUR LA MISE EN VALEUR DU FLEUVE SENEGAL HAUT- COMMISSAIRIAT ETUDE D'IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL (EIE), Public Disclosure Authorized CADRE DE POLITIQUE DE REINSTALLATION DES POPULATIONS (CPRP), PLAN DE GESTION DES PESTES ET PESTICIDES (PGPP) POUR LES DIFFERENTES ACTIVITES DU PROJET CADRE REGIONAL STRATEGIQUE DE GESTION ENVIRONNEMENTALE ET SOCIALE Public Disclosure Authorized PROGRAMME DE GESTION INTEGREE DES RESSOURCES EN EAU ET DE DEVELOPPEMENT DES USAGES A BUTS MULTIPLES DANS LE BASSIN DU FLEUVE SENEGAL El 312 Financement: Banque Mondiale VOL. 2 Public Disclosure Authorized Rapport principal Version Définitive Janvier 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized STLDL ~SAPC LO I N T E R N A T I O N A L TUNIS - TUNISIE DAKAR - SENEGAL BAMAKO - MALI Programme de Gestion Intégréedes Ressourcesen Eau et de Développementdes Usagesà Buts Multiplesdans le Bassindu Fleuve Sénégal - Cadre Régional Stratégiquede Gestion Environnementaleet Sociale 5.19 PROCEDURE DE « CHANCE-FIND » POUR IDENTIFIERLE PATRIMOINECULTUREL ..................................................... 37 6 CONSULTATION DES AUTORITES, DES ACTEURS ET DES POPULATIONS LORS DE LA CONDUITE DES ETUDES........ 38 LISTE DES ANNEXES - Annexe A: Liste des auteurs et contributions à l'étude - Annexe B: Listes des références bibliographiques et des personnes contactées - Annexe C: Comptes-rendus des réunions de consultation des populations, des consultations institutionnelles et des réunions de concertation - Annexe D: Tableaux et rapports annexes spécifiques - Annexe E: Liste des rapports associés ___ ( Page~~ 4 STUit SACi, Programme de Gestion Intégréedes Ressourcesen Eau et de Développementdes Usagesà Buts Multiples dans le Bassin du Fleuve Sénégal - Cadre RégionalStratégique de Gestion Environnementaleet Sociale Liste des tableaux et figures Liste des tableaux TABLEAU 1: OPERATIONS DE REBOISEMENTAU SENEGAL.................................................................................... -

Mli0006 Ref Region De Kayes A3 15092013

MALI - Région de Kayes: Carte de référence (Septembre 2013) Limite d'Etat Limite de Région MAURITANIE Gogui Sahel Limite de Cercle Diarrah Kremis Nioro Diaye Tougoune Yerere Kirane Coura Ranga Baniere Gory Kaniaga Limite de Commune Troungoumbe Koro GUIDIME Gavinane ! Karakoro Koussane NIORO Toya Guadiaba Diafounou Guedebine Diabigue .! Chef-lieu de Région Kadiel Diongaga ! Guetema Fanga Youri Marekhaffo YELIMANE Korera Kore ! Chef-lieu de Cercle Djelebou Konsiga Bema Diafounou Fassoudebe Soumpou Gory Simby CERCLES Sero Groumera Diamanou Sandare BAFOULABE Guidimakan Tafasirga Bangassi Marintoumania Tringa Dioumara Gory Koussata DIEMA Sony Gopela Lakamane Fegui Diangounte Goumera KAYES Somankidi Marena Camara DIEMA Kouniakary Diombougou ! Khouloum KENIEBA Kemene Dianguirde KOULIKORO Faleme KAYES Diakon Gomitradougou Tambo Same .!! Sansankide Colombine Dieoura Madiga Diomgoma Lambidou KITA Hawa Segala Sacko Dembaya Fatao NIORO Logo Sidibela Tomora Sefeto YELIMANE Diallan Nord Guemoukouraba Djougoun Cette carte a été réalisée selon le découpage Diamou Sadiola Kontela administratif du Mali à partir des données de la Dindenko Sefeto Direction Nationale des Collectivités Territoriales Ouest (DNCT) BAFOULABE Kourounnikoto CERCLE COMMUNE NOM CERCLE COMMUNE NOM ! BAFOULABE KITA BAFOULABE Bafoulabé BADIA Dafela Nom de la carte: Madina BAMAFELE Diokeli BENDOUGOUBA Bendougouba DIAKON Diakon BENKADI FOUNIA Founia Moriba MLI0006 REF REGION DE KAYES A3 15092013 DIALLAN Dialan BOUDOFO Boudofo Namala DIOKELI Diokeli BOUGARIBAYA Bougarybaya Date de création: -

D07 Fernandezalbo:Maquetación 1.Qxd

Pachjiri. Cerro sagrado del Titicaca Gerardo FERNÁNDEZ JUÁREZ Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha [email protected] Xavier ALBÓ CORRONS Centro de Investigación y Promoción del Campesinado CIPCA-La Paz [email protected] Recibido: 9 de noviembre de 2007 Aceptado: 15 de noviembre de 2007 RESUME El artículo describe las características etnográficas del cerro Pachjiri y de sus altares ceremoniales, que hacen de él un lugar sagrado para las comunidades aymaras próximas a las riberas del lago Titicaca. El cerro es sagrado en una doble vertiente, como centro de iniciación de los especialistas rituales aymaras (yatiris), y como lugar de peregrinación durante el mes de agosto, para el sacrificio de ofrendas en sus diferentes altares ceremoniales. Recientemente, los «hermanos evangélicos» aymaras han entrado en la disputa simbólica sobre este centro ceremonial, particularmente después de los rumores extendidos en el altiplano respecto del ofre- cimiento al cerro de un sacrifico humano. Palabras clave: Pachjiri, aymara, yatiri, Bolivia. Pachjiri. Sacred Mountain in the Titicaca ABSTRACT This paper describe the ethnographic characteristics of mountain called Pachjiri and his ceremonial altars, which make him a sacred place for the Aymara communities near to Titicaca lake. The mountain is sacred in a double sense: as center for the initiation of Aymara ritual specialists (yatiris), and as place of peregrination during August, for sacrificing offers in his different ritual altars. Recently, the Aymara «hermanos protestan- tes» (protestants believers) are started a symbolic fight on the ceremonial place, specially after the murmurs of a human sacrify to the mountain. Key words: Pachjiri, Aymara, yatiri, Bolivia. Sumario: 1. -

Phase II 2007 / 2009 – Région De Kayes - Mali

GRDR Groupe de recherche et de réalisations pour le développement rural Migration, citoyenneté et développement 66/72 rue Marceau 93109 Montreuil France Métro : Robespierre Tél. 01 48 57 75 80 Fax. 01 48 57 59 75 Email : [email protected] www.grdr.org 1901 oi l Association Appui aux Initiatives de Développement Local en Région de Kayes – Phase II 2007 / 2009 – Région de Kayes - Mali Janvier 2007 GRDR Mali BP. 291, Rue 136, porte n°37 – Légal Ségou face SEMOS – Kayes, Mali Tél. : (+) 223 252 29 82 et Fax : (+) 223 253 14 60 Courriel : [email protected] 1 SOMMAIRE I Synthèse du projet ____________________________________________________________ 5 1. Titre du projet __________________________________________________________________ 5 2. Localisation exacte_______________________________________________________________ 5 3. Calendrier prévisionnel___________________________________________________________ 5 4. Objet du projet _________________________________________________________________ 5 5. Moyens à mettre en œuvre ________________________________________________________ 7 6. Conditions de pérennisation de l’action après sa clôture________________________________ 7 7. Cohérence de l’action par rapport aux politiques nationales ____________________________ 7 8. Cohérence de l’action par rapport aux actions bilatérales françaises dans le pays __________ 8 II Présentation des partenaires locaux______________________________________________ 9 1. Assemblée Régionale de Kayes_____________________________________________________ 9 2. Association des -

University of Peloponnese Kurdish

University of Peloponnese Faculty of Social and Political Sciences Department of Political Studies and International Relations Master Program in «Mediterranean Studies» Kurdish women fighters of Rojava: The rugged pathway to bring liberation from mountains to women’s houses1. Zagoritou Aikaterini Corinth, January 2019 1 Reference in the institution of Rojava, Mala Jin (Women’s Houses) which are viewed as one of the most significant institutions in favour of women’s rights in local level. Πανεπιστήμιο Πελοποννήσου Σχολή Κοινωνικών και Πολιτικών Επιστημών Τμήμα Πολιτικής Επιστήμης και Διεθνών Σχέσεων Πρόγραμμα Μεταπτυχιακών Σπουδών «Μεσογειακές Σπουδές» Κούρδισσες γυναίκες μαχήτριες της Ροζάβα: Το δύσβατο μονοπάτι για την απελευθέρωση από τα βουνά στα σπίτια των γυναικών. 2 Ζαγορίτου Αικατερίνη Κόρινθος, Ιανουάριος 2019 2 Αναφορά στο θεσμό της Ροζάβα, Mala Jin (Σπίτια των Γυναικών) τα οποία θεωρούνται σαν ένας από τους σημαντικότερους θεσμούς υπέρ των δικαιωμάτων των γυναικών, σε τοπικό επίπεδο. Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my beloved brother, Christos, who left us too soon but he is always present to my thought and soul. Acknowledgments A number of people have supported me in the course of this dissertation, in various ways. First of all, I would like to express my sincere thanks to my supervisors, Vassiliki Lalagianni, professor and director of the Postgraduate Programme, Master of Arts (M.A.) in “Mediterranean Studies” at the University of Peloponnese and Marina Eleftheriadou, Professor at the aforementioned MA, for their assistance, useful instructions and comments. I also would like to express my deep gratitude to my family and my companion; especially to both my parents who have been all this time more than supportive. -

Voces Del Lago Primer Compendio De Tradiciones Orales Y Saberes Ancestrales

ESPAÑOL Voces del Lago Primer Compendio de Tradiciones Orales y Saberes Ancestrales COOPERACIÓN TÉCNICA BELGA (CTB): Edificio Fortaleza, Piso 17, Av. Arce N° 2799 Casilla 1286. La Paz-Bolivia Teléfono: T + 591 (2) 2 433373 - 2 430918 Fax: F + 591 (2) 2 435371 Email: [email protected] Titicaca Bolivia OFICINA DE ENLACE DEL PROYECTO DEL LAGO EN COPACABANA Proyecto de identificación, registro y revalorización del Dirección de Turismo y Arqueología, Proyecto del Lago Bolivia patrimonio cultural en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca, Bolivia Esq. Av. 6 de Agosto y 16 de Julio (Plaza Sucre) Voces del Lago Primer Compendio de Tradiciones Orales y Saberes Ancestrales “VOCES DEL LAGO” Es el Primer Compendio de Tradiciones Orales y Saberes Ancestrales de 13 GAMs. circundantes al Titicaca. Proyecto de Identificación, registro y revalorización del patrimonio cultural en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca, Bolivia. Wilma Alanoca Mamani Patrick Gaudissart Ministra de Culturas y Turismo Representante Residente CTB-Bolivia Leonor Cuevas Cécile Roux Directora de Patrimoino MDCyT Asistente Técnico CTB Proyecto del Lago José Luís Paz Jefe UDAM MDCyT Franz Laime Relacionador comunitario Denisse Rodas Proyecto del Lago Técnico UDAM MDCyT La serie Radial “Voces del Lago” (con 10 episodios, 5 en español y 5 en aymara) fue producida por los estudiantes y docentes de la UPEA que se detallan a continuación, en base a una alianza estratégica, sin costo para el Proyecto del Lago. La consultoría denominada: “Revalorización de la identidad cultural Estudiantes: comunitaria aymara a través de un mayor conocimiento de las culturas Abigail Mamani Mamani - Doña Maria ancestrales vinculadas al patrimonio arqueológico mediante concursos anuales Joaquin Argani Lima - Niño Carola Ayma Contreras – Relatora y publicaciones, con especial énfasis en las mujeres adultas mayores”, Nieves Vanessa Paxi Loza - Aymara fue realizada por: GERENSSA SRL. -

Universidad Nacional Mayor De San Marcos La

Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Universidad del Perú. Decana de América Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Escuela Profesional de Antropología La ambivalente conceptualización antropológica sobre el indio en el Perú. De la convergencia indigenista a la antropología en el Cusco (1909-1973) TESIS Para optar el Título Profesional de Licenciado en Antropología AUTOR César AGUILAR LEÓN ASESOR Mg. Harold Guido HERNÁNDEZ LEFRANC Lima, Perú 2019 Reconocimiento - No Comercial - Compartir Igual - Sin restricciones adicionales https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Usted puede distribuir, remezclar, retocar, y crear a partir del documento original de modo no comercial, siempre y cuando se dé crédito al autor del documento y se licencien las nuevas creaciones bajo las mismas condiciones. No se permite aplicar términos legales o medidas tecnológicas que restrinjan legalmente a otros a hacer cualquier cosa que permita esta licencia. Referencia bibliográfica Aguilar, C. (2019). La ambivalente conceptualización antropológica sobre el indio en el Perú. De la convergencia indigenista a la antropología en el Cusco (1909- 1973). [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Escuela Profesional de Antropología]. Repositorio institucional Cybertesis UNMSM. Hoja de metadatos complementarios Código ORCID del autor https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8991-9317 DNI o pasaporte del autor 73360609 Código ORCID del asesor https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4912-5931 DNI o pasaporte del asesor 08736452 Grupo de investigación — Agencia financiadora — Cusco 13° 30' 45" latitud Sur y a 71° 58' 33" Ubicación geográfica donde se longitud Oeste desarrolló la investigación Año o rango de años en que 1942-1973 se realizó la investigación Humanidades y ciencias jurídicas y sociales: 1.- Antropología http://purl.org/pe-repo/ocde/ford#5.04.03 Disciplinas OCDE 2.- Sociología http://purl.org/pe-repo/ocde/ford#5.04.01 3.- Etnología http://purl.org/pe- repo/ocde/ford#5.04.04 ÍNDICE Introducción 3 Primera parte.